It’s pitching its new movie to the Christian community.

“How many of you came to see a good film?” Roger Elwood of Disney Productions asked a largely Christian audience of several hundred at a private screening last month in Burbank, California.

Also on the bill were evangelist Rex Humbard, gospel singer Doug Oldham, CHRISTIANITY TODAY editor emeritus Harold Lindsell, cult specialist Walter Martin, Ben Roth of the Full Gospel Business Men’s Fellowship, and Cameron Wilson of World Literature Crusade. The program for the event was in church bulletin format. It featured biblical quotations and referred to the audience as a “congregation.” Ushers issued a two-page document explaining the theme of the movie (“1 John 2:16 is the theme of this film”) and offering interpretation of some of its “allegorical references”. The film in question was Disney’s Something Wicked This Way Comes, released nationally in late April. It is based on novelist Ray Bradbury’s taut, supernatural thriller of the same name, written in 1961.

If all of this seemed to be an unusual way to introduce a Hollywood film, even a Disney film, it was indeed. It is evident that Disney hopes it has the next Chariots of Fire. That film, distributed by Warner Brothers, was shown to Christian leaders around the country to generate interest before its national release. It was a box office success and was named best picture of the year for 1981. Disney is also leaning heavily on the evangelical community. The movie has been previewed in the Wheaton, Illinois, area, at First Baptist Church in Dallas, and at Philadelphia College of the Bible. Elwood, the Disney publicist, has been turning the previews into religious meetings, as evidenced by the program in Burbank. The film, however, does not seem to some to have as clear a Christian message as did Chariots of Fire. It does have a couple of gory scenes, and a genuinely frightening one in which a swarm of spiders invade a boy’s bedroom (a full review of the movie is on page 71).

