Some five years ago theologians were introduced to a new definition for a host of world-influencing sects, cults, and small church movements. The definition, “Third Force in Christendom,” was coined for a 20-million-strong group by Dr. Henry Pitney Van Dusen, president of Union Theological Seminary. Since that time theologians, scholars, and writers by the dozen have recognized the influence of the “force,” some with disdain, others with question. None has attempted to explain it and few have speculated on its future. In fact, no one has separated the varied and in many cases diametrically-opposed segments into like parts, theologically speaking. The original grouping was correct only in terms of relatively recent historic origin, evangelistic zeal and socio-cultural appeal. To illustrate, the theological beliefs of the 17 churches mentioned in a Life Magazine article in June, 1958, vary all the way from the deviant position of the cult to beliefs closely resembling those held by the historic Christian churches.

Basically the 17 churches can be grouped in three bodies: (1) Holiness churches associated with the National Holiness Association; (2) Pentecostal churches holding membership in the Pentecostal Fellowship of North America; and (3) “Others,” a segment independent of any association and varying widely, in some cases even bordering on the status of cults. Churches found in the first two divisions are strongly represented in the National Association of Evangelicals. Seven out of 13 denominations, comprising a large percentage of the churches, have clearly cast their lot with the evangelical side of Christendom in contradistinction to ecumenical inclusivism.

UNTOUCHED STRATA

How these groups originated, their past growth, and prospect in the future, have attracted the attention of both the conservative and liberal forces in Christendom. Many of the churches have reached social strata of the world’s population never touched by other forces in Christendom, and are now touching people sometimes “assigned” to the historic church. While some in the past have thought of these groups as cults, or at best sects on the fringe of the historic, the churches on Main Street (the “first” and “second” forces) are now having to move over to make room for the sociological, educational, and economic advance of the “third force.”

Some may still be classed as sects so far as their theological pattern is concerned. Such categorizing is not necessarily to be interpreted as being derogatory. The late Dr. William Warren Sweet, dean of American church historians, once pointed out that “in the minds of many people the term sect implies an ignorant, over-emotionalized, and fanatical group; an ephemeral, fly-by-night movement that is here today and gone tomorrow.” This all-too-often accepted position, he explained, cannot be applied to many churches found in what Dr. Van Dusen calls the “third force.”

Dr. Sweet’s “rule of thumb” for distinguishing a sect from a church or cult may partially explain the astonishing growth of the “third force.” Here are his criteria for categorizing some churches as sects: “(1) They reject the “State Church” principle, (2) they oppose creeds and confessions of faith, (3) they reject infant baptism, (4) they accept religion as a way of life (exclusive of membership), and (5) they follow a simple polity.” As opposed to this standard, he defines a church as an organized body which accepts “(1) creed or confession of faith, (2) infant baptism and automatic membership, and (3) an elaborate church polity.”

The word “cult” has often been used as a label for any group which does not follow historic thinking in religion, but Dr. Sweet disagrees. He classifies a cult as a religious group which looks for its basic authority outside Christian tradition. “Generally cults accept Christianity, but only as a halfway station on the road to greater ‘truth,’ and profess to have a new and additional authority beyond Christianity,” Dr. Sweet wrote. As examples of cults he suggests the Latter-Day Saints who stress the Book of Mormon, and Christian Scientists whose beliefs center on Science and Health.

Most of the “third force” falls into the sect classification, we judge by Dr. Sweet’s standard. One or two groups would be on edge of becoming churches, while two or three might be typed as cults or near-cults. Such organizations as the Christian and Missionary Alliance, Pentecostal Holiness, and similar groups he would call sects. The Church of the Nazarene, Dr. Sweet suggests, is an example of a body changing from sect to church status. Many Baptist groups have moved or are moving into the church category. The Jehovah’s Witnesses might be classed as a cult—certainly they are commonly recognized as such by evangelicals.

Of the 17 organizations mentioned in the Life Magazine article by Dr. Van Dusen, three are Holiness churches. They include the Church of the Nazarene, the Church of God of Anderson, Indiana, and the Christian and Missionary Alliance. Ten of the 17, by far the largest segment, fall into the Pentecostal group. They include the Assemblies of God, Church of God of Cleveland, Tennessee; United Pentecostal Church, International Church of the Foursquare Gospel, Pentecostal Church of God in America, The Church of God, Pentecostal Assemblies of the World, the Pentecostal Holiness, and two Negro groups, the Church of God in Christ, and the Apostolic Overcoming Holy Church of God. Falling into the “other” classification and varying all the way from near cults to fundamentalists are the Church of Christ, Seventh-day Adventist, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Independent Fundamental Churches of America.

THE STRENGTH OF THE SO-CALLED ‘THIRD FORCE’

NOTE: These figures cover a 10-year period from 1949 to 1960. The information above was taken from the 1949 and 1960 volumes of the Yearbook of American Churches.

BACK TO THE CHURCH?

