A daring gesture of ecumenical initiative came this month in an announcement from Lambeth Palace:

Dr. Geoffrey Francis Fisher, titular head of the world Anglican communion, had succeeded in arranging an early December audience with Pope John XXIII.

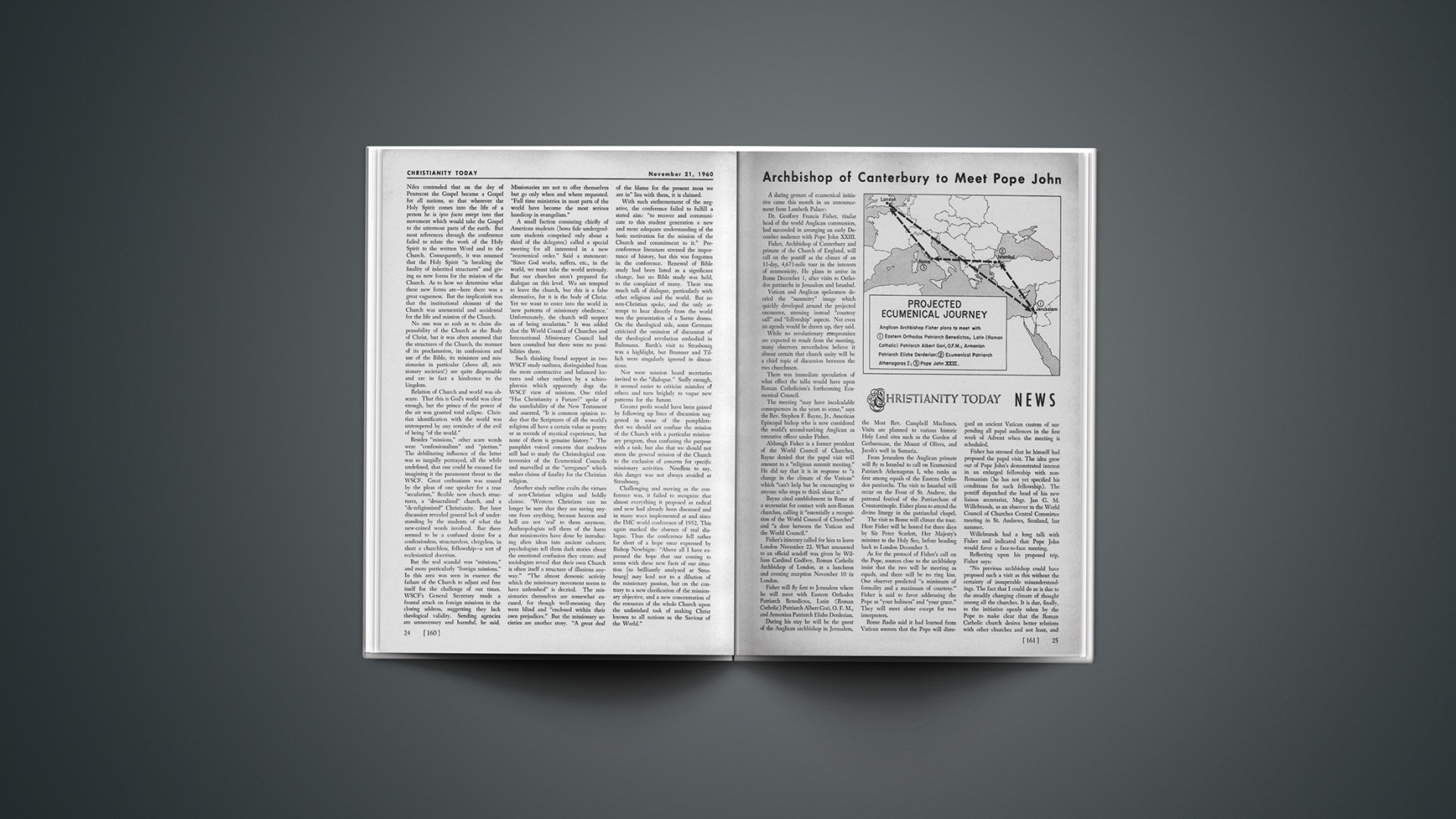

Fisher, Archbishop of Canterbury and primate of the Church of England, will call on the pontiff as the climax of an 11-day, 4,671-mile tour in the interests of ecumenicity. He plans to arrive in Rome December 1, after visits to Orthodox patriarchs in Jerusalem and Istanbul.

