All Kathryn Roelofs knows about her birth is that it took place in Seoul in 1984.

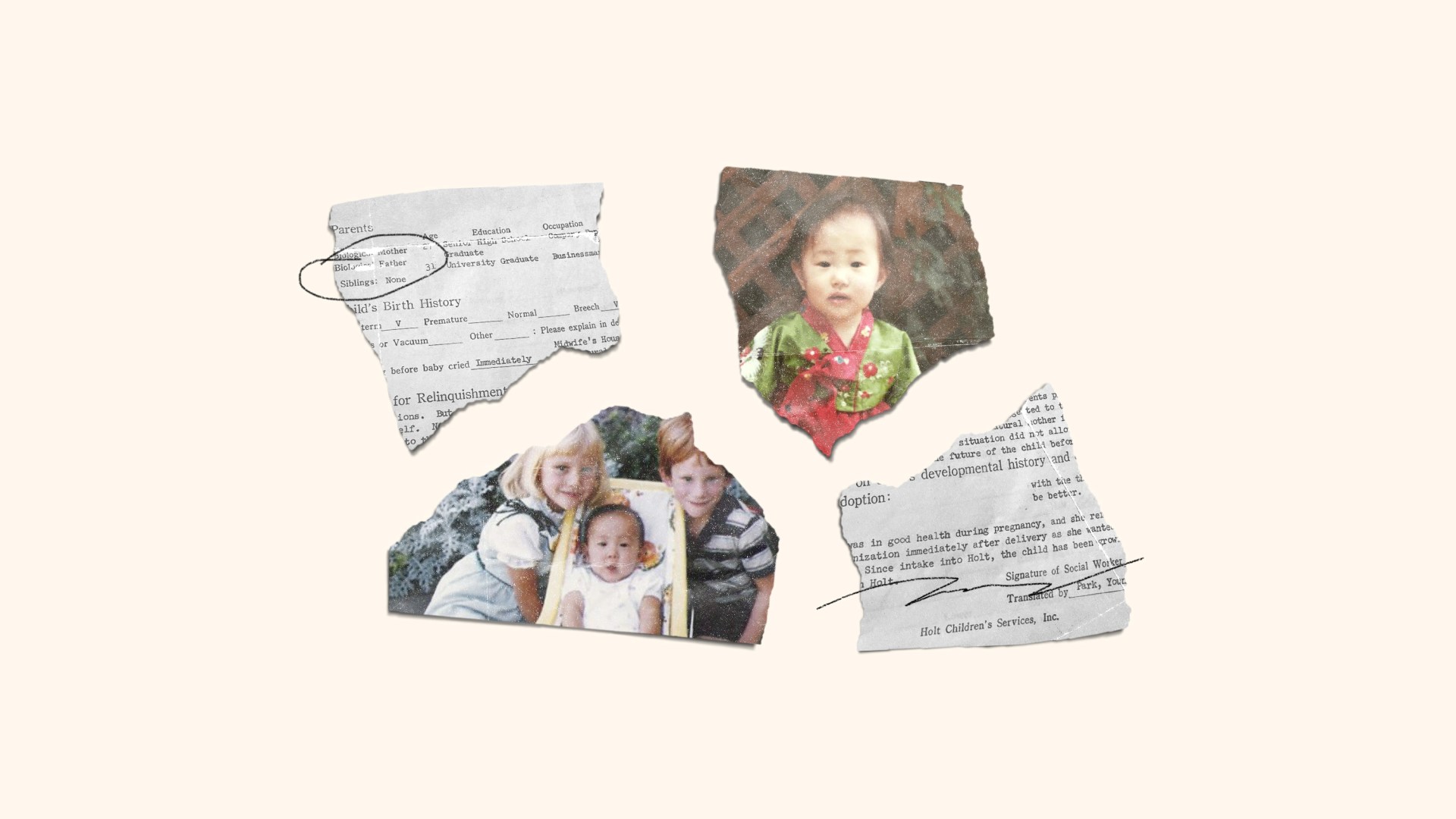

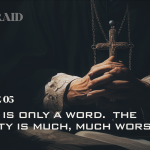

Her unmarried mother put her up for adoption right away. At four and a half months old, she flew to the US, one of five babies traveling with two individuals affiliated with Holt Children’s Services of Korea. The people these South Korean children would call their parents—a group of families from the Christian Reformed Church—waited on the other side.