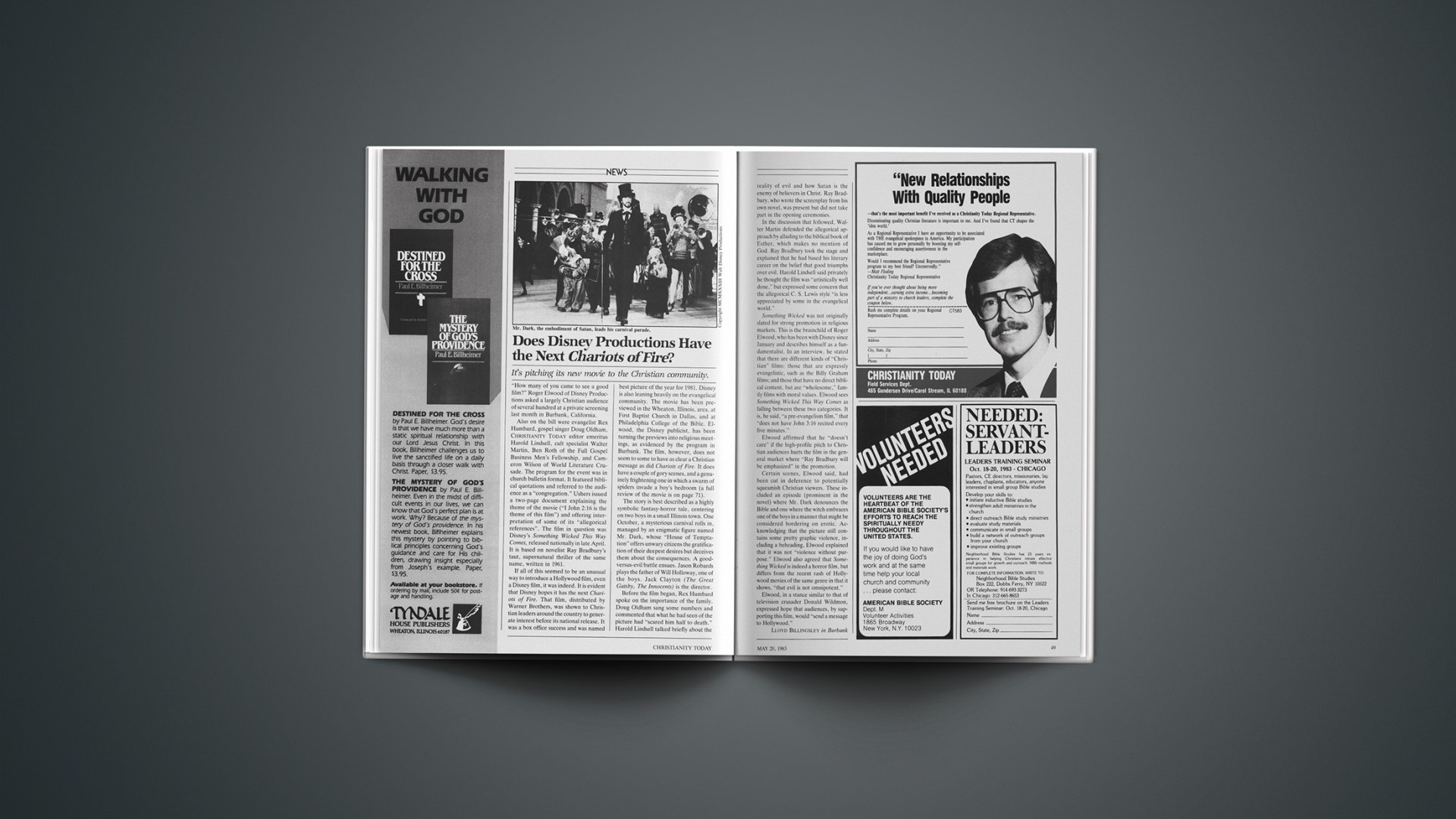

The story is best described as a highly symbolic fantasy-horror tale, centering on two boys in a small Illinois town. One October, a mysterious carnival rolls in, managed by an enigmatic figure named Mr. Dark, whose “House of Temptation” offers unwary citizens the gratification of their deepest desires but deceives them about the consequences. A good-versus-evil battle ensues. Jason Robards plays the father of Will Holloway, one of the boys. Jack Clayton (The Great Gatsby, The Innocents) is the director.

Before the film began, Rex Humbard spoke on the importance of the family. Doug Oldham sang some numbers and commented that what he had seen of the picture had “scared him half to death.” Harold Lindsell talked briefly about the reality of evil and how Satan is the enemy of believers in Christ. Ray Bradbury, who wrote the screenplay from his own novel, was present but did not take part in the opening ceremonies.

In the discussion that followed, Walter Martin defended the allegorical approach by alluding to the biblical book of Esther, which makes no mention of God. Ray Bradbury took the stage and explained that he had based his literary career on the belief that good triumphs over evil. Harold Lindsell said privately he thought the film was “artistically well done,” but expressed some concern that the allegorical C. S. Lewis style “is less appreciated by some in the evangelical world.”

Something Wicked was not originally slated for strong promotion in religious markets. This is the brainchild of Roger Elwood, who has been with Disney since January and describes himself as a fundamentalist. In an interview, he stated that there are different kinds of “Christian” films: those that are expressly evangelistic, such as the Billy Graham films; and those that have no direct biblical content, but are “wholesome,” family films with moral values. Elwood sees Something Wicked This Way Comes as falling between these two categories. It is, he said, “a pre-evangelism film,” that “does not have John 3:16 recited every five minutes.”

Elwood affirmed that he “doesn’t care” if the high-profile pitch to Christian audiences hurts the film in the general market where “Ray Bradbury will be emphasized” in the promotion.

Certain scenes, Elwood said, had been cut in deference to potentially squeamish Christian viewers. These included an episode (prominent in the novel) where Mr. Dark denounces the Bible and one where the witch embraces one of the boys in a manner that might be considered bordering on erotic. Acknowledging that the picture still contains some pretty graphic violence, including a beheading, Elwood explained that it was not “violence without purpose.” Elwood also agreed that Something Wicked is indeed a horror film, but differs from the recent rash of Hollywood movies of the same genre in that it shows, “that evil is not omnipotent.”

Elwood, in a stance similar to that of television crusader Donald Wildmon, expressed hope that audiences, by supporting this film, would “send a message to Hollywood.”

