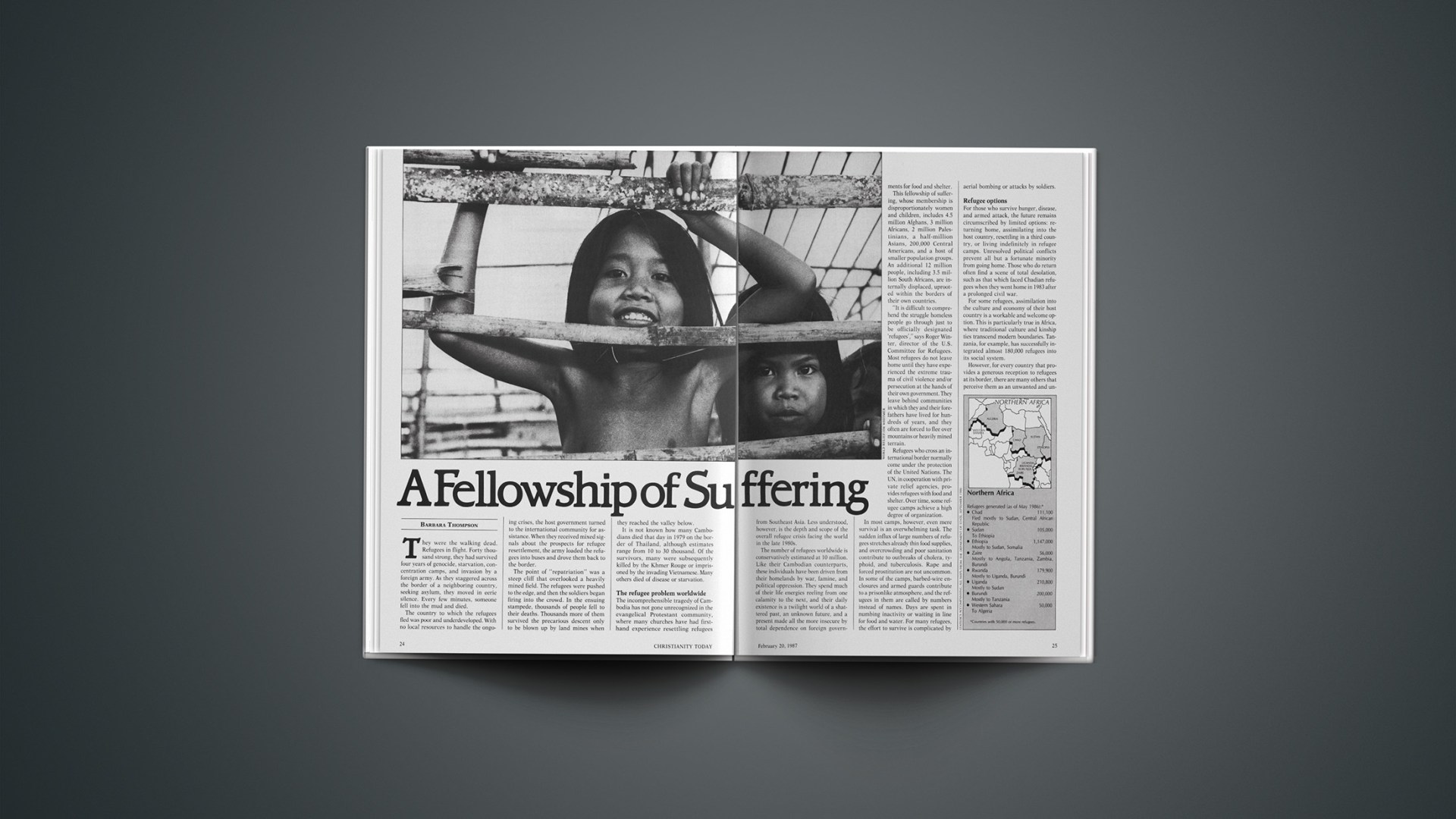

They were the walking dead. Refugees in flight. Forty thousand strong, they had survived four years of genocide, starvation, concentration camps, and invasion by a foreign army. As they staggered across the border of a neighboring country, seeking asylum, they moved in eerie silence. Every few minutes, someone fell into the mud and died.

The country to which the refugees fled was poor and underdeveloped. With no local resources to handle the ongoing crises, the host government turned to the international community for assistance. When they received mixed signals about the prospects for refugee resettlement, the army loaded the refugees into buses and drove them back to the border.

The point of “repatriation” was a steep cliff that overlooked a heavily mined field. The refugees were pushed to the edge, and then the soldiers began firing into the crowd. In the ensuing stampede, thousands of people fell to their deaths. Thousands more of them survived the precarious descent only to be blown up by land mines when they reached the valley below.

