If you want to quickly determine whether someone is the type to give out unsolicited medical advice, tell the person that over the past year you’ve received more Botox injections than Kim Kardashian, Jennifer Aniston, and Gwyneth Paltrow combined.

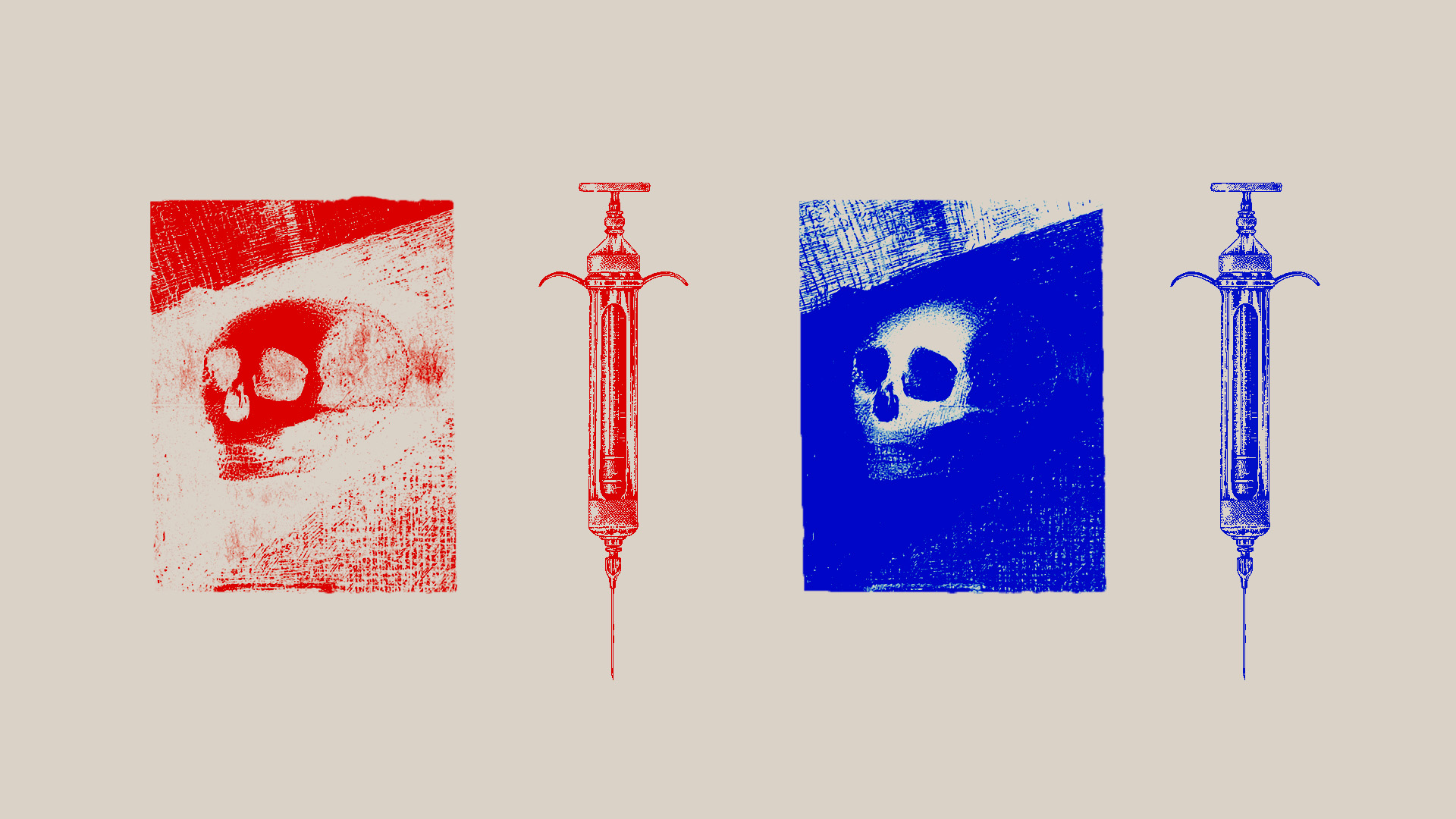

That doesn’t sound good, does it? And yet that was my reality back when I got Botox for chronic migraines—one of the neurotoxin’s many medical uses. Relaxing muscles by inhibiting nerve endings, it’s also good for treating muscle tremors and tension, overactive salivary or sweat glands, and conditions related to the vocal cords.

There are plenty of other things we do in the pursuit of health that don’t seem all that … well, healthy. The keto diet, for example, is touted as effective for weight loss but involves eating so much fat it can aggravate heart problems. Another recent fad—intermittent fasting—can be dangerous for those who struggle with either metabolic conditions or disordered eating.

With Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s recent efforts to “Make America Healthy Again,” some (stereotypically) conservative Christian views on health and wellness are having their moment. There’s been a groundswell in vaccine skepticism, as well as rising opposition to Big Pharma and processed foods—all hallmarks of “crunchy Christians” whose views on health and wellness were, until recently, somewhat fringe.

Some of these developments are undeniably good—the push for healthier food, for example. But others, like vaccine skepticism and the eschewal of the medical establishment, are contentious, including within Christian circles. This brings us to a crossroads: What do we do when Christians disagree on something as fundamental as what’s healthy and what’s not? Is there any unity to be had amid these hotly debated differences?

Back to Botox, which I received four times a year for many years—and which Kennedy has tried as a treatment for the neurological condition that affects his voice. I had chronic migraines for two years before I took the plunge. The idea of injecting a toxin into dozens of points all over my head freaked me out. (Botox treatments for chronic migraines have high doses, roughly four times what’s usually administered for cosmetic purposes.)

I also agonized over its potential long-term side effects, which according to many medical studies are negligible but according to much of the internet are severe. There are all sorts of horror stories, ranging from losing feeling in your face to dying from the Botox getting into your bloodstream.

There were also, of course, all the opinions I heard from seemingly everyone—from my physical therapist to my closest friends. Botox is poison. The studies on it are biased. It’s not worth it. Most celebrities won’t even go near that stuff these days. I have a friend who got Botox, and now her face is stuck in a permanent frown.

Receiving unsolicited feedback on my medical decisions was nothing new. By now, I’ve almost gotten used to it. But with Botox, I couldn’t brush off the concerns as easily, because they were concerns that I largely shared.

From cryogenics to biohacking and the newfound field of longevity science, much of modern society is obsessed with being as healthy as possible for as long as possible. Even medically assisted suicide, though seemingly in opposition to the “live forever” movement, is just the other side of the same coin. “At the center of the world’s fastest-growing euthanasia regime is the concept of patient autonomy,” claims a recent article on medically assisted suicide. Whether by extending the human lifespan or by cutting it short, both fields aim to control what is, to many people, the scariest, most uncontrollable phase of life: death.

As a Christian who has spent many years in pain, I’m decidedly not obsessed with being in control of when and how my life ends. On the one hand, coming so frequently face-to-face with my own frailty has me agreeing with Paul, who wanted to be “away from the body and at home with the Lord” (2 Cor. 5:8). On the other, whenever I focus on God’s promises, I realize that my earthly life has value, even the scary parts that I’d rather avoid.

There’s nothing wrong with wanting to live a long, healthy life here on earth. But at the same time, when it comes to when we die and how, Christians should know we have nothing to fear. (As a well-known Easter hymn says, “Lives again our glorious King … / Where, O death, is now thy sting? … / Once he died our souls to save… / Where thy victory, O grave? Alleluia!”) This fearlessness makes us salt and light to a world that’s controlled by the uncertainties of mortality, and it should also change how we approach the topics of health and wellness.

From microplastics to food dyes to injectable neurotoxins, modern life has no shortage of real threats to our health. And as a professional patient, I have many reservations about Western and alternative medicine alike. But when I remove the fear of death from my medical decision-making, it frees me up to consider more than what is best for my physical body. What is best for my mind, my soul, and the people around me? And most importantly, how can I make this decision in a way that offers hope to a watching world? When the fear of dying predominates these decisions, it also overrides all these nuances.

In spite of the frequent exhortations not to do Botox, many of which I found difficult to shake, I ultimately decided to go ahead with the treatments. Why? At the time, I was living in constant, high-level pain. My mental health was deteriorating, my spiritual life was basically nonexistent, and even my marriage was suffering beneath the pressures of my illness. After my first treatment, I had some pain-free days—not many, but more than the zero I’d had before. And that, in the end, seemed worth all the potential downsides.

Was getting Botox the right decision? I don’t know. Maybe my face will droop in a few years, or maybe future research studies will show that Botox has shortened my lifespan. This choice never felt black-and-white. But at the time, one option felt like giving in to fear over a future that God held firmly in his hands, and the other felt like his provision for the season I was in.

Our lives are full of medical gray areas, and Christians will likely continue to disagree on how best to steward and care for our physical bodies. But one thing we can and should agree on is that our lives are not our own and that our calling as believers is to show the peace of Christ to a world darkened by the fear of death.

Natalie Mead is currently pursuing an MFA while writing a memoir about chronic pain, relationships, and faith. Read more of her writing at nataliemead.com.