LLOYD BILLINGSLEYin Burbank

The Ncc Takes It On The Chin One More Time

First Reader’s Digest and then “60 Minutes” ignited controversy with reports that the National Council of Churches (NCC) supports left-wing political causes abroad. Now, the NCC is faced with fresh documentation that has sparks flying even closer to home.

The new investigation, published in two April issues of the weekly United Methodist Reporter (UMR) and its sister newspaper, the National Christian Reporter, examines the earlier criticisms with an evenhanded thoroughness that has won praise from both the council and its critics.

UMR editors sifted through NCC press releases, literature, and resolutions from the past five years and concluded that “the ‘leftist tilt’ of which the NCC has so often been accused” is “undeniably real.”

Unlike the previous mass media reports, UMR shifts the emphasis away from tales of church offerings that might be financing Third World guerrilla movements. Instead, it concentrates on what it sees as the real problem: “inconsistent and one-sided statements and staff actions.” The paper found a four-to-one tilt in favor of the Left.

For instance, the NCC has recommended cutting off U.S. economic development assistance to Latin American countries led by right-wing dictators, while advocating assistance for equally repressive Communist regimes such as the government of Vietnam. The paper reported that the NCC has been falsely accused of misusing church offering money to “buy guns” or contribute directly to Marxist revolutions.

The series of ten news articles and two editorials is particularly significant, coming from a well-respected voice of moderation published independently of the United Methodist Church. Associate editor and administrator Dan Louis said 11,000 requests for reprints have flooded in, and all but a handful of letters from readers have been “affirmative and supportive.”

The newspaper also commands attention from the NCC because the Methodists are the largest member denomination, supplying 40 percent of the denominational money the council receives.

NCC officials have not denied specifics in the report, but have some misgivings about the method used. NCC news service director Harriet Ziegler objected to UMR’s systematic perusal of NCC’s printed materials, saying, “I don’t think you can weigh published positions on human rights like pounds of potatoes.”

Other NCC officials told UMR that many of their human-rights efforts are kept confidential, so a false picture emerges when only public documents are considered. Other rationales offered by the NCC for a perceived leftward tilt include a long-standing commitment to critique U.S. foreign policy, especially in countries where missionaries have been most active; and a belief that left-wing repressive systems would be unresponsive to criticism anyway and require “quiet diplomacy instead.”

The newspaper’s investigation identified NCC’s internal structure as its primary source of imbalance, pointing out that most of its actions arise out of committees operating autonomously. The committees are staffed by people from denominational agencies who have particular expertise in an area of concern, such as human rights. UMR reporters found few active lines of accountability between these committees and the governing board.

They characterized the council as “a loose confederation of almost-independent organizations” and said, “This produces the worst of two worlds: the image of a powerful, centralized organization which is credited or blamed for all that is done under the NCC banner, and the reality of some 50 separate subunits each doing largely as it sees fit.”

NCC spokesmen say the lines of accountability go instead to NCC’s 32 member denominations, and they insist that NCC positions reflect priorities set by those churches. Among the most controversial aspects of the council is its linkage with independent advocacy groups.

One of these, the Interreligious Task Force on El Salvador, actively supported Marxists in that country, and did so from a rent-free NCC office, using NCC stationery. However, NCC claims to be officially nonpartisan toward foreign governments.

Claire Randall, NCC’s general secretary, explained that linkages forged in the past came at the mandate of a previous governing board, which restructured the NCC in 1972. Randall said, “We tried to be responsive, believing that was God’s call to us,” to help Christians living under repressive right-wing governments supported by the United States. But, she concedes, “maybe we overresponded. We have pulled back. It is much less a major part of our identity and work” than in the 1970s.

Randall said structural concerns about consistency and accountability at NCC are nothing new. To address these areas, the NCC in 1978 and 1979 sent “listening teams” around the country and formed a Presidential Panel on Future Missions and Resources in early 1982.

Randall views the UMR reports as a valuable addition to discussions that began shortly after she became the NCC’s chief executive in 1974. Since the investigation is not seen as an attack on the council, no formal reply is expected. “We keep evaluating ourselves and renewing ourselves” regardless of whether the council is attracting popular press attention, Randall said. “We’re not quite as helpless as we are painted.”

