Although there is room for debate, probably the most significant ongoing religion news story of the past decade has been the revolution that is proceeding along several fronts inside the Roman Catholic Church. In the first half of the decade matters of structure got a lot of attention, mostly by reform-minded activists and leadership ranks. But those issues have been all but silenced of late as the revolution has quietly moved ahead on the spiritual front, engulfing hundreds of thousands of grass-roots Catholics.

These people prefer to call it renewal rather than revolution. In a recent cover story. Time called it “a kind of spiritual second wind” for the Catholic Church, evidenced in such developments as the charismatic movement, prayer and Bible-study groups, a “new spirit of voluntarism,” a vigorous resurgence of student piety, and unusually strong support for Catholic education.

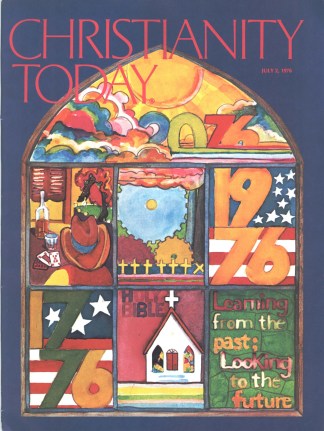

Perhaps the most remarkable of these developments is the rise and rapid growth of the charismatic movement, institutionalized somewhat by its leaders as the Catholic Charismatic Renewal (CCR). The Renewal began in 1967 among a small group of young adults on the Duquesne University campus in Pittsburgh. Today it encompasses between 600,000 and 750,000 in America and maybe that many more overseas. Indeed, within the next decade or two Latin American Catholicism may become predominantly charismatic.

Unlike some sectors of charismatic Protestantdom, the emphasis within the CCR is not so much on spiritual gifts as on nurturing a personal relationship with Christ and on developing Christian community.

For the most part, America’s Catholic bishops have remained aloof, nervously observing from a distance. A few years ago they established a liaison to keep in touch with the movement, and more recently a study committee gave it a fairly clean bill of health. As a result, a warming trend may be under way. Last year the Pope sort of gave his blessing. In late May, Archbishop Joseph L. Bernardin, president of the U. S. Catholic bishops’ conference, was the keynote speaker at the rain-drenched annual conference of the CCR at Notre Dame University in South Bend, Indiana. He told the some 30,000 participants (including about 600 priests) that he had come to give both personal and official encouragement to the movement.

Bernardin said he has seen “much good coming from this movement.” The Scriptures, said he, have become for so many what they should be—loving and living words from a loving Father.” He also indicated he was impressed by the place of prayer in the lives of adherents, by the “healing power of God” at work in them, and by the depth of their spiritual life.

While most of his speech was warmly pastoral and commendatory, there were some words of caution and some reminders about observing Catholic doctrine. He acknowledged that the existence of so many different denominations is “a scandal.” But, said he, “serious divisions do exist, and they will not go away by pretending they are not there. Much reconciliation and healing must take place on many levels before authentic unity can be achieved. It will not serve the work of church unity to compromise your own beliefs or to submerge your Catholic identity.”

On the topic of being baptized by the Spirit, he reminded: “Theologically we know that this is not the first time that a person receives the Holy Spirit” (Catholicism teaches that the Holy Spirit is imparted in water baptism). Relatedly, he said that talk of being born again (as is frequently the case in Catholic circles these days) is not correct theologically, because “that [experience] takes place through the sacrament of Baptism.”

The ecumenism caution may have been in order from the bishops’ point of view. On the program at Notre Dame were Anglican priest Michael Harper, Lutheran Larry Christenson, American Baptist Ken Pagard, and independent Bob Mumford, among others. And next year’s CCR conference will be an ecumenical one, to be held July 20–24, 1977, in a Kansas City stadium and expected to attract 60,000 persons.

Unity was one of the recurring themes of the conference, underlined by Protestant and Catholic speakers alike. Father Michael Scanlan, president of Steubenville (Ohio) College and chairman of the chief planning unit of the CCR. declared that there is no such thing as an isolated individual in the kingdom of God. Each is dependent on the others, he asserted. He went on to stress the need for unity, particularly within the Catholic charismatic prayer communities (most Catholic charismatics belong to one). Growth and