What is the future of the “third force?” Dr. Van Dusen gave a partial answer when he wrote, “No one can foretell whether this “third force” will persist into the long future as a separate and mighty branch of Christianity, or whether it will ultimately be reabsorbed into classic Protestantism as many spokesmen of the latter prophesy.…” While “spokesmen” prophesy and perhaps indulge a bit of wishful thinking, the growing strength of the churches in the “third force” certainly would not suggest the deterioration which usually drives smaller movements to merge with larger ones. Dr. Van Dusen enumerated six contributing factors to the vitality of the third force which are likely to keep it alive and active for many years to come: “(1) They have great spiritual ardor, (2) they commonly promise an immediate, life-transforming experience of the living God-in-Christ, (3) they directly approach people, (4) they shepherd their converts in an intimate sustaining group-fellowship, (5) they place strong emphasis upon the Holy Spirit, and (6) they expect their followers to practice an active, untiring, seven-day-a-week Christianity.” All six of these are accepted in varying degrees by evangelicals, and intense devotion to none of them in itself renders an individual unorthodox.

One writer recently spoke of Christians who accept these beliefs as “fringe,” and “centrifugal” types, but biblically speaking they are actually centripetal, pulling men back to Jesus Christ and back to the center of early Church theology rather than away from it. Many theologians and churchmen have recognized this truth. Speaking recently to a gathering of leaders of his own denomination, Dr. Edward L. R. Elson, pastor of the National Presbyterian Church and President Eisenhower’s minister, said, “… the rising pneumatic sects, with their radiant evangelistic appeal, have something we need.”

Dr. Elson’s speech was reported in the Pittsburgh newspapers on March 5. He was quoted as saying of the “third force” churches, “They have the authentic, New Testament expression more than some of our comfortably-established denominations.” Continuing, Dr. Elson asked his fellow-churchmen, “Is it not tragic that to be Spirit-filled is associated with fanaticism?” Such sentiment has been echoed by many who have awakened to the fact they may have missed the road. Various periodicals throughout the United States, almost simultaneously, have expressed such a feeling. The February, 1958, issue of Coronet carried an article entitled, “That Old-time Religion Comes Back.” The April, 1958, issue of Eternity published an essay titled, “Finding Fellowship with Pentecostals,” while Christian Life and similar publications have issued articles on the influence and spread of parts in the “third force.” Statistics will also bear out progress of the movement.

