June was the bloodiest month yet for missionaries caught in the six-year-old guerrilla war in Rhodesia. Twenty missionaries and dependents died violent deaths in the southern African nation last month. Unofficial reports put at sixteen the number who were killed in the previous eighteen months.

The deaths of the overseas white Christian workers were only a small part of the overall carnage. In addition to the military casualities on both sides, about 175 white civilians and large numbers of black civilians—estimates range from 2,000 to more than 3,500—have been killed. Many other blacks have been hideously maimed by terrorists.

More than half of the missionary deaths in June occurred at the Emmanuel mission school at Vumba, where eight adults—five of them women—and four children were murdered in a raid on the night of June 23. Another teacher died later of her injuries. The victims were axed, clubbed, and bayoneted.

Black colleagues on the faculty of the school, as well as the 250 black students, were rousted out of bed and told to leave, but none was hurt. According to the students, the raiders identified themselves as guerrillas of the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) force led by Robert Mugabe.

Mugabe, however, denied responsibility and blamed the Rhodesian government instead. He said that his “freedom fighters” were in touch with witnesses to the raid who recognized the murderers as members of the Rhodesian security forces. The Army unit known as the Sealous Scouts, he alleged, was the group responsible for the Vumba killings.

Similar charges were made last year in One World, a magazine published in Geneva by the World Council of Churches. The WCC periodical said that the secret commando unit at times dressed and equipped its forces like guerrillas in an attempt to discredit them in the eyes of the world. The unit’s attacks are concentrated on defenseless civilians in order to make it appear that the anti-government forces are completely heartless or uninterested in the kind of welfare work done by the victims, according to Army deserters quoted by the magazine. (ZANU has been a recipient of WCC anti-racism grants.)

The Vumba casualties were British Pentecostals affiliated with the Elim Mission of Cheltenham, England. Ronald Chapman, the mission’s director in Umtali, Rhodesia, declared after the raid that the killers were ZANU forces who had infiltrated from across the border in Mozambique, less than five miles from the school. At the mass funeral in Umtali, however, he said only, “We pray that God will be merciful to those who have perpetrated such an action of shame that they might know grief and repentance and God’s mercy.”

Aware of the possibility of such a raid, Elim officials had been making arrangements to house their personnel in Umtali, a fortified town ten miles from Vumba. The raid came only a couple of days before the victims were to be moved to Umtali.

Their funeral—at Umtali—was publicized around the world. A detailed account by reporter Michael T. Kaufman in The New York Times carried the headline: “Missionaries in Rhodesia Bury Dead Without Rancor.” Kaufman reported that Chapman and other “religious” speakers from various Christian groups “stressed the work of the dead missionaries in what was described as their imitation of Christ and offered praise and thanksgiving for their welcome into the kingdom of heaven.” He said that there was no hint of anger except in the remarks of Umtali mayor Douglas Reed. The mayor was quoted as telling the funeral throng of 600: “I am sure that most Rhodesians will join me in the fervent hope that the perpetrators of this ghastly deed will be speedily brought to justice.”

Clayfooted Idols

When Scotland’s soccer team left Glasgow to compete in the final stages of the recent World Cup series in Argentina, 30,000 fans gave them a rousing sendoff. Alas, they were quickly eliminated, after lamentable performances against outsiders Peru and Iran. The humiliation could be a judgment from God to punish the country for its “idolatry,” declared separatist clergyman Jack Glass. Said he: “I believe that God had to do something to show us that our football idols had clay feet and that the real victory is his.”

Such is the dismay among Scots that one of them resident in England took space in a newspaper renouncing the land of his birth and advertising for an elocutionist to help him get rid of his Scottish accent.

J. D. DOUGLAS

The Elim school was on property known as the Eagle school, which had enrolled only white children. It was vacated by the whites because of the frequent guerrilla incursions. The British missionaries had moved in after their own location farther north on the border of Mozambique had become even more exposed to hostilities.