One of the NCC’s most vocal critics is the Institute for Religion and Democracy (IRD), a two-year-old Washington group composed mainly of conservative United Methodists and chaired by Edmund Robb, a Methodist evangelist. IRD’s board also includes Catholic author Michael Novak, evangelical theologian Carl F. H. Henry, and Lutheran theologian Richard John Neuhaus.

The organization’s director, Penn Kemble, hailed the UMR report as evidence that his group’s viewpoint is “gaining a hearing in the mainstream of church life.” Airing the issue publicly offers an unprecedented chance for revitalization in the church, Kemble said, as well as an opportunity for the NCC to be responsive to its constituents. “They would get a tremendous response from their congregations if they would address the problem honestly,” he said.

Battle-weary from its bouts with IRD, Reader’s Digest, and “60 Minutes,” the NCC welcomes the UMR scrutiny, despite its criticisms, as an authentic grassroots signal of directions it needs to consider taking. Randall said NCC will examine the newspaper’s recommendations—along with any others that come to light—and “give them all serious consideration.”

BETH SPRING

Lawsuits Against Bill Gothard’S Organization Are Dismissed

Two lawsuits filed last year against Bill Gothard’s Institute in Basic Youth Conflicts have been dismissed by federal courts in Chicago, A separate judge ruled on each.

The suits were brought by a group of former institute employees. One of the suits dealt with the allegedly unfair manner in which employees were treated. The other challenged the way in which money was spent. The lawyer for the plaintiffs said the matter is ended, and no appeals will be made.

Meanwhile, the institute reports substantial increases in attendance and donations. Some 40,000 pastors are expected to attend 21 one-day pastors’ seminars Gothard is conducting this year. About 30,000 came last year. Attendance at the first 11 seminars this year has been 20,000.

Last year, attendance at Gothard’s regular, week-long seminars for lay people totaled 330,000, and the institute expects that figure to rise by about one-third this year.

And Now, Live From Asbury Seminary …

Asbury Theological Seminary in Wilmore, Kentucky, inaugurated its fourth president, David McKenna, on April 16, in a ceremony dressed in all the pomp that befits such occasions. The day also featured a high-tech attraction the seminary hopes will change the course of continuing seminary education.

The inauguration ceremony was carried live via satellite to 31 sites across the country, where it was viewed by clergy and laymen in the middle of a one-day seminar. To receive a unit of continuing education credit, students were required to view morning and afternoon lectures, also beamed live by satellite from Asbury and read sections of two text books. They also had to write a synopsis of the course, which was titled “Empowering Clergy and Laity for the Ministry.”

The seminary is eagerly awaiting reports from the 31 sites indicating how well the event was received. First reports are that the participants were positive.

Corrie Ten Boom Dies At Age 91

The earthly pilgrimage of one of God’s most courageous children ended on April 15 with the death of Cornelia Arnolda Johanna ten Boom, known to countless thousands as “Corrie.” She died at her Placentia, California, home on her ninety-first birthday.

She is best known as the author of The Hiding Place, which told of her persecution at the hands of Nazis. The book sold more than a million copies, and the film of the same title has been seen by an estimated 15 million people. Corrie toured more than 60 countries with her message that “there is no pit so deep that Jesus is not deeper still.” She grew up in Haarlem, Holland, in a family deeply rooted in the Christian faith. She became a Christian at age five; in her youth and middle age she led church services for retarded children and was active in youth work at her church.

In 1918, Corrie became the first licensed woman watchmaker in Holland. The ten Boom family had owned the watch shop in Haarlem for more than 100 years, and Corrie thought she would carry on the tradition.

But during her fiftieth year, her life was suddenly interrupted as a result of the occupation of Holland by Nazis during World War II. The ten Boom family became a part of the underground movement to shield Jews in Holland from Nazi persecution. But they were discovered, and Corrie, a sister, her brother, and their father were imprisoned at a German concentration camp in Ravensbruck. Ten days later, Corrie’s 84-year-old father died. The bond between Corrie and her sister Betsie solidified. They shared a dream to tell the world of the joy and pain of their suffering for Christ.