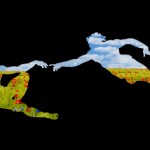

Roelofs grew up in Denver, a mostly white community where she rarely saw people who looked like her. Her birth mother had named her Tae Hee Jung, and her adoptive parents decided to keep Tae (pronounced “tay”) as her middle name. Still, with her traditional first name and Dutch surname, Roelofs struggled to pronounce or explain this nod to her background.

As with her name, Roelofs’s family gave her opportunities to learn about her Korean heritage. They loved and cared for her. She can see herself as a success story for international adoption. But Roelofs still holds lingering questions about her identity.

“Being an adoptee feels like wearing a garment that doesn’t fit quite right,” the 41-year-old said. She has never met her birth parents, and she doesn’t know if her father is even aware of her existence.

Adoptees tend to imagine their biological parents choosing to place them with other families due to circumstances, but a recent investigation uncovered that for some South Koreans, adoption wasn’t their choice at all.

According to a 2024 Associated Press report, the government conspired with agencies to take children to fill the overseas adoption pipeline—kidnapping kids off the streets and removing them from hospitals, where officials told parents that their newborns had died or were too sick to make it.

A Geneva-based adoption agency raised concerns about South Korea’s adoption practices being financially motivated as early as 1966, another AP report stated. A government audit in the ’80s found that adoption agencies had made illegal payments to hospitals after procuring babies from them, the same report revealed.

Horrified, Roelofs called the news “every adoptee’s worst nightmare come true.”

“If I think about the fact that a woman … gave birth to me and then I was taken from her and sold for profit and ended up in this life that I have now,” she said, “it’s almost too overwhelming to think about for too long.”

In interviews with CT, adoptees and advocates from South Korea grieved the adoption-fraud findings, which have spurred Christians in the country to reevaluate the church’s role in adoption.

Since the 1950s, South Korea has sent around 200,000 Korean children to families in the United States, Europe, and Australia. Adoption cases ramped up in this period after the Korean War as people sought to rehome war orphans, especially those of mixed-race heritage who were typically seen as outcasts. The government also viewed adoption as a way to reduce social welfare spending.

Adoptions later surged in the 1980s, with children from South Korea composing 60 percent of global intercountry adoptions in this time. The government began curtailing international adoptions from the ’90s after the 1988 Olympics drew negative attention to the country’s “baby trade” and caused national embarrassment. But thousands of children continued to be adopted overseas in the early 2000s.

From the 1970s, two-thirds of Asian children adopted in the US came from South Korea. But in recent years, international adoptions out of South Korea have decreased as Christian adoption agencies in the US like Bethany Christian Services cease international placements.

On October 1, South Korea announced changes to its adoption process. It will permit international adoption only in cases when agencies cannot find a suitable family in the country. Even then, the government must review each overseas adoption case and determine it to be in the child’s best interest.

The move corresponds with the nation ratifying the Hague Intercountry Adoption Convention, guidelines for countries to protect children’s fundamental rights during adoption and to prevent abduction or trafficking. Earlier this year, South Korea admitted to the “mass exportation of children” that enabled adoption agencies to reap larger profits.

The country’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission found 56 human rights violations among the 98 cases it investigated. Yet the commission halted its work in May, citing differing opinions among the commissioners and a lack of time to investigate.