Although not all Africans and missionaries agreed with the government view that ZANU headquarters had ordered the killings, there was wide consensus that guerrilla forces have a strategy of closing as many schools and other institutions as possible. Newsweek quoted the Anglican bishop of Mashonaland, Paul Burrough, as saying, “There is a concentrated effort on the part of the guerrillas to break down all community structures across the country, and the church is one of those structures.” The Washington Post quoted an unidentified Catholic priest as saying, “The guerrillas are telling the people, ‘Don’t go to church.’ ”

Some political analysts see the recent attacks as an attempt to so terrify the population that voters will not turn out for the upcoming national elections. The interim government formed by the “internal settlement” leaders have promised a plebiscite, but the “external” faction led by Mugabe and others does not want such a vote. One Rhodesian source told the Post correspondent, “If they can stop the children from going to school, then they can stop their parents from voting.”

School after school has been closing in the midst of the southern hemisphere’s academic year. Among the announced closings last month was Solusi College, the first Seventh-day Adventist missionary venture in Africa. Located near the Botswana border, it had been in operation since 1894 on land granted by Cecil Rhodes, founder of the country. Today Adventists in Rhodesia have 40,000 baptized adult members in 225 congregations. In addition to the 125-student senior college, a secondary school with 241 pupils and an elementary school with 232 were also closed. Political unrest was cited by Adventist officials as the reason for the action.

Throughout the nation, missionaries have had a prominent role in education. Statistics for 1977 indicate that mission-operated schools enrolled 60 per cent of the high school population and 10 per cent of the primary school population. Some missionary schools had been forced to close before 1977, but Christian teachers from abroad were still instructing more than 117,000 Rhodesians last year.