But Betsie became one of the 96,000 women who perished at Ravensbruck, leaving the dream in the faithful hands of her sister. Because of a clerical error, Corrie was released from Ravensbruck just before thousands went to the gas chambers. She spent the rest of her life guarding the dream and guiding it to fruition.

Soon after World War II ended, she helped to turn what had been a concentration camp in Darmstadt, Germany, into a home for refugees and war victims.

Altogether, Corrie wrote 18 books with total worldwide sales of more than 6 million. But in 1977, it was evident she had a weak heart. She underwent surgery for a pacemaker, and suffered a stroke in 1978, which limited her ability to speak and write. In spite of this, she completed her last book, This Day Is the Lord’s.

The work she began will continue for a long time. A home she founded in the late 1940s for war victims operates today as a rehabilitation center for the physically and mentally handicapped. Already, the board of her ministry, Christians, Incorporated, has started a fund to continue the support Corrie had provided for eight overseas missionaries.

Part of the dream she shared with her sister was to tell the world “that when the worst happens in the life of a child of God, the best remains.” For Corrie ten Boom, the best has finally come. She has arrived at her final and most joyful hiding place.

Antiabortionists In Florida Can Keep Picketing

Christian antiabortion protesters in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, were awarded a favorable judgment after an abortion clinic lost its suit to keep protestors from picketing the clinic and witnessing to clients.

Broward County Circuit Judge Robert C. Abel, Jr., guaranteed picketers from the antiabortion group Omega the right to picket the A-Aastra Birth Control Information Center in Fort Lauder-dale, to carry controversial signs against abortion, and to counsel with women entering the clinic.

The trial was Florida’s first test case involving an abortion clinic and protesters. Picketing started at A-Aastra 10 months ago, after which the clinic sued Omega. The clinic owners claimed the demonstrations were affecting business by endangering patients’ health and causing tension and anxiety in the doctors performing the abortions.

The trial, in late March, drew packed courtrooms and TV cameras. Among the witnesses called by Omega’s attorney Tom Bush was a pastor who testified that Christians, by nature of their beliefs, were required to speak out against abortion.

Financial Trouble Besets Popular California Pastor

Gifted preachers whose messages and abilities attract thousands of people and great amounts of money sometimes get themselves into difficulty when they try to manage and spend large sums.

Such is the case with Ralph Wilkerson, pastor of the 10,000-member Melodyland Christian Center in Anaheim, California. In 1980, to avoid possible bankruptcy, the church property was sold for $4.3 million to a Canadian businessman and then leased back to the congregation. The results of an audit done in connection with that transaction have come to light in the Los Angeles Times, and the disclosures raise questions for a minister of the gospel. The article said that the Anaheim police department is investigating the church for possible fraud. While acknowledging that money was spent unwisely, allegations of fraudulent use of money are firmly denied by knowledgeable church members. Wilkerson himself is saying nothing in public in his own behalf, and neither are church officers.

Among the disclosures from the audit, as reported in the Los Angeles Times, are these:

• Between 1975 and 1978, Wilkerson received $237,384 in nonpayroll payments from the church, including $55,000 from the church building fund. This was in addition to salary and fringe benefits of $110,000 annually.

• Wilkerson and his family made 29 trips to foreign countries during the same period at church expense.

• The church paid American Express card charges of more than $62,000 for jewelry, shoes, clothing, and the like, for Wilkerson, family members, and the church pilot.

• About $3 million was deposited and withdrawn from 120 church bank accounts, with no record of where the money went.

• A $1.5 million building trust fund was spent on church bills and private loans.

Attendance has remained strong at the church, and a number of well-known ministers have rallied behind Wilkerson during the last few troubled months. They include Robert Schuller, Kenneth Copeland, and Jim Bakker, all of whom have appeared at the church, and James Robison, who is scheduled to appear.

Just last month the church congregation repurchased its property, and church officers are instituting a new, tough management plan, which takes Wilkerson completely out of handling finances. His only role will be to preach and function as a pastor. The management plan, called “Save Our Church,” calls for all debts to be paid off in two years.

Catholics Begin An Evangelism Magazine

The renewal movement in some parts of the Catholic church has spawned great interest in the Bible and in conservative Protestant notions of one’s personal relationship with Christ. Now, a new magazine is being published that crosses another gap between Protestant and Catholic expressions of faith—that of personal witnessing.

