Choice Books: September 7, 1984

Somewhat surprisingly, Mel and Norma Gabler, evangelical Christians who have gained national recognition for their efforts in textbook monitoring (including being featured on “60 Minutes”), credit feminists with the greatest success in changing texts over the past ten years. In 1975 alone, the National Organization for Women obtained 1,651 generic alterations in elementary spellers and math books for Texas, alterations such as changing “mother will bake a cake” to “father will bake a cake.”

However, the Gablers—and others within the conservative camp—are equally quick to point out that their own efforts represent the “silent” 75 percent or more of all Americans who, according to pollster George Gallup, hold to traditional moral values. “It is the publishers and educational bureaucrats who are out of line with the beliefs of the majority,” Mel Gabler says.

Statewide efforts directed toward getting publishers “back in line” understandably have had the most far-reaching impact on text makeup and selection. According to a 1980 survey on censorship practices sponsored by the Association of American Publishers (AAP), the American Library Association (ALA), and the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD), the statewide adoption of textbooks and other institutional materials in 22 of the 50 states is of great importance not only because it directly affects the range of educational materials used in the “adoption” states themselves, but also because it exerts a powerful influence on the materials that will be available in the 28 “open” states.

Heavily populated states such as Texas and Califormia have, as major purchasers of textbooks, the economic power to influence text development. School publishers will usually respond to such pressures out of economic necessity—though often reluctantly. Thus an edition prepared for Texas and California, the two largest adoption states, often becomes the sole edition available nationwide.

Partly because they wield their influence in Texas, the Gablers are regarded as two of the most powerful people in education today. Their book reviews have turned the annual Austin textbook hearing into “a litmus test of how liberal a textbook can be,” according to publisher Fred McDougal.

The extent of the Gablers’ influence (clearly identified as significant by the AAP-ALA-ASCD survey respondents) can be seen in a series of textbook guidelines adopted partially as a result of the work of their Educational Research Analysts group. The six most pertinent guidelines require textbooks to:

• “contain no material of a partisan or sectarian character”;

• present “factual information accurately and objectively without opinionated statements or biased editorial judgments by the authors”;

• “promote the free enterprise system, respect authority and individual rights, and not encourage civil disorder, social strife, or law breaking. Balanced and factual treatment of contrasting points of view in political and social movements is necessary. Violence must be restricted to the context of its cause and consequence”;

• “not include blatantly offensive language or illustrations”;

• clearly distinquish theories “from fact … in an objective educational manner” (This provision was substituted in April for a previous rule stating that “the presentation of the theory of evolution shall be done in a manner which is not detrimental to other theories of origin.” Texas attorney general Jim Maddox had declared the old rule an unconstitutional intrusion of religion into state matters.);

• “treat divergent groups fairly without stereotyping.” To counter radical feminism, books must include “traditional and contemporary roles of men, women, boys, and girls.”

Books that fail to meet any of these guidelines stand in danger of being rejected or, at the very least, sent back to the publisher for rewriting. Such a decision usually has national ramifications, with most sales representatives agreeing that books flunking Texas are generally much harder to sell anywhere else.

Negativism and violence in basic and supplementary readers stirred much of the clamor in West Virginia. A year later (1975) in Texas, Norma Gabler and fellow petitioner Fran Robinson held up in the textbook hearings two Scott, Foresman series for elementary children (Signposts and Milestones, 1975), marked with scores of red tabs indicating episodes of death, violence, suicide, and killing. To these and other objections, publishers typically responded that such incidents were in the Bible. Norma Gabler replied that this was a “sorry defense which tells something about the moral perception of educational change agents. The Bible stresses that these acts are wrong and tells what is right.”

The cry against violence and negativism continued in Texas until officials advised publishers that such books would be rejected in the future. When readers were again presented, the Gablers called them “the greatest change in textbooks since we began our work.”

Richard Carroll, president of Allyn & Bacon, concedes that the publishers got the message. “We now consider it an editorial mistake to have a violent episode in a reader,” he says.

Whereas objections relating to explicit language and sexuality were most often cited as the issues prompting challenges at the local level, the AAP-ALA-ASCD survey referred to earlier reports that statewide challenges more frequently focused on ideological concerns. The issues most often cited were: secular humanism, Darwinism and evolution, scientific theories, criticism of U.S. history, values clarification, undermining of traditional family, atheistic and agnostic views, antitraditional/antiestablishment views, negative or pessimistic views, and moral relativism or situation ethics.

In each of these areas, conservatives admit they are bucking well-established trends and philosophies—yet not entirely without some noteworthy successes, as the following examples illustrate.

Biology: Adam or Ape? The creationist-evolutionist controversy unquestionably draws the sharpest lines of demarcation between the traditionalists and “progressives.” While evolution was slow in coming to textbooks after the Scopes trial in 1925, scientific creationism has been entirely avoided. Yet, according to Gerald Skoog, professor of education at Texas Tech, creationists exert “an influence that has been persuasive and, in some cases, dramatic” (Science News, Jan. 28, 1984).

To prove his point, Skoog points to the fact that Holt, Reinhart & Winston reduced the number of words relating to evolution in Modern Biology, the country’s best-selling biology textbook, from 18,211 in 1973 to 12,807 in 1981; and that the 20,346 words about evolution in a 1974 Silver Burdett book were reduced to 4,314 in the firm’s 1981 edition (Discover, Jan. 1984). Moreover, Laidlaw Brothers’ high school text, Experiences in Biology, does not contain the word “evolution” at all.

Skoog, who has researched the coverage of evolution in over 100 biology texts dating back to the turn of the century, says, however, that evolutionists may be in the process of making a dramatic classroom comeback.

“There appears to be a growing tendency for honesty on the part of publishers,” Skoog says, reflecting his own view of evolution. His initial readings of the 1985 editions of both Modern Biology and Experiences in Biology seem to indicate a substantial increase in the treatment of evolution, with the Laidlaw text devoting an entire chapter to it.

History: The Way We Were? Neal Frey, a former history teacher at Christian Heritage College, expresses the viewpoint of the majority of conservative protesters regarding most history textbooks. “The books,” he says, “still show American history as nothing more than a combination of existential and environmental determinism; and just ignore the Christian origin of our country. They also continue to speak more favorably of communism than our system.”

As an example of faulty methodology and bias, Frey points to Random House’s Freedom and Crisis (Second Edition, 1974, 1978). “This book focuses on a single event against a period in history. For instance, the entire Puritan era is examined in the light of the Salem witch trials with obvious religious bias.”

Protesters have had intermittent success in working “a proper perspective” into U.S. history. Enthusiasm for federalism (where a union of states recognizes the sovereignty of a central authority while retaining certain residual powers of government) has been curbed, as has the lavish praise given the concept of a world government.

Glowing accounts of Marxism have also been curbed. Example: The bald statement in Allyn and Bacon’s A Global History of Man (1970), “The Marxism [in China] turns the people toward a future of unlimited promise, an escalator to the stars,” was qualified by the preface, “Communist leaders say …” (p. 444).

“The imbalance is not as great in the texts we see today,” says Mel Gabler, “but it is still obvious.”

Human Behavior: Values Clarification. More a methodology than a course, values clarification became the sine qua non of progressive education in the 1970s. As formulated by Sidney B. Simon and others, VC embraced both situation ethics and cultural relativism. It posited no fixed values and gave full authority to the student in determining his or her own values system.

VC was soon instituted into everything from social studies to sex education, from early grades through high school. And objectors complained that the new methodology did away with moral absolutes and parental authority. Their protestations torpedoed or forced revisions in a number of books incorporating a VC approach to discussions of drug use and sexual practice. Some examples:

• Random House’s Life and Health (3rd edition, 1976, 1980) for ninth and tenth grades, was withdrawn from the Texas adoption process by the publisher in 1983 after the Gablers cited objectionable passages on sex and death that included: “Adolescent petting is an important opportunity to learn about sexual responses and to obtain sexual and emotional gratification without a serious commitment” (p. 161); “In many societies, premarital intercourse is expected and serves a useful role in the selection of a spouse. In such societies, there are seldom negative psychological consequences” (p. 161); and “The thought of death sometimes occurs in a sexual context … in that the event of orgasm, like the event of dying, involves a surrender to the involuntary and the unknown” (p. 486).