Christian adoption agency Holt Children’s Services of Korea faces allegations of fraud and illegal adoptions, which the organization has denied. Holt International’s retired vice president Susan Cox—herself adopted from South Korea through Holt in 1956—told CT that adoptees and anti-adoption activists have unfairly labeled adoption agencies as bad. Holt split in 1977 to form Holt International as a separate US-based agency.

Founders Bertha and Harry Holt, an evangelical couple from Oregon, began the agency in 1955 after bringing 12 children to America. Eight of them would become part of the Holt family. Korean newspapers praised Harry as the “father of Korean adoption” while people dubbed Bertha the “Apostle of Korean orphans,” according to researcher Soojin Chung, who chronicled the history of Korean adoption.

When children arrived at an orphanage, Holt prioritized caring for them, making them feel safe, and providing them with food or medicine, Cox said.

“The idea of keeping records and all of the information—that just didn’t have the importance [then] because you were thinking of the moment. You weren’t thinking ahead,” Cox said. “As time went on, those records were much more complete. But [they were] not consistent.”

Adoption agency workers said there were no processes in place to verify a child’s background in the ’80s. Some agencies pressured parents to give up their children so they could lead better lives in the West. Some adoptees learned that their paperwork had been faked, describing them as abandoned when they had living relatives or had been taken from their biological parents.

After the commission’s report found the government responsible for adoption fraud, South Korean president Lee Jae-myung apologized in October for the government’s failure to prevent these abuses.

Korean evangelicals like Kim Do-hyun, founder of KoRoot, a Christian adoption advocacy ministry based in Seoul, had a more critical response.

Adoption fraud is a “state-driven act—an actual crime,” Kim said. “These false records erased the truth of [a person’s] birth and enabled abuse, alienation, and despair. The sorrow these individuals carry might never have existed if their records had not been falsified.”

In South Korea, the pressure to profit from adoptions abroad came alongside the social stigma surrounding domestic adoptions.

South Koreans were less likely to open their homes to nonbiological children due to cultural regard for familial bloodlines. Confucianist beliefs emphasize maintaining ties with ancestors, and families keep records to document their lineage across generations.

Korean adoptee Cam Lee Small saw the adoption stigma linger for decades. Adopted at 3 and a half, he boarded a plane to Chicago, where he met strangers of Caucasian descent who would become his parents. He ran back onto the airplane screaming for his mom.

Small, who grew up in Wisconsin and now lives in Minnesota, visited South Korea in 2011 to connect with his birth family. He sobbed in a taxi after his birth mom canceled their initial meeting. “Why did this happen? Where’s my mom, and when do we get to meet? This should have been my home,” Small thought to himself.

As Small wrestled with these questions, he knew he had to make a choice in what he understood as God’s divine purpose for his life. “That choice was: I believe that God is good. I believe there is some meaning I can take away from this to be used toward something life-giving,” he said.

The next day, the phone rang. The adoption agency worker said his birth mom now wanted to see him.

Small grew to recognize the stigma that his birth mom had endured as a single woman in Korea who carried the secret shame of having a baby out of wedlock. “I started to have more sensitivity for my birth mom, more empathy for her,” he said. “She was holding a lot of pain as well, and there was a lot on her heart that hadn’t been processed.”

Small hopes to continue eradicating stigma on a larger scale by increasing adoption literacy across the US, particularly among professional child-welfare workers, families, counselors, and organizations.

Other evangelicals want to galvanize changes to how South Korea’s government and churches engage negative perceptions of adoption.

Churches in South Korea often focus on evangelism over outreach to socially marginalized people, like single mothers, according to Kim, KoRoot’s founder.

Many single mothers relinquish their children because of familial and societal pressures and systemic poverty.

“The church’s failure to respond to the pain of women and the vulnerable shows how far we have strayed from Christ’s example, [as he] welcomed and embraced the weak,” Kim said.

KoRoot has supported organizations like the Korean Unwed Mothers’ Families Association, which provides emergency shelter and mental health care for single mothers in the country, and has urged the government to live up to the UN’s Convention on the Rights of the Child, which South Korea ratified in the early 1990s.

