From the December 3, 1976, issue of Christianity Today:

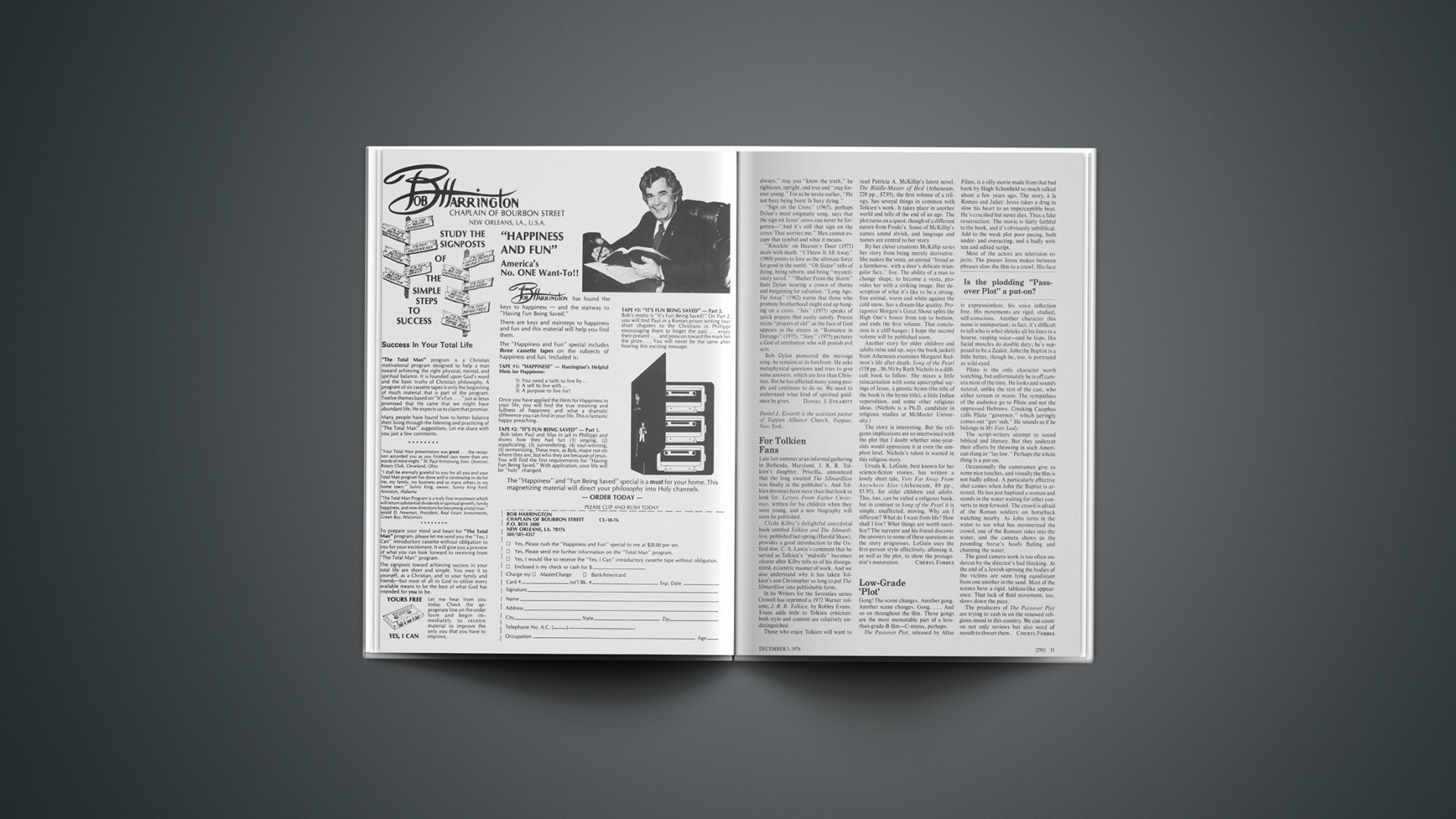

Sixteen years ago nineteen-year-old Robert Zimmerman moved from Minnesota to New York City. He left behind his past, his family, and his name. Ahead was his new life as Bob Dylan, influential singer-songwriter. Over the years countless artists have recorded Dylan's songs, and he has toured the world. Dylan is one of the three major trendsetters in popular music, the other two being Elvis Presley and the Beatles. The press has hailed him as a prophet, a leader, a teacher, a messiah, a poet, the voice of young America, and the conscience of his generation. Dylan says he's just a songwriter.

Throughout his career Dylan has reflected his religious upbringing. Raised in a strict Jewish home, he fills his songs with religious language, biblical references and characters, and theological questions. He views man in the light of the cosmic struggle between good and evil. Man must choose to follow God and truth or fall into death, decay, and ultimate judgment.

"Gates of Eden" (1965) says the world is evil but "there are no sins inside the Gates of Eden." Dylan sees the world as "sick … hungry … tired … torn/It looks like it's a-dyin' an' it's hardly been born" ("Song to Woody," 1962); as a "concrete world full of souls" ("The Man in Me," 1970); and as a "world of steel-eyed death and men who are fighting to be free" ("Shelter From the Storm," 1974). Technologically advanced America threatens human freedom, feels Dylan, who confesses that "the man in me will hide sometimes to keep from being seen/ But that's just because he doesn't want to turn into some machine." In "It's AIright, Ma (I'm Only Bleeding)" (1965), his sermon in song line by line decries the phoniness of society's games. "Human gods" make "everything from toy guns that spark/ To flesh colored Christs that glow in the dark." "Not much is really sacred," Dylan concludes.

