Not The Signs Of The Times

Armageddon Now!, by Dwight Wilson (Baker, 1977, 258 pp., $4.95 pb), is reviewed by Timothy P. Weber, assistant professor of church history, Conservative Baptist Seminary, Denver, Colorado.

Dwight Wilson, professor of history at Bethany Bible College, has written an intriguing and often disturbing study of American premillennialism in the twentieth century. Unlike most books on prophetic themes, this one is about the history of a school of interpretation, rather than the results of an interpreter’s study.

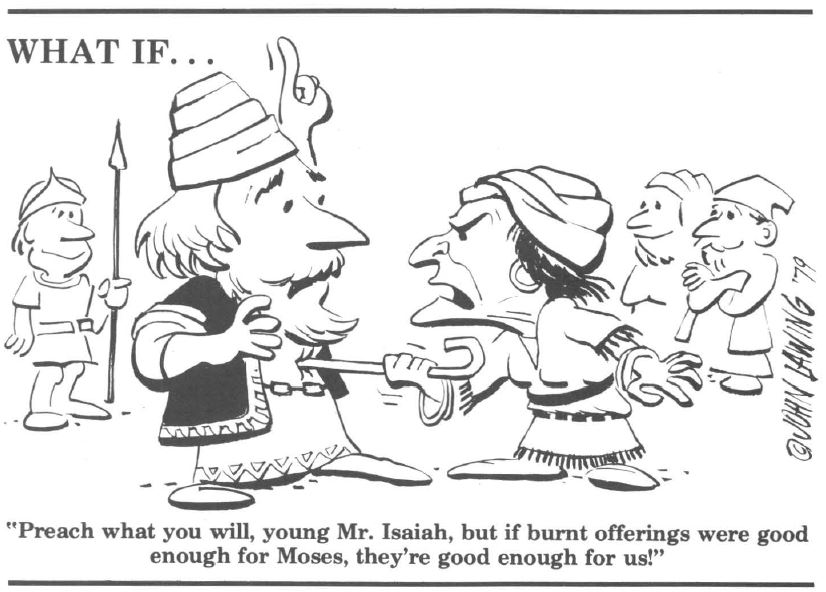

Basically using a chronological approach, Armageddon Now! traces premillennialist responses to Russia and Israel from 1917 to the present. Wilson argues that during those years premillennialism was characterized by a loose literalism that repeatedly failed in its attempt to match biblical prophecy and current events, a fatalistic determinism that often expressed itself in racism and denials of basic Christian justice, and an opportunism that employed sensationalism and prophetic blunders because such approaches were thought to be useful in saving souls.

Although premillennialists claimed to be able to identify the signs of the approaching end of the age, their history “is strewn with a mass of erroneous speculations which have undermined their credibility.” For example, at least some prominent premillennialists have interpreted nearly every major international crisis of this century as the harbinger of Armageddon, including the Russo-Japanese War, the two world wars, the war for Israeli independence, the Suez crisis, and the Arab-Israeli wars of 1967 and 1973. They saw the rise of the revived Roman empire of the last days in the League of Nations, the expansion of Mussolini’s Italy, the United Nations, the European Defense Community, NATO, and more recently the Common Market. They believed that the Russian-led northern confederacy was formed at the signing of the Brest-Livotsk Treaty, the Rapollo Treaty, the Nazi-Soviet Pact, and the rise of the Soviet Bloc after World War II. In due course, they identified the “kings of the east” as Turkey, the ten lost tribes of Israel, Japan, India, and China. Similarly, premillennialists pinpointed the start of the “latter rain” in 1897, 1917, and 1948; they marked the end of the “times of the Gentiles” in 1895, 1917, 1948, and 1967. Among possible candidates for Antichrist, premillennialists listed Mussolini, Hitler, and Henry Kissinger, to name a few. In light of this record, Wilson concludes that “such loose literalism … is not more precise than the figurative interpretations of which these literalists are so critical.”