• Another book in this genre failed to get a single vote from the Texas Textbook Commission. Charles A. Bennett’s Finding My Way (1979), for ninth graders, used the word “masturbation” 43 times in a two-and-a-half-page, mostly favorable discussion of the practice.

• Also in 1983, 25 health books were postponed for adoption until warnings about illegal drugs were balanced with cautions against legal substances. This came about after the Gablers noted that one book, Laidlaw’s Good Health for You (1983), devoted several pages to the ill effects of coffee, tea, and over-the-counter prescriptions, while only 19 lines were spent describing the harmful effects of marijuana.

In spite of these successes, conservatives are not fooling themselves into thinking they have stemmed the tide of humanist influence. One problem is that the conservative protest movement is, in fact, a nonmovement. There is no nationwide conspiracy on the part of religious fanatics to establish a kingdom of innocence in public schoolrooms, and individual efforts on the local level usually come to an abrupt end once the issue at hand is addressed.

“The number of parents involved is directly proportionate to the number of offensive, stupid or misleading things in the classroom,” says Onalee McGraw, an education consultant and currently a member, by Presidential appointment, of the National Council on Educational Research.

Trying to assist concerned parents in the process of influencing their local schoolboards are groups like the American Education Coalition. Founded in 1983, AEC provides parents with a series of topical ACTION kits geared to effecting conservative change. One recent kit offered individuals a “how to” approach to getting elected to the school board. Still another described the problems inherent in current sex education curricula.

Marcella Donavan, the director of the AEC, says the overall objective of such “helps” is to sensitize parents to the problems in education and to their role in doing something about them. “We’re here to help parents improve their schools,” Donavan says, “and to show them how their views can find their rightful place in the marketplace of ideas.”

As for the Gablers, their impact on that marketplace has been nothing short of phenomenal. Yet their “organization” is but a handful of committed individuals working long hours with a minimum of support. And at this time, there is no other couple or committee on the horizon ready to work alongside or even further their efforts.

The lack of any cohesive organization may be the least of conservative worries, however. Conservative protesters, for example, have most often been characterized as “censors” and book burners, while their liberal counterparts are perceived as freedom fighters. Moreover, mass media portrayals of textbook protests have furthered the myth that only the Right is critical of classroom texts. The public relations problems inherent in these multiple misconceptions are obvious, with many conservatives caricatured as outdated traditionalists living in a Victorian time warp. To this charge Mel Gabler simply responds that “the books were stripped of God and moral values before they ever came to us.”

A deeper problem still is the fact that mainstream America does not appear to grasp what the fight is all about. That ideologies are conflicting in the classroom is still foreign to most parents. According to Judith Krug, director of the American Library Association Office of Intellectual Freedom, the majority of Americans see today’s textbooks as apparently—and adequately—“fulfilling [educational] needs.”

So what of the future? Can opposed value systems be reconciled and satisfied in school texts?

Mel Gabler worries that a politically powerful National Education Association (NEA), backed by a supportive president and Congress, could establish a virtual dictatorship over curriculum in public schools. A worst-case scenario would be a standardized, federally financed curriculum, administered and written by progressive educators, and forced upon both public and private schools by federal and state educational bureaucracies.

A harbinger of such a curriculum, he says, could be the NEA’s recently introduced junior-high pilot program on nuclear disarmament and extremism in America. The Washington Post editorialized that the NEA offering is hardly objective (it says the U.S. is far ahead of the Soviets in nuclear arms) and amounts to “political indoctrination.”

Of greater concern to Gabler is the apathy and ignorance of Americans about the new textbooks and their power. He quotes D. C. Heath, a textbook publishing pioneer, as saying, in effect, “Let me write the textbooks of a nation and I care not whose songs it sings, or writes its law.”

JAMES HEFLEY AND HAROLD SMITH

When school doors opened ten years ago in the quiet of Kanawha County, West Virgina, few could have anticipated the incendiary war of words that left lives threatened and students on extended vacation. At issue was a list of supplementary readings that traditional conservatives characterized as too violent and suggestive. To the self-professed “freedom fighters” who branded such attacks as narrow-minded, the controversy was nothing less than a knockdown, drag-out fight for free thought, free press, and free speech.

Peace was eventually restored. But the controversies over what Johnny reads rage on in local school boards and textbook adoption hearings across the country.

Today, the protest “movement” numbers among its participants men and women from both ends of the sociopolitical spectrum. Yet it is the conservative or “New Right” group that has drawn the greatest attention and criticism from public educators. Its so-called censorship activities have become a popular theme among press and professionals alike; and its impact, however understated or ridiculed, is real.

But whether or not conservatives have been successful in reversing—or even slowing—what they perceive to be a secularist trend in textbooks remains open to serious debate.

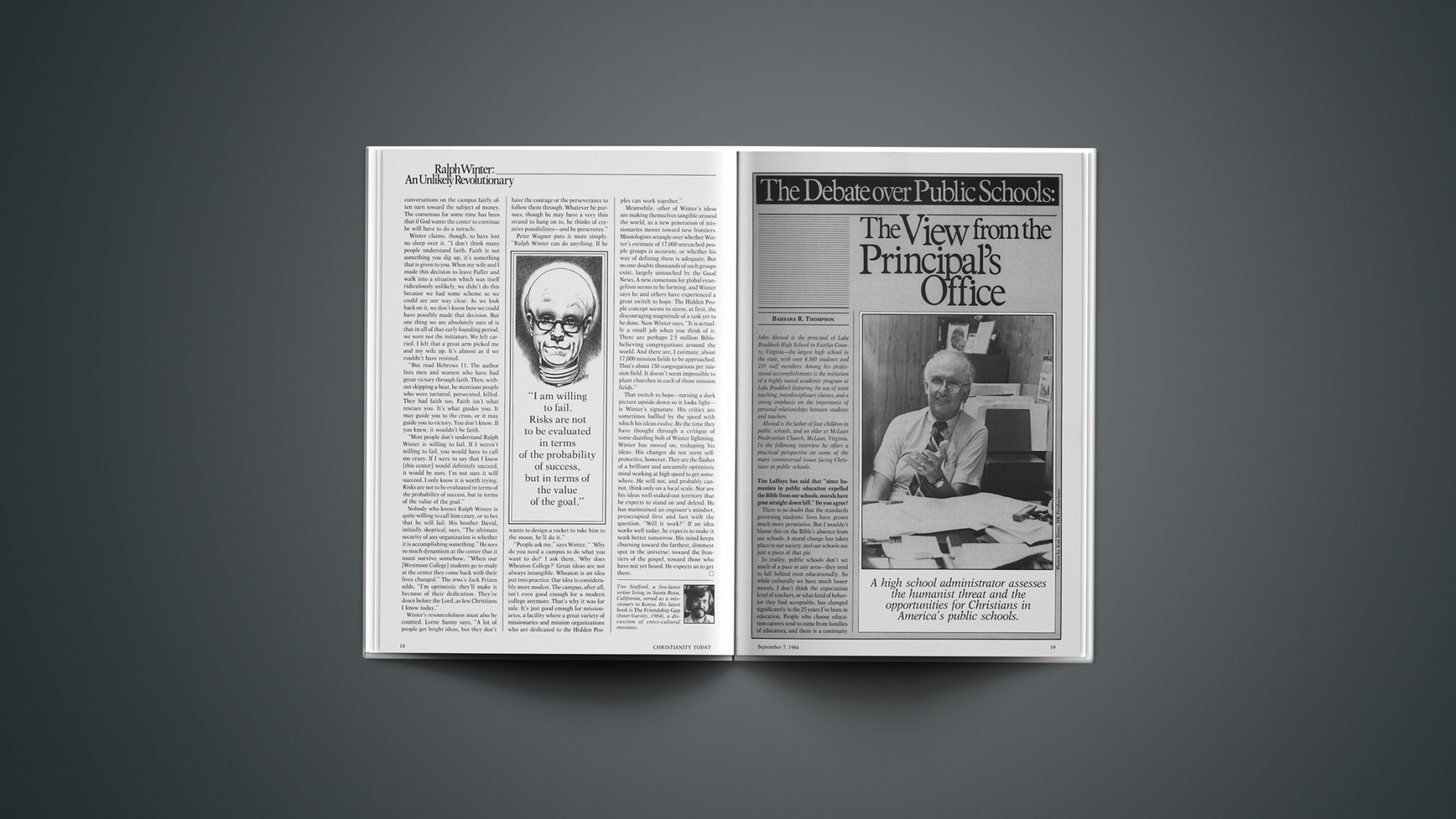

John Alwood is the principal of Lake Braddock High School in Fairfax County, Virginia—the largest high school in the state, with over 4,300 students and 235 staff members. Among his professional accomplishments is the initiation of a highly touted academic program at Lake Braddock featuring the use of team teaching, interdisciplinary classes, and a strong emphasis on the importance of personal relationships between students and teachers.