Vatican and Anglican spokesmen decried the “summitry” image which quickly developed around the projected encounter, stressing instead “courtesy call” and “fellowship” aspects. Not even an agenda would be drawn up, they said.

While no revolutionary compromises are expected to result from the meeting, many observers nevertheless believe it almost certain that church unity will be a chief topic of discussion between the two churchmen.

There was immediate speculation of what effect the talks would have upon Roman Catholicism’s forthcoming Ecumenical Council.

The meeting “may have incalculable consequences in the years to come,” says the Rev. Stephen F. Bayne, Jr., American Episcopal bishop who is now considered the world’s second-ranking Anglican as executive officer under Fisher.

Although Fisher is a former president of the World Council of Churches, Bayne denied that the papal visit will amount to a “religious summit meeting.” He did say that it is in response to “a change in the climate of the Vatican” which “can’t help but be encouraging to anyone who stops to think about it.”

Bayne cited establishment in Rome of a secretariat for contact with non-Roman churches, calling it “essentially a recognition of the World Council of Churches” and “a door between the Vatican and the World Council.”

Fisher’s itinerary called for him to leave London November 22. What amounted to an official sendoff was given by William Cardinal Godfrey, Roman Catholic Archbishop of London, at a luncheon and evening reception November 10 in London.

Fisher will fly first to Jerusalem where he will meet with Eastern Orthodox Patriarch Benedictos, Latin (Roman Catholic) Patriarch Albert Gori, O. F. M., and Armenian Patriarch Elishe Derderian.

During his stay he will be the guest of the Anglican archbishop in Jerusalem, the Most Rev. Campbell Maclnnes. Visits are planned to various historic Holy Land sites such as the Garden of Gethsemane, the Mount of Olives, and Jacob’s well in Samaria.

From Jerusalem the Anglican primate will fly to Istanbul to call on Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras I, who ranks as first among equals of the Eastern Orthodox patriarchs. The visit to Istanbul will occur on the Feast of St. Andrew, the patronal festival of the Patriarchate of Constantinople. Fisher plans to attend the divine liturgy in the patriarchal chapel.

The visit to Rome will climax the tour. Here Fisher will be hosted for three days by Sir Peter Scarlett, Her Majesty’s minister to the Holy See, before heading back to London December 3.

As for the protocol of Fisher’s call on the Pope, sources close to the archbishop insist that the two will be meeting as equals, and there will be no ring kiss. One observer predicted “a minimum of formality and a maximum of courtesy.” Fisher is said to favor addressing the Pope as “your holiness” and “your grace.” They will meet alone except for two interpreters.

Rome Radio said it had learned from Vatican sources that the Pope will disregard an ancient Vatican custom of suspending all papal audiences in the first week of Advent when the meeting is scheduled.

Fisher has stressed that he himself had proposed the papal visit. The idea grew out of Pope John’s demonstrated interest in an enlarged fellowship with non-Romanists (he has not yet specified his conditions for such fellowship). The pontiff dispatched the head of his new liaison secretariat, Msgr. Jan G. M. Willebrands, as an observer to the World Council of Churches Central Committee meeting in St. Andrews, Scotland, last summer.

Willebrands had a long talk with Fisher and indicated that Pope John would favor a face-to-face meeting.

Reflecting upon his proposed trip, Fisher says:

“No previous archbishop could have proposed such a visit as this without the certainty of insuperable misunderstandings. The fact that I could do so is due to the steadily changing climate of thought among all the churches. It is due, finally, to the initiative openly taken by the Pope to make clear that the Roman Catholic church desires better relations with other churches and not least, and expressly, with the Church of England and its sister churches.”

“… What my proposed visit to the Pope has established, I hope, is that in the future Anglicans, Roman Catholics and others can talk together freely and openly in a spirit of Christian friendship and fellowship, not seeking victory over one another but as fellow disciples in the service of one Lord—learning as Christians always must learn, first by talking with one another and speaking the truth as they see it in love.”

The Ecumenist

Dr. Geoffrey Francis Fisher, 73, has been Archbishop of Canterbury since 1945. Prior to his elevation to the highest Anglican office he served as a bishop in London and Chester and, for 18 years, as headmaster of a school. He has never held a parish.

Fisher was the tenth child of the rector of Higham-on-the-Hill, Nuneaton. He attended school at Marlborough, then won a scholarship to Exeter College, Oxford, where he took both academic and athletic honors.