The Catholic Evangelist, a bimonthly published in Boca Raton, Florida, is billed as the only national Catholic magazine published by laypersons without church subsidies.

The magazine is aimed not only at active Catholics but also at church dropouts, estimated at 15 million Americans. The Evangelist also contains articles for the 80 million people who profess no religious affiliation.

The publisher and business manager is William Glass, a printshop owner who became a believer in Jesus Christ at a 1979 meeting of Christian businessmen.

The editor is Susan Blum, a convert from Presbyterianism and a lay leader in the archdiocese of Miami. She holds a master’s degree in pastoral ministry from Biscayne College, a Miami-based school run by the Augustinian fathers.

An informal, “over the coffee cup” approach to the gospel is a prime goal, said Blum. “There are a lot of good Protestant magazines like this one, but none for Catholics,” she said. “For a lot of people, ‘Catholic evangelist’ is a contradiction in terms.

“Many Catholics have grown up in the church without making a public commitment to Jesus Christ,” she added. “So one of our main jobs is to lead them into a stronger relationship with God, to strengthen their faith.”

The magazine has the endorsement of Miami Archbishop Edward A. McCarthy, a national pioneer in the Catholic lay renewal movement. He became honorary board chairman for the publication and wrote a half-page article for the first issue.

Topics in the first issue would look familiar in a Protestant magazine: how to be “saved,” how to read the Bible, how to pray, and personal stories of faith. There is also a study guide outline of the magazine’s entire contents, as an aid to discussion groups.

The cover bears a striking mélange of faces, including those of popes, Mahatma Gandhi, and John and Robert Kennedy; from a distance, they all merge into the thorn-crowned head of Jesus.

The Evangelist issue ventures into potentially hostile territory with two other features. One is a fictional letter from a “fallen-away Catholic,” voicing her confusion and resentment over church practices.

The other touchy article is a forum column for inactive Catholics, tellingly titled, “I Was Raised Catholic But …”

Funding for the magazine began with $10,000 in seed money from 10 donors, with some free advertising in the newsletter of Father Alvin Illig, head of evangelization for the U.S. Catholic bishops. Glass donates office space, and he and Blum work as volunteers.

Stacks of the Evangelist are being placed in area Christian bookstores, and samples are being mailed to out-of-town stores. Plans are for the magazine to grow to 20,000 subscribers within three years.

JAMES D. DAVIS

The Siberian Christians Finally Leave Their Refuge In Moscow

The people at the Christian Legal Society office in Oak Park, Illinois, knew something was up on Friday, April 8, when they received a call from Washington asking if they could procure $27,000 for fees and exit visas for 29 members of the Russian Vashchenko and Chmykhalov families—and could they get the money to Washington in 48 hours? Six members of the two families were still living in the American embassy in Moscow after nearly five years there, protesting the Soviet refusal to allow them to emigrate. But now the stand-off was ending.

A variety of Christian individuals and organizations had been collecting money to finance the emigration, but all of it had not yet come in when the call came to Oak Park. Personal loans were hurriedly arranged, and Lynn Buzzard, executive director of the society, boarded a plane for Washington with the check.

The following Tuesday the six Soviet Pentecostalists left the embassy to return to their Siberian home in Chernogorsk, thus ending one of the more remarkable displays of protest against religious repression the Soviet Union has seen.

The stalemate began to unravel rather abruptly earlier in the week when the Soviet government allowed one of the protesters, 32-year-old Lidia Vashchenko, to leave the country. She had been with the other six in the embassy until a hunger strike forced her hospitalization a year ago. When she recovered, she returned to her home in Chernogorsk and formally applied for emigration.

The Soviet government’s position all along had been that the Pentecostalists should leave the embassy and apply for visas. When Lidia did that, and her application was honored, the other six were convinced to leave their refuge and do likewise. Until then, they had been determined to remain in the embassy until their emigration was assured. None of the six have guarantees that they will get out.

