In every generation, the church faces a specific set of challenges. In our time, the great challenges concern new technologies and their intersection with what it means to be human.

Conversations among Christians today are rightly focused on digital technology, above all smartphones, social media, and artificial intelligence. There are other technologies worth worrying about, however. And on the human side of things, I see four fundamental challenges facing the church. So far as I can tell, churches and pastors are unprepared to respond with the urgency and authority demanded by the moment.

Each is distinct, but all are related:

- the delay and decline of marriage and birthrates on one hand and the increased rates of indefinite or lifelong singleness on the other;

- the advent of romantic relationships with lifelike chatbots, buttressed by AI-generated, photorealistic pornography;

- the widespread availability of cheap cosmetic surgery and other forms of invasive body modification, from Botox injections to semaglutide shots like Ozempic; and

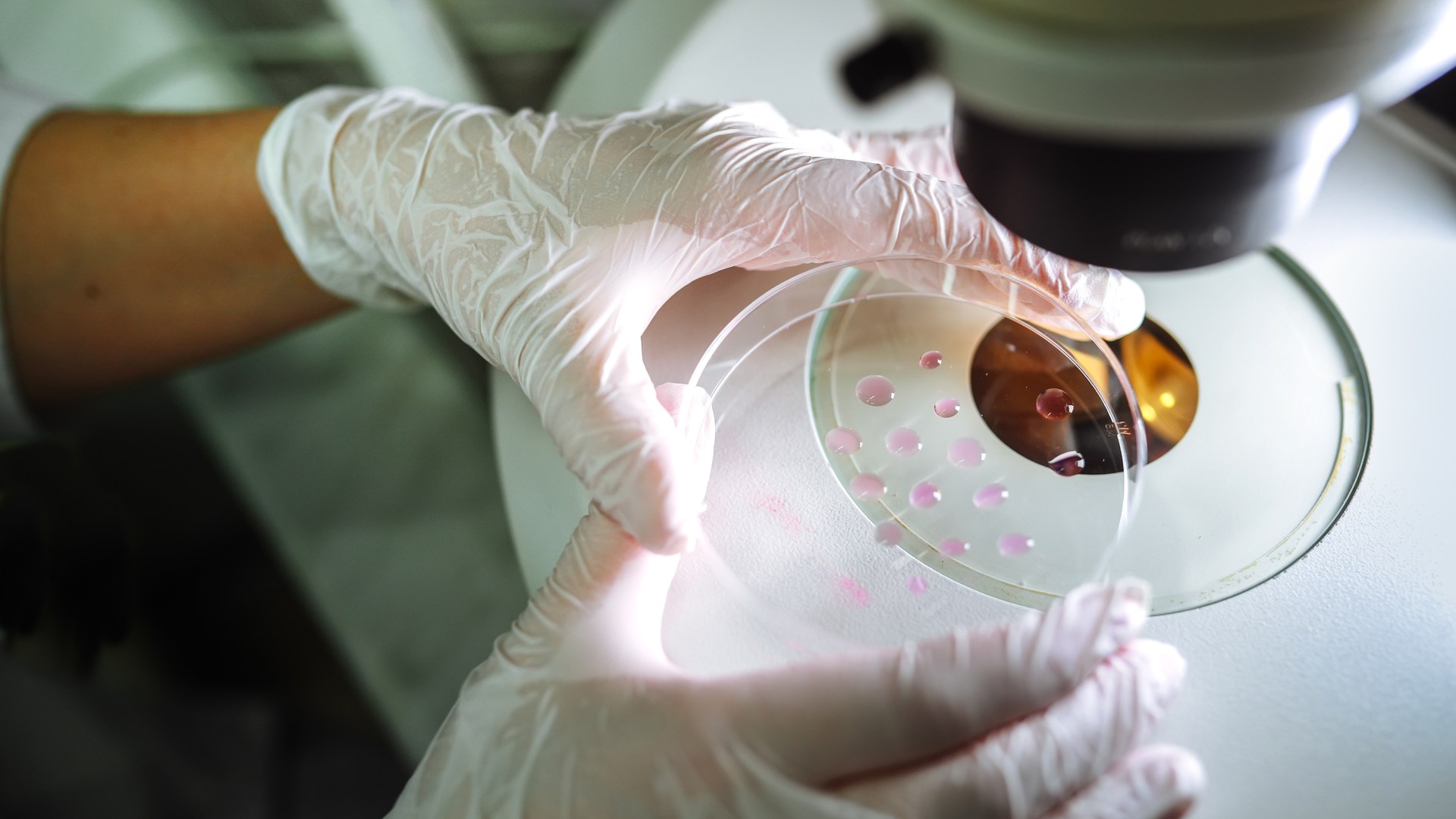

- the extraordinary range of new technologies designed to begin or end human life that are already being used by the rich and will increasingly become affordable for the middle class.