He studied for a short time at Wells Theological College and returned to his old school, Marlborough, as an assistant master. He was only 27 when he succeeded William Temple as headmaster of Repton. Temple later became Archbishop of Canterbury and Fisher succeeded him to that office as well.

Fisher’s first public statement after becoming archbishop was an appeal for ending of color bars throughout the British Commonwealth. He has been regarded as an outspoken churchman ever since.

Early this month he openly reprimanded Dr. John Arthur Thomas Robinson, Anglican Bishop of Woolwich, who had testified at a trial in defense of the publishers of Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Robinson told the court he thought author D. H. Lawrence had tried to portray sex relations as something sacred and in a real sense as an act of holy communion. He said Christians ought to read the book.

Fisher, addressing the Canterbury Diocesan Conference, said Robinson had a full right to appear as a witness on a point of law, but to do so was obviously bound “to cause confusion in many people’s minds between his individual right of judgment and the discharge of his pastoral duties.”

The trial ended with the jury ruling that the novel was not obscene.

A public rebuke of this kind is very rare in the Church of England. In 1927, Dr. Ernest William Barnes, the then Bishop of Birmingham, was rebuked by Dr. Randall T. Davidson, then Archbishop of Canterbury, for views publicly voiced, particularly on sacramental doctrine.

Fisher is the 100th head of an archdiocese that was formerly Roman Catholic, but for 400 years has been the primatial see of the Anglican community.

Canterbury To Rome: The Visit In Perspective

The news that Dr. Geoffrey Fisher, Archbishop of Canterbury, is to visit the Pope in Rome next month has occasioned widespread comment. On the whole the reaction has been one of restrained approval. It is felt that in our world as it is today the opening of doors of communication can only be a good thing, provided there is no compromise on matters of principle. The projected visit seems to be an outcome of the interest which the Roman Catholic church is now beginning to show in the ecumenical movement. This in itself is a new factor and cannot fail to be creative in some measure of a new situation. Thus two Roman Catholic observers were present at the meeting of the Central Committee of the World Council of Churches held in St. Andrews, Scotland, in August, and one of them. Monsignor Willebrands, has been appointed head of the new secretariat for Christian unity which Pope John has set up.

It has been emphasized that this will be no more than a courtesy visit and that there will be no agenda of things to be discussed. To imagine that it can be limited to an act of courtesy is, however, somewhat naive. “The visit cannot be treated merely as an act of courtesy,” comments the London Daily Telegraph. “It marks, in fact, an awareness in both communions, sharpened no doubt by the increased power of the anti-Christian Communist philosophy, that disunity among Christians is too great a scandal to be ignored and too serious a weakness to be left unremedied.”

An editorial in the Church of England Newspaper (published weekly in London) is to the point. “It is not inopportune for members of the Church of England to remind themselves,” it says, “that the position of the Church of England vis-à-vis the Roman Catholic Church is clearly defined in the Thirty-nine Articles.… The Archbishop of Canterbury—and here we speak, we trust, with entire courtesy—will stand before the Pope as representing a Church which says quite clearly: ‘As the Church of Jerusalem, Alexandria, and Antioch have erred; so also the Church of Rome hath erred, not only in their living and manner of ceremonies, but also in matters of Faith.’ ” This will be the first time that an Archbishop of Canterbury has visited the Pope since before the Reformation. Thomas Cranmer, however, did journey to Rome and met the Pope in 1530—two years before he became Archbishop of Canterbury. The occasion was a deputation, led by the Earl of Wiltshire, in connection with the matter of the King of England’s divorce. Foxe describes how, when the Pope preferred his toe to be kissed, members of the delegation maintained an unbending dignity and refused to engage in any such act of obeisance. The Earl of Wiltshire’s spaniel, however, unaffected by inhibitions of this kind, moved forward and seized the sacred toe with his teeth, whereupon his holiness hastily withdrew it under the shelter of his robes. Beyond all doubt the present Archbishop of Canterbury will observe a like gravity and refrain from any act of obeisance to the Roman pontiff—though it is not suggested that he should take a spaniel dog along with him!

P.E.H.

The Last Enemy

Death has taken several well-known religious figures in recent weeks.

Dr. Donald Grey Barnhouse, noted Bible expositor and editor-in-chief of Eternity magazine, died November 4 in Philadelphia. He had been confined to Temple University Hospital for a month following surgery for a malignant brain tumor.