After the release of Lidia, an organization known as the “Siberian Seven Working Group” was organized, with a branch in Israel, where Lidia is now, and a branch in the United States. The group hopes to raise a total of $200,000 to finance the orderly exiting and relocation of all 29 members of the families (15 Vashchenkos and 14 Chmykhalovs) when and if they are released. It is likely that the Vashchenkos will settle in Israel. The destination of the Chmykhalovs is uncertain.

Buzzard, who has been to the Soviet Union twice in the last two years to try to advance the cause of the families, is personally confident they will all be permitted to leave eventually, and he said others working to free them are also confident.

Lidia boarded a plane in Moscow on April 6 for her trip to Vienna. Her brother John and sister Vera accompanied her to the airport, and she left with them her only Russian Bible. The first person to welcome her to the West was Danny Smith of the London-based campaign to free the seven. He had been asked by the U.S. embassy in Moscow to get aboard the first plane to Vienna. He did, and was joined by Michael Rowe of Keston College, England, who had been in constant contact with the families in the embassy. Jane Drake from SAVE (Society for the Vashchenko/Chmykhalov Emigration), based in Alabama, and Ray Barnett, director of Friends in the West, a Seattle group, were also quickly on the scene.

After several days of frenetic behind-the-scenes activity, the Israelis were persuaded on Friday, April 8, to open their embassy after hours to issue Lidia a visa to enter Israel. She flew to Tel Aviv and faced a large news media turnout. She said, “I am happy to be in Israel. This is a dream come true for me. It is also the fulfillment of my family’s 20-year prayer. I would once again like to thank all those people, organizations, and governments that have made my emigration possible. I am looking forward to being united with my family.

One of the first things she did in Israel was to write a letter to Prime Minister Menachem Begin to thank him for his help. She went on to Tiberias, where many of her helpers, mainly from the United States, began arriving to celebrate her victory.

One of Lidia’s constant companions in Israel is Pirkko Huuhtanen, who is with a Finnish organization working for the release of the seven. Huuhtanen said Lidia was greatly surprised to find that other Christian emigrants from Russia have locked themselves away in the West. Lidia does not plan to do that.

Upon hearing that the rest of the seven had left the embassy in Moscow, Lidia asked for prayers from all Christians that their emigration would come soon, and she asked that letters be sent to the Soviet government petitioning the release. A reporter asked her what she thought her family would want to do if they were allowed into Israel. She thought for a moment and said with a slight smile, “Eight of my brothers and sisters have been waiting to be baptized in the Jordan River.”

There was no shortage of speculation among Lidia’s supporters about why the Soviets chose this particular time to release her. Some of them thought the Soviets do not want to be criticized on the issue of religious freedom during the upcoming World Council of Churches assembly in Vancouver this summer.

Lidia was also asked if her five-year ordeal in the embassy had increased her faith in God. She replied: “We have a hymn in Russian which says, ‘the greater the sorrow, the closer is God.’ ”

TOM MINNERY with DAN WOODINGin Tel Aviv

Martin Marty Says Christianity Is Tilting Toward The Baptists

World Christianity is becoming increasingly “Baptistificated” according to one of America’s best known church historians. Martin Marty told an audience of Baylor University religion faculty and Southwestern Seminary theological faculty that the Baptist form of Christianity, which emphasizes persuasion and decision, is gaining popularity over the “Catholic” form of nurture, which says “Christian children spring from the loins of Christian parents.”

Marty, professor of the history of modern Christianity at the University of Chicago, delivered two addresses at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, Fort Worth, as part of the seminary’s seventy-fifth anniversary observance. He is associate editor of the Christian Century, editor of the newsletter, Context, and coeditor of Church History.

Marty said Baptist strength comes from leaning on God, which is why he was so bemused by the Southern Baptist Convention’s passage last summer of a resolution affirming a constitutional amendment supporting school prayer. “Southern Baptists’ school prayer resolution leads us away from the power of God to the power of government to dictate the circumstances in which we work.”

Baptist tradition is typed as the “church of the disinherited,” he said. It is a creation of “people people” and “folk folk” who had the “unimpaired imagination” and “vehement force of need” to show where the power in society was missing the sources of need. Real power comes through weakness, he said, because “God works on us when he sees our power gone. Even our strongest institutions are so frail.” “The power of being an outsider meant you had no resource to fall on except the divine resource,” Marty said. Early Baptists did not have the burden of keeping the culture going. Baptists no longer are outsiders in most of America’s southland. They have become the religion of the culture in the areas of their strength.