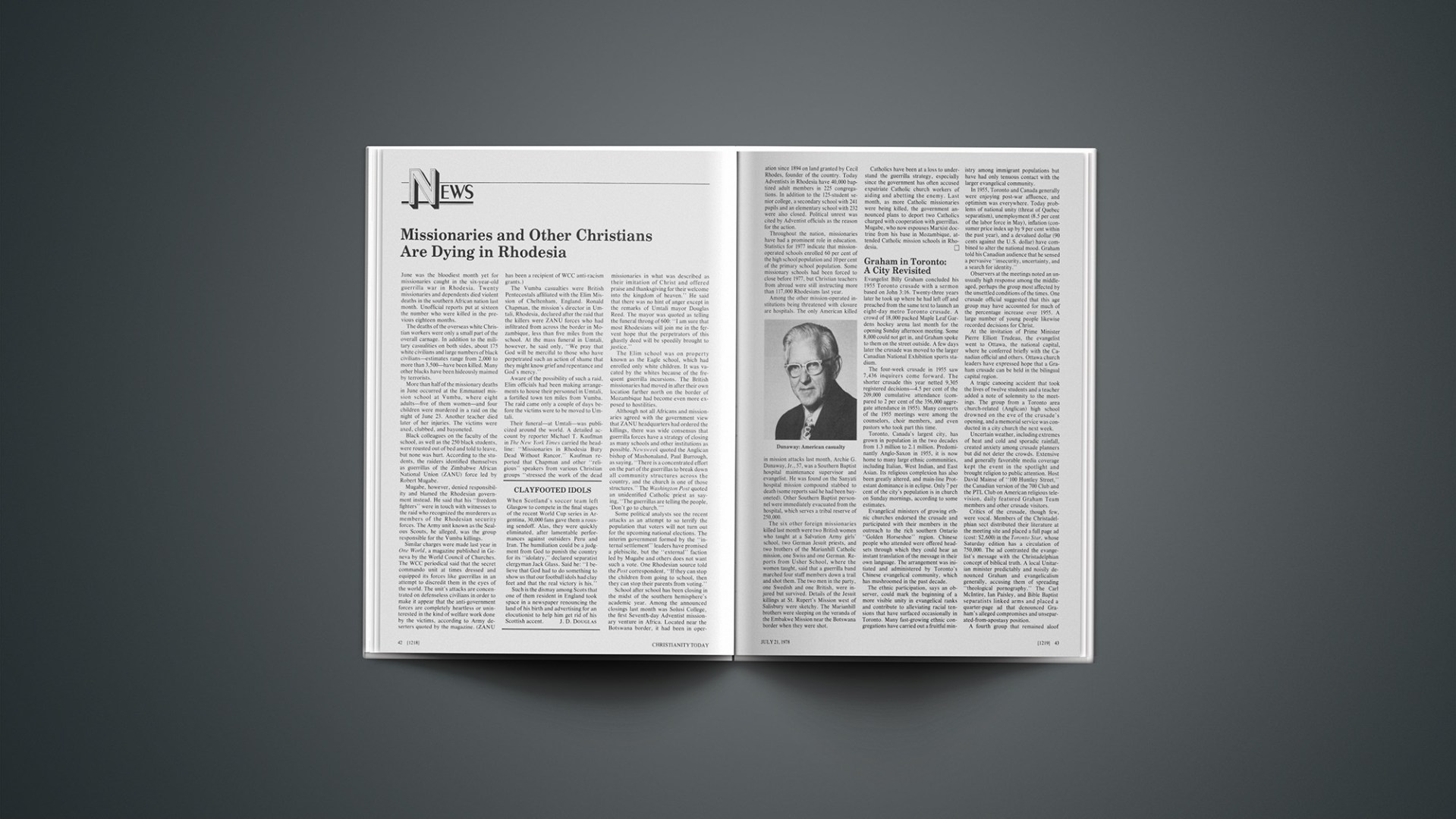

Among the other mission-operated institutions being threatened with closure are hospitals. The only American killed in mission attacks last month, Archie G. Dunaway, Jr., 57, was a Southern Baptist hospital maintenance supervisor and evangelist. He was found on the Sanyati hospital mission compound stabbed to death (some reports said he had been bayoneted). Other Southern Baptist personnel were immediately evacuated from the hospital, which serves a tribal reserve of 250,000.

The six other foreign missionaries killed last month were two British women who taught at a Salvation Army girls’ school, two German Jesuit priests, and two brothers of the Marianhill Catholic mission, one Swiss and one German. Reports from Usher School, where the women taught, said that a guerrilla band marched four staff members down a trail and shot them. The two men in the party, one Swedish and one British, were injured but survived. Details of the Jesuit killings at St. Rupert’s Mission west of Salisbury were sketchy. The Marianhill brothers were sleeping on the veranda of the Embakwe Mission near the Botswana border when they were shot.

Catholics have been at a loss to understand the guerrilla strategy, especially since the government has often accused expatriate Catholic church workers of aiding and abetting the enemy. Last month, as more Catholic missionaries were being killed, the government announced plans to deport two Catholics charged with cooperation with guerrillas. Mugabe, who now espouses Marxist doctrine from his base in Mozambique, attended Catholic mission schools in Rhodesia.

Graham in Toronto: A City Revisited

Evangelist Billy Graham concluded his 1955 Toronto crusade with a sermon based on John 3:16. Twenty-three years later he took up where he had left off and preached from the same text to launch an eight-day metro Toronto crusade. A crowd of 18,000 packed Maple Leaf Gardens hockey arena last month for the opening Sunday afternoon meeting. Some 8,000 could not get in, and Graham spoke to them on the street outside. A few days later the crusade was moved to the larger Canadian National Exhibition sports stadium.

The four-week crusade in 1955 saw 7,436 inquirers come forward. The shorter crusade this year netted 9,305 registered decisions—4.5 per cent of the 209,000 cumulative attendance (compared to 2 per cent of the 356,000 aggregate attendance in 1955). Many converts of the 1955 meetings were among the counselors, choir members, and even pastors who took part this time.