Early in his career Dylan wrote many finger-pointing songs about man's inhumanity to man. He sang out against racial prejudice, hatred, and war. "Blowin' in the Wind," perhaps his most famous song, asks, "How many ears must one man have/Before he can hear people cry?"

Freedom and sin are major themes in a number of Dylan's songs. "With God on Our Side" (1963) is a satirical justification of war. In "Masters of War" (1963) he lashes out at the war profiteers who make money from young men's lives. He concludes that "Even Jesus would never/Forgive what you do." This cool, calculated evil will be punished, for "All the money you made/Will never buy back your soul." Dylan retells the story of Abraham and Isaac in "Highway 61 Revisited" (1965). Abraham questions God, who replies, "You can do what you want Abe, but/The next time you see me coming you'd better run." Abraham complies, knowing that peace with God comes only through obedience to God's directives. Ten years later Dylan reiterated that in "Oh Sister": "Is not our purpose the same on this earth/ To love and follow His direction?"

Hard Rain, his most recent album, contains a live concert version of "Lay, Lady, Lay," written in 1969. Dylan adds these lyrics: "You can have the truth/But you've got to choose it." Is man ultimately responsible for sin? Is man really free? Yes, man is free to choose to obey or disobey divine directives, but he is responsible and will be judged ("I'd Hate to Be You on That Dreadful Day" and "Whatcha Gonna Do?," 1962).

Dylan reads the Bible, and his favorite parts are the parables of Jesus. The album John Wesley Harding, recorded in 1968, two years after his nearly fatal motorcycle accident, contains a song patterned after those parables. "The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest" tells of Frankie Lee's thirst for wealth and his sensual lust, which ultimately bring his downfall and death. Frankie Lee denies that eternity exists. Dylan moralizes, "Don't go mistaking Paradise for that home across the road." So many people fail to think of anything besides their own quest for wealth; eternity means nothing to them. "Three Angels" (1970) play horns atop poles as people, oblivious, hurry by. "Does anyone hear the music they play?/ Does anyone even try?"

Dylan views man spiritually. In "Dirge" (1973) he confesses, "I felt that place within/ That hollow place/ Where martyrs weep/ And angels play with sin." In "Simple Twist of Fate" (1974) he writes of one who "Felt that emptiness inside/ To which he just could not relate." Man's spiritual cavity too often remains vacant.

Dylan has criticized the established religious institutions. "Got no religion. Tried a bunch of different religions. The churches are divided. Can't make up their minds and neither can I," he said early in his career. He hit at the attempts of churches and preachers to be relevant in "Stuck Inside of Mobile With the Memphis Blues Again" (1966):

Now the preacher looked so baffled

When 1 asked him why he dressed

With twenty pounds of headlines

Stapled to his chest

But he cursed me when I proved it to him.

Then 1 whispered. "Not even you can hide.

You see, you're just like me.

I hope you're satisfied."

Religious institutions are impotent: "The priest wore black on the seventh day/ And sat stone-faced while the building burned" ("Idiot Wind," 1974).

Dylan views God pantheistically. "I can see God in a daisy," he told an interviewer. "I can see God at night in the wind and rain. I see creation just about everywhere. The highest form of song is prayer. King David's, Solomon's, the wailing of a coyote, the rumble of the earth." In his modern-day psalm "Father of Night" (1970), Dylan praises God as the creator of night and day, heat and cold, loneliness and pain. He is the Father of all "who dwells in our hearts and our memories," the "Father of whom we most solemnly praise." Dylan's prayer for his generation and all succeeding people is outlined in "Forever Young" (1973): "May God bless and keep you always," may you "know the truth," be righteous, upright, and true and "stay forever young." For as he wrote earlier, "He not busy being born/ Is busy dying."

"Sign on the Cross" (1967), perhaps Dylan's most enigmatic song, says that the sign on Jesus' cross can never be forgotten—"And it's still that sign on the cross/ That worries me." Men cannot escape that symbol and what it means.

"Knockin' on Heaven's Door (1972) deals with death. "I Threw It All Away" (1969) points to love as the ultimate force for good in the world. "Oh Sister" tells of dying, being reborn, and being "mysteriously saved." "Shelter From the Storm" finds Dylan wearing a crown of thorns and bargaining for salvation. "Long Ago, Far Away" (1962) warns that those who promote brotherhood might end up hanging on a cross. "Isis" (1975) speaks of quick prayers that easily satisfy. Priests recite "prayers of old" as the face of God appears in the streets in "Romance in Durango" (1975). "Joey" (1975) pictures a God of retribution who will punish evil acts.

Bob Dylan pioneered the message song; he remains at its forefront. He asks metaphysical questions and tries to give some answers, which are less than Christian. But he has affected many young people and continues to do so. We need to understand what kind of spiritual guidance he gives.

This article originally appeared in the December 3, 1976, issue of Christianity Today. At the time, Daniel J. Evearitt was assistant pastor of Tappan Alliance Church in Tappan, New York. He is now professor of religion and theology at Toccoa Falls College in Toccoa Falls, Georgia.

Copyright © 2001 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere

Christianity Today's other articles on Bob Dylan include:

Watered-Down Love | Bob Dylan encountered Jesus in 1978, and that light has not entirely faded as he turns 60. By Steve Turner (May 24, 2001)

Bob Dylan Finds His Source | A call into the bars, into the streets, into the world, to repentance. By Noel Paul Stookey (Jan. 4, 1980)

Not Buying into the Subculture | Slow Train Coming reveals that Bob Dylan's quest for answers has been satisfied. By David Singer (Jan. 4, 1980)

Has Born-again Bob Dylan Returned to Judaism? | The singer's response to an Olympics ministry opportunity might settle the matter once for all. (Jan. 13, 1984)