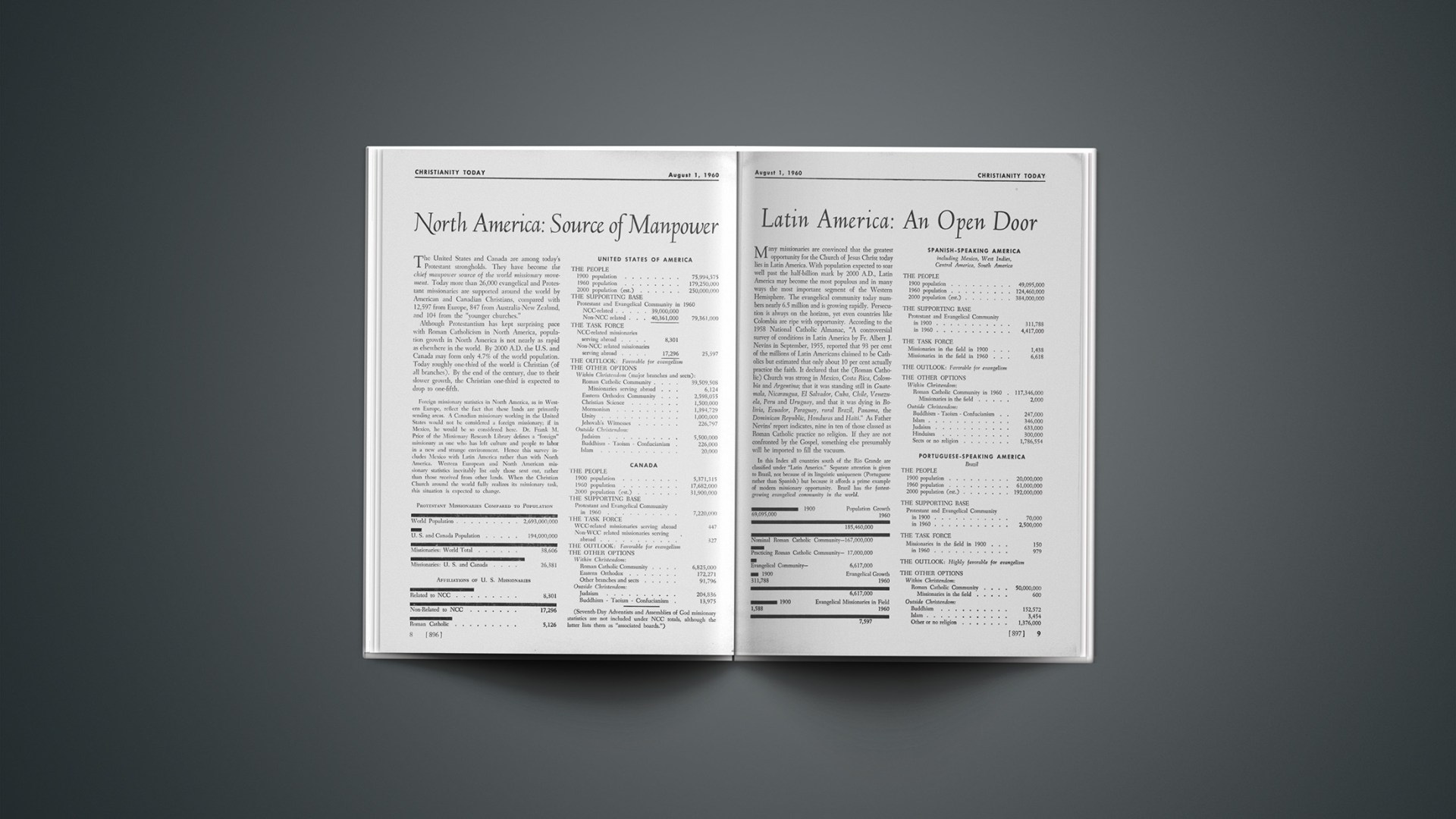

Information released in the 1960 Yearbook of American Churches shows denominations of the “force” have a membership in the United States of more than 4½ million, with more than 50,000 churches. Ten years ago, in 1949, these same churches listed a membership of only slightly more than 2 million, with only 33,000 churches.

It is not possible to say where all of the “third force” is going, for it varies too widely in theology; but for the most part its members are found solidly in the National Association of Evangelicals and are moving with it. The United States membership of the partial list of Pentecostal churches mentioned by Dr. Van Dusen has more than doubled during the past 10 years—jumping from just over 800,000 to more than 1,630,000. Churches in the Holiness group have increased from 341,881 members to more than 480,000 (not including many churches not mentioned by Dr. Van Dusen). Churches in the “other” group have increased from 960,000 (figures not available for the Jehovah’s Witnesses in 1949) to two and a half million.

The reason for growth and the future could be interpreted many ways. Certainly members of the “third force” would not agree that they are headed back to the old-line churches, nor would its leaders plead guilty to abandoning its evangelistic verve. There is permanence in the “third force,” and the evangelistic outreach of a major part of it is sufficient to bring increasing growth in the years ahead. More important, any heaven that makes no room for a major part of the “third force” is likely to be a suburb rather than the main city.

The First Encounter

Never in human history have two opposing powers had a sharper encounter than Christianity and ancient Heathenism, the Christian Church and the Roman State. It is the antagonism between that which is from above, between natural development and the new creation, between that which is born of the flesh and that which is born of the Spirit, while behind all this, according to the Scriptures, is the conflict between the Prince of this world and the Lord from heaven.

Two such powers could not exist peaceably side by side. The conflict must come, and be for life or death. Every possibility of a compromise was excluded. This contest might be occasionally interrupted; but it could end only in the conquest of one or the other power. Christianity entered the conflict as the absolute religion, as a divine revelation, as unconditionally true, and claimed to be the religion of all nations, because it brought to all salvation. A religion coexisting with others the heathen could have tolerated, as they did so many religions. The absolute religion they could not tolerate. Diverging opinions about God and divine things could be allowed, but not the perfect truth, which, because it was the truth, excluded everything else as false. A new religion for a single nation might have given no offence. It would have been recognized, as were so many heathen cults, and monotheistic Judaism as well. But a universal religion could not be thus allowed. The conflict was for nothing less than the dominion of the world. From its nature it could only end in the complete victory of one side or the other.

Christianity entered the field conscious through the assurances of our Lord, that the world was its promised domain. Its messengers knew that they were sent on a mission of universal conquest for their Lord, and the youthful Christianity itself proved that it was a world-subduing power by the wonderful rapidity with which it spread. After it had passed beyond the boundaries of the land and the people of Judaea, after the great step was taken of carrying the Gospel to the heathen, and receiving them into the Christian Church without requiring circumcision or their becoming Jews, it secured in Syrian Antioch its first missionary centre; and from this point Paul, the great Apostle of the Gentiles, bore it from city to city through Asia Minor to Europe, through Greece to Rome, the metropolis of the world. His line of march was along the great roads, the highways of travel, which the Romans had built.

—DR. GERHARD UHLHORN, in The Conflict of Christianity with Heathenism.

Jacob J. Vellenga served on the National Board of Administration of the United Presbyterian Church from 1948–54. Since 1958 he has served the United Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. as Associate Executive. He holds the A.B. degree from Monmouth College, the B.D. from Pittsburgh-Xenia Seminary, Th.D. from Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, and D.D. from Monmouth College, Illinois.