Is Christian faith reasonable? This question has haunted and delighted the Christian mind since Justin Martyr addressed it in the second century. Believing that the gospel constitutes the truest story about the world, Christians have still had to grapple with how our beliefs interact with outside claims to knowledge and experience of the world.

This tension has led many Christians either to entirely reject or to subordinate themselves to the world’s learning, but it has also been fuel for Christian intellectual culture. And it’s not just a question for intellectuals, an esoteric or cerebral pastime. Everyday believers confront related questions too: Should we accept the scientific evidence for macroevolution, climate change, or vaccine efficacy? Should we attempt to predict the date of the rapture? Should we buy into conspiracism like QAnon?

This cluster of big questions animates Daniel K. Williams’s riveting new book, The Search for a Rational Faith: Reason and Belief in the History of American Christianity. Over the past decade, in books like God’s Own Party and The Election of the Evangelical, Williams (a CT contributor) has become one of our nation’s great historians of 20th-century faith and politics.

In The Search for a Rational Faith, Williams turns his attention to new material: the history of ideas and, largely, prior centuries. He offers an intricate intellectual and cultural history of the enterprise that attempts to defend and promote the intellectual plausibility of Christian faith. (Today we call this enterprise apologetics, but in earlier eras it was known as natural theology, Christian philosophy, or, predominantly, Christian evidences.) Williams surveys apologetics in American Protestantism from the Puritans of the 1600s to Tim Keller in our time, covering a remarkable amount of historical ground in an ambitious, sprawling, rollicking narrative.

Historicization is particularly imperative for apologetics because it’s a discourse too often reduced to abstract ideas shorn of any messy human life—more like mathematics than preaching or conversation. Likely because of this, the history of apologetics has been an undertold story, even as an aspect of broader intellectual histories.

That makes Williams’s contribution all the more impressive. This book will join classics by Avery Cardinal Dulles (A History of Apologetics) and Alister McGrath (Christian Apologetics) in examining not only apologetics’ content but also its historical drama amid different social contexts and cultural pressures.

Williams’s book chronicles three epochal shifts in Anglo-American Protestant apologetics. First is a movement away from the Calvinist suspicion of reason’s capacity in the domain of spiritual truths.

Early Puritan Calvinism had its own internal scholasticism and intellectual flair, of course, but the Puritans’ ideas about sin made for a grim view of the capacity of human reason outside illumination by the Holy Spirit. This perspective precluded any hopefulness about unconverted people reasoning their way to knowledge of God. Conversion simply had to come first, and counterarguments to Christianity were dismissed as the moral corruption of the damned.

American Christians’ wide embrace of a more optimistic Arminian rationalism in the 18th and 19th centuries, however, opened new space for rational arguments about faith. This theological perspective allowed that the human intellect, though insufficient and distorted by sin, could still reason its way to God and God’s basic truths. And if that were true, then empirical evidence could buttress the credibility of Christian belief and belief in the Bible.

The result was a new flowering of apologetics aimed at providing robust evidence for faith. In America, this Arminian approach fit well with the emerging political scene and benefited from a culture in which Christianity was basically seen as plausible, even among doctrinal outliers such as the deists and Unitarians. This evidentialism became integral to American intellectual culture writ large, including US college curricula, and seemed to harmonize insights from science, logic, history, theology, and morality. In a particular achievement of the book, Williams shows how this widespread apologetics culture influenced the American founders and the cultural penumbra of 19th-century American education.

Then came thinkers like Immanuel Kant, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, and Charles Darwin—and the second major shift. The questions they raised about history, science, and knowledge itself proved deeply destabilizing for the centuries-long apologetics tradition. In Williams’s telling, biological evolution as such was not the primary challenge early on; that was readily finessed by many Christian intellectuals of the time. Far graver difficulty came from historical and religious pluralism and new views of the Bible and its authority in human life.

The third major transition, then, was the shattering of the apologetics tradition as it crashed upon the rock of 20th-century complexity. Mainline Protestants mostly lost faith in the older evidentialism, but at the same time they crafted alluring cases for Christianity grounded in experience, ethics, or civilization. (More recently, many of the erstwhile New Atheists who are newly Christian-curious have gravitated toward such pragmatic, instrumentalist arguments as well.) But eventually, Williams claims, mainliners relinquished even this, entering our own time with only a social-justice framework bereft of any notion of common human truth or rationality to which we can appeal.

This is a somewhat misleading analysis. It’s not as if mainline Protestants have entirely abandoned attempts to compellingly present the Christian faith, though certainly they largely spurn the term apologetics, and their philosophical infrastructure is different. Social-justice traditions themselves can exercise a type of “apologetics of goodness,” the enticing beauty of the lived witness of the saints. In this case, the actual living out and practicing of the way of Jesus’ life and ministry are the embodied persuasion and enticement to Christian faith.

Nevertheless, Williams ends the book seeing evangelicals as the last Protestants to take up apologetics as such in our time, viewing this effort as largely a successful project, especially in its cultural apologetics mode. Yet for all the book’s strengths, I’m left with the unresolved incongruity of, on the one hand, Williams’s claim that evangelicals are the lone (Protestant) defenders of a rational faith and, on the other, the reality that some sectors of evangelicalism seem mired in an anti-truth, anti-scientific, postmodern nihilism of power.

There are a few other limitations to consider, none of which should be taken as impugning a monumental accomplishment overall. The sidelining of Catholic and Orthodox apologetics (the former banished to a Siberian appendix) unfortunately reinforces long-standing patterns in American historical work of overlooking those traditions’ contributions to American life. Here the omission also misses an opportunity for thinking about the dynamics of intra-Christian apologetics.