Barnhouse, 65, was minister of the Tenth Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia for the last 33 years. His radio voice was known to millions.

Associates say adjustments will be made to enable the Barnhouse ministries to continue. His “Bible Study Hour,” heard over the National Broadcasting Company network, is recorded through next Easter.

Barnhouse’s death in Philadelphia preceded by a day a private funeral service in the same city for another noted evangelical personality.

Dr. Percy B. Crawford, television-radio evangelist and Christian youth leader, died of a heart ailment October 31 in a Trenton, New Jersey, hospital.

The 58-year-old Crawford was taken to the hospital two days earlier when he collapsed at a roadside restaurant while en route to a church speaking engagement. He had suffered six previous heart attacks in the last two years.

The day following the private funeral service, a public memorial service was conducted by evangelist Billy Graham in Philadelphia’s Town Hall. Crawford is survived by his wife, four sons aged 16 to 24, and a daughter, 11.

He was founder-president of King’s College and originator of the “Young People’s Church of the Air” radio broadcast and the “Youth on the March” telecast. His organization recently began operation of a television channel of its own in Philadelphia. He also operated summer camps in the Pennsylvania Poconos. Attempts will be made to carry on many of these enterprises.

Dr. Halford E. Luccock, 75, died November 5 in New Haven, Connecticut, after a short illness.

Luccock, professor emeritus of preaching at Yale Divinity School, had written, under the pseudonym of Simeon Stylites, a column for The Christian Century since 1948.

The son of a Methodist bishop, Luccock was ordained into the Methodist Episcopal ministry in 1910.

He was the author of some 25 books, mostly about religion and literature. He taught at Yale for 25 years, retiring in 1953. He had lived in Connecticut.

John James Allan, top-ranking Salvation Army leader and a founder of United Service Organizations (better known to U. S. servicemen as the USO), died October 31 in Clearwater, Florida, at the age of 73.

Allan helped found the USO in 1940 while serving as assistant chief of chaplains in the U. S. Army. In 1946 he went to the international headquarters of the Salvation Army in London. He was the highest U. S.-born Salvation Army officer in the organization’s history.

Membership Loss

The Evangelical United Brethren denomination recorded a net loss of 1,522 members during the last year, according to newly-released figures from the church’s international headquarters in Dayton, Ohio.

Current membership in 4,418 organized congregations in the United States was given as 761,858.

Dr. Paul W. Milhouse, church statistician, attributed the loss chiefly to the mass movement of the population toward metropolitan centers. The EUB church has historically stressed a ministry to rural areas and small towns.

The membership loss is the first since 1946 when a union was consummated between the Evangelical Church and the Church of the United Brethren in Christ.

POAU on Kennedy

President-elect Kennedy can count on the “strong support” of Protestants and Other Americans United in his support of Church-State separation.

“Although Kennedy’s position is not that of the bishops of his church,” says Glenn L. Archer, POAU executive director, “we believe that the majority of the Catholic people of the United States agree with him, and we look forward to an administration in which the new president will faithfully adhere to the pledge of Church-State separation which he gave so solemnly. We hope to provide strong support for Mr. Kennedy in his endeavors to support this principle.”

Needed: Higher Incentive

Despite the incentive of a 30 per cent deduction allowable against taxable income, Americans channel relatively little of their ample means toward religious, educational, and social welfare activities.

Only 1.36 per cent of all personal consumption expenditures fell into the “religious and welfare activities” category last year, according to the U. S. Department of Commerce. The department arrives at the “religious and welfare activities” figure by totalling operating expenses, including depreciation, of all religious and social welfare (ex. Red Cross, Community Chest) organizations.

Protestant Panorama

• Witness, service, and unity will be sub-themes of the Third World Council of Churches Assembly in New Delhi, India, next fall. Main theme is “Jesus Christ—the Light of the World.” Some 1,000 church and lay leaders will participate. About two-thirds this number will be official delegates of member churches.

• The Presbytery of Tasmania will ask its General Assembly to endorse state aid to church schools. An article in the presbytery’s journal, Presbyterian Life, stresses that such assistance must take the “form of capital grants, administered by a formula that would preclude disproportionate aid to any denomination and allow no measure of state control.”

• Testimony began in a New York federal court this month in a suit to block merger of the Congregational Christian Churches’ General Council and the Evangelical and Reformed Church. Seeking to nullify the “basis of union” for the new United Church of Christ are four Congregational churches and 10 individuals.