Toronto, Canada’s largest city, has grown in population in the two decades from 1.3 million to 2.1 million. Predominantly Anglo-Saxon in 1955, it is now home to many large ethnic communities, including Italian, West Indian, and East Asian. Its religious complexion has also been greatly altered, and main-line Protestant dominance is in eclipse. Only 7 per cent of the city’s population is in church on Sunday mornings, according to some estimates.

Evangelical ministers of growing ethnic churches endorsed the crusade and participated with their members in the outreach to the rich southern Ontario “Golden Horseshoe” region. Chinese people who attended were offered headsets through which they could hear an instant translation of the message in their own language. The arrangement was initiated and administered by Toronto’s Chinese evangelical community, which has mushroomed in the past decade.

The ethnic participation, says an observer, could mark the beginning of a more visible unity in evangelical ranks and contribute to alleviating racial tensions that have surfaced occasionally in Toronto. Many fast-growing ethnic congregations have carried out a fruitful ministry among immigrant populations but have had only tenuous contact with the larger evangelical community.

In 1955, Toronto and Canada generally were enjoying post-war affluence, and optimism was everywhere. Today problems of national unity (threat of Quebec separatism), unemployment (8.5 per cent of the labor force in May), inflation (consumer price index up by 9 per cent within the past year), and a devalued dollar (90 cents against the U.S. dollar) have combined to alter the national mood. Graham told his Canadian audience that he sensed a pervasive “insecurity, uncertainty, and a search for identity.”

Observers at the meetings noted an unusually high response among the middle-aged, perhaps the group most affected by the unsettled conditions of the times. One crusade official suggested that this age group may have accounted for much of the percentage increase over 1955. A large number of young people likewise recorded decisions for Christ.

At the invitation of Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau, the evangelist went to Ottawa, the national capital, where he conferred briefly with the Canadian official and others. Ottawa church leaders have expressed hope that a Graham crusade can be held in the bilingual capital region.

A tragic canoeing accident that took the lives of twelve students and a teacher added a note of solemnity to the meetings. The group from a Toronto area church-related (Anglican) high school drowned on the eve of the crusade’s opening, and a memorial service was conducted in a city church the next week.

Uncertain weather, including extremes of heat and cold and sporadic rainfall, created anxiety among crusade planners but did not deter the crowds. Extensive and generally favorable media coverage kept the event in the spotlight and brought religion to public attention. Host David Mainse of “100 Huntley Street,” the Canadian version of the 700 Club and the PTL Club on American religious television, daily featured Graham Team members and other crusade visitors.

Critics of the crusade, though few, were vocal. Members of the Christadelphian sect distributed their literature at the meeting site and placed a full page ad (cost: $2,600) in the Toronto Star, whose Saturday edition has a circulation of 750,000. The ad contrasted the evangelist’s message with the Christadelphian concept of biblical truth. A local Unitarian minister predictably and noisily denounced Graham and evangelicalism generally, accusing them of spreading “theological pornography.” The Carl McIntire, Ian Paisley, and Bible Baptist separatists linked arms and placed a quarter-page ad that denounced Graham’s alleged compromises and unseparated-from-apostasy position.

A fourth group that remained aloof from the crusade was a large segment of the United Church of Canada, the country’s largest Protestant denomination. A prominent United Church minister, J. Berkeley Reynolds, was a vice chairman of the crusade committee, and individual United Church ministers and members actively participated. However the well-known United Church Observer editor, A. C. Forrest, and other denominational leaders were openly critical of what they regarded as Graham’s failure to address social ills.

A school of evangelism that was conducted in conjunction with the crusade attracted about 900 ministers, seminarians, and other church leaders from five provinces, twenty-eight states (U.S.), and seventy-one denominations.