That final biomedical challenge will be my primary focus here. On the reproductive side, it includes artificial contraception, surrogacy, and in vitro fertilization (IVF), as well as egg freezing, genetic editing in the womb, genetic screening of fertilized embryos, and artificial wombs.

Not to be outdone, end-of-life devices match these innovations with ever more ingenious ways to dress up self-slaughter in Hippocratic garb. No longer is euthanasia limited to pills or intravenous drugs; step inside a suicide pod and let the slow release of nitrogen gas dignify your death in a therapeutic key. It affirms your autonomy right up until the moment when there’s no you left to claim it.

You can see how these challenges are inseparable from technological developments. But they are also the product of a society both defined and exhausted by alienation, substitution, and self-enhancement.

Men and women are polarized from each other, failing to pair off and form families. They are, perhaps unwittingly, building lives bereft of siblings and cousins, children and grandchildren, for when the final hour comes. This alienation makes all the more attractive the substitutions of porn, chatbots, surrogacy, and sperm donation—not to mention doctors who administer the final dose instead of priests who administer last rites.

Yet a lingering desire for connection simultaneously pushes us toward enhancements like Botox to suppress the signs of death or perhaps improve one’s standing in the hook-up apps. Screening fertilized embryos is a kind of enhancement too, if that’s the right word for throwing away children deemed unfit.

Some of these challenges are imminent but not yet present: Artificial wombs have yet to be developed for human use; genetic editing isn’t publicly available; and assisted suicide remains illegal in many states.

But for the most part they are present-tense realities. They are already with us, and by “us” I don’t mean a handful of elites in Manhattan and Los Angeles. I mean ordinary folks across the country, including those who fill the pews on Sunday mornings. They’re in red counties and the Bible Belt. They’re not on the outside; they’re not “the world.” They’re on the inside; they’re church folk.

And their churches, for the most part, have little to nothing to say about these things. Why?

One reason is simple enough: The Bible doesn’t talk about them. Open up the glossary in the back of your Bible, and you won’t find ChatGPT, CRISPR, or IVF. There are no chapter-and-verse citations for lip fillers, egg freezing, or practical questions like the “right” age to get married or the “ideal” number of children.

New moral and technological questions require renewed study of Scripture for authoritative guidance. The Bible is not a spiritual FAQ. True, the Bible does answer our biggest questions. But if you live long enough or read your Bible deeply enough, you’ll see that the Bible cannot and will not answer every specific question in advance. It is authoritative in and for all of life, but it doesn’t speak directly or explicitly about every subject. How could it?

Mature Christians, and especially pastors and whole churches, must therefore be able to give confident scriptural answers to new questions even when overt biblical teaching is lacking.

In the absence of explicit answers, many believers and church leaders reach for vague talk about “discernment” or “conscience” or “the Spirit doing a new thing.” This is often well-intended, and has the ring of Christianese, but in practice, discernment is often little more than a permission slip (Prov. 29:18). It ends up making grave ethical matters into subjects for private judgments born of little more than instinct, however sincere or prayerful. It places pressing questions in the category of adiaphora, or indifferent matters.

And if the message is that a given topic is indifferent to the church, then you can bet that ordinary Christians will assume it is likewise indifferent to God. Which, in practice, means: Do as you please.

This is why I began by saying that churches are unprepared for these challenges. They are unprepared because their doctrine of Scripture is insufficient to the scale of the problem and because baked into this doctrine is an altogether too low view of the church—of its authority as well as the authority of its pastors.

In American churches, these inadequacies were long held at bay by a latent social conservatism—people generally esteemed marriage and children and the social supports that make them possible and desirable. This worked in tandem with a wider society whose most pressing social issues (including divorce and poverty) were directly addressed in Scripture. Thus, a broad consensus could be presupposed among the people.

But now neither our surrounding culture nor our churches are doing the formational work to generate a similar consensus, and technological change has made our questions distant enough from biblical teaching that even pastors feel adrift and unsure what to think, believe, or do.

Consider the question of artificial contraception. Beginning in the 1930s, Protestants (including evangelicals) just about sprinted from restricted permission under limited circumstances to no-questions-asked, near-universal adoption of contraceptive methods. The rationale: The Bible doesn’t expressly forbid it. And if the church must be silent where the Bible is silent, then it follows that the absence of a prohibition functions as tacit authorization. If you doubt me, try telling a group of evangelicals that contraception is wrong and see how they react. (If that’s not enough, follow up by saying the same about vasectomies.)

It usually comes as a shock to learn that this issue was never divisive between Catholics and Protestants during the Reformation; in fact, beginning with Luther and Calvin, all major Protestant theologians were united on the question for a full four centuries. I lack the space to summarize their case, but suffice it to say that the Reformers weren’t taking their lead from Rome and would have been happy to dissent had they seen biblical basis to do so.