• Dr. J. W. W. Shuler, 100-year-old Methodist minister, marked the start of his second century by preaching a sermon at the First Methodist Church in Hillsboro, Texas. Shuler, who came to Texas from the East almost 50 years ago in search of drier climate for his health, still preaches regularly, does 17 rounds of calisthenics every morning, eats heartily, and works his own garden.

• Southern Presbyterians are redesigning their Christian education program. A new “Covenant Life Curriculum” to be ready for use in the fall of 1964 is aimed at eventually replacing the “Uniform Lessons” and “Graded Materials” series.

• Church of the Nazarene congregations are conducting a “Try Christ’s Way” crusade this month. Evangelism secretary Edward Lawlor says the crusade (“most intensive effort to reach people on a denominational scale in the history of our church”) calls upon each member to establish a witness with seven people and to invite each to attend church.

• Whereas 35 years ago Christian thought was most seriously challenged by the natural sciences, the crucial problem today is philosophy, according to Dr. J. Oliver Buswell, Jr., president of Covenant Seminary, who addressed the seventh annual philosophy conference at Wheaton College this month.

• Anglicans consecrated their first native-born bishop in the Pacific Islands last month. He is the Rev. George Ambo, 37, born in New Guinea and educated in mission schools. At consecration ceremonies in a Brisbane, Australia, cathedral, Ambo was made assistant bishop of New Guinea.

• Fire destroyed a men’s dormitory at Clarke Memorial College, a Baptist school in Newton, Mississippi, this month. About half the students lost all their clothing, but none were seriously injured.

• The Accrediting Association of Bible Colleges admitted three new associate members at an annual meeting in Chicago last month: Atlanta (Georgia) Christian College; Appalachian Bible Institute, Bradley, West Virginia; and Canadian Bible College, Regina, Saskatchewan.

• The Holy Ghost Church of Dalby, Sweden, oldest stone house of worship in Scandinavia, was rededicated last month after a thorough renovation. Although its exact age is not known, the church is mentioned in a document as early as 1060.

• The Hymn Society of America is sponsoring a contest for compositions which have as their theme aspects of Christian marriage and family life. The contest is open to all composers and musicians in the United States and Canada. Deadline for submission is February 15, 1961.

• It took the state court of appeals to settle a dispute over use of instrumental music in the Church of Christ at Virgie, Kentucky. The court ruled that a group in the church which favored the music was the majority group and was entitled to exclusive use of the church property.

Monkey Tricks

From the opening moments, when a contralto voice is heard singing repeatedly “Give me the old-time religion; it’s good enough for me,” the United Artists film “Inherit the Wind,” purporting to reproduce the Scopes “monkey” trial of 1925, is drastically loaded against the Christian religion. A more deplorable caricature of sacred things would be difficult to imagine: an unloving and unlovable cleric savagely and publicly consigning his only daughter to the direst torments of hell because of her unwillingness to renounce her love for the young schoolteacher who has been put on trial for teaching Darwinism in the classroom; the jaunty irreverence of Gene Kelly acting the part of famed reporter H. L. Mencken of the Baltimore Sun; the portrayal by Frederic March of William Jennings Bryan, counsel for the prosecution, as a stupid, gluttonous egotist; and the chunky performance of Spencer Tracy as Clarence Darrow, counsel for the defense, who is made the real hero of the film and steals its thunder—all these (the names of the actual persons involved in 1925 are changed), together with the oppressive blanket of hysterical obscurantism in which it is wrapped up and handed to the public, combine to make this a film which will do more to travesty the Christian faith than a hundred books advocating atheism.

The film is now playing in theaters across the United States.

Stanley Kramer produced and directed the film from the popular stage drama by Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee.

All that remains to be said is that if the moronic mob depicted on the screen is typical of American small town citizenry, and if the Tracy-March duo are supposed to reproduce the rhetorical heights of American advocacy, heaven preserve us. Bathos pervades the whole, not least when, with studied symbolism, Tracy leaves the deserted courtroom with two books—Darwin and the Bible—under his arm, after he has shed gallons of perspiration in an attempt to prove that the one is incompatible with the other. It may be as well to remember that there are scientists as well as Christians who repudiate Darwinism, and that obscurantism, so far from being the preserve of particular religious pockets, is not unknown in scientific circles. Because of its double-thickness bias this film inverts and drapes itself with the obscurantism which it is intent on exposing, and merits an “oscar” for its services in the noble cause of prejudice.