BAPTIST PRESS

North American Scene

The Justice Department has dropped its investigation into the fund-raising tactics of Jim Bakker’s PTL organization. It had inherited the case from the Federal Communications Commission last December. A spokesman for the department said, “There was not enough evidence to show a violation of the federal criminal statutes, or that it will be a prosecutable case.”

Most editors of both national and diocesan Catholic publications are at odds with official church teaching on issues such as priestly celibacy, the ordination of women, and artificial birth control. The poll was conducted by the Catholic Communications Network in conjunction with the National Catholic Register. Most respondents oppose military aid in Latin America, feel that the Pope does not adequately understand the needs of the American church, and declare the use of nuclear weapons to be inherently immoral.

Southern Baptists are beginning to regret choosing Pittsburgh as the site of their 1983 convention, scheduled for mid June. Many of the 15,000 people expected to attend may have trouble finding a place to stay. Since 1978, when the Baptists made tentative housing arrangements, two hotels have shut down. Also, the U.S. Open Golf Tournament, scheduled for the same week, is posing a problem for Baptists seeking housing close to the steel city.

The nuclear arms freeze movement has become one of Jerry Falwell’s concerns. A war against the “freezeniks” is the basis for his most recent fund-raising drive. Falwell believes that “if the United States gives in to the freezeniks,” “we will someday find ourselves under Communist rule.” Falwell’s Moral Majority is working to establish a political action committee, which hopes to raise between $2 million and $4 million in the next two years to support President Reagan and conservative Senators Jesse Helms and Roger Jepsen, among others.

The News World newspaper, founded six years ago by Sun Myung Moon, has put out its final issue. But the same staff continues publishing in the same offices under a new name—the New York Tribune. Besides the name, the design of the paper is different. It carries a commentary section that its editors hope will be an alternative to that of the New York Times. The Tribune has the same typeface and layout as the Washington Times, a Unification Church-owned daily in Washington, D.C., with a circulation of about 120,000. Many New Yorkers avoided buying the News World because it is perceived as a propaganda organ of Moon’s church. But editors deny that the name change was to blur that association.

World Scene

Extensive flooding damage in Ecuador this spring on the Pacific side of the Andes mountains has led to new evangelical cooperative effort. The Ecuadorian Evangelical Fellowship was joined by Alfalit, HCJB, MAP International, Mission Aviation Fellowship, and World Vision in forming an Evangelical Relief Committee to coordinate relief efforts with the government and to channel funds and supplies.

Does church growth stall when conflict destabilizes a country? Several congregations in El Salvador have gone from one to three Sunday morning services during the civil-strife era of the last three years. Salvadorian churches with a CAM International origin report that their growth in baptized members has exceeded 120 percent over the last decade.

The British Methodist Church has decided it is useless to appeal a 1980 ruling by the country’s Board of Charities commissioners prohibiting grants to the World Council of Churches Program to Combat Racism. The commission ruled that fighting racism and promoting racial equality are incompatible with the charter of the denomination’s overseas division, which identifies its aims as promoting Christianity and helping establish churches overseas.

The editor of an evangelical journal within the Church of England has been fired. The March action signals deeper turmoil among “low-church” Anglicans over “liberalism in theology” and “Romanizing tendencies.” The Church Society, one of four evangelical groupings within the diverse state church, dismissed Peter Williams from the editorship of the Churchman, a respected quarterly that has been published for more than a century. The society wants the Churchman to articulate a conservative position, while the publication’s board champions a forum approach to topics such as biblical inerrancy, and women in ministry.

Deaths

C. Stacey Woods, 72, vice-president of the International Fellowship of Evangelical Students, of which he was a founding member and the first general secretary; also, founding executive director of Inter-Varsity Christian Fellowship, U.S.A.; April 10, in Lausanne, Switzerland, following successive strokes.

John D. Needham, 65, national commander of the Salvation Army; April 13, in Montclair, New Jersey, after a brief illness.