At a minimum, this kind of unanimity for such a length of time (both before and after the Reformation) ought to persuade Protestants today that contraception is a moral and theological question—that its permissible use is not a foregone conclusion unworthy of discussion. Perhaps it also ought to persuade us that the burden of proof lies with those who would permit its use rather than those who side with tradition.

If contraception was the canary in the coal mine for insufficiently examined sexual ethics, IVF is the same for biomedical ethics. The arc of acceptance has run a similar course; the logic follows a kind of “pro-life consequentialism.” Here the idea is that if a technology purports to save or enrich human life, then the ends justify the means. Since it is impossible to demonstrate that the Bible directly forbids in vitro fertilization, and since one end of the process is a human life, many evangelical pastors are at a loss—if they see this as an ethical issue calling for their input at all.

By far the best, most theologically powerful, and most biblically thoughtful case against IVF was written by Oliver O’Donovan in 1984. Begotten or Made? is a little book that packs a punch. O’Donovan, now 80 years old, is a British ethicist, a Protestant, and an ordained pastor. His book is a model of serious moral engagement that avoids easy answers while looking to Scripture and tradition for authoritative help in navigating new biomedical and technological terrain.

To be clear, my purpose here is not to rehearse the full arguments regarding technological interventions like contraception or IVF. It’s to note the perennial pattern that accompanies them: Questions of legality override those of morality; individual autonomy trumps ecclesial authority; the apparent silence of the Bible speaks louder than the testimony of tradition or theological reason. And so, within just a few years, congregations acquiesce to the “inevitable.” What was once unthinkable becomes the norm.

Some Protestants look to Rome for help here. The social teaching of the Catholic Church is indeed an impressive resource for Christians who feel ill-equipped to draw the logical and moral lines from God’s Word to pressing contemporary questions—from labor unions to marriage to bioethics—that cannot be answered with simple chapter-and-verse-citations. Not a few Protestants have crossed over to Catholicism because of this tradition.

Conversion isn’t necessary, though, to see Rome’s social teaching as a model. It is a standing rebuke to the notion that God is ambivalent about the concrete particulars of our social, sexual, medical, and technological lives. It is equally a rebuke to ideas about the church that would strip ministers of authority, undermine pastoral duty, or leave believers without guidance for these challenges that no one person or couple can handle alone.

God’s people need help. These are the issues that dominate their lives. How can silence be an appropriate response?

It’s true that each of us must pursue the will of God as best we can, in the particular circumstances of our individual lives, in concert with a local congregation, reading the Bible prayerfully with others. But no part of that should lead us to reject or diminish pastoral authority. Without it, we will not live with an absence of authority; rather, we will open up a vacuum that the broader society will all too happily fill. Hence the aforementioned church folk screening embryos, opting for cosmetic surgery, and turning to chatbots for companionship.

For churches to move from silence to authoritative application of Scripture will inevitably be messy. Sometimes pastors will go wrong.

But what’s the alternative? Once we understand the challenges at hand, is silence not a kind of cowardice? However understandable, it is rooted in fear—of offending people, of repeating the mistakes of the past, of interfering in believers’ private lives. Consider that even though purity culture went awry, we still speak to teenagers about dating (another topic never directly mentioned in the Bible). Why would we be silent on these new challenges?

Let me conclude with a final example: the idea of the “seamless garment.” Among pro-life Catholics, this concept is an attempt to connect issues at the beginning and end of life—abortion and euthanasia—to issues during life’s long middle—family, vocation, labor, welfare, poverty, prison, immigration, and so on.

There’s no denying that some versions of the seamless garment suffer from sentimentality while others serve to sneak in partisan policy proposals under the banner of moral doctrine. Even so, learning about the seamless garment in graduate school was a minor revelation for me. It helped me step outside of hot-button debates and, from that wider perspective, grasp the full sweep of human life as a tapestry knit by a loving God.

In particular, it helped me comprehend the law of Moses, the prophets of Israel, the ministry of Jesus, and the church’s tradition as an undivided whole. I came to understand that feeding the hungry, housing the homeless, and caring for single mothers were integral expressions of pro-life commitments, and that affirming this connection in no way detracted from the inviolability of the child in the womb. Given these new challenges around technology and humanity, we need a Seamless Garment 2.0, one that encompasses all I’ve discussed above and more.

I would not presume to tell pastors or fellow theologians exactly what they ought to say. It’s a massively complex range of subjects. But just for that reason, we have to start talking. God’s people are depending on us.

Brad East is an associate professor of theology at Abilene Christian University. He is the author of four books, including The Church: A Guide to the People of God and Letters to a Future Saint.