P.E.H.

30-Year Ordeal

Mrs. Katherine Voronaeff, 73-year-old wife of a Russian-born Assemblies of God missionary, is now living in the United States after spending most of the last 30 years in Soviet prisons. Whereabouts of the husband, the Rev. John E. Voronaeff, also a victim of Communist imprisonment, are unknown.

Mrs. Voronaeff was freed from prison in 1953, but it took seven more years of negotiations between the Kremlin and the U. S. State Department to enable her to join her six children in America. She expects to spend the next several months with a son in Los Angeles.

Both Mr. and Mrs. Voronaeff were born in Russia, but emigrated to the United States in their youth and even took out citizenship papers. In the interests of evangelizing their own people, however, the couple went back under sponsorship of the Assemblies of God Foreign Missions Department. Voronaeff became chairman of the denomination’s work in Russia and experienced a fruitful ministry. The work came to a sudden halt when, on a cold winter night in 1930, 800 pastors were rounded up, imprisoned and subsequently shipped to Siberia.

For three years Mrs. Voronaeff tried secretly to carry on her husband’s work. Then she, too, was arrested and placed in prison.

When the couple was released in 1940, the Assemblies of God raised funds for their return to the United States. But when the pastor approached the Soviet government to sign the necessary papers, he was re-arrested and returned to Siberia. He has not been heard from since.

Clergy Strain

Clergymen are more prone to emotional stress and strain than laymen, according to an exhaustive study made at Baptist Hospital in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

The study shows ministers to have a significantly higher incidence of diseases where emotional factors are known to be important.

In a comparison of case histories of 1,000 ministers who have been patients at the hospital, 20 per cent gave evidence of relationship between vocation and illness. Ministers were found to be more susceptible to illness between the ages of 30 and 40.

The study was compiled by Dr. Albert L. Meiburg, director of research for the hospital’s department of pastoral care, in collaboration with Dr. Richard K. Young, head of the department.

Auca Film

Selected evangelical groups are previewing a 35-minute sound film which traces attempts to bring the Gospel to Ecuador’s savage Auca Indians.

Included are sequences taken during the period when five young missionaries were killed by the Aucas nearly five years ago.

Mrs. Elisabeth Elliot, one of the five widows of the slayings, narrates the film. The film is said to have been produced under her direction. She is now back in South America. No distributor has been named.

Tokyo Crusade

Dr. Oswald J. Smith, founder of Toronto’s People Church, conducted a week-long evangelistic campaign in Tokyo last month.

A spokesman for Smith said the meetings, held under the auspices of nearly 100 evangelical churches and pastors, represented the first united evangelistic campaign ever held in the world’s largest city.

The 2,200-seat Kyoritz Hall proved inadequate for the large crowds. A total of 796 made first-time professions of salvation. They were counselled by some 400 Navigators-trained nationals.

A large choir and a Salvation Anny band provided music for the services.

The Kyoritz Hall meetings were held in the evening. In addition, afternoon services were conducted in a Salvation Army hall.

Yoji Iwashiga was Smith’s interpreter for the crusade. All expenses were met by Japanese churches.

Evangelism in Brussels

By November 6, when the climactic closing service drew an overflow crowd of 2,500 to Brussels’ famed Albert Hall, it was clear that British Evangelist Eric Hutchings’ 23-day crusade had written a new chapter in the history of Belgian Protestantism.

Total impact warmed the hearts of Belgian Protestants, who make up scarcely one per cent of the population.

An aggregate of some 25,000 attended crusade meetings.

Reported Le Soir, Brussels largest daily, “It is the first time in the history of Protestantism in Brussels that meetings have been organized on such a scale.”

Sixteen ministers representing eight Protestant denominations sponsored the visit of Hutchings, who some years ago gave up a law practice to preach.

At each service the evangelist asked members of the audience to step forward to indicate new faith in Christ. A total of about 400 responded.

“Not since Reformation days,” said one observer, “had Brussels seen so many at the altar rail.”

A 175-member choir sang nightly. Hutchings’ sermons were interpreted into Flemish, German, and Russian via earphones.

The Rev. Walter W. Marichal, president of the Brussels Ministerial Association, served as crusade chairman.

Missions Vacancies

The Southern Baptist Home Mission Board says it has an immediate, urgent need for 270 personnel.