Alwood is the father of four children in public schools, and an elder at McLean Presbyterian Church, McLean, Virginia. In the following interview he offers a practical perspective on some of the many controversial issues facing Christians in public schools.

Tim LaHaye has said that “since humanists in public education expelled the Bible from our schools, morals have gone straight down hill.” Do you agree?

There is no doubt that the standards governing students’ lives have grown much more permissive. But I wouldn’t blame this on the Bible’s absence from our schools. A moral change has taken place in our society, and our schools are just a piece of that pie.

In reality, public schools don’t set much of a pace in any area—they tend to fall behind even educationally. So while culturally we have much looser morals, I don’t think the expectation level of teachers, or what kind of behavior they find acceptable, has changed significantly in the 25 years I’ve been in education. People who choose education careers tend to come from families of educators, and there is a continuity of moral feeling. While some people want to make the school a fall guy for students’ behavior, it is closer to the truth to see the schools suffering from, and attempting to combat, a moral deterioration in society.

Do you think public schools should play a primary role in upholding moral values?

I would like to think they should play a key role. Boys and girls spend a lot of time in school, and there is opportunity to make a significant impact on their lives. As Christian educators, we can communicate to students that they are special people—created in God’s image—and that they ought to be proud of that fact. We can encourage our fellow staff members to practice and communicate basic values, such as truthfulness and honesty. Sometimes we tend to think these values are taught by punishing their opposites, and that often has to be done. But students learn from consistency. If their principal, their teachers, and their counselors are all demanding honesty, they themselves will buy into it as one of the good things in life.

Many conservative Christians see the public schools as a philosophical battleground pitting secular humanist thought against our Judeo-Christian heritage. Is this a fair assessment of what’s going on?

If there is a battle going on, there are a lot of schools where no one knows it. And maybe that’s the New Right’s concern. They see a subtle but conscious undermining of Christian values.

What teachers see, however, is a classroom full of students who aren’t interested in anything. So, for instance, to get a class interested in a writing unit, a teacher might have the students write a horoscope. When the assignment gets home to Christian parents (and even non-Christian parents), there is justifiably a strong reaction. Those in the New Right might even sense a conspiracy—that the teacher has a hidden motive for using this particular unit.

The teacher does have a hidden motive—he wants to teach the kids to write. While there might be a few teachers who are consciously committed to secular humanism as the salvation of their students’ lives, most of them are simply trying to generate interest in any direction they can find it.

Are there parameters within which teachers operate when determining the proper ways of generating student interest?

Of course. And when it comes to such potentially volatile subjects as, for example, horoscopes, we as a school staff try to determine an appropriate course of action with the students’ best interests in mind.

Have the efforts of the New Right had a discernible effect on the practice or policies of the public schools?

It has made us more sensitive to curriculum problems, and to the effects certain texts and exercises are having on our students. At the same time, there is a sense in which the New Right doesn’t want public schools: it wants Christian schools. Tim LaHaye has argued that the schools could at least adopt the last six commandments. There really is no controversy over those commandments. But there are a lot of battles and a lot of scars with respect to texts and language and sex education. Public schools wrestle with how to meet the needs of special interest groups and still address issues.

Do you find that non-Christians involved in education tend to identify evangelical Christianity with the New Right?

There is no doubt that this happens. For example, the New Right makes the statement that when sex education came into public schools, morals went down the drain. But there were all kinds of things going on in life with a minimum of sex education. That just isn’t a very palatable conclusion to propose without substantial data. With that kind of thinking in the air, a lot of people who are otherwise receptive to the Christian faith begin to say, “This just doesn’t hold water.” They turn off completely because the credibility level is so low. It makes it very difficult for other Christians to make an impact.

One of the most troubling results of all this negative publicity is that Christian teachers in public schools are becoming reluctant to share their faith with students. Other teachers don’t think twice about giving their views in the classroom, whether they be political or philosophical. That’s as it should be; every person in a public school, including the teacher, has a right to share his or her opinion and perspective.

Somehow Christian teachers, the ones most intent on proclaiming the gospel to please their Lord, feel trapped and silenced by their mistaken impression that it is illegal to talk about their religious beliefs. Even when I encourage my own Christian teachers to be more vocal about their spiritual commitment, they get nervous and tell me they will get in trouble for speaking frankly. The truth is, unless a teacher gets on a soapbox and becomes dogmatic, he or she is perfectly free to say, “This is my perspective as a Christian. These are the beliefs I hold, and this is how I arrived at them.”

There are a lot of subjects, like history and literature, that can’t be studied without examining religious beliefs. In this context, I find that non-Christian teachers often talk more freely and accurately about the Christian faith than Christian teachers, who fear they will be accused of violating the separation of church and state. It is the students who are shortchanged by this silence. If the Christian viewpoint is the only one they never hear, they get a one-sided picture of what life is all about.

As a Christian public school administrator, how do you handle differences of opinion about value-laden and controversial subjects like biology?

First of all, we have to accept the fact that when a subject is taught, the perspective of the teacher will be there. That being the case, it is important to make sure the teacher is not presenting just his or her own perspective.

For instance, a teacher might feel so strongly about Darwin’s theory of evolution that he teaches it as a fact. That’s not giving the kids a fair shake. They need to know what the options are; they need to hear, “Now look at the possibility of creation. Isn’t that just as plausible?”

More recently, we’ve moved into creation science—which isn’t faring too well in the courts. I think that is too bad. But again, if I were a teacher, I would want to make sure that even if my students accepted God as Creator, they wouldn’t feel forced to buy into a package that included, for example, an Earth 10,000 years old. There are many ways God could have created the world, and there is no consensus among Christians as to how he went about it. Teachers shouldn’t be locked into saying, “This is the way it was.” Instead, they should be free to present the whole spectrum of problems and possibilities. If there isn’t a God, where did everything come from? And if there is a God, then there are any number of ways he might have created the universe. Maybe it was a “Big Bang.” The point is that everything we say at this time is theory and needs to be presented that way.

What do you think parents should do if they discover their children are getting a viewpoint they disagree with presented dogmatically in the classroom?

I think they should stand up and holler. If the teacher is not being fair in the presentation, that needs to be corrected. And if materials are objectionable, there are options. The purpose of an English assignment, for instance, is usually broad-based, and any number of novels could meet that purpose.

I don’t think you could eliminate every book that someone wants eliminated. I myself am quite prudish and don’t want to use books with much at all that is questionable. Then I go home and turn on the television and wonder if I am crazy. I won’t come close to letting those kinds of things be discussed in class, and yet students are home watching them every night.

Can you give us an example of a textbook controversy you were involved with?

The first year I came to Fairfax County a Christian parent took me to task for letting a teacher use Brave New World. The teacher, in turn, asked me if I had read the book—a fair question for a teacher to ask her principal! I took the book home, read it, and found it fascinating. I couldn’t find anything wrong with the way the teacher was presenting the material, and met with the parents to tell them so.

I eventually ended up on a Christian radio show discussing the matter with a local minister. He asked me a stream of belligerent questions: “What have you to say, Mr. Alwood, about line 7 on page so-and-so?” The line would be a string of swear words that had nothing to do with the course of the book. Our entire discussion was futile, and a good example of what we as Christians do to each other when we take a “do’s-and-don’ts” approach to our faith. There are no easy answers for these troublesome and complicated issues. We need to work them through with genuine love and respect for one another.