The Graham team includes a proportionately large number of Canadians—Leighton Ford, George Beverly Shea, John Wesley White, Ralph Bell, Tedd Smith, and Homer James. Another Canadian honored at the crusade was evangelical patriarch Oswald J. Smith, 88-year-old founder of Toronto’s Peoples Church, world missionary statesman, and author of numerous books and hundreds of hymns. Graham paid public tribute to the veteran minister. The 1,600-member Peoples Church, whose present pastor is Paul B. Smith, son of the founder, strongly supported the crusade.

The crowd of 45,000 at the closing service seemed deeply stirred as the 4,500-voice crusade choir made the lakefront stadium echo to the powerful strains of “How Great Thou Art.” That hymn, of Scandinavian origin but now familiar to English-speaking audiences everywhere, was introduced to North America at the 1955 Toronto crusade.

Crusade chairman Desmond Hunt, Anglican rector of the downtown Church of the Messiah, reported that the $643,000 budget had been over-subscribed and that the surplus would be designated to purchase of television time in Canada and to alleviation of suffering in the typhoon-stricken area of India, where the Graham organization has been sending aid.

Other Graham crusades this year are scheduled to be held in Kansas City, Oslo, Stockholm, and five cities in Poland (October 6 to 16).

LESLIE K. TARR

Graham: A Deficit

The Billy Graham Evangelistic Association (BGEA) and five affiliate organizations posted a combined deficit of $3.2 million last year, according to the first full financial report made public by Graham’s Minneapolis headquarters.

The statement shows that the six groups had a total income last year of $38.4 million and expenditures of $41.6 million, 89 per cent of it for evangelism and 11 per cent for administration and fund-raising. Income of the BGEA itself was $27.7 million, down $1 million from 1976, and expenditures were $30.4 million, up $2.7 million. Comparative figures covering the two years were not available for the affiliates: World Wide Pictures, World Wide Publications (also known as Grason), the Blue Ridge Broadcasting Corporation (which operates a religious radio station in Black Mountain, North Carolina), the Christian Broadcasting Association (which operates a radio station in Honolulu), and the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association of Canada. The totals do not include finances of evangelistic crusades; these are handled by local committees.

A separate report for the Dallas-based World Evangelism and Christian Education Fund (WECEF) shows a balance of $15.5 million at the end of 1977 after $7.7 million was released during the year for construction of the Graham Center at Wheaton College in suburban Chicago. The balance is earmarked for completion of the center and for other projects. Graham set up the fund in 1970 to aid projects in missions, evangelism, and Christian education. Some of the money comes from the BGEA.

Newspaper stories about the generally unknown WECEF account, along with certain disclosure requirements that surfaced in Minnesota, preceded issuance of the financial report, which cleared the air. Normally, parachurch agencies are required to file public financial statements with the Internal Revenue Service, but the BGEA is exempt because it is listed in government files as a church.

The Graham organization has nothing to hide, explained BGEA executive vice president George Wilson to reporters. It’s just that the “little” donor, whose average gift of $ 10 or so accounts for most BGEA income, might be discouraged from giving when he sees the millions of dollars listed on financial reports, he suggested.

It is unclear if the hubbub in the press over Graham finances contributed to the dip in income. Among other things, Wilson blames weather conditions that impeded mail service last winter. (Some observers point out that with the proliferation of television preachers—many vying for virtually the same pool of contributors to underwrite their multi-million-dollar budgets—a pinch was inevitable.)

Whatever, possible cutbacks are being considered in BGEA radio and television programming in order to deal with the declining dollars and escalating costs (especially in postage), Wilson told a Minneapolis reporter.

Record Offering

Ever the possibility thinker, television pastor Robert H. Schuller of the Garden Grove Community Church in the Los Angeles suburbs announced a Sunday offering goal of $1 million for June 18. The money, he said, was needed to continue construction of the $14 million mostly glass Crystal Cathedral next door. For more than two months he plugged the special offering. When the appointed Sunday finally arrived, Schuller led off the collections with his own contribution of $150,000—the profit from a sale of a condominium he bought nine years ago with a $9,000 down payment and $30,000 mortgage. Instead of offering plates, the ushers used hardhats and wheelbarrows. Into them was dropped $1,251,376 in cash and checks by the some 5,000 persons in the three morning services, Schuller later announced.