Furthermore, the author claims that most premillennialists are guilty of a deterministic view of things, which is unethical and even antinomian. Because they believe that the world will get worse and worse before Jesus comes, premillennialists expend little energy trying to change it. For instance, since persecution of the Jews is a sign of the end, premillennialists have done little to stop it. Consequently, Wilson wants to hold premillennialists partly responsible for Russian, Nazi, and American anti-Semitism.

Wilson is even more critical of premillennialists’ carte blanche support of the state of Israel. Convinced that the founding of Israel was a fulfillment of biblical prophecy, they fail to apply to Israel the same standards of equity and justice that they demand of other states. For example, since the Bible promises the Jews the land from the Nile to the Euphrates, premillennialists tend to close their eyes and ears to any rightful claims of the native Arab population. To Wilson, such an attitude is nothing more than “the ends justify the means.” It forces premillennialists to applaud Israel for doing what they condemn in other nations. “Even if the right of Israel to exist as a nation be granted, the situation still demands that the decision be made on the basis of just and moral considerations rather than merely on the grounds that it fulfills prophecy.” In general, Wilson believes that premillennialists overlook the “usual definitions of aggression and violation of international law” for Israel.

Finally, Wilson contends that premillennialists excuse their frequent miscalculations and mistakes in prophetic interpretation because the cry of “Armageddon Now!” is such a useful evangelistic “tool of terror to scare people into making a decision for Christ.” In the battle for souls, “mights” and “maybes” are not nearly as effective as dogmatic and sensational “there’s-no-doubt-about-its.” Therefore, Wilson thinks premillennialist leaders are motivated more by a sense of opportunism than by any objective search for truth.

What should we say about this book? First of all, many premillennialists, especially those of the dispensationalist variety, are not going to like it. There is something unsettling about seeing the respected pillars of the premillennialist movement paraded in all their errant glory. But those who do not like the story Wilson tells will not be able to accuse him of lack of documentation for his point of view. In fact, at times the book seems to suffer from over-documentation. Too often the reader has the feeling that he is wading through capsule summaries of books and articles on prophetic themes or that he is covering familiar ground. The plot of the book frequently gets submerged in the details of who said what about which event in the light of biblical prophecy. Despite this heavy documentation, the book contains no index. For the scholar’s sake, I wish it did.

Wilson also has a tendency to overstate his case. To accentuate his thesis he occasionally resorts to a little benign sarcasm. In light of the enormous amounts of evidence he produces, some might think he showed remarkable reserve in some of the comments he made, but the material is powerful enough to speak for itself.

Furthermore, on a number of points Wilson seems unable to explain the obvious ambiguities within American premillennialism. For example, he does not adequately account for how premillenialists can be uncritically pro-Israel and anti-Semitic at the same time. Also he is hard pressed to explain why premillennialists who traditionally have refused to get involved in “political” causes have recently taken out ads in leading newspapers and formed ad-hoc organizations to undergird what appears to be a softening of U.S. support for Israel. Wilson claims that this becoming overtly political is simply a reflection of the growing concern of neo-evangelicalism with political issues. But this can hardly be the case since most premillennialists still would not call themselves neo-evangelicals, and though they might be willing to sign a petition on behalf of Israel, they would flatly refuse to sign one on behalf of open housing or world hunger relief.

Despite these shortcomings, Wilson has written an important book. For the most part, premillennialists have put all their time and energy into producing popular books on eschatology or more scholarly attempts to settle the many exegetical issues that still divide them. Very few, however, have written historical studies—except for polemical or apologetical purposes. I hope that as a result of Wilson’s work premillennialists will take their own history more seriously.

Especially now, during the current revival of interest in biblical prophecy, premillennialists can greatly benefit from the kind of poise and perspective the study of history brings. Once they discover the dismal record of attempting to match biblical prophecy with current events, contemporary premillennialists may hesitate to become too dogmatic with such identifications. If they know their past, premillennialists might be spared making the same kind of mistakes in the present. Wilson doubts it. He concludes that the patterns of opportunism and sensationalism are so deeply ingrained that the old patterns will continue, with premillennialism losing what credibility it has left. I for one hope he is wrong.