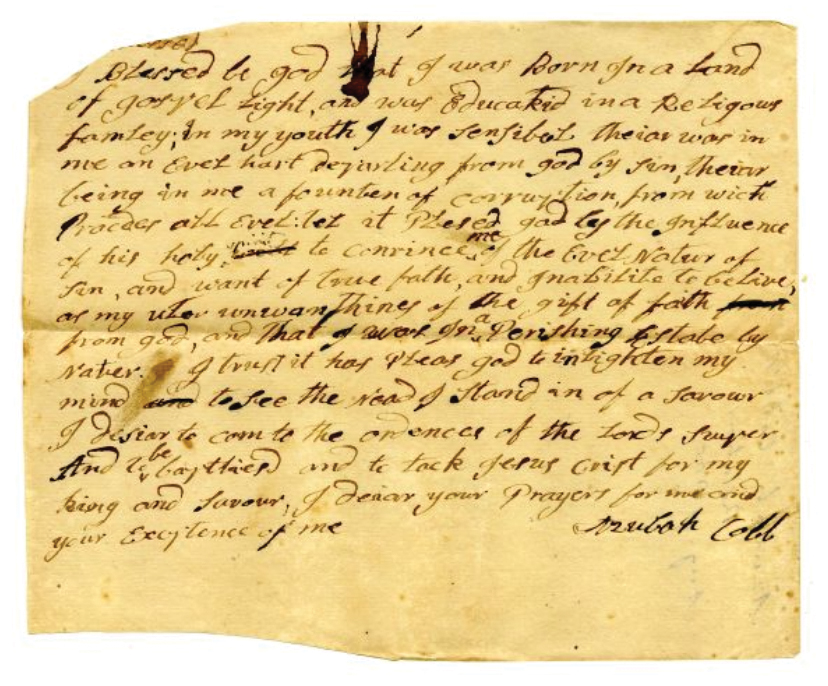

Admittedly, Williams has so much material on the Protestant world that the decision was justifiable. Still, I wish we could have gotten a better index of the popular reception of apologetics on the ground, how average Christians across traditions received and lived these arguments from the intellectual elite.

My biggest concern about the book, however, is that despite serious progress compared to previous works, it needed to delve deeper into the shaping interplay between culture and ideas. For example, apologetics has historically been a very masculinized discourse, but Williams could have been insightful with more substantive attention to female apologists like Mary Astell, author of 1705’s The Christian Religion, as Professed by a Daughter of the Church of England, or Rebecca McLaughlin, a contemporary writer mentioned cursorily. The masculine style of Protestant apologetics deserves more exploration for both its peculiar allures and its blind spots.

Similarly, neurodivergence would have been a helpful issue to explore. Apologetics has played a striking role in the autistic community, both as a project to sooth social frictions and as a catalyst of disenchantment when apologists overpromise and underdeliver.

Likewise, Williams mostly deals with intellectual titans—and does so superbly. But he gives precious little space to the pop apologetics of consumer culture, which has arguably been more influential for a century. On this level, apologetics functions less to convert unbelievers than to help believers bolster their own faith. This can be an authentic intellectual discipleship, but it can also be triumphalist, self-aggrandizing, and ultimately self-deceiving. Adding more on this type of material would have enhanced the book.

The oversight reaches catastrophic proportions with Williams’s entire avoidance of the sheer devastation of the Ravi Zacharias case. This case is so important because it inescapably links apologetics to its social ramifications, dragging it out of its fortress of abstractions. That the best-known Christian pop apologist of the recent past was empowered by that very enterprise to take up serial sexual predation and heinous sexual sin provokes existential questions: about apologetics ensconced in Christian mass marketing and celebrity culture, about Christian conduits of trust and authority, about how views of truth get untethered from beauty and goodness, about how apologetics can be morally simplistic and tragically unloving, about how arguments are always borne by people, flawed people.

Even so, this book tables a rich intellectual feast. It has all the hallmarks of Williams’s previous, excellent work: textured attention to the intricacies of primary sources and sophisticated thinking about historical patterns.

The Search for a Rational Faith offers vividly fresh horizons on Western intellectual giants like Isaac Newton, Robert Boyle, and John Locke for their contributions to Christian apologetics (even when they have eccentric doctrinal beliefs). It also provides some deep cuts on obscure but intellectually potent figures. The book will fascinate anyone interested in apologetics directly, as well as anyone interested in American religions, intellectual history, and higher education more broadly.

There are also lessons for readers to glean. The role of doubt is crucial—and something with which so many of Williams’s figures struggle. His account explores doubt’s role in the mature faith of intellectually curious believers, a worthwhile contrast to some populist Christian cultures’ tendency to smother and expel doubt. There was (at least in certain forms and degrees) deconstruction way before deconstruction was cool, and Williams finds glimpses of intellectual anguish even in the faith of those most publicly zealous for the integrity and stability of their rational arguments for Christianity.

That, however, leads to a countervailing challenge: the role of certainty. So much of the apologetics tradition has been lustful for rational certainty in a way that betrays an underlying anxiety. That is not the foundation of every search for a rational faith, but a search born of anxiety may fall into a kind of idolatry, wanting certainty of conceptual conviction more than the truth of God himself.

At their best, apologetic arguments can be a balm, healing the wounds of anxiety, error, ignorance, and limited perception. But arguments can also be a bludgeon, wielded to domineer, ravage, and demonize. Out of the same mouth can come both blessing and cursing. “My brothers and sisters, this should not be” (James 3:10).

The Search for a Rational Faith could be an occasion for a renewal of apologetics and a celebration of what it has accomplished historically. But let it also be an occasion of reckoning with the hardest, most agonizing, and self-reflective questions about apologetics, as befits followers of the one who said the truth will set you free.

Daryn Henry is an assistant professor of religious studies at the University of Virginia and the author of A. B. Simpson and the Making of Modern Evangelicalism.