KoRoot has also been active in supporting Korean adoptees. It cosigned adoptee statements that called for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to conduct investigations on 367 overseas adoptions. And for two decades, it operated a guesthouse for overseas adoptees and their families to stay in while it helped them search for their birth families.

The guesthouse had a shared kitchen, men’s and women’s dormitories, and rooms for couples or families. It housed more than 5,000 families until it closed in 2023, when the nonprofit returned the property to its original owner, Kim said.

“Adoption is not merely a personal act of charity—it is a collective, missional task for the church and society,” Kim added.

Oh Chang-hwa, who leads Onnuri Church’s adoption ministry, J-Home, does not believe that adoption agencies forged or manipulated documents, but that adoption agencies faced many limitations in their work, like inadequate record-keeping infrastructure, in the ’70s and should not be judged by today’s standards.

“Korea was still recovering from war, with many children abandoned or left in orphanages, and agencies did the best they could within those constraints,” Oh said. “While acknowledging that some adoptees tragically suffered abuse or had difficulties, such cases should be treated as individual criminal acts, not as a problems inherent to adoption itself.”

J-Home oversees a network of adoptive families within South Korea and supports families who are interested in adopting.

“In Korea, the domestic adoption rate is tragic,” Oh also said. “That’s why we continue to emphasize that the essence of family and covenant is not blood but love and commitment.”

James 1:27, which exhorts believers to “look after orphans and widows in their distress,” led Oh to adopt his twin daughters in 2011. Adoption is a “divine command—an honorable and holy act of obedience,” he added.

President Lee supports legal abortion, and recent initiatives under his administration are “triggering a wave of activism” among Christian adoptive families and churches, Oh said.

Oh, who also serves as president of the National Adoptive Families Association of Korea, sometimes fosters infants, some left in baby boxes in Seoul. Jusarang Community Church installed the first baby box on its exterior wall in 2009, and the church has saved more than 2,000 young lives since then.

Two years ago, there was a sharp increase in the number of babies left in these baby boxes after South Korea passed an amendment to the Special Adoption Act, a 2012 law that mandated parents register newborn babies at birth, Oh said.

Oh strongly opposes the Special Adoption Act. Previously, a woman could proceed with adoption without registering her baby, but now that women must put their children’s births on paper, some opt to place their babies in the baby box rather than go through with the official process, Oh also said.

Roelofs, who works as a worship consultant with Christian ministries, continues to struggle with the “rosy metaphor” of adoption that she finds prevalent in Christian conversations. Often, she says, the identity that an adoptee leaves behind appears “inherently bad or sinful” while adoptive parents are regarded as saviors.

As she searched Scripture for words that would give voice to the pain of adoption that she felt, she landed on Romans 8:18–25, which talks about creation waiting with longing and groaning.

“Jesus knew something of that suffering and of that trauma [that adoptees feel],” she said. “I find great comfort in that.”

Another source of comfort: her Korean name, which a friend told her means “May she have joy.” Her birth mother gave her a name with hope, Roelofs realized. “It’s like a prayer, right?”

In 2006, Roelofs traveled to Seoul in hopes of meeting her birth mother. At Holt Children’s Services of Korea, a caseworker opened a file in front of her, and the first thing she saw was a photo of her adoptive family in Denver. The file also held little information about her birth parents.

Seeing that photo gave Roelofs a sense of finality and quelled her curiosity toward searching for her family origins, although every time she celebrates her birthday she wonders whether her birth mother thinks of her.

In her adoption case file, Roelofs decided to leave behind a photo of her college-aged self alongside her contact information. In her eyes, it’s her way of telling her birth family, “Hi, here I am. Here’s all the ways that ‘May she have joy’ has come to fruition.”

This story has been updated to clarify Oh Chang-hwa’s position on adoption.