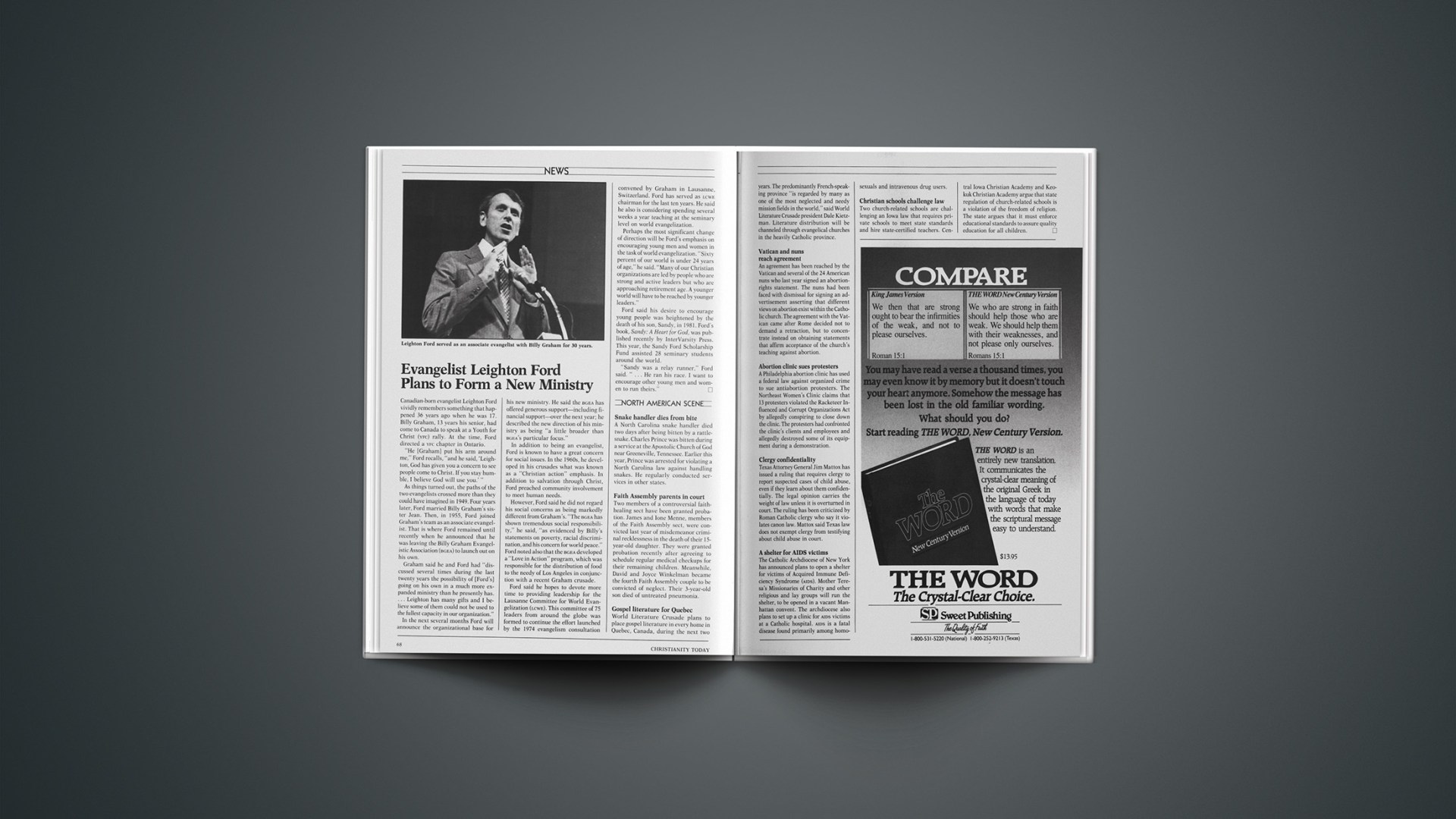

Canadian-born evangelist Leighton Ford vividly remembers something that happened 36 years ago when he was 17. Billy Graham, 13 years his senior, had come to Canada to speak at a Youth for Christ (YFC) rally. At the time, Ford directed a YFC chapter in Ontario.

“He [Graham] put his arm around me,” Ford recalls, “and he said, ‘Leighton, God has given you a concern to see people come to Christ. If you stay humble, I believe God will use you.’ ”

As things turned out, the paths of the two evangelists crossed more than they could have imagined in 1949. Four years later, Ford married Billy Graham’s sister Jean. Then, in 1955, Ford joined Graham’s team as an associate evangelist. That is where Ford remained until recently when he announced that he was leaving the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association (BGEA) to launch out on his own.

Graham said he and Ford had “discussed several times during the last twenty years the possibility of [Ford’s] going on his own in a much more expanded ministry than he presently has.… Leighton has many gifts and I believe some of them could not be used to the fullest capacity in our organization.”