The Centrality Of Christ’S Resurrection

To Die and To Live: Christ’s Resurrection and Christian Vocation by Paul S. Minear (Seabury, 1977, 162 pp., $8.95), is reviewed by A. A. Trites, associate professor of biblical studies, Acadia Divinity School, Wolfville, Nova Scotia.

Minear introduces “a thought experiment” in the first part of his book, which he works out in the second. The experiment moves from the analysis of all communities to the analysis of religious communities. He isolates four problems facing the great religions of the world—the problems of revelatory agents, language, events, and the paradigmatic adequacy of the revelatory events. The chapter closes by noting that the Bible attempts a theistic answer to these concerns. The rest of the book is a serious effort to reveal the conceptual adequacy of the central events of Christianity—the death and resurrection of Christ. This task is attempted by an exposition of five key texts.

The first is Acts 3:15, which describes “the clarifying event” of the cross and resurrection. Here we have an illuminating study of three interlocking acts of murder, resurrection, and witness. Thus the death and resurrection of Jesus are twin events that are inseparable and interdependent and that have the power to unify many themes which otherwise would be entirely separate. Similar Christocentric patterns are observable in Hebrews 11 and 12, John 14, First Peter and Colossians 1. They offer varied but impressive testimony to the centrality of Christ’s death and resurrection. The chapter then outlines fourteen supporting propositions, and closes with some reflections on the “conflict of cosmologies,” which the author views as representing “the nub of modern misunderstanding of the gospel story.”

The remainder of the book unfolds the meaning of four texts. The first deals with Christ’s cross as a central theological event, which includes the crucifixion of the world (Galatians 6:14–15), the second with the cosmic vocation of the church (Ephesians 3:8–10), the third with the presence of Christ in his church (John 17:20–24), and the fourth with a prophetic vision of the end of the world (Mark 13:24–27).

To Die and To Live deeply probes Christian vocation as defined by the suffering, sacrificial character of Christ’s ministry. It unravels Paul’s “principalities and powers” and makes their exposition pertinent to contemporary Christian service. It studies the high priestly prayer in terms of “the bridge between the generations,” and it tackles the exegetically difficult Mark 13 passage with a concern to do justice to Mark’s original message to his readers faced with suffering and even possible martyrdom. The biblical correspondence between “first” and “last things” is carefully examined, and Galatians 6:14–15 is unfolded as a “triple crucifixion.”

This is a profound, seminal work, abounding in provocative comments, sensitive quotation of apposite poetry, and thoughtful insights into the mission of the Church. It demands to be read reflectively. The reader should ask, “Lord, what would you have me to do?”

Calls To Anti-Smut Activism

How to Stop the Porno Plague, by Neil Gallagher (Bethany Fellowship, 1977, 252 pp., $3.50 pb), Hustler for the Lord, by Larry Jones (Logos, 1978, 173 pp., $1.95 pb), and Telegarbage, by Gregg Lewis (Nelson, 1977, 164 pp., $2.95 pb), are reviewed by William T. Bray, communications consultant, Wheaton, Illinois.

The apparent powerlessness of evangelicalism to affect popular culture is the focus of these three controversial and disturbing books. Burning with a sense of moral outrage, they call evangelicals to spearhead the organization of broader community action against pornography and sexually explicit broadcasting. Two of the books do an admirable job as basic organization manuals. Telegarbage is the more motivational, and Porno Plague emphasizes community action and organization. Although more biographical and sensational, Hustler for the Lord carries the same theme. Whatever the real meaning of the proclaimed religious revival in the United States, it is apparently of no effect on the quality of mass media entertainment. Taken as a group, these books are somewhat frightening and often uncomfortably honest and forthright.

