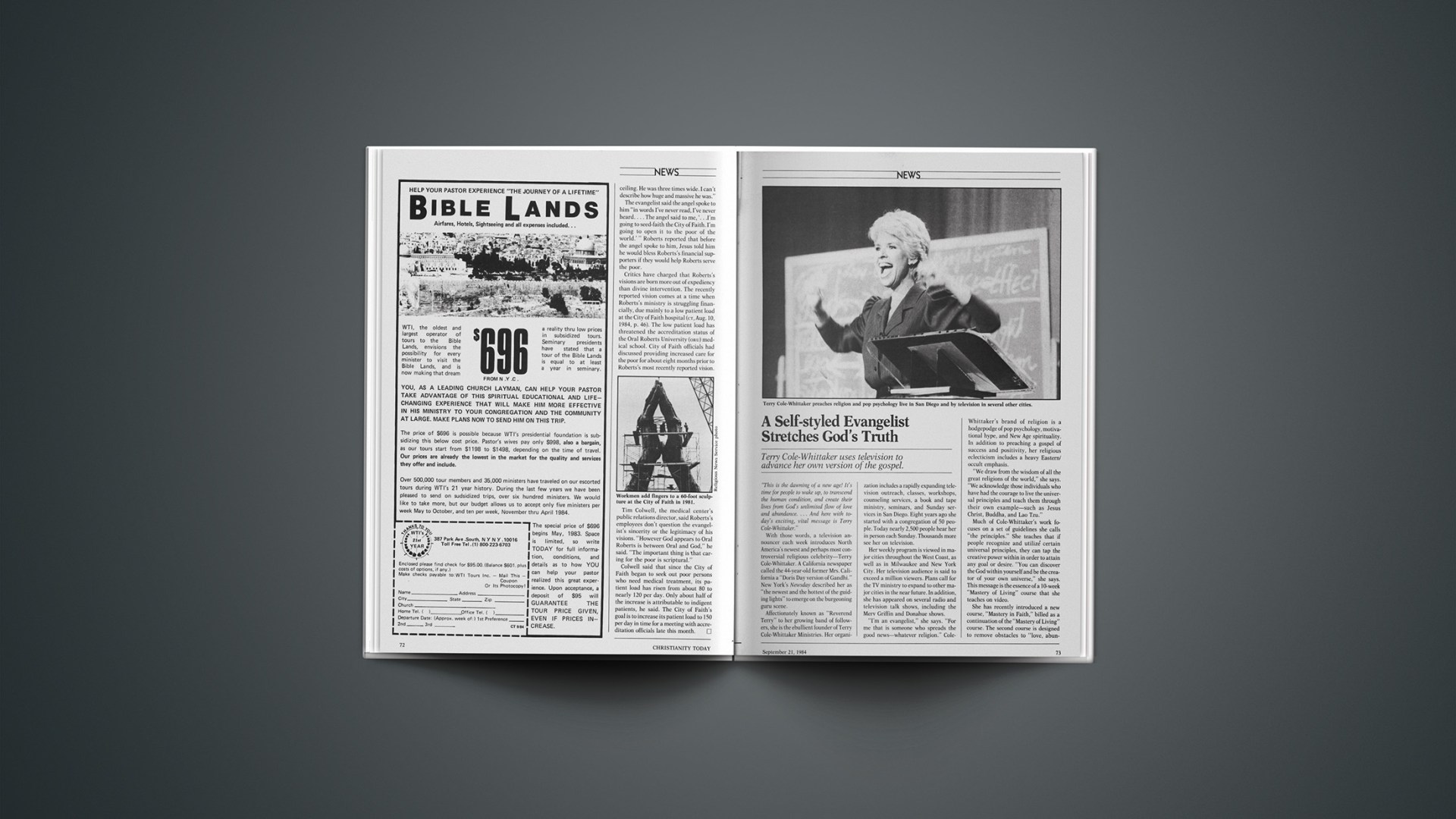

Terry Cole-Whittaker uses television to advance her own version of the gospel.

“This is the dawning of a new age! It’s time for people to wake up, to transcend the human condition, and create their lives from God’s unlimited flow of love and abundance.… And here with today’s exciting, vital message is Terry Cole-Whittaker.”

With those words, a television announcer each week introduces North America’s newest and perhaps most controversial religious celebrity—Terry Cole-Whittaker. A California newspaper called the 44-year-old former Mrs. California a “Doris Day version of Gandhi.” New York’s Newsday described her as “the newest and the hottest of the guiding lights” to emerge on the burgeoning guru scene.

Affectionately known as “Reverend Terry” to her growing band of followers, she is the ebullient founder of Terry Cole-Whittaker Ministries. Her organization includes a rapidly expanding television outreach, classes, workshops, counseling services, a book and tape ministry, seminars, and Sunday services in San Diego. Eight years ago she started with a congregation of 50 people. Today nearly 2,500 people hear her in person each Sunday. Thousands more see her on television.

Her weekly program is viewed in major cities throughout the West Coast, as well as in Milwaukee and New York City. Her television audience is said to exceed a million viewers. Plans call for the TV ministry to expand to other major cities in the near future. In addition, she has appeared on several radio and television talk shows, including the Merv Griffin and Donahue shows.

“I’m an evangelist,” she says. “For me that is someone who spreads the good news—whatever religion.” Cole-Whittaker’s brand of religion is a hodgepodge of pop psychology, motivational hype, and New Age spirituality. In addition to preaching a gospel of success and positivity, her religious eclecticism includes a heavy Eastern/occult emphasis.

