This piece was adapted from Russell Moore’s newsletter. Subscribe here.

After Israel’s recent bombing of Iran, a friend told me about a preacher who asserted that Russia might be the Gog and Magog of the Book of Ezekiel, that Iran might be one of the hostile nations pictured by the prophets, and that all of this just might be pointing toward the imminence of the literal apocalypse.

“Are we going to do this again?” my friend said.

By “this,” he meant the tying of prophecy charts to contemporary geopolitical events in ways that leave audiences hyped up or terrified and then exhausted and even cynical.

Prophecy chart fevers usually skip a generation. One cohort might grow up hearing, as clear as the words on the page, that the Bible teaches no more than 40 years will pass between the founding of the nation of Israel and the Second Coming—but it’s harder to do that after 1988 comes and goes.

A generation accustomed to hearing that the Soviet Union is almost definitely Gog and Magog will be less open to the same sort of confidence when they are told that Iraq is a new Babylon, that Saddam Hussein is a new Nebuchadnezzar, and that, therefore, the Rapture is right around the corner.

The prophecy charts always come back, though, and eventually they gain an audience. Why? With human nature as complicated as it is, one shouldn’t be surprised that there are more cynical reasons and less cynical reasons.

The apostle Paul warned of the time when “people will not endure sound teaching, but having itching ears they will accumulate for themselves teachers to suit their own passions, and will turn away from listening to the truth and wander off into myths” (2 Tim. 4:4, ESV throughout).

At times, the Bible speaks about those “itching ears” as wanting heresy or the justification of sin. At other times, the problem is not the outright contradiction of the Bible but foolish controversies, genealogies, and dissensions (Titus 3:9), or the pull to “quarrel about words, which does no good” (2 Tim. 2:14).

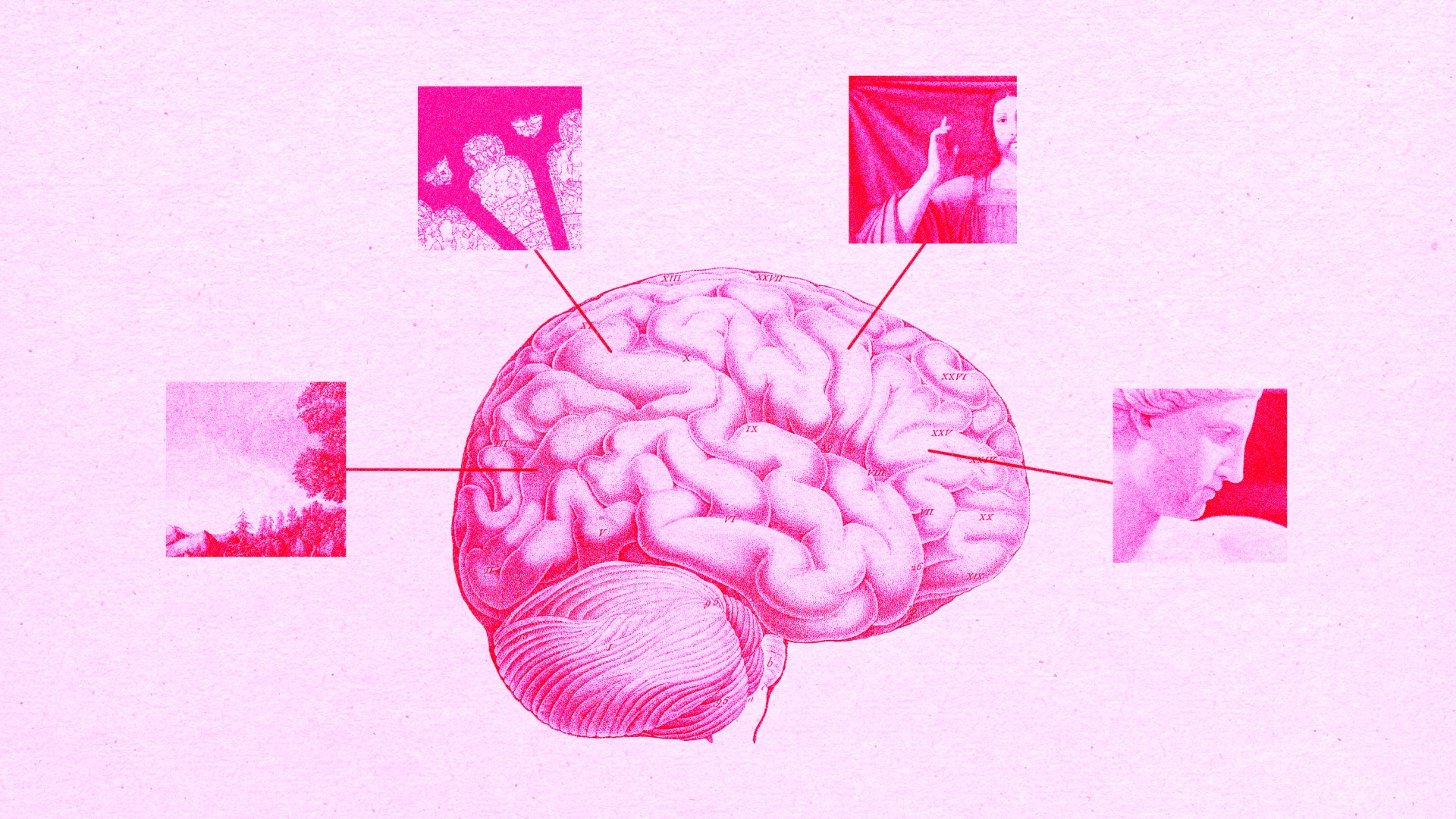

Itching ears don’t imply a group of people who necessarily want something evil, but it does point to those who want something interesting. To have the code that unlocks what’s really going on, to know that one is part of the terminal generation left standing at the end of everything—that can be exhilarating and terrifying all at the same time, like a horror movie or a roller coaster.