But how do you balance the demands of intellectual freedom with the need to protect students from constant bombardment by the seamier elements of life?

It’s not easy. In general, I believe the more you know, the better decisions you can make. I don’t try to limit the presentation of information, nor the freedom with which something can be discussed. Now, if it is a question of a risqué approach versus an intellectual one, that would give me concern. When we can find good, solid materials with little if anything “alluring” in them, then let’s use them.

What role do you think the community, and the church as part of the community, should play in the approval of textbooks?

The schools belong to the people, and over the years I’ve tended to think they should, therefore, have a great deal of influence in making these decisions. I no longer feel that way. Most community groups have narrow interests and carry a particular banner. When it is time to make decisions about budgets and textbooks, or whether to offer sex education and psychology, there aren’t many broad-based groups around.

There is still room for sound Christian input into the school curriculum, but, unfortunately, we don’t get it. We’ve been given material by Christian groups on Ronald Reagan that claimed, among other things, that Reagan is the redeemer of our nation. You throw that at a group of history teachers and they aren’t going to buy it. And if it bothers me as a Christian, just think what it does to them!

At the same time, all kinds of good material coming from Christian authors is being neglected. Why isn’t someone encouraging the schools to use the works of C. S. Lewis or Francis Schaeffer? There is a danger that in reaction to the extremism of the New Right, some very good Christian material will be thrown out as well. The New Right won’t be prepared to defend these worthwhile authors; and evangelicals, because they aren’t involved, won’t even know what is happening.

How do you feel about sex education in the public schools?

The real question is what is the school’s role in handling something many consider a nonschool problem? Schools are here to teach, some would say, and sex education is none of their business.

But what school is all about is the lives of kids; and an important part of their lives concerns what is happening to them sexually. I’ve found families have a hard time dealing with sex, and I’m not sure but what the Christian community isn’t the worst of all.

My own position is that the schools need to provide enough information to make conversation comfortable between kids and parents, and then they can take it from there. If we just leave the subject cold, or ignore it completely, I’m not sure who we are helping.

Jesus chastised the religious leaders of his day for concentrating on minor points of the law while neglecting weightier matters. Do you think the Christian community is in danger of making the same mistake with respect to public schools?

Yes. The prayer-in-school issue is an example. About nine years ago I heard that our state had passed a law requiring a moment of silence so students could pray. We did this for a week, and then I checked around to see how it was going. It wasn’t one of the great moments in our school, perhaps because our size prevented the personal dimension that is needed. In any case, it wasn’t working arid I didn’t want to do it anymore. I was relieved when I found out it wasn’t required in the first place and that I wasn’t legally bound to do something I knew was ineffective.

The point is that we sometimes do things for the sake of doing them when, in fact, they are meaningless. At faculty meetings prior to the school year, I usually do quite a bit with Scripture and prayer. But I have to be careful that I don’t become just someone doing something to be seen, rather than someone doing something because it has spiritual meaning.

What positive issues could Christians focus their energies on?

Right now school boards are being pushed to the wall with respect to what organizations they will allow in the school; many Christian groups, like Young Life and Fellowship of Christian Athletes, are being targeted. The situation is getting bad, and I don’t think it is legally necessary. As Christians, we need to make sure that the kinds of people we want relating to our kids are allowed in the schools.

I once had a parent call me to complain that her daughter was meeting a Young Life staff person twice a week to talk over what’s right and wrong in sex relationships between boys and girls. I told the mother she was lucky to have someone willing to spend time with her daughter, giving her a straight perspective on what was good for her. We should be thankful when these kinds of people befriend our children.

If we are going to keep these Christian groups in the schools, some compromises have to be made. The Church of the Latter Day Saints, for example, has had a strong morning program for years with good moral content for students. I may not accept their theology, but I do accept their right to be in school.

How do you decide who is allowed in a public school and who isn’t?

The standard question is: “If someone wanted to form a club for fascists, would you let them?” I’d answer no. This is a judgment that a principal has to make in light of what kinds of people he wants associating with students. If there were people whom I felt shouldn’t be allowed in school and, as a result, I had to keep other needed groups out, then I would keep both out. But the Christian community should be working to make sure this dilemma does not arise.

But sometimes teachers and parents seem to be in an adversarial relationship. How should we as Christians work to affect change?

By involving ourselves with the normal parent groups. Parent-teacher problems escalate when we separate ourselves and form splinter groups that are usually perceived as targeting teachers.

What’s your perspective on the Christian school movement?

I have no ill feelings toward parents who send their kids to private or Christian schools. I am disturbed, however, by people in the Christian community who have ill feelings toward Christian parents who send their children to public schools.

To be perfectly honest, if I were flying from Washington to Miami, I wouldn’t be overly concerned about whether my pilot was a Christian or not. My concern would be can he fly the plane. I feel the same way about education. You do kids a disservice by not giving them the best education they can get to go with the Christian training they receive at home.

Unfortunately, most parents I’ve known have moved their children to private schools not because of curriculum considerations but because they want their children under tighter supervision. In other words, they want someone watching their children carefully. I can’t promise that in our school. In fact, that’s something we don’t even try to do.

It is a matter of faith for me as a parent of children in public school that the Lord is in control. If others think their kids need tighter boundaries, that’s a judgment they have to make. But I think behavior problems are the poorest reasons for sending a child to Christian school. We are fooling ourselves if we think kids are much different in the two schools. Kids are kids. They have the same fears and the same problems wherever they are.

As an educator and a parent, what kind of response have you had to your witness for Christ in the public school?

It is easy to wonder how much of an impact you have on people. One encouraging thing that came out of the hostage crisis1In November of 1982, Dr. Alwood and eight other school employees were held hostage for 21 hours by an armed, former student trying to negotiate a meeting with his girlfriend. All of the hostages were eventually released unharmed. Dr. Alwood stayed with the student until he surrendered himself to the police. for my wife and me was a new appreciation for how many people have gotten the message that God is real to us. One of my fellow hostages said, “You had something I didn’t. I saw that whatever the outcome, you could accept it.” My wife and I, she on the outside waiting and I on the inside, heard this over and over again. We were able to share with people how this “something” was available to everyone.

I think my relationship with Jamie, the gunman, during the time I was held hostage, is an example of the kind of forum a public school can be. If anyone thought that we spent 21 hours talking about the Lord, or that I had my Bible open the entire time, they would have been mistaken. It became apparent quite early that Jamie had some wacky theological ideas, and that pursuing spiritual issues with him might have meant a potential mental upset. Instead, we talked about his school days, which had been a pleasant experience for him.

Yet our time together was used mightily by the Lord. Christians all over Washington who knew that I was a Christian and that Jamie’s mother was also a Christian came together to pray for us. I was amazed at the number of Christian teachers who called me up afterwards to say, “I know where you stand, and I want you to know that I’m a Christian too.”

I came away knowing that God’s message doesn’t have to be preached from a pulpit to be heard.

Tim Stafford is a free-lance writer living in Santa Rosa, California. He is a distinguished contributor to several magazines. His latest book is Do You Sometimes Feel Like a Nobody? (Zondervan, 1980).

When Ralph Winter was a student at Princeton Theological Seminary, someone pointed out that the chapel was 200 years old. “Oh, well,” he replied, “in California when a building is 20 years old we tear it down and build a better one.” His remark went all over the seminary campus as an example of what to expect from Californians with no respect for culture or tradition.

Thirty years later Winter, now a balding, respected expert on missions, still scandalizes with his penchant for irreverence. Practically everyone, pro or con, concedes that he is a genius whose original thinking has stirred up the world of missions. But he draws strong reactions. Some revere him as a visionary, three steps ahead of the church. Others see him as an impractical agitator. One prominent Christian leader observes, “Ideas come out of his mind a mile a minute. Ninety-nine out of 100 will not work. One is a good one. But that place [the U.S. Center for World Mission] is a mess. There’s no sense of order.”