The underlying and usually unspoken accusation of all three books is the same: Evangelical indifference over the last 20 years lies at the root of the moral crisis in the communication arts. The authors advocate a brand of community activism that is not particularly associated with the sedate evangelicalism of this century. Not only are we very uncomfortable with the political process involved with attempting to set community standards, but our long neglect of the secular communication arts and entertainment fields has left us without alternatives to offer.

Thoughtful readers will quickly miss a strong biblical or theological basis for the community activism, corporate witness, and national standards of righteousness that are sought by these authors. The secularism of the apologetic stems from the object of their own personal crusades. They have been more concerned with the reaction of the news media, local government, the courts, and the police. It is obvious that all three men began their crusades without much community or church support. The courage that such antipornography campaigns require shows through from time to time as the prose gets tense and defensive. Some confrontations are described in a way that becomes almost embarrassingly personal. But you have to admire the kind of person who wages an all-out war against the local convenience store magazine rack.

Little in any of the books suggests real Christian alternatives. The response of these men is basically negative, but in light of the escalating emphasis on sex and violence in prime-time television it could be that a negative response would be better than no response at all.

The methods outlined in these books are constitutional and have worked time and again over the years. There is little new here, but much that is still untried by most evangelicals.

Telegarbage is by far the best written of the three. Television is defined as the cultural magnum force of our times. Lewis makes a lucid appeal for bringing it under control. “TV,” he insists, “has usurped many of the functions of religion. It provides explanations for the way things are; it interprets reality by offering its own world view. It establishes standards and values for attitudes and behavior.” The doctrines of the telecult he describes are sex, violence, and materialism. Because the influence of television is almost omnipresent in the U.S., today, Lewis thinks that even the strongest moral defenses can soften, tolerate, accept, and even adopt the messages presented on the screen. But the power of TV as a model for behavioral transfer is only part of the sinister influence. Lewis demonstrates that video is the principal force subliminally suggesting values and promoting consumer patterns that are opposed to Christian morality. As well as urging Christian protest and selective boycotts of programming, Lewis alone urges Christians to create alternatives for prime-time viewing. Evangelicals have got to begin “showing” their message instead of “telling” their message, if we are to have influence on the tube.

Telegarbage has names, sample letters, and action plans for Christians who want to take an active role in changing TV programming. An even greater wealth of such practical material is found in How to Stop the Porno Plague. Geared to the mass-marketing channels of distribution for books and magazines, the book tries to stay within constitutional and realistic approaches and strategies. The author believes that existing display and sales laws, properly monitored and enforced, could cripple the open distribution of obscenity in most American communities. How to Stop the Porno Plague is an encyclopedia of protest. The book reviews model obscenity ordinances and outlines the steps necessary to get them passed and enforced. Practically every aspect of a typical public information and agitation campaign is covered, including fundraising, educational activities, and media relations. Neil Gallagher is a tireless activist who has successfully plugged the mass-marketing pipeline for pornography in a number of communities. Out of his experience, he offers a number of thoughtful arguments and answers to almost any question or objection regarding why Christians protest obscenity. Gallagher’s mind for details is reflected in lists of definitions, sequential strategies, and samples of all kinds of printed materials used in antipornography protest campaigns.

Of the three titles, Hustler for the Lord is the most disappointing. Promoted as “the rebirth of Larry Flynt,” it is actually the disjointed tale of the running feud of an evangelist with Flynt and with local smut peddlers in Oklahoma. Sandwiched between contrived-sounding monologues representing confrontations that Larry Jones had while battling against Hustler magazine, are teasing references and anecdotes about Flynt, his family, and his staff. Jones never really delivers. Someone else will still have to write the real story of the Larry Flynt conversion. Most disappointed will be the reader who picks up the book to find out how Flynt is going to reconcile his publishing business with his new found faith. Hustler for the Lord is not all bad, but it reads like what it really is: a quick exploitation book hyped to sell in the wake of a sensational conversion. On the positive side, the genuine love that Larry Jones seems to have for Flynt does show through. So does the great courage that Jones has demonstrated in stepping out against the whole pornography industry. But this book can only be recommended for the hardy few who get deeply involved in the whole area.