It may be a record for a church offering on a single day. Church spokesman Michael Nason said the previous largest known collection in one day was $886,881 on May 22, 1977, for a building project at the Broadway Church of Christ in Lubbock, Texas.

Canada: Issues of Unity

No Christians have the right collectively to assert that any specific constitutional arrangement—past, present, or future—possesses divine approval, the 104th General Assembly of the 169,000-member Presbyterian Church in Canada (PCC) was told when it met last month in Hamilton, Ontario. The 250 commissioners (delegates) were listening to a report of a special committee on national unity, chaired by clergyman William R. Russell of Montreal.

All constitutions are basically human inventions, said the committee. It added: “Nevertheless, in its divinely appointed mission as the conscience of the state, the church has the responsibility to speak out on behalf of unity in difference. This principle is implicit in the Christian understanding of human relationships.”

The threat of separatism posed by the province of Quebec led the 1977 PCC assembly to appoint a committee representative of all parts of Canada to study and report upon the church’s attitude toward this danger to Canadian unity. The comprehensive report, printed in both French and English, was largely a theological statement based on “The Declaration of Faith Concerning Church and Nation,” a document adopted by the PCC some twenty years ago.

The assembly approved the special committee’s statement which called for an atmosphere of openness and an attitude of reconciliation on the part of all Canadians as they face political developments, especially as they relate to Quebec and issues of national unity.

Proposals for closer relationships with the United Church of Canada brought forward after three years of conversations with a delegation from that body were sent to the PCC’s forty-four presbyteries for study and report to the 1979 General Assembly. A joint report on the conversations, which at no time dealt with organic union, called for closer cooperation at every level of church life, an annual national consultation concerned primarily with doctrine, mission and social action, and initiation of changes in present practice that would permit mutual reception of ministers by the two denominations.

Last year’s General Assembly turned down a request for financial help and support from the Presbyterian Church of Australia. That church was being split at the time by the union with Congregationalists and Methodists. About two-thirds of the Presbyterians entered the uniting church. This year’s assembly turned down the recommendation of the Committee on Inter-Church Relations that the two churches be given equal recognition. Instead it reaffirmed its fraternal relationship with the Presbyterian Church of Australia and recognized the Uniting Church of Australia simply as “a member of the World Alliance of Reformed Churches.”

In swift action without any hint of dissension the commissioners elected two college principals (presidents). William Klempa will go from Rosedale Presbyterian Church in Toronto to Montreal on August 1 as principal of Presbyterian College. J. Charles Hay, who has acted as principal of Knox College, Toronto, since the death a year ago of Allan L. Farris, was given permanent status.

However, the appointment of a professor of church history to fill a teaching vacancy left by Farris prompted debate. Many commissioners were apparently upset because the search committee proposed a U.S. candidate rather than one of the several Canadians nominated by presbyteries. By a vote of 98 to 94 the General Assembly appointed the committee’s choice, Calvin Augustine Pater of Westport, Massachusetts, a recent Harvard graduate.

The commissioners met against the backdrop of a somewhat forboding special issue of the denomination’s publication, The Presbyterian Record. It dealt with “The State of the Church.” One of the contributors wrote: “Were the present trend to continue, there is little doubt that our denomination soon would be reduced to a mere remnant.” Editor James Dickey pointed out that the membership of the denomination is declining at the rate of 3,206 people a year and that it has become the oldest religious body in Canada in terms of membership age. The church’s comptroller said that “real” giving in the church is also on the decline, and he projected sizeable deficits for 1978 and 1979.

The downward trends have prompted some of the denomination’s leaders to do a lot of hard soul-searching, the publication indicates. To reverse the trends, say the writers, there must be a “return to basics” and a rediscovery of a “distinctive Presbyterian witness.”