“We draw from the wisdom of all the great religions of the world,” she says. “We acknowledge those individuals who have had the courage to live the universal principles and teach them through their own example—such as Jesus Christ, Buddha, and Lao Tzu.”

Much of Cole-Whittaker’s work focuses on a set of guidelines she calls “the principles.” She teaches that if people recognize and utilizé certain universal principles, they can tap the creative power within in order to attain any goal or desire. “You can discover the God within yourself and be the creator of your own universe,” she says. This message is the essence of a 10-week “Mastery of Living” course that she teaches on video.

She has recently introduced a new course, “Mastery in Faith,” billed as a continuation of the “Mastery of Living” course. The second course is designed to remove obstacles to “love, abundance, and limitlessness” so that participants can be “empowered to live as spirit in sonship with God.” Cole-Whittaker says this involves the rejection of scarcity and the acceptance of abundance as a divine right.

Prosperity, success, and abundance are recurring themes in motivational talks given by the New Age evangelist. In a universe filled with abundance, Cole-Whittaker says, “the only one who denies yourself anything is you. Nothing is impossible to you.”

The same ideas can be found in her recent best-selling book, How to Have More in a Have-Not World (Rawson). “You can have exactly what you want, when you want it, all the time,” she writes. “You don’t need to take a vow of poverty to achieve spirituality. Affluence is your right.”

For a donation of $25 or more, the ministry will send a contributor a “prosperity kit” consisting of a cassette tape, a booklet, and a bumper sticker. The kit promises to “enhance one’s awareness of abundance.”

Questions about her own prosperity have given rise to controversy. Los Angeles Magazine alleged that Cole-Whittaker and her fourth husband—they have since divorced—received $20,000 a month plus expenses. She says the information is inaccurate and that it was provided by a disgruntled former employee. It has also been reported that her ministry took in between $5 million and $6 million last year.

The person who has had perhaps the greatest theological impact on Cole-Whittaker is Ernest Holmes, founder of the Religious Science movement and author of The Science of Mind. Religious Science teaches a monistic philosophy that all is One and that people can experience their oneness with God through a form of faith—positive thinking. The ultimate truth, according to Science of Mind, is that man is divine.

Cole-Whittaker studied at the Religious Science School of Ministry and was ordained in 1975. She began her ministry with a congregation of 50 in La Jolla, California. Within months, membership rose to 750 and then to 1,000. As attendance continued to rise, services were held at several temporary locations in the San Diego area. Today, two Sunday morning services are held at the El Cortez Convention Centre in downtown San Diego with a combined attendance of more than 2,000. Last Easter, an estimated 4,000 people were present.

In September 1982 she left the United Church of Religious Science to become the founder of the Science of Mind Church International and to serve as a minister of its only affiliate member, called the La Jolla Church. Most services at the church are upbeat and unconventional. The atmosphere is California casual with a lot of hugging, clapping, and swaying with the music. The order of service includes such congregational songs as “Day by Day” from the musical Godspell, as well as “Accentuate the Positive” and “On the Sunny Side of the Street.” The choir’s selections are equally nontraditional, such as the pop songs “What a Feeling” and “You Are So Beautiful.” A typical service includes elements of a motivational seminar, a Jimmy Swaggert rally, and a Robert Schuller spectacle all rolled into one.

“Her services aren’t dry,” says Harold Bloomfeld, a member of Cole-Whittaker’s ministry board and a well-known advocate of Transcendental Meditation. “She teaches you that it’s okay to have a good time when you’re with God.”

Her sermons are upbeat, reassuring, and nonthreatening. At the La Jolla Church there is no talk of sin, guilt, or eternal damnation. “God loves me, and God would never send me to hell, because it doesn’t exist,” she tells her parishioners. For Cole-Whittaker, hell is a state of mind, and human fallenness is an outmoded concept. “I don’t get that everybody’s lost, because everybody gets to make it. Heaven is a cinch.”

Cole-Whittaker teaches that traditional religion and dogmatic belief systems limit and constrict people. But despite her disdain for traditional religion, including Christianity, she is careful to retain some of its trappings. She maintains a flavor of conventional religion with her references to “the prayer ministry,” “love offerings,” and midweek services.

The self-styled evangelist sounds like a born-again Christian when she states emphatically that “Jesus of Nazareth is my savior.” She claims to be his disciple, and says his “presence … saved my life.” She says she prays to Jesus. “And I always ask, ‘What am I supposed to teach?’ And I always get the message, ‘keep doing what you’re doing, it’s working.’ ”

It is not difficult for a discerning Christian to conclude that the Jesus she refers to is not the Jesus of the Bible. She believes that Jesus was a gnostic. While she claims to be influenced by his teachings, she says she is equally indebted to Holmes, Werner Erhard (founder of est), and A Course in Miracles, which proclaims a distinctly gnostic and metaphysical gospel.

Like most sect leaders, she quotes the Bible selectively and as a means to achieve legitimacy by association. Although she is fond of quoting Jesus, she does not claim that he is the all-powerful, divine, sinless Son of God.

If her organization’s ambitious plans for expansion are realized, chances are good that many more Americans will be hearing Terry Cole-Whittaker’s version of the gospel during the coming months. “I consider myself a spokesman for the spirituality of the New Age,” she says. “My job is to tell people they are the son[s] of God.”