Yet Peter Wagner of the Fuller School of World Mission thinks history will record Winter as one of the half-dozen men who did most to affect world evangelism in this century. And Jack Frizen, executive director of the Interdenominational Foreign Missions Association (IFMA), believes we are seeing a turning point in world missions, the greatest move since the period after World War II: “The Lord is using Ralph to stir up a new generation.”

James Reapsome, editor of the Evangelical Missions Quarterly, cites two major mission revolutions since the sixties, both of which are more closely identified with Ralph Winter than with any other individual. “What might be called the ‘unreached people groups’ strategy,” writes Reapsome, “has shaken the missions community to the core.”

Those who study missions engage in earnest debate over Winter’s ideas and statistics, and sometimes shake their heads over his methods. But no one ignores him. His ideas have set the agenda for missions in this generation.

Winter has brought to the minds and consciences of evangelical Christians the hidden or unreached peoples—that huge number who now have little chance to hear the gospel, let alone respond. Though most Americans still view missions as a dull subject, missions leaders feel the stirrings of new excitement, especially among young people. The success of Inter-Varsity’s Urbana missionary convention is only the most visible sign. New organizations are springing up, research is proliferating, new methods and approaches are being tried, and a whole new generation of young people—many from secular universities—is applying to go out. Third World countries, too, have been establishing mission boards and sending out missionaries. The attention of evangelical mission boards has shifted toward new horizons, “frontier missions.” While continuing to help churches founded a century ago, nearly all evangelical missions are once again actively setting their sights beyond, toward those people groups that have no church.

Wherever you poke your finger in all this, you find Ralph Winter. Winter will not accept the common belief that a church can put so many resources into world mission that it neglects its home soil. He believes there can be no genuine renewal without a renewal of the church’s ultimate concerns. That means following Jesus to seek the lost, leaving the 99 sheep to seek the single lamb. “Unless and until, in faith, the future of the world becomes more important than the future of the church, the church has no future.”

He sees the U.S. Center for World Mission, the Pasadena conglomerate he founded and tirelessly boosts, as a lever to help tip the whole Christian world over the edge: a huge evangelistic snowball gathering momentum and size. At that point, Winter claims, he only wants to be along for the ride. “I would rather be ahead of something that is happening, than the head of something that once happened.”

One expects a charismatic, riveting figure, a man to mesmerize crowds. Ralph Winter is instead a bookish, mild-mannered professor who wears neat coats and ties he salvages from the missionary storeroom at Lake Avenue Congregational Church in Pasadena, where he grew up and still attends. Until recently, he and his wife drove two of the oldest moving automobiles in Southern California. (Their new, three-year-old car is a mixed blessing, Winter says, “Now we have to lock it.”) His speaking style is offhand and professorial; and while it rivets some, it puts many ordinary people to sleep.

He is perennially optimistic, spinning off new schemes. “He can give you more ideas on his lunch hour than you can implement in a year,” says Lorne Sanny, head of the Navigators and an old Winter friend. Winter also has a peculiar power for gathering almost fanatical disciples. With no money and a negligible constituency behind it, his organization holds, tenuously, a piece of property where about 40 different mission-related organizations—the majority of which he had a hand in starting—have offices. This is the U.S. Center for World Missions, dedicated to stirring up other people and organizations to reach the hidden peoples.

The center occupies a former college campus on several blocks of a quiet residential district in the Pasadena hills. It is a striking place to visit, with an atmosphere that is part school, part corporation, part revival. About 300 people live and work there, nearly all having raised their own financial support to live at a common missionary level. Most are recently out of college or seminary, without experience, but with a great deal of idealism, commitment, and, in many cases, intellectual brilliance. (There are, for instance, quite a number of computer wizards recently from Cal Tech.) A sprinkling of gray heads, mainly retired missionaries, have come to help. Middle-aged veterans—“those who have something to lose,” Winter says—are few.

The center has little central administration since Winter prefers to start an organization, get it moving, and turn it loose to run on its own. He thinks many small groups, loosely linked, have more dynamism than one large dinosaur. “If people don’t want to function together,” Winter says, “it doesn’t matter whether they are under your administration or not.” Most of the organizations have no legal tie to the U.S. Center, yet they are clearly part of the movement, and they meet regularly for prayer, discussion, and problem solving. You hear excited talk about corners of the world you never heard of before—the Maldive Islands, for instance—and terms such as “unimax people” or “redemptive analogies.” The center buzzes with energy and with what can only be called evangelical fervor.

Perhaps most startling of all, considering that in September of next year they face an $8.5 million payment on the college campus, the center has no fund-raising office. Every individual, from Ralph Winter down, spends up to an hour in a back room each morning opening and responding to mail from a particular zip code area of the U.S. Winter says they have never written a letter to someone who did not write to them first. Furthermore, by principle, they never ask anyone for more than a one-time $15.95 gift. By this means, they reckon, they will have to reach about a million people to secure the property. Last year, facing a $6 million payment, they put their hopes on a sort of chain letter. It raised only $1 million, and they slid into an interest penalty that requires them to make much higher quarterly payments. This time, facing an even bigger payment, they are hoping a chain of home parties will do the trick.

Something is happening in Pasadena, something unlike anything else in the evangelical world. It is not yet quite clear what it will prove to be: whether a passing wave of youthful enthusiasm, or the beginning of a movement that will change the direction of the Christian church.

Winter is a quintessential Californian, proven by the fact that his father was one of the chief planners for the Southern California freeway system. Winter does not belong to the Southern California of hot tubs and Johnny Carson, but to a California symbolized by the crew-cut ingenuity of Cal Tech. Southern California itself is a wild idea—seven million suburbanites clinging to the sides of mountains and drinking water piped from Arizona. It has bred a number of people, Winter among them, who think that anything is possible.

Winter is also a product of the strong, creative Southern California evangelical subculture, which has been growing steadily since World War II. More mission organizations, Winter says, are now headquartered in the Los Angeles area than in any other place in the world. Winter’s parents were Presbyterians, but more loyal to the Christian Endeavor movement, an early parachurch group that helped establish the modern “youth group.” Through a CE meeting Winter made a serious Christian commitment.

When their church decided to drop CE, the Winter family moved to Lake Avenue Congregational Church. There Winter encountered the Navigators, and their all-or-nothing style of discipleship helped shape him. Dawson Trotman, six blocks from his home, became a mentor. Lorne Sanny led the high school Bible club that sometimes met in the Winter home, where Ralph still lives. Sanny remembers Winter “then as today … an idea man, and not the ideas that ordinary people would think.” Winter’s brother David, now president of Westmont College, remembers ideas discussed avidly around the dinner table. “Ralph was deeply curious about life. He was an experimenter, an inventor. He was constantly making something work better than it did—homemade firecrackers, for instance, which practically killed him. He always had a better way to do it. There was hardly anything he didn’t think he could improve.”

Winter studied engineering at Cal Tech and graduated while in navy pilot training during World War II. After the war he began ten years as a professional, peripatetic student. He attended or taught at Westmont College, Princeton Seminary, Fuller Seminary, Pasadena (Nazarene) College, Prairie Bible Institute, Columbia University, and Cornell University. He ended with an M.A. from Columbia, a Ph.D. from Cornell (in anthropology and linguistics), and an M.Div. from Princeton. He refers to that period as his years of “wilderness wandering,” when he groped for a sense of direction. He developed a reputation as a troublemaker, always willing to take up a position others thought irreverent.

While at Fuller, for instance, he concluded that, in view of the crushing needs of the world, it was wrong to spend money on neckties. The conviction grew on him that he could not honor the Lord while wearing a necktie—to the point where one night he telephoned his elderly, saintly pastor to inform him that he would not be able to read Scripture the next morning in church. When his reason came out—these were the 1950s—the pastor was aghast, and argued with Winter over the phone for an hour. Finally the pastor insisted that Winter read Scripture no matter what he wore. He did, in a fatigue jacket. He wore khakis long afterwards, an almost unimaginable wardrobe during those staid years. Only later, when he studied anthropology, did he conclude that he should imitate local customs so that people he spoke to would listen to him. He adopted a dress suit and bow tie, and wore those as religiously as the khakis.

