Two staff members of the evangelistic organization Jews for Jesus have agreed to an out-of-court settlement of their suit against the University of California and the Los Angeles Olympics Organizing Committee (LAOCC).

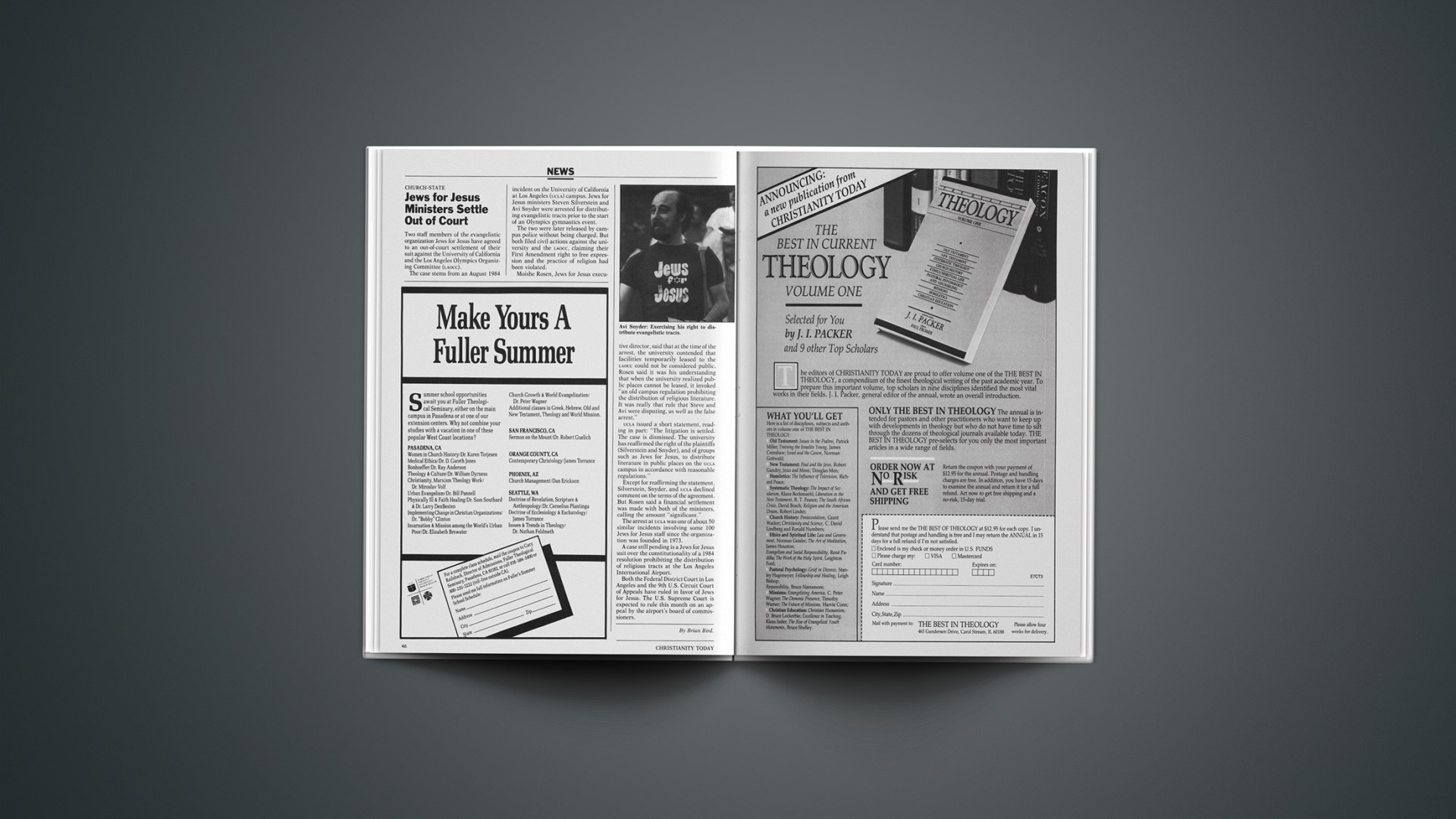

The case stems from an August 1984 incident on the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) campus. Jews for Jesus ministers Steven Silverstein and Avi Snyder were arrested for distributing evangelistic tracts prior to the start of an Olympics gymnastics event.

The two were later released by campus police without being charged. But both filed civil actions against the university and the LAOCC, claiming their First Amendment right to free expression and the practice of religion had been violated.

Moishe Rosen, Jews for Jesus executive director, said that at the time of the arrest, the university contended that facilities temporarily leased to the LAOCC could not be considered public. Rosen said it was his understanding that when the university realized public places cannot be leased, it invoked “an old campus regulation prohibiting the distribution of religious literature. It was really that rule that Steve and Avi were disputing, as well as the false arrest.”

UCLA issued a short statement, reading in part: “The litigation is settled. The case is dismissed. The university has reaffirmed the right of the plaintiffs (Silverstein and Snyder), and of groups such as Jews for Jesus, to distribute literature in public places on the UCLA campus in accordance with reasonable regulations.”

Except for reaffirming the statement, Silverstein, Snyder, and UCLA declined comment on the terms of the agreement. But Rosen said a financial settlement was made with both of the ministers, calling the amount “significant.”

The arrest at UCLA was one of about 50 similar incidents involving some 100 Jews for Jesus staff since the organization was founded in 1973.

A case still pending is a Jews for Jesus suit over the constitutionality of a 1984 resolution prohibiting the distribution of religious tracts at the Los Angeles International Airport.

Both the Federal District Court in Los Angeles and the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals have ruled in favor of Jews for Jesus. The U.S. Supreme Court is expected to rule this month on an appeal by the airport’s board of commissioners.

By Brian Bird.