Walker Percy wrote that modern people tend to secretly love catastrophes because a hurricane or an earthquake or a war makes a person feel suddenly alive. He argued that what kills us is not danger but a sense of meaninglessness, of everydayness. The sense that everything is falling apart can jolt us out of that kind of deadness.

The protagonist Will Barrett in Percy’s novel The Last Gentleman reflects on how happy his father was when he remembered Pearl Harbor. It was not that his father was a sadist or a masochist. But when he thought about Pearl Harbor, he would suddenly have purpose and life. “War is better than Monday morning,” Will concludes.

Words like “I know what’s happening is the worst thing that leads to the best thing” will gain a much readier audience than “The kingdom of God is not coming in ways that can be observed, nor will they say, ‘Look, here it is!’ or ‘There!’ for behold, the kingdom of God is in the midst of you” (Luke 17:20–21).

Add to that the phenomenon that the monk Thomas Merton once referred to as “mental snake-handling.” Merton asked why small, isolated, persisting congregations of people take up rattlesnakes in a service. It’s because, he argued, surviving the snakes is proof, right now, that one is in God’s favor. Judgment Day is now, it is visible and palpable.

People often look for such a jolt—in metaphorical and not often literal terms—when their lives are bored, over-routinized, or otherwise lacking in purpose or meaning.

“In Christian terms, the mental snake-handling is an attempt to evade judgment when our conscience obscurely tells us that we are under judgment,” Merton wrote. “It represents recourse to a daring and ritual act, a magic gesture that is visible and recognized by others, which proves to us that we are right, that the image is right, that our rightness cannot be contested, and whoever contests it is a minion of the devil.”

The life of faith is difficult. One must walk forward, following a voice one cannot hear audibly, into a future one cannot control. One must entrust one’s life to the mercy of God, demonstrated in a crucifixion and resurrection and ascension that others witnessed firsthand but which we have heard about and found true. A certainty about where events we care about fit into the ultimate plan, and a certainty that we are on the right side of it all, can make that faith feel almost like sight. At least for a little while.

Add to that a scary situation seemingly outside of our control. What should we do about Iran? I don’t know. The possibility of a regional war with a potentially nuclear Iran is enough to set our nerves on edge.

We can debate about what the United States should have done or should do going forward, though easy solutions are impossible and every possibility seems perilous. Given how easily and quickly hostilities can accelerate, it’s not irrational to worry about a potential World War III.

Not many people want another war, and not many people want a nuclear Iran. How to achieve both objectives is fraught with peril and will require wisdom and prudence, much more than we seem to have in this trivial and trivializing time.

That means that we have no easy answers. That’s disconcerting, and it lays on all of us a heavy responsibility to make decisions that will be good and just—whether history continues another trillion years or wraps up tomorrow.

Will Iran tip us into World War III? I don’t know. Or bigger yet, could this be the moment when we see, as Jesus promised, his coming in the eastern skies? I don’t know that either.

We want to see signs that we can track, to hear approaching hoofbeats by which we can know that the final judgment is upon us. Jesus, however, told us that what would shock us about his return is not the drama leading up to it but its ordinariness. People will be marrying and having children and working jobs, he said (Matt. 24:36–44).

That ordinariness leads people to conclude, the apostle Peter warned, that everything would continue as it always has. They will ask, “Where is the promise of his coming? For ever since the fathers fell asleep, all things are continuing as they were from the beginning of creation” (2 Pet. 3:4).

That sense of illusory ease and even boredom is actually heightened over time by promise after promise that this time—I just know it—we are finally at the brink.

The inner core of Jesus’ disciples wanted what we want: the definitive prophecy chart that could be timestamped by events. But Jesus wouldn’t give it. And he told them not to trust anybody who said they could (Mark 13:21–23).

“When you hear of wars and rumors of wars, do not be alarmed,” Jesus said. “This must take place, but the end is not yet” (v. 7). The time between his ascension and his second advent, Jesus said, would be rumbling with birth pains, but none of us have a sonogram to tell us when or where.

Are we in the last days? Yes. Everything from the empty tomb onward are the last days (Heb. 1:2). Could Jesus return at any moment? Absolutely. But can we track that coming based on the bombing schedules of Israel or Iran? No.

We should act, at every moment, whether in peace or in war, as though it might be a millisecond to Judgment Day. But we do not know when that is.

Instead, we have the word of Jesus that the kingdom is advancing, invisibly like fermenting yeast or germinating seed. We have the word of Jesus that he will not leave us as orphans; he will come to us (John 14:18).

That’s all the prophecy chart we need.

Russell Moore is the editor in chief at Christianity Today and leads its Public Theology Project.