“Navigators plus anthropology was a heady combination,” he says, “because anthropology loosens you up from all human customs and allows you to rethink why you do what you do. Dawson [Trotman] was an anthropologist to the extent that he said, ‘Always ask why you do what you do the way you do it.’ That’s a radical question.”

After graduating from Princeton, Winter and his wife, Roberta, went to Guatemala as United Presbyterian missionaries. The Winters do not approach family life conventionally. Roberta has worked with him side by side on every project of their married life, including seminary’s Hebrew homework. As their four daughters grew up, they joined the team. When the oldest was 12 and the youngest 7, the Winters found it a nuisance to dole out allowances. They solved the problem in a way only Winter would think of: adding their daughters’ signatures to the family checkbook. The bank was aghast, but the Winters never experienced any problems. The four, now in their twenties, three married, have grown into strong Christians, and with their husbands have joined wholeheartedly in the cause of the U.S. Center.

In Guatemala the Winters worked with an Indian tribe, starting schools, small factories, and cooperatives. Most memorably, they joined other missionaries to launch a theological education program that did not require a busy pastor to leave his church to study. This program spread over the world as Theological Education by Extension (TEE), and endures to this day as a significant movement. After ten years in Guatemala, Winter was asked to join the newly formed Fuller School of World Mission. There, for the next ten years, he continued to spread the TEE philosophy and taught the history of missions.

Never content just to teach, Winter remained an activist, helping to launch such organizations as the William Carey Library, which publishes low-cost books on missions, and the American Society of Missiology, a scholarly body. But in the early seventies new ideas began to percolate in his head. Teaching and studying the history of the church fed his naturally big ideas: he looked for the pattern of what God had done in the 4,000 years since Abraham. He began to assemble facts and statistics about the parts of the world where the gospel had penetrated, and where it had not. Others, especially Ed Dayton of World Vision, were thinking along similar lines. But Winter put the whole picture together. He saw a startling, and at first frightening, situation. Not only were most of the world’s people without the gospel, most of them would never get the gospel no matter how fast the church grew. Multiplication was not enough.

The founding idea of the Fuller School of World Mission was Donald McGavran’s observation that Christianity does not usually spread out indiscriminately, like ink in water, but along the lines of cultures and languages. To “jump” from one culture to another is unusual; we should expect “church growth” usually to occur within the boundaries of a particular culture. For instance, a Korean church in Los Angeles will not tend to “grow” in numbers by adding white Anglo-Saxons; it will add fellow Koreans.

Winter simply flipped that idea on its head. If churches normally grow within the boundaries of culture, then a culture that has no church may never be reached by normal church growth. When Winter made rough calculations of which people-groups around the world had churches of their own and which did not, he found that between 75 and 85 percent of the world’s non-Christians had no church whatever within their social and linguistic boundaries, and thus, humanly speaking, no chance to hear the gospel ever—no matter how much the existing church grew and evangelized. They had no Christian neighbor to tell them the news, if you define “neighbor” in terms of culture and language.

The insight crystallized for him in Korea, where he and several members of the Fuller faculty were sleeping on the floor of a retreat center. “I woke up and said something like ‘the special problem I had never seen before was that though there were all these people to reach, we cannot “grow” into them.…’ So Glasser [Arthur Glasser, who teaches the theology of missions at Fuller] said something I’ll never forget, because he put it beautifully. ‘Ralph, what you’re saying is that if every single congregation in the world had a fantastic spiritual explosion, and would reach out to everybody within their social matrix, 80 percent of the world’s non-Christians would be untouched.’ ”

From there it did not take Winter long to redefine the missionary task. Most of what missionaries were doing—and what he himself had done in his ten years as a missionary—involved helping an existing church. Missionary evangelism had been so successful, in effect, that it had obscured the original purpose of missions. Church growth and support was needed, but only if it did not overlook the dramatically more significant task, without which the Great Commission would never be fulfilled. Missionaries must go to people groups with no church at all and establish a beachhead. Once that beachhead is in place, it can grow outward to reach the entire people group. Without a beachhead there is little hope for evangelism.

By 1974, at the Lausanne Congress on World Evangelization, Winter was a plenary speaker on this very subject. The congress was a watershed for many church leaders, forcing them to think about the whole globe, and Winter’s ideas kindled a spark in many minds. He, however, left feeling uncertain he had convinced anyone. “But I had convinced myself,” he says, and from that meeting his life has been preoccupied with the Hidden Peoples. (“Unreached” or “Frontier” peoples are terms for the same thing.)

In fact, the usually slow-moving mission agencies responded with great speed. Within two years the IFMA and EFMA, two leading mission consortiums, had accepted the Hidden Peoples as their first priority. But Winter was frustrated; he felt nothing was happening. In late 1975 a piece of property came to his attention, a vacant college campus in the hills a few miles from Fuller. He had once taught Greek there. He saw in the campus just the facility needed to make things happen. He had no money, no organization to back him. The other Fuller faculty were not ready to try a multi-million-dollar purchase so quickly. But for Winter it was all or nothing. Resigning his tenured position, he went out to raise personal financial support for the first time in his life. He, his wife, and a few loyal individuals launched the U.S. Center for World Missions in a rented portion of the college. They hoped to buy the whole thing. In the campus they saw a chance for the creative ferment that Winter loves. They hoped to start a national revival of missions—to fan the spark into a blaze.

The acquisition of the campus of Pasadena Christian College is a story of cliff-hanging prayer meetings, of large checks arriving at the last moment, of spiritual battles with a Hindu sect that also wanted the campus (and, for a time, shared it with the U.S. Center). So far, nearly $6 million has been paid on the campus. With $8.5 million coming due in a year, the center has very little money in the bank, no mass mailings or TV spots in the works, and no rich uncles (that they know of) waiting to write stupendous checks. Inevitably, conversations on the campus fairly often turn toward the subject of money. The consensus for some time has been that if God wants the center to continue he will have to do a miracle.

Winter claims, though, to have lost no sleep over it. “I don’t think many people understand faith. Faith is not something you dig up, it’s something that is given to you. When my wife and I made this decision to leave Fuller and walk into a situation which was itself ridiculously unlikely, we didn’t do this because we had some scheme so we could see our way clear. As we look back on it, we don’t know how we could have possibly made that decision. But one thing we are absolutely sure of is that in all of that early founding period, we were not the initiators. We felt carried. I felt that a great arm picked me and my wife up. It’s almost as if we couldn’t have resisted.

“But read Hebrews 11. The author lists men and women who have had great victory through faith. Then, without skipping a beat, he mentions people who were tortured, persecuted, killed. They had faith too. Faith isn’t what rescues you. It’s what guides you. It may guide you to the cross, or it may guide you to victory. You don’t know. If you knew, it wouldn’t be faith.

“Most people don’t understand Ralph Winter is willing to fail. If I weren’t willing to fail, you would have to call me crazy. If I were to say that I knew [this center] would definitely succeed, it would be nuts. I’m not sure it will succeed. I only know it is worth trying. Risks are not to be evaluated in terms of the probability of success, but in terms of the value of the goal.”

Nobody who knows Ralph Winter is quite willing to call him crazy, or to bet that he will fail. His brother David, initially skeptical, says, “The ultimate security of any organization is whether it is accomplishing something.” He sees so much dynamism at the center that it must survive somehow. “When our [Westmont College] students go to study at the center they come back with their lives changed.” The IFMA’s Jack Frizen adds, “I’m optimistic they’ll make it because of their dedication. They’re down before the Lord, as few Christians I know today.”

Winter’s resourcefulness must also be counted. Lome Sanny says, “A lot of people get bright ideas, but they don’t have the courage or the perseverance to follow them through. Whatever he pursues, though he may have a very thin strand to hang on to, he thinks of creative possibilities—and he perseveres.” Peter Wagner puts it more simply. “Ralph Winter can do anything. If he wants to design a rocket to take him to the moon, he’ll do it.”

“People ask me,” says Winter, “ ‘Why do you need a campus to do what you want to do?’ I ask them, ‘Why does Wheaton College?’ Great ideas are not always intangible. Wheaton is an idea put into practice. Our idea is considerably more modest. The campus, after all, isn’t even good enough for a modern college anymore. That’s why it was for sale. It’s just good enough for missionaries, a facility where a great variety of missionaries and mission organizations who are dedicated to the Hidden Peoples can work together.”