It is not known how many Cambodians died that day in 1979 on the border of Thailand, although estimates range from 10 to 30 thousand. Of the survivors, many were subsequently killed by the Khmer Rouge or imprisoned by the invading Vietnamese. Many others died of disease or starvation.

The Refugee Problem Worldwide

The incomprehensible tragedy of Cambodia has not gone unrecognized in the evangelical Protestant community, where many churches have had firsthand experience resettling refugees from Southeast Asia. Less understood, however, is the depth and scope of the overall refugee crisis facing the world in the late 1980s.

The number of refugees worldwide is conservatively estimated at 10 million. Like their Cambodian counterparts, these individuals have been driven from their homelands by war, famine, and political oppression. They spend much of their life energies reeling from one calamity to the next, and their daily existence is a twilight world of a shattered past, an unknown future, and a present made all the more insecure by total dependence on foreign governments for food and shelter.

This fellowship of suffering, whose membership is disproportionately women and children, includes 4.5 million Afghans, 3 million Africans, 2 million Palestinians, a half-million Asians, 200,000 Central Americans, and a host of smaller population groups. An additional 12 million people, including 3.5 million South Africans, are internally displaced, uprooted within the borders of their own countries.

“It is difficult to comprehend the struggle homeless people go through just to be officially designated ‘refugees’,” says Roger Winter, director of the U.S. Committee for Refugees. Most refugees do not leave home until they have experienced the extreme trauma of civil violence and/or persecution at the hands of their own government. They leave behind communities in which they and their fathers have lived for hundreds of years, and they often are forced to flee over mountains or heavily mined terrain.

Refugees who cross an international border normally come under the protection of the United Nations. The UN, in cooperation with private relief agencies, provides refugees with food and shelter. Over time, some refugee camps achieve a high degree of organization.

In most camps, however, even mere survival is an overwhelming task. The sudden influx of large numbers of refugees stretches already thin food supplies, and overcrowding and poor sanitation contribute to outbreaks of cholera, typhoid, and tuberculosis. Rape and forced prostitution are not uncommon. In some of the camps, barbed-wire enclosures and armed guards contribute to a prisonlike atmosphere, and the refugees in them are called by numbers instead of names. Days are spent in numbing inactivity or waiting in line for food and water. For many refugees, the effort to survive is complicated by aerial bombing or attacks by soldiers.

Refugee Options

For those who survive hunger, disease, and armed attack, the future remains circumscribed by limited options: returning home, assimilating into the host country, resettling in a third country, or living indefinitely in refugee camps. Unresolved political conflicts prevent all but a fortunate minority from going home. Those who do return often find a scene of total desolation, such as that which faced Chadian refugees when they went home in 1983 after a prolonged civil war.

For some refugees, assimilation into the culture and economy of their host country is a workable and welcome option. This is particularly true in Africa, where traditional culture and kinship ties transcend modern boundaries. Tanzania, for example, has successfully integrated almost 180,000 refugees into its social system.

However, for every country that provides a generous reception to refugees at its border, there are many others that perceive them as an unwanted and unbearable burden. When economic and political tensions increase, some refugees are forcibly returned to their homelands. (Forced repatriation is in violation of the United Nations Protocol of 1951, to which most Western nations, including the United States, are signatories.)

For a small percentage of refugees, there is the prospect of resettlement in a third country, usually in the West. Since 1975, this dream has become a reality for over 2 million refugees, half of whom have found permanent homes in the United States. “The U.S. and the Western world have participated in the most dramatic rescue operation in the history of mankind,” says Roger Winter. “There are political leaders who talk about the refugee ‘situation’ as if it is a never-ending problem, but in reality, solutions for individual refugees are found every day of the year.”

The Role Of The Churches

Catholic and Protestant churches, as well as synagogues, have played a major role in the rescue effort, assisting in the resettlement of more than 90 percent of refugees accepted by the United States. The U.S. Catholic Conference alone places approximately half of all refugees, while World Relief leads evangelical Protestant agencies with 62,000 refugees resettled since 1979. Over 2,500 churches have participated in the World Relief program, and many congregations have sponsored more than one family.

The people who sponsor refugees come from every socio-economic level of society. “They run the spectrum from rich to poor, ultraconservative to liberal”, says Dennis Ripley, director of World Relief’s U.S. Ministries. “what they have in common is a willingness to reach out and touch the life of another human being in need.”

Sponsoring churches and families help refugees find jobs and homes, adjust to language differences, and make accommodation to American culture. They also have a unique opportunity to participate in the deep joys and sorrows of the refugee experience. Don Mosley, a member of Jubilee Partners, an intentional Christian Community in Comer, Georgia, that has helped over 950 refugees, remembers a unique worship service with a new group of Cambodian refugees. “We asked everyone to draw a picture of something for which they were grateful to God,” says Mosley.

