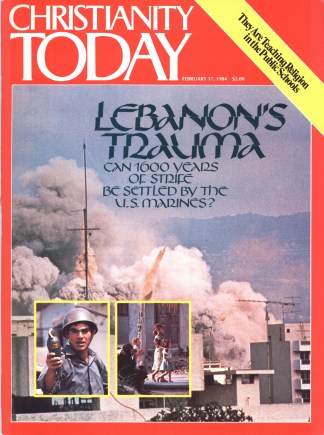

The evangelists make an impact on a country where only 14 percent of the people attend church.

England has a rich Christian history. The modern missionary movement was launched from its shores when William Carey set sail for India in 1793. Such Britons as Carey, John and Charles Wesley, Hudson Taylor, and William Booth helped set the course of missions, evangelism, and outreach in the modern Christian church.

In recent years, however, evangelistic zeal has all but died out in England. As Luis Palau told a mass rally last year in London’s Trafalgar Square, “I see plenty of religion but not much Christianity.”

The evangelist was right. Only 14 percent of England’s 50 million citizens attend church regularly. And at least one-third of the 7 million churchgoers would not claim to be born-again Christians.

To help reverse that trend, Palau and evangelist Billy Graham are mounting an ambitious evangelistic effort. Palau launched his Mission to London campaign last fall. Graham is preparing for evangelistic crusades in England beginning in May. Their combined efforts are designed to cover the country with the gospel message.

“England is no longer a Christian nation, but a pagan one,” Palau has said. Many British churches are populated by nominal Christians, or “professional churchgoers” as they are called in England. They often hold key positions within the church, making evangelistic outreach difficult.

The first stage of Palau’s campaign made a significant impact on London last fall. More than 210,000 persons attended his eight-week crusade, with an estimated 8,000 making public commitments to Christ. He will return to London in June to begin a month of nightly meetings. His no-holds-barred approach has led the British news media to label him the “ordinary man’s evangelist.”

Graham’s visit in May and June will concentrate on five regions outside London. Each area will present its own set of circumstances, from high unemployment to urban racism. During the months leading up to Graham’s visit, a small army of his American staff is training British church leaders to prepare congregations for the anticipated influx of new converts.

Both Graham and Palau are using mass media to great advantage in England. A newspaper editor became a Christian as a result of Graham’s most recent television appearance there. And Palau, interviewed on a Christian talk show, gave an invitation to receive Christ—a first for British television.

The interview that has caused the greatest stir was broadcast on the BBC’S “Everyman” program. An interviewer asked Palau, “Are you saying, if a person does not repent of their sins, does not ask Christ into their life, that person will not receive eternal life?” The evangelist replied, “That is correct.”

The interviewer’s query sums up the spiritual question that Britons all over the country are beginning to ask. In a few months, Palau and Graham will be there to provide the answer.

NIGEL SHARPin England

North American Scene

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) is supporting Sun Myung Moon’s appeal of his tax-fraud conviction. The Internal Revenue Service charged that the Unification Church leader failed to report income from stocks and a bank account held in his name. Moon maintains he was holding the assets in trust for church purposes. The SCLC plans to file a friend-of-the-court brief when Moon’s case goes before the U.S. Supreme Court. “The government does not have the right to tell a church how its funds should be administered,” says SCLC president Joseph Lowery.

A newly organized group of conservative Lutherans is concerned about the theological direction of the new Lutheran church to be formed from the merger of three Lutheran denominations. The Fellowship of Evangelical Lutheran Laity and Pastors (FELLP) sent a statement of “affirmation of faith and expression of theological concerns” to some 38,000 fellow Lutherans. FELLP has urged the new church to adopt the terms “inerrant and infallible” when describing the Bible. In addition, FELLP opposes theologies that imply that people can be saved without personal faith in Christ and repentance from sin.

The leader of the House of Judah sect has been found not guilty of child cruelty in the death of a 12-year-old boy at the sect’s camp in Michigan last summer. William Lewis, the sect’s founder, was acquitted because the prosecution could not prove he was responsible for protecting the boy. Police have charged that the boy’s mother and other sect members beat him for refusing to do his chores, a punishment prescribed by the sect. The boy’s mother still faces a manslaughter charge.

A federal judge has dismissed a suit brought against the Year of the Bible. The suit was filed by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) on behalf of 16 plaintiffs, including Jews, Christians, Buddhists, and atheists. The ACLU charged that a presidential proclamation and a congressional resolution recognized Christianity as the official religion of the United States. Chief U.S. District Judge Manuel Real said the measures did not have the force of law, and therefore did not mandate religious conduct.

Violent lyrics in rock music have increased 115 percent since 1963, according to the National Coalition on Television Violence (NCTV). The organization also reports substantial violence in music videos shown on the MTV cable-television channel. The NCTV says sadistic violence appears more frequently on MTV than on any other television channel.

A computer analysis of photos of the Shroud of Turin indicates that the burial cloth came from Palestine at the time of Christ’s death. Francis Filas, professor of theology at Loyola University in Chicago, says a “digital image analysis” detected letters that appear on coins that were placed on the eyes of the dead during the time of Christ.