In the next several months Ford will announce the organizational base for his new ministry. He said the BGEA has offered generous support—including financial support—over the next year; he described the new direction of his ministry as being “a little broader than BGEA’s particular focus.”

In addition to being an evangelist, Ford is known to have a great concern for social issues. In the 1960s, he developed in his crusades what was known as a “Christian action” emphasis. In addition to salvation through Christ, Ford preached community involvement to meet human needs.

However, Ford said he did not regard his social concerns as being markedly different from Graham’s. “The BGEA has shown tremendous social responsibility,” he said, “as evidenced by Billy’s statements on poverty, racial discrimination, and his concern for world peace.” Ford noted also that the BGEA developed a “Love in Action” program, which was responsible for the distribution of food to the needy of Los Angeles in conjunction with a recent Graham crusade.

Ford said he hopes to devote more time to providing leadership for the Lausanne Committee for World Evangelization (LCWE). This committee of 75 leaders from around the globe was formed to continue the effort launched by the 1974 evangelism consultation convened by Graham in Lausanne, Switzerland. Ford has served as LCWE chairman for the last ten years. He said he also is considering spending several weeks a year teaching at the seminary level on world evangelization.

Perhaps the most significant change of direction will be Ford’s emphasis on encouraging young men and women in the task of world evangelization. “Sixty percent of our world is under 24 years of age,” he said. “Many of our Christian organizations are led by people who are strong and active leaders but who are approaching retirement age. A younger world will have to be reached by younger leaders.”

Ford said his desire to encourage young people was heightened by the death of his son, Sandy, in 1981. Ford’s book, Sandy: A Heart for God, was published recently by InterVarsity Press. This year, the Sandy Ford Scholarship Fund assisted 28 seminary students around the world.

“Sandy was a relay runner,” Ford said. “… He ran his race. I want to encourage other young men and women to run theirs.”

NORTH AMERICAN SCENE

Snake Handler Dies From Bite

A North Carolina snake handler died two days after being bitten by a rattlesnake. Charles Prince was bitten during a service at the Apostolic Church of God near Greeneville, Tennessee. Earlier this year, Prince was arrested for violating a North Carolina law against handling snakes. He regularly conducted services in other states.

Faith Assembly Parents In Court

Two members of a controversial faith-healing sect have been granted probation. James and Ione Menne, members of the Faith Assembly sect, were convicted last year of misdemeanor criminal recklessness in the death of their 15-year-old daughter. They were granted probation recently after agreeing to schedule regular medical checkups for their remaining children. Meanwhile, David and Joyce Winkelman became the fourth Faith Assembly couple to be convicted of neglect. Their 3-year-old son died of untreated pneumonia.

Gospel Literature For Quebec

World Literature Crusade plans to place gospel literature in every home in Quebec, Canada, during the next two years. The predominantly French-speaking province “is regarded by many as one of the most neglected and needy mission fields in the world,” said World Literature Crusade president Dale Kietzman. Literature distribution will be channeled through evangelical churches in the heavily Catholic province.

Vatican And Nuns Reach Agreement

An agreement has been reached by the Vatican and several of the 24 American nuns who last year signed an abortion-rights statement. The nuns had been faced with dismissal for signing an advertisement asserting that different views on abortion exist within the Catholic church. The agreement with the Vatican came after Rome decided not to demand a retraction, but to concentrate instead on obtaining statements that affirm acceptance of the church’s teaching against abortion.

Abortion Clinic Sues Protesters

A Philadelphia abortion clinic has used a federal law against organized crime to sue antiabortion protesters. The Northeast Women’s Clinic claims that 13 protesters violated the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act by allegedly conspiring to close down the clinic. The protesters had confronted the clinic’s clients and employees and allegedly destroyed some of its equipment during a demonstration.

Clergy Confidentiality

Texas Attorney General Jim Mattox has issued a ruling that requires clergy to report suspected cases of child abuse, even if they learn about them confidentially. The legal opinion carries the weight of law unless it is overturned in court. The ruling has been criticized by Roman Catholic clergy who say it violates canon law. Mattox said Texas law does not exempt clergy from testifying about child abuse in court.

A Shelter For Aids Victims

The Catholic Archdiocese of New York has announced plans to open a shelter for victims of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS). Mother Teresa’s Missionaries of Charity and other religious and lay groups will run the shelter, to be opened in a vacant Manhattan convent. The archdiocese also plans to set up a clinic for AIDS victims at a Catholic hospital. AIDS is a fatal disease found primarily among homosexuals and intravenous drug users.

Christian Schools Challenge Law

Two church-related schools are challenging an Iowa law that requires private schools to meet state standards and hire state-certified teachers. Central Iowa Christian Academy and Keokuk Christian Academy argue that state regulation of church-related schools is a violation of the freedom of religion. The state argues that it must enforce educational standards to assure quality education for all children.