“The children drew flowers and rainbows. One woman drew a picture of soldiers shooting a man, while in the background a woman and three children ran away.” The woman explained to the group that she and her family had been found by the Khmer Rouge when they tried to leave Cambodia. “My husband stood up and said to the soldiers, ‘shoot me and let my family go.’ This is what the soldiers did. And this is what I’m grateful for—that I had such a husband.”

Human Triumphs And Barbed Wire

Refugees face cultural and language barriers when they resettle in the West, but refugee workers are unanimous in their positive assessment of the resettlement program. They point out that in less than a decade, the first wave of Southeast Asian refugees has achieved an employment rate in the U.S. equal to that of the larger population. Studies also show that, in the long run, refugees pay more into the national coffers in taxes than they take out during their first years in the U.S.

“People sometimes think refugees are the losers of the world,” says Susan Goodwillie, executive director of Refugees International, a refugee advocacy organization. “But in a sense, they are the winners. They have survived the worst. They are human triumphs among the wreckage of other people’s politics.” Unfortunately, the success of the resettlement program represents only a part of the total refugee story in the 1980s. The vast majority of refugees have lived outside of their homeland for at least five years, and have no hope of resettling in a Western country, or in any country. Instead, they and their children will live out their lives in refugee camps, much as the Palestinians have done for generation after generation.

Refugee analysts predict that the number of children growing up behind barbed wire is likely to increase. Current refugee situations remain unresolved, and the political, economic, and social pressures that create new refugees are on the rise. More than 20 percent of the Earth’s surface is under direct threat of desertification, and this land is home to more than 80 million people.

Africa, which produces more refugees than any other continent, now imports a fourth of its grain, although as late as 1970 it was essentially self-sufficient in food production. Throughout the Third World, the high price of loans and the low price of raw materials force governments to give priority to export crops, while local food production is pushed to the infertile margins of available farmland.

Ironically, as the number of refugees grows and the need for asylum increases, the availability of safe haven is decreasing. A general weariness in well-doing has settled over the West, and refugee admissions are dropping accordingly. In the United States, for example, refugee admissions have fallen from a high of 280,000 in 1980 to 67,000 in 1986.

According to Don Bjork, associate executive director of World Relief, this decline does not reflect a corresponding decline in the ability of church-related agencies to resettle refugees. “The consistent position of these agencies is that we can handle higher admission ceilings,” says Bjork. “On any given day, we might have trouble finding a sponsor for a particular family, but over-all, when there is a need, churches rise to meet it.”

Despite the sustained interest of church groups in resettlement programs, refugee analysts detect a growing cynicism in political circles toward the plight of refugees and a general backing away from the worldwide relief system coordinated by the United Nations.

“Refugee protection is one of the few areas in which the world community has developed a structure that works,” says Roger Winter. “And if anything will translate into real trouble for the little people of this world, it will be when the U.S. and its Western allies begin to walk away from refugee problems. We don’t even have to wash our hands 100 percent. We just have to stay on our present path and it will mean a setback in refugee doctrine and practice.”

Policy Problems

Winter and other refugee advocates point to three problem areas in U.S. refugee policy: the interdiction (or legal prohibition) of Haitian refugees, the long-term detention of asylum seekers; and discrimination against Central American refugees. Since interdiction began in 1981, over 6,000 Haitians have been stopped at sea and involuntarily returned to their homeland.

Technically, these refugees are allowed to apply for asylum at the time of interdiction, but no Haitian “boat people” have received asylum since the program began. “It’s not the case that all Haitians qualify for refugee status,” says Winter. “But the average American would be morally offended to know that, in the flood of people fleeing from Duvalier’s regime, not a single individual was granted asylum in the United States.”

Haitians who make it to shore are faced with the prospect of incarceration in one of nine immigration detention centers in the United States. The United States is one of the few Western countries that practices long-term detention of asylum applicants, and refugees from Haiti, Cuba, Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Nicaragua have been detained for up to six years. Currently an estimated 4,000 asylum seekers are being detained in the United States.

Central American Refugees

Perhaps the most controversial aspect of U.S. refugee policy concerns the status of refugees from El Salvador and Guatemala. Since 1945, 90 percent of all refugee admissions into the United States have been persons fleeing from Communist countries. Refugee advocates argue that persons fleeing from right-wing governments, particularly those with which the United States has political ties, have unwarranted difficulty proving their refugee eligibility.

Although the Refugee Act of 1980 provides ideologically neutral standards for determining refugee admissions, of 70,000 spaces available in 1985, 59,000 were allocated to persons fleeing from the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, and Indochina. In the first eight months of 1986, of 3,000 spaces allocated to Latin Americans, none were given to Salvadorians or Guatemalans.