“There are mission centers which cannot be opened until missionaries are provided,” stated Glendon McCullough, personnel secretary for the board. “We have vacancies in Spanish work that have not been filled in two years because there are no qualified mission applicants.”

Petition Denial

The U. S. Supreme Court denied without an opinion last month a petition from the Russian Orthodox Greek Catholic Church of America for a rehearing on the question of ownership of St. Nicholas Orthodox Cathedral, New York.

Control of the cathedral, in dispute since 1924, was given to the Patriarchal Russian Orthodox Church in the United States by the Supreme Court last June in an unanimous opinion.

At that time the court held that Archbishop Boris, appointee of the Moscow Patriarchate as head of the Patriarchal Church in this country, and his supporters have the right to possession and control of the cathedral.

The controversy over which faction owned the edifice started 36 years ago when a large majority of clergy and faithful of the Russian Orthodox Church in this country established the autonomous body on the ground that the Moscow Patriarchate had become a tool of an atheist state.

The Supreme Court also refused to review a decision by a Cleveland federal court which rejected a claim by Bishop Andrei Moldovan that he is head of the Romanian Orthodox Episcopate in America.

Once before in 1954 the high tribunal rejected his appeal from a permanent injunction issued by the federal court forbidding him to represent himself as head of the denomination in this country.

Bishop Moldovan flew secretly to Romania in 1950 where he was consecrated Bishop of the Romanian Orthodox Episcopate of America by the Holy Synod in Bucharest. This action was not recognized by most of the Romanian churches in America which charged that Romanian Communists planned to use their new bishop as a tool in this country.

Subsequently the anti-Moldovan forces elected Bishop Valerian D. Trifa as head of the episcopate which has its headquarters in Jackson, Mich. The episcopate has no canonical ties with the Orthodox Church in Romania.

Catholic Newsmen

A school of journalism for the training of Roman Catholic newspapermen was formally inaugurated in Madrid, Spain, last month by Bishop Pedro Cantero Cuadrado of Huelva. Enrolled for the initial courses were 53 men and 13 women, all university graduates.

The bishop said that the function of the Catholic press was not merely to deal with “confessional subjects, religious art, et cetera” but with everyday themes and problems, giving them a “Christian orientation.”

Pacifist Play

A pacifist-motivated play, which deals with “alternatives to war” through modern drama techniques, and has as its “angel” the American Friends Service Committee, is on a 7,000-mile tour of 30 cities.

It is a followup to a more limited tour last spring which brought favorable audience response and reviews, according to Religious News Service.

The play, “Which Way the Wind,” was written by Philip C. Lewis and adapted to a technique he calls Docu-Drama.

Many of the performances will be in church auditoriums.

Congo Appeal

The World Council of Churches is appealing for $1,000,000 for projects to aid the troubled Congo.

Endorsed this month by the administrative committee of the WCC’s Division of Inter-church Aid and Service to Refugees was an appeal to churches for a broad program of aid ranging from immediate relief to the establishment of secondary school training.

The WCC is also issuing an appeal for East Pakistan where some 6,000 persons died in a recent cyclone.

The WCC refugee committee, which met in Buck Hill Falls, Pennsylvania, also heard a report that churches have contributed $340,361 in cash for victims of earthquakes in Chile. Of this amount, $238,000 came from German churches.

People: Words And Events

Deaths: See “The Last Enemy,” page 27.

Appointments: As president of Phillips University, Dr. Hallie Gantz … as professor of homiletics at Union Theological Seminary, New York, Dr. Edmund A. Steimle … as director of Seamen’s Church Institute, New York, the Rev. John M. Mulligan … as executive secretary of the World Council of Churches Youth Department, the Rev. Roderick S. French.

Elections: As president of the Baptist Theological Seminary in Ruschlikon, Switzerland, Dr. J. D. Hughey, Jr. … as chairman of the Methodist Board of Publication, F. Murray Benson … as warden of the College of Preachers of Washington Cathedral, the Rev. Frederick H. Arterton … as moderator of the National Association of Congregational Christian Churches, Dr. Max Strang … as chairman of the Christian Business Men’s Committee, International, Alfred R. Jackson … as president of the Presbyterian Men’s Council, Vernol R. Janson … as president of the Christian Writers Association of Canada, the Rev. B. T. Parkinson.

Nomination: As moderator-designate of the Church of Scotland General Assembly, Dr. A. C. Craig.

Consecration: As Anglican Bishop of Auckland, New Zealand, Dr. Eric A. Gowing.