DECOURCY H. RAYNER

Sainthood And Taxes

It was only a matter of time before mail-order religion king Kirby J. Hensley of Modesto, California, got around to elevating mortals to sainthood. Five dollars will do it, he says, and the amount includes a certificate that attests to the canonized status. “A ticket to see Saint Peter,” he calls it.

Hensley, 66, founded the believe-whatever-you-wish Universal Life Church fifteen years ago by offering clergy credentials through the mail for two dollars. That was about 6.5 million “ordinations” and 30,000 “church charters” ago, he estimates. His enterprise also provides a doctor of divinity degree for $20. A doctor of philosophy in religion degree is conferred for a donation of $100.

Hensley, who employs about a dozen workers, claims he takes no salary from the church. He tells reporters that he was once a hobo and that he has never learned how to read and write. He apparently knows how to sign his name on checks, however. His organization’s average income exceeds $1 million annually, but in good years it has been much better than that, according to Hensley watchers. Hensley declines to comment about finances.

Benched

Remember municipal court judge Hugh Wesley Goodwin of Fresno, California? He’s the judge who attracted wide attention—much of it critical—for offering some criminal defendants the option of mandatory attendance at church services and Bible studies instead of jail sentences. He was defeated in an election last month and will leave the bench at the end of the year, when, he says, he will become “a missionary.” Some people, apparently ignoring testimonies of changed lives and attitudes, want him out sooner. A judiciary watchdog committee has filed formal misconduct charges against him for mixing religion with his rulings. The judge vows that he will fight the charges. It’s okay to separate the church from the state, he says, but it’s a “serious mistake” to try to separate God from government.

Goodwin, the son of a minister, a descendent of slaves, and the county’s first black judge, said his defeat in the recent election was “a message from God that I have accomplished my mission here and it’s time to move on.”

Government officials in New York don’t think the Hensley operation is a laughing matter. In 1976, 211 of the 236 adult residents of Hardenburgh. a rural New York town of low-income workers, obtained ordinations from Hensley in hopes of gaining relief from property taxes. Several non-profit organizations had bought large parcels of land in the area, removing them from the tax rolls and creating a heavier burden for local citizens (see October 22, 1976, issue, page 48). Tax assessors in Hardenburgh and in three neighboring clergy boom towns granted tax exemptions to the newly ordained. In doing so, the assessors violated explicit instructions from the state’s Board of Equalization and Assessment.

The case ended up in court, and last December a New York State Supreme Court justice ruled that the Hensley ministers were improperly removed from the tax rolls. The judge permitted them to remain off the rolls this year, though, because his ruling came so late. Under the ruling, assessment review boards in the towns are to decide if the mail-order clerics should be restored to the tax rolls. This will involve following “ample guidelines” established by the courts to determine whether the Universal Life Church is a religion under state law. Whether such reviews will be free from bias is open to question. The members of the Hardenburgh tax review board, for example, hold ordination credentials from Hensley.

Tax assessor Robert Kerwick says that 213 “ordained” taxpayers in Hardenburgh alone have received church charters and are holding religious services in their homes for family members and friends. The homes have all been removed from the property tax rolls, he told CHRISTIANITY TODAY, because they function primarily as live-in places of worship. Hearings have been held to determine whether they qualify, and the “ministers” have brought in records showing that services indeed were being held.

“A lot of people may be reading the Bible for the first time,” commented Kerwick. He noted that a lot of the services centered on studies in the book of Genesis. (Many of the town’s residents also attend services of the Episcopal and Reformed Church in America churches in town.)

It costs $6,800 to send a Hardenburgh youngster to school, said Kerwick. Who is picking up the tab, now that virtually everybody in town is exempt from taxes? Other New Yorkers, he replied.

The people in Hardenburgh have a point in what they are doing, said Kerwick. They want to force the state to do something about the problem of higher taxes that are the result, at least partially, of exemptions being granted to an ever increasing number of non-profit corporations, he indicated.