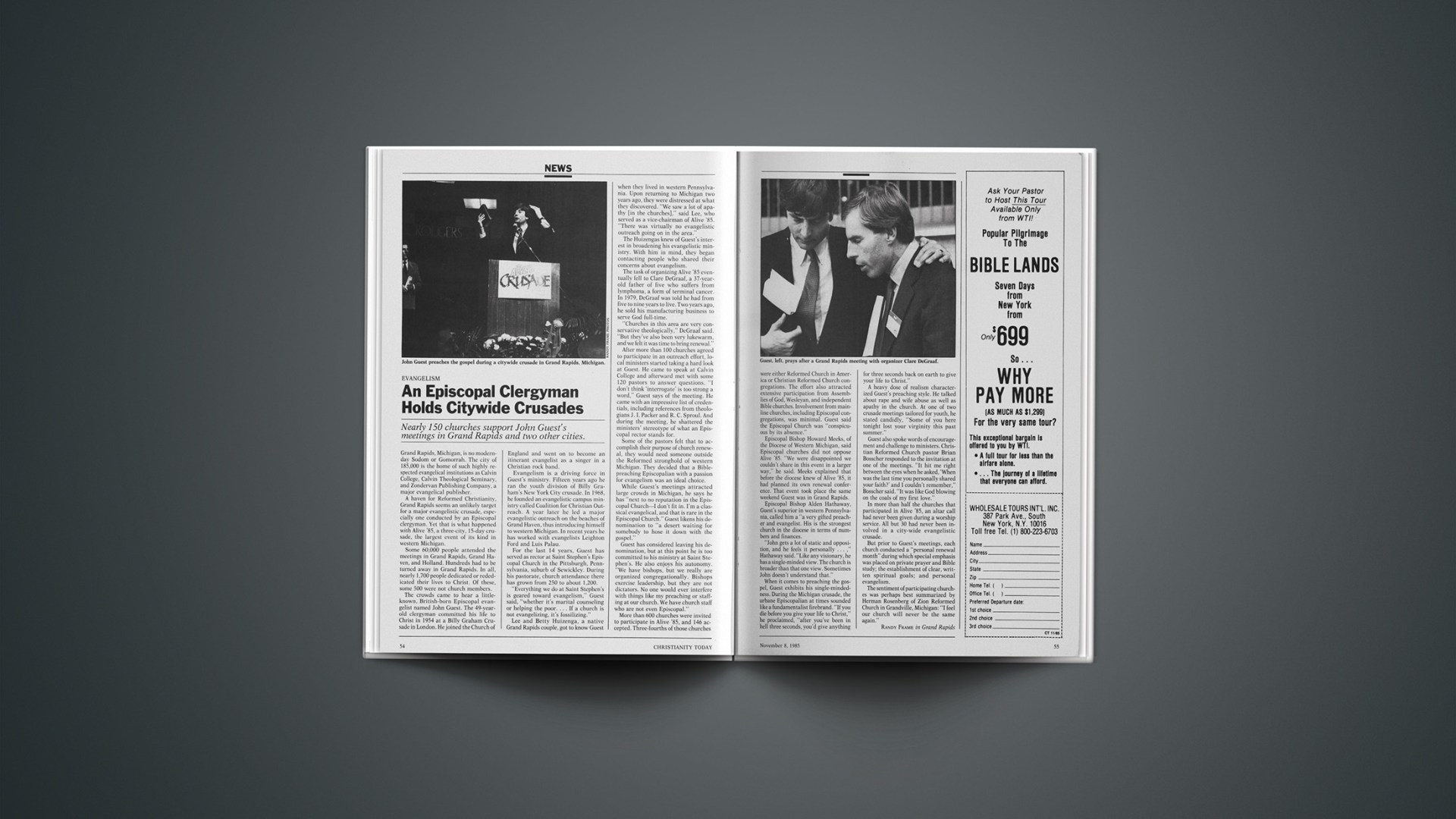

Nearly 150 churches support John Guest’s meetings in Grand Rapids and two other cities.

Grand Rapids, Michigan, is no modern-day Sodom or Gomorrah. The city of 185,000 is the home of such highly respected evangelical institutions as Calvin College, Calvin Theological Seminary, and Zondervan Publishing Company, a major evangelical publisher.

A haven for Reformed Christianity, Grand Rapids seems an unlikely target for a major evangelistic crusade, especially one conducted by an Episcopal clergyman. Yet that is what happened with Alive ’85, a three-city, 15-day crusade, the largest event of its kind in western Michigan.

Some 60,000 people attended the meetings in Grand Rapids, Grand Haven, and Holland. Hundreds had to be turned away in Grand Rapids. In all, nearly 1,700 people dedicated or rededicated their lives to Christ. Of these, some 500 were not church members.

The crowds came to hear a little-known, British-born Episcopal evangelist named John Guest. The 49-year-old clergyman committed his life to Christ in 1954 at a Billy Graham Crusade in London. He joined the Church of England and went on to become an itinerant evangelist as a singer in a Christian rock band.

