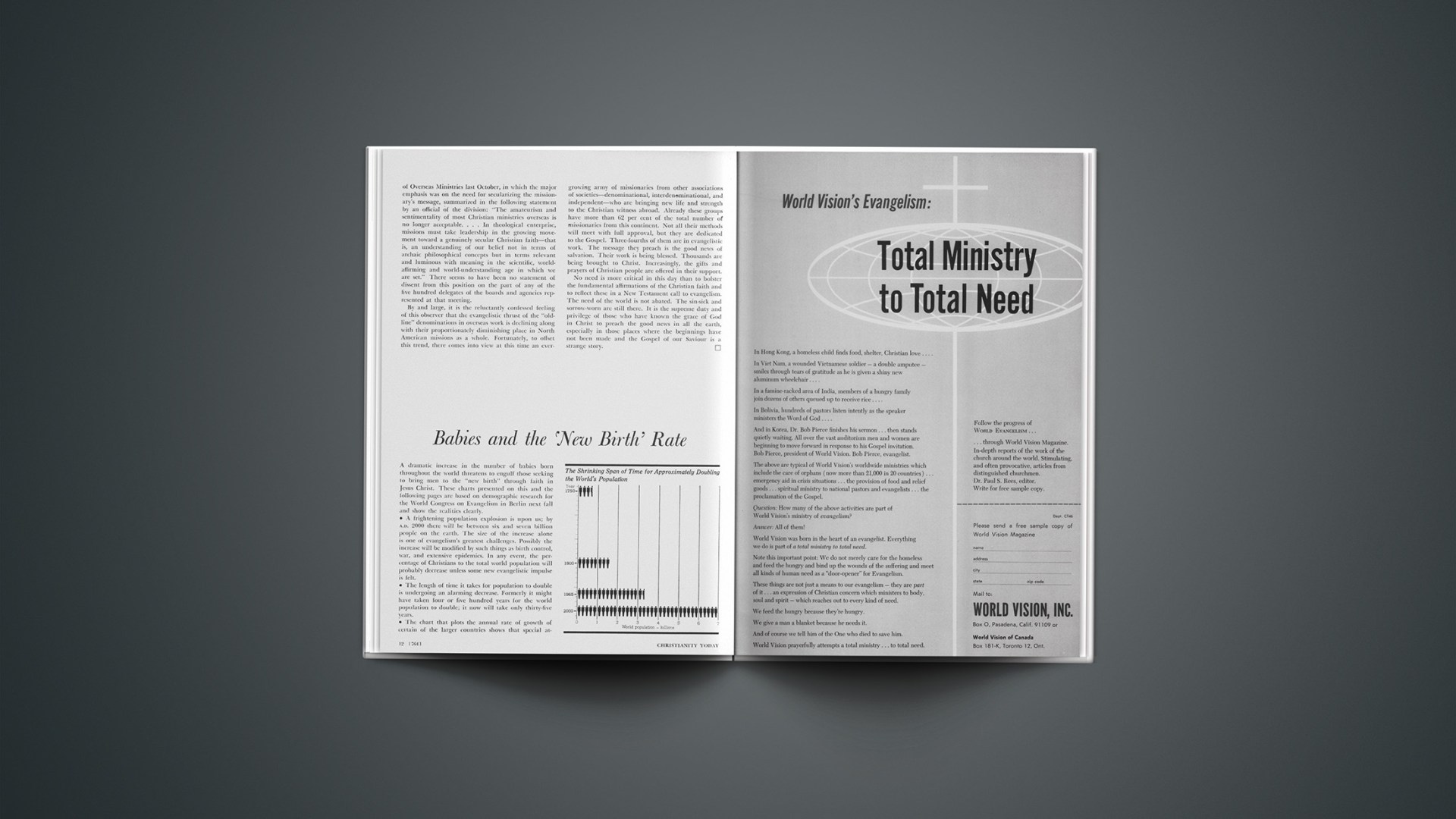

A dramatic increase in the number of babies born throughout the world threatens to engulf those seeking to bring men to the “new birth” through faith in Jesus Christ. These charts presented on this and the following pages are based on demographic research for the World Congress on Evangelism in Berlin next fall and show the realities clearly.

• A frightening population explosion is upon us; by A.D. 2000 there will be between six and seven billion people on the earth. The size of the increase alone is one of evangelism’s greatest challenges. Possibly the increase will be modified by such things as birth control, war, and extensive epidemics. In any event, the percentage of Christians to the total world population will probably decrease unless some new evangelistic impulse is felt.

• The length of time it takes for population to double is undergoing an alarming decrease. Formerly it might have taken four or five hundred years for the world population to double; it now will take only thirty-five years.

• The chart that plots the annual rate of growth of certain of the larger countries shows that special attention must be given to Mexico, Brazil, Turkey, South Africa, Indonesia, and the Congo, for their populations will double in less than thirty-five years. Of the world’s larger nations, only Japan has a rate of growth significantly lower than the average.

• While there is one missionary for slightly more than 70,000 people, the distribution of the total force is very uneven; there are no missionaries in China, for instance, with its more than 700 million people. The slackening of missionary enthusiasm in the sending countries and the scarcity of candidates suggests that the next missionary wave must come from within the younger churches, with nationals reaching their own people with the Gospel.

• The missionary force has increased faster than the populations have, but not fast enough to fulfill the Great Commission. Significantly, North America has become the key sending base, and this situation is likely to continue indefinitely.

• In the last hundred years, the number of non-Christians in the world has more than doubled. Although Protestants in growth have more than kept pace with population, they are still a small minority of the world’s population.

• Christians in the United States face a great evangelistic opportunity, since the country will have approximately 150 million more people by A.D. 2000. However, the rate of growth for 1965 was the lowest since World War II (1.2 per cent); and since the United States is among those nations most inclined toward birth control, the net increase of population by A.D. 2000 may be smaller than the estimate based on recent birth figures.

Data for the charts came from the following sources:

1. Population Reference Bureau, Incorporated, Washington, D.C.

2. Interpretative Statistical Survey of the World Mission of the Christian Church, edited by Joseph I. Parker, New York and London, 1938.

3. The Christian Yearbook, London, 1868.

4. Britannica Book of the Year, 1964.

5. Demographic Yearbook of the United Nations.

6. National Geographic Society.

7. Missionary Research Library and Dr. Herbert Jackson, director.

8. Dr. Kenneth Scott Latourette, Sterling Professor Emeritus of Missions and Oriental History, Yale University.