Meanwhile, other of Winter’s ideas are making themselves tangible around the world, as a new generation of missionaries moves toward new frontiers. Missiologists wrangle over whether Winter’s estimate of 17,000 unreached people groups is accurate, or whether his way of defining them is adequate. But no one doubts thousands of such groups exist, largely untouched by the Good News. A new consensus for global evangelism seems to be forming, and Winter says he and others have experienced a great switch to hope. The Hidden People concept seems to stress, at first, the discouraging magnitude of a task yet to be done. Now Winter says, “It is actually a small job when you think of it. There are perhaps 2.5 million Bible-believing congregations around the world. And there are, I estimate, about 17,000 mission fields to be approached. That’s about 150 congregations per mission field. It doesn’t seem impossible to plant churches in each of those mission fields.”

That switch to hope—turning a dark picture upside-down so it looks light—is Winter’s signature. His critics are sometimes baffled by the speed with which his ideas evolve. By the time they have thought through a critique of some dazzling bolt of Winter lightning, Winter has moved on, reshaping his ideas. His changes do not seem self-protective, however. They are the flashes of a brilliant and uncannily optimistic mind working at high speed to get somewhere. He will not, and probably cannot, think only on a local scale. Nor are his ideas well-staked-out territory that he expects to stand on and defend. He has maintained an engineer’s mindset, preoccupied first and last with the question, “Will it work?” If an idea works well today, he expects to make it work better tomorrow. His mind keeps toward the churning farthest, dimmest spot in the universe: toward the frontiers of the gospel, toward those who have not yet heard. He expects us to get there.

Tim Stafford is a free-lance writer living in Santa Rosa, California. He is a distinguished contributor to several magazines. His latest book is Do You Sometimes Feel Like a Nobody? (Zondervan, 1980).

This month’s Miss America pageant will bring more unwelcome publicity for Vanessa Williams, the incumbent who abdicated under duress after Penthouse magazine published her explicit, degrading sexual poses. Nearly as degrading were those who tried to exonerate Miss Williams, to somehow assign blame to the only parties who acted swiftly and responsibly during the episode, the pageant officials. What she did constituted “moral turpitude,” they concluded. Disgusted, they demanded and received her resignation.

The Penthouse publisher, Bob Guccione, tried to sell the idea that the pageant’s view of wholesomeness was dated and dusty. News commentators of all stripe saw hypocrisy in the pageant executives’ action. Did not the Penthouse poses differ only in degree from the sexual titillation of the swimsuit competition, they asked. All the objections splintered against the determination of the pageant executives to hold firm to their image of what is decent and acceptable in American life.

We congratulate them for standing fast and acting decisively. While we do not necessarily endorse swimsuit competitions, the efforts to compare them with clinically explicit lesbian sex pictures are feeble and ridiculous. There is cause for the pageant executives to consider how much they, like Guccione, use sex to sell their product, but the pornographic Penthouse is worlds away from the beauty and talent pageant in Atlantic City.

Miss Williams was exploited and perhaps lied to, yet so was Eve. There is always a price to pay for perverting God’s purposes and the beauty of his created order. Miss Williams learned the price quickly. We hope that, sometime, Bob Guccione will learn it also.

TOM MINNERY

When will we recognize that religious freedom is the premier freedom of the Bill of Rights?

In 1644, the English poet John Milton wrote the Areopagetica, an impassioned plea against censorship after the government tried to control some of his earlier published work. In that earlier work Milton had stated his perspectives on biblical faith as against the pompous show of the state church. Milton’s Areopagitica would help ignite revolutionary fires in the American colonies. It contributed to a firmer foundation for the First Amendment freedoms in our own Constitution.

Ironically, that same First Amendment has become a lethal weapon aimed at one of the causes for which Milton stood—the free expression of religious ideals. Today the battle is being fought in the nation’s public school systems. Whether the particular issue is prayer, the posting of the Ten Commandments, or the gathering of students for quiet Bible study, the same tiresome complaint is heard: Because the First Amendment prohibits the establishment of religion, any trace of religion in any public school must be a constitutional trespass. The American Civil Liberties Union has used this convolution (along with its willingness to sue) to bully local school boards into erasing all evidence of religious expression from junior and senior high schools. The usual result has been that voluntary prayer or Bible study groups are refused permission to meet on school property, even though all manner of nonreligious student clubs are active. In a few cases, the decisions have been bizarre:

•The principal of the Lake Worth (Fla.) Community High School stopped the distribution of the 1982–83 yearbook when he discovered an objectionable page. On it was a picture and description of the school’s Bible club and a Scripture passage, John 3:16. The principal ordered his staff to cut out the page with razor blades.

• In the Boulder, Colorado, school district, two or more students cannot sit together for the purpose of religious discussion.

• A teacher in that same district was reprimanded for passing out invitations to a private Christmas party. The error was the use of the word “Christmas.” In Boulder schools, the accepted term is “winter holiday.”

Earlier this year in Washington, D.C., Sen. Jeremiah Denton held hearings on the situation, and speaker after speaker raised questions that carved this irrational state of affairs in bold relief: How is it that high school students can address God profanely in the hallway, but not reverently in the classroom? Why must they pledge allegiance to a nation under God, yet be denied permission to discuss the nature of that God? By what logic can students meet after school to hear the philosophies of Plato, Marx, and Hitler but not Moses, Jesus, and Paul?

The First Amendment to the Constitutions of the United States

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

Thankfully, the nonsense seems to be near its end. Over the summer, first the Senate, and then the House, passed bills (see the article in News) based on the free speech argument. They granted equal access to public school facilities for students who wish to hold religious, philosophical, or political meetings. (The inclusion of the last two categories was a sop to certain senators who begrudged any attention given only to religion, although clearly it has been only religion that has been the subject of discrimination. No one is harassing the Young Democrats or the Aristotelian Society.)

House Speaker Thomas P. O’Neill inspired no one by his strenuous and futile gyrations to kill the bill in the face of overwhelming bipartisan support for it. By the time the bill reached the House, the Senate had already passed it 88 to 11, and in spite of O’Neill’s obstinance, the House passed it 337 to 77. President Reagan’s support made his signature certain.

By the stunning refusal of the American Civil Liberties Union to endorse the bill, even with its clear foundations in the First Amendment right of free speech, the ACLU has proven itself to be what evangelicals have believed for some time: infected by virulent, antireligious prejudice. Its own handbook on student rights is unequivocal in advising high school students that they may exercise free speech rights by protesting, passing out literature, holding rallies, inviting outside speakers, and forming school clubs. The handbook was published to guide students in expressing antiwar sentiment during the Vietnam years of the early seventies. Now in the eighties, when the issue is religious sentiment, the ACLU keeps silent, and thereby speaks volumes about itself.

Those who oppose the equal access bill make one of two arguments. The first is that high school students are immature, too vulnerable to handle religious pressures properly. Yet those who say this are by and large the same ones who champion the right to abortion and contraceptives for these same students without parental consent. (Under the equal access bill, parents may withhold consent for their children to attend religious meetings at school. Under current law, they have no such right in the matter of abortion or contraception.) Additionally, the Supreme Court has ruled clearly that, immature or not, high school students do not leave constitutional rights at the schoolhouse door. We can appreciate that high school students are not mature adults. But the eradication of all religious influence from their high school communities is unnatural. It teaches powerfully that religion is not among the respectable choices in life, and this is an intolerable overreaction to the problem of church-state separation.

The second argument of the opposition is that the bill invites the admission of not only legitimate groups, but every cult and religious aberration. Actually, under the bill school principals retain full control over disruptive influences. But the larger point is that evangelicals do not fear the free marketplace of ideas. The real fear, borne out in tearful history, is that the intolerance of the state, either by its government or its official church, is by far the greater danger. It was John Stuart Mill who said, “Men are not more zealous for truth than they often are for error, and a sufficient application of legal, or even of social penalties will generally succeed in stopping the propagation of either.” Mill noted that the Reformation was put down 20 times before Luther.