Evangelism is a driving force in Guest’s ministry. Fifteen years ago he ran the youth division of Billy Graham’s New York City crusade. In 1968, he founded an evangelistic campus ministry called Coalition for Christian Outreach. A year later he led a major evangelistic outreach on the beaches of Grand Haven, thus introducing himself to western Michigan. In recent years he has worked with evangelists Leighton Ford and Luis Palau.

For the last 14 years, Guest has served as rector at Saint Stephen’s Episcopal Church in the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, suburb of Sewickley. During his pastorate, church attendance there has grown from 250 to about 1,200.

“Everything we do at Saint Stephen’s is geared toward evangelism,” Guest said, “whether it’s marital counseling or helping the poor.… If a church is not evangelizing, it’s fossilizing.”

Lee and Betty Huizenga, a native Grand Rapids couple, got to know Guest when they lived in western Pennsylvania. Upon returning to Michigan two years ago, they were distressed at what they discovered. “We saw a lot of apathy [in the churches],” said Lee, who served as a vice-chairman of Alive ’85. “There was virtually no evangelistic outreach going on in the area.”

The Huizengas knew of Guest’s interest in broadening his evangelistic ministry. With him in mind, they began contacting people who shared their concerns about evangelism.

The task of organizing Alive ’85 eventually fell to Clare DeGraaf, a 37-year-old father of five who suffers from lymphoma, a form of terminal cancer. In 1979, DeGraaf was told he had from five to nine years to live. Two years ago, he sold his manufacturing business to serve God full-time.

“Churches in this area are very conservative theologically,” DeGraaf said. “But they’ve also been very lukewarm, and we felt it was time to bring renewal.”

After more than 100 churches agreed to participate in an outreach effort, local ministers started taking a hard look at Guest. He came to speak at Calvin College and afterward met with some 120 pastors to answer questions. “I don’t think ‘interrogate’ is too strong a word,” Guest says of the meeting. He came with an impressive list of credentials, including references from theologians J. I. Packer and R. C. Sproul. And during the meeting, he shattered the ministers’ stereotype of what an Episcopal rector stands for.

Some of the pastors felt that to accomplish their purpose of church renewal, they would need someone outside the Reformed stronghold of western Michigan. They decided that a Bible-preaching Episcopalian with a passion for evangelism was an ideal choice.

While Guest’s meetings attracted large crowds in Michigan, he says he has “next to no reputation in the Episcopal Church—I don’t fit in. I’m a classical evangelical, and that is rare in the Episcopal Church.” Guest likens his denomination to “a desert waiting for somebody to hose it down with the gospel.”

Guest has considered leaving his denomination, but at this point he is too committed to his ministry at Saint Stephen’s. He also enjoys his autonomy. “We have bishops, but we really are organized congregationally. Bishops exercise leadership, but they are not dictators. No one would ever interfere with things like my preaching or staffing at our church. We have church staff who are not even Episcopal.”

More than 600 churches were invited to participate in Alive ’85, and 146 accepted. Three-fourths of those churches were either Reformed Church in America or Christian Reformed Church congregations. The effort also attracted extensive participation from Assemblies of God, Wesleyan, and independent Bible churches. Involvement from mainline churches, including Episcopal congregations, was minimal. Guest said the Episcopal Church was “conspicuous by its absence.”

Episcopal Bishop Howard Meeks, of the Diocese of Western Michigan, said Episcopal churches did not oppose Alive ’85. “We were disappointed we couldn’t share in this event in a larger way,” he said. Meeks explained that before the diocese knew of Alive ’85, it had planned its own renewal conference. That event took place the same weekend Guest was in Grand Rapids.

Episcopal Bishop Alden Hathaway, Guest’s superior in western Pennsylvania, called him a “a very gifted preacher and evangelist. His is the strongest church in the diocese in terms of numbers and finances.

“John gets a lot of static and opposition, and he feels it personally …,” Hathaway said. “Like any visionary, he has a single-minded view. The church is broader than that one view. Sometimes John doesn’t understand that.”

When it comes to preaching the gospel, Guest exhibits his single-mindedness. During the Michigan crusade, the urbane Episcopalian at times sounded like a fundamentalist firebrand. “If you die before you give your life to Christ,” he proclaimed, “after you’ve been in hell three seconds, you’d give anything for three seconds back on earth to give your life to Christ.”

A heavy dose of realism characterized Guest’s preaching style. He talked about rape and wife abuse as well as apathy in the church. At one of two crusade meetings tailored for youth, he stated candidly, “Some of you here tonight lost your virginity this past summer.”

Guest also spoke words of encouragement and challenge to ministers. Christian Reformed Church pastor Brian Bosscher responded to the invitation at one of the meetings. “It hit me right between the eyes when he asked, ‘When was the last time you personally shared your faith?’ and I couldn’t remember,” Bosscher said. “It was like God blowing on the coals of my first love.”

In more than half the churches that participated in Alive ’85, an altar call had never been given during a worship service. All but 30 had never been involved in a city-wide evangelistic crusade.

But prior to Guest’s meetings, each church conducted a “personal renewal month” during which special emphasis was placed on private prayer and Bible study; the establishment of clear, written spiritual goals; and personal evangelism.

The sentiment of participating churches was perhaps best summarized by Herman Rosenberg of Zion Reformed Church in Grandville, Michigan: “I feel our church will never be the same again.”

RANDY FRAMEin Grand Rapids

NORTH AMERICAN SCENE

RAJNEESHPURAM

To Be, or Not to Be?

After Oregon’s attorney general filed a lawsuit alleging violations of the separation of church and state, Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh announced that his commune is not religious. The commune, known as Rajneeshpuram, is incorporated as a town.

“I am against all religions because they have done only harm to mankind,” Rajneesh told reporters. “… For the first time in the history of mankind, a religion has died.”

Attorney General Dave Frohnmayer remained unconvinced, however. “A religion does not cease to be because its leader says so,” he said. “It’s the acts and the practices that are important. The bhagwan appears to be holding up an egg and calling it a sausage.”

A few weeks earlier, several of Rajneesh’s top aides—including his personal secretary, Ma Anand Sheela—left the country. Rajneesh accused the former aides of driving his commune into debt, poisoning salad bars in a nearby town, and attempting to poison two public officials. Sheela has called the allegations—which the state is investigating—“total nonsense.” She said she left the commune because she was tired of working 20 hours a day on Rajneesh’s behalf.

WITCHCRAFT

Senate Denies Tax Break

The U.S. Senate voted to take away tax-exempt status from any group that promotes witchcraft or satanism. Sen. Jesse Helms (R-N.C.) proposed the measure, which was adopted without objection on a voice vote.

The action was taken on an amendment to the Treasury, Postal Service and General Appropriations Act. The amendment defines satanism as “the worship of Satan or the powers of evil.” Witchcraft is defined as “the use of sorcery or the use of supernatural powers with malicious intent.”

“We allow tax-exempt status for bona fide religious organizations because we believe they help promote the common good,” Helms said. “Cults and witchcraft groups do not. In fact, they lead to violent and unlawful behavior.”

A Senate-House conference committee will decide whether to retain Helms’s amendment in the appropriations bill. A similar measure was introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives by Rep. Robert S. Walker (R-Pa.).

CHICAGO

Birth Control in School

Chicago religious leaders are divided over a program that provides public high school students with birth control devices.

The Pro-Life Action League and Moral Majority have picketed DuSable High School, where the program is located. Critics say the program is “giving promiscuity an implicit stamp of approval.” Cardinal Joseph Bernardin joined the opposition, saying, “There is good reason to doubt that more and better contraceptive information and services will make major inroads in the number of teenage pregnancies.”

The program is supported by William A. Johnson, a Baptist minister and former president of the Church Federation of Greater Chicago. He argues that a school birth-control program in St. Paul led to a drop in birthrates among school-age girls from 70 per 1,000 in 1973 to 26 per 1,000 today.

COURT ORDER

Falwell to Pay $5,000

A Sacramento, California, Municipal Court judge ruled that Moral Majority leader Jerry Falwell owes $5,000 to Jerry Sloan, a homosexual who proved that Falwell verbally attacked Sloan’s church.

In July 1984, Falwell denied making an attack on the Universal Fellowship of Metropolitan Community Churches. He offered Sloan $5,000 to produce a tape recording that would prove he had made such an attack.

Judge Michael Ullman ruled that Sloan proved that Falwell had attacked the church. Sloan presented a tape of a March 1984 sermon Falwell preached on his “Old Time Gospel Hour” program. Ullman said Falwell referred to the Metropolitan Community Churches as “brute beasts, part of a vile and satanic system.” The judge ordered Falwell to pay court costs and honor his $5,000 offer to Sloan. Falwell’s attorneys have appealed the decision.

“RIGHT TO DIE”

Suit Fails in Ohio

An Ohio man has failed to prove that an Akron physician violated a patient’s “right to die.”

In 1980, Gifford Leach asked Dr. Howard Shapiro to disconnect a respirator from Leach’s terminally ill wife, Edna Marie Leach. Shapiro refused, and Gifford Leach obtained a court’s permission to disconnect the respirator. Shapiro and other Akron doctors still refused to comply. Mrs. Leach died in 1981 after an out-of-town physician disconnected the life-support machine.

Gifford Leach sued Shapiro for compensation for emotional pain. But Judge John Reece found insufficient evidence to award such damages.

OKLAHOMA

Smith Resigns Pastorate

Bailey Smith, former president of the Southern Baptist Convention, has resigned his pastorate to enter full-time evangelism. Smith had pastored the First Southern Baptist Church of Del City, Oklahoma, since 1973.

Two years ago, Smith was said to be receiving as many as 200 requests per day asking him to speak at a revival or other special event. At that time, Smith and John McKay, a former singer with the James Robison Evangelistic Team, formed the Real Evangelism association. At first, Smith limited the meetings to 12 Sunday-through-Wednesday revivals per year. He later reduced the number to 8 per year.

During a recent city-wide crusade in Tulsa, Oklahoma, the Real Evangelism team received a “love offering” of $43,592. Garnet Cole, missions director for the Tulsa Baptist Association, described the offering as a record.