Sen. Mark Hatfield, immediate past-chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee, is among those who believe that the Refugee Act of 1980 has not been fairly applied to Central Americans. In January 1986, Hatfield went to Guatemala to oversee elections and witnessed firsthand some of the conditions that cause Guatemalans to flee their homeland. “There are grave human rights abuses that the U.S. will not acknowledge,” says Hatfield. “And these abuses are producing refugees that the U.S. will not recognize.”

U.S. asylum policy for El Salvador has generated similar criticism. Currently less than 3 percent of Salvadorians who apply for political asylum receive it. Since 1979, over 65,000 Salvadorians have been killed in their homeland (a figure proportionate to over 3 million political assassinations in the United States). An estimated 38,000 have been deported from the U.S.

Hatfield, among others, believes many of these deportations represent inequitable application of the Refugee Act of 1980. This discrimination, he adds, is one reason why the Sanctuary Movement has taken hold in the United States. The Sanctuary Movement, which involves some 270 churches, attempts to provide refugees from El Salvador with safe haven in the United States.

“The Old and New Testaments are full of people who had to choose between the law of God and the law of human beings,” says Don Mosley, who supports the Sanctuary Movement. “But ironically, with respect to Central American refugees, it is not the law itself [the Refugee Act of 1980] that is at fault, but the biased way in which U.S. officials abuse it. In a real sense, the government is breaking the law.”

Laura Dietrich, deputy assistant secretary of the Bureau of Human Rights and Humanitarian Affairs at the State Department, believes that members of the Sanctuary Movement are motivated primarily by their desire to undermine Reagan administration policies in Central America. She also takes issue with the claim that Salvadorians have been treated unfairly. “Conditions in El Salvador are improving, and numerous people are going home,” she says. “Civilian deaths are way down, and there has been reform in the military.”

Dietrich adds that relatively few Salvadorians have been able to demonstrate that they are individually targets of persecution by their government, and that the vast majority who come to the United States are economic immigrants looking for work.

Don Bjork of World Relief believes both the Sanctuary Movement and the U.S. government are falling short of an adequate assessment of the Central American refugee problem. “We aren’t going to change government policy by breaking the law,” says Bjork. “But the current definition of ‘refugee’ needs to be broadened to include people fleeing both persecution and economic hardship. As it is now, when persons trying to enter the U.S. mention that they are starving and can’t get a job, under our law they disqualify themselves for refugee status.”

Against “Compassion Fatigue”

Whatever the future of Central American refugees in the United States, it is likely that U.S. refugee policy will remain highly controversial and politically charged for many years to come. The politicization of refugee matters will affect most deeply that segment of humanity that has already suffered enormously for other people’s politics—refugees themselves.

In the face of the great need of the world’s homeless and the current wave of “compassion fatigue” in the West, the role of the church with respect to refugees becomes all the more critical.

“Our Lord himself was a refugee,” says Ted Engstrom, president of World Vision. “The Bible has a great deal to say about the plight of displaced people, and we know they have a special place in God’s heart.”

Engstrom’s hope is that church leaders and pastors will begin to identify with the suffering of refugees and bring their plight to the attention of their congregations. “We as Christian people in the West are going to face the judgment of God,” says Engstrom soberly. “Thank God for the grace of Christ, but when we have wealthy churches spending $100 million on their buildings without allocating an equal amount for the poor, it is time we rethink our priorities.”

In the upper middle-class suburb of Edina, Minneapolis, a group of five churches representing evangelical and mainline Protestant denominations as well as the Catholic church have followed Engstrom’s advice. In cooperation with World Vision, they have formed a community coalition that sends up to 20 people a year from Edina to famine areas in Kenya and Ethiopia. Volunteers participate in construction, reforestation, dam building, and well digging.

“World Vision took a chance on us, inviting a bunch of naive middle-class Americans to African famine areas,” says Dr. Arthur Rouner of the Colonial Church of Edina. “And in the beginning, we were only thinking of a small, one-time project. But seeing is believing, and our encounter with Third World poverty changed our lives. Now we can say, with John Wesley, that the world is our parish.”

Meanwhile, as Christian leaders attempt to awaken many more churches to the plight of refugees, 10 million men, women, and children wait expectantly for some sign of hope for their future. Each day, many of them will receive a notice from a foreign government, turning down their application for asylum and suggesting that they seek resettlement elsewhere. The realization that there is no elsewhere will be a bitter one. Across the water, those who listen carefully may hear an echo of the plea made by a young Vietnamese girl: “Help us to stand. And we will walk by ourselves.”

Barbara Thompson is a freelance writer living in Brevard, North Carolina. Her latest book is Dying for a Drink (Word, 1985), written with Anderson Spickard, Jr., M.D.