We are thankful this bill has passed Congress, and yet we feel a certain dissatisfaction with the state of the matter. The premise of equal access is that by virtue of the First Amendment, extracurricular religious meetings deserve the same considerations given all others. That is true, but it does not end the discussion. Religious freedom is the first of the preferred freedoms in the Bill of Rights, and what that means must be recognized. The country cannot endure without the primacy of Judeo-Christian principle, nor was it meant to. In his farewell address to the young nation, George Washington said, “Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports.” Only when that truth is once again honored will the turmoil over religious freedom cease.

By now you’re probably aware of the latest in spiritual growth tools—the Christian cruise.

At one time, trips to the Holy Land or Reformation sites were the rage. Today it’s not where you go, it’s how you get there. Cruise boats, complete with onboard lecturers and concert artists, don’t go anywhere in particular. Cruise directors downplay geography.

Ads bill them as an Alaskan Getaway, Mexican Riviera Retreat, or Caribbean Odyssey, and the closest they get to a site of theological import is the Bermuda Triangle, which has vague Trinitarian imagery.

Cruises aren’t new—several seafarers are mentioned in the Bible. But now we know they did it all wrong.

Noah’s cruise could have been a romantic retreat with his wife; instead, the whole family came along (not to mention their animal friends).

Jonah let himself get pushed around by the ship’s crew, his cruise ended prematurely, and he never got a refund. All he got was great sermon material.

Paul endured three shipwrecks. Once he had to tread water for an entire day, and another time the captain’s bad judgment forced Paul unexpectedly to spend a whole winter in Malta. He should have signed up for the Mexican Riviera.

The Bible records only one cruise filled exclusively with Christians. But in that one, Jesus was wakened from a sound sleep by passengers complaining about the weather.

Today’s “disciple ships” are such an improvement. Private rooms, swimming pool, life rings stenciled “Rescue the Perishing,” and a friendly crew offering everything from morning coffee to the daily devotional guide, The Cruise Missal.

Strangely, though, Christian VIPs are almost unanimously critical of these frilly flotillas.

“I was disappointed,” said one. “My wife and I had visions of Love Boat, but instead of an all-star cast, all we saw were three seminary profs, two retired pastors, and a writer of Christian romance novels.”

“I thought cruises were great at first,” another admitted. “They were special, unique. But now every preacher I know has gone on one. You tell people you’re a cruise speaker, and they yawn. I’m going back to leading Holy Land tours.”

That’s okay, shipmate. No one ever said discipleship was easy.

EUTYCHUS

Though not a regular reader of CHRISTIANITY TODAY, I chanced to read “Jews Who Believe in Jesus” by Bruce H. Joffe [July 13]. Mr. Joffe makes a number of errors. To refer to people who have accepted Jesus as their Messiah as “Jewish people” is incorrect. The moment one accepts Jesus as Messiah he becomes a Christian. He severs connection with Jewish people just as a Moslem would sever his or her connection with Islam upon acknowledging Jesus to be the greatest of all prophets rather than Mohammed.

The descriptions of the various forms of contemporary Jewish religious life are simplistic and inaccurate. Joffe displays little accurate knowledge of Judaism. Your article on former Jews who have come to believe in Jesus needs to be far more accurate both in title and content. The lack of accuracy is rather offensive.

RABBI HILLEL COHN

San Bernardino, Calif.

I wish to compliment Bruce Joffe for his article. The average Jew knows more about Christianity and Islam than the informed Christian or Moslem knows about Judaism. Judaism is more than just a religion; it is a philosophy, a commitment, and a set of values. Far down on their list of priorities is the belief in the coming of a Messiah and eternal life. Since the “Jews for Jesus” do not reflect Jewish messianism, it is both wrong, and an affront to the Jewish community; therefore, they should not be known as “Jews for Jesus” or “Hebrew-Christians.”

HAROLD M. SPINKA, M.D.

Chicago, Ill.

Bruce Joffe’s article was very insightful. Being a Christian, and coming from a Jewish background, I read it with great interest. Faith must be objective. The object of all mankind’s faith must and will be seen in Jesus Christ (Phil. 2:9–11). I pray that those who sense their roots will be lost if their identity is not preserved will see their wholeness in Jesus Christ. We must not allow our ethnic reality of persons to cloud the superiority of the One to whom we pray, worship, or tell others about. This issue is not new. The early Christians of Jewish identity faced a similar situation.

CHRIS CONE

Dallas, Tex.

In truth, the Hebrew-Christian movement is not nearly as widespread as Joffe would have us believe. A more accurate estimate of the number of Jews involved (frequently Gentiles participate as well) is probably much less than 10,000 nationwide. Furthermore, while Hebrew-Christians crave credibility, both from Christians and Jews, and seek to pass themselves off to unwitting Christians as another Jewish group albeit one that affirms belief in Jesus, this is simply not the case. In fact, both they and their hybrid message are rejected as representing a “fourth branch of Judaism” not only by traditional Jews, but by the entire Jewish community. A more accurate depiction of Jewish attitudes toward Jewish believers in Jesus would be akin to theirs toward cults. Here, however, the Hebrew-Christian movement additionally creates friction and distrust between evangelicals and Jews and has a harmful impact on Christian-Jewish relations. These people are regarded as a front for evangelical and fundamentalist Christians whose sole aim is to wean Jews away from their ancestral faith.

RABBI YECHIEL ECKSTEIN

Holyland Fellowship of Christians & Jews

Chicago, Ill.

CT’s interview with George Will [“The Convictions of America’s Most Respected Newspaper Columnist,” July 13] brought to mind Paul’s comments summarized in 1 Corinthians 1:20, “Where is the wise man? Where is the scholar? Where is the philosopher of this age? Has not God made foolish the wisdom of the world?” Will reflects this worldly wisdom, and reveals that he, as have all other wise men of the world, believes Christianity, indeed, all religious thought, to be a creation of man—merely an expression of longing for something more than food. “That’s why some people go to church,” Will concludes. This is emptiness and darkness, not to mention arrogant and ignorant. What did CT hope to gain? I’ll stick with Paul, who told the world that Jesus and his cross would be foolishness to the wise of the world.

MARK A. SCHARFENAKER

Denver, Colo.

George Will’s admiration for the welfare state demonstrates why we are in such an economic mess. Believing it is fine to forcibly take money from some people to give to other people perverts the role of government and puts Will in a league with the liberals.

Will a conservative? I thought I was a conservative!

GARY BRYSON

Cedar Mountain, N.C.

In his editorials, Kenneth Kantzer is a master at clarifying complex issues and bringing us to a point of consensus. However, “American Civil Religion” [July 13] skips over the difficult questions. He writes that evangelicals may support civil religion provided that America is “under God.” But are we here in the U.S.A. in fact “under God”? He states that “biblical Christians are patriotic.” But if patriotism means that I value the lives, traditions, and well-being of Americans over the rest of humankind, I must opt out.

Finally, what is appropriate for Christians in other lands? Should they have their civil religions too? Or is America somehow a special nation before God?

PATRICK WALL

San Luis Obispo, Calif.

Kantzer’s warm embrace of civil religion in the recent issues of your magazine was rightly accompanied by a warning against idolatry of the state. There is, however, a far more subtle danger. Kantzer points out that civil religion has adopted (however selectively) some of the terms and ideals of Christianity. This being so, the danger lies not so much in our forsaking the one for the other as in confusing the two. We Christians must exercise care not only that we not worship the state, but that we are not duped into hearing evangelical Christianity in the well-chosen platitudes of politicans eager to please. Certainly Presidents have been known to employ this device with astonishing success.

ROBERT J. BAST

Holland, Mich.

This letter is written in response to “United Church of Christ Members Want to End ‘Theological Disarray’ ” [July 13]. Let the facts be straight. The United Church of Christ is not the successor to the Congregational Christian Churches. There are those who believe that the Congregational Christian Churches who chose to participate in the merger that resulted in the formation of the United Church of Christ did so at the sacrifice of Congregational polity, which is the distinguishing characteristic of historic Congregationalism. Over 400 Congregational Christian Churches did not participate in that merger; we are known as the National Association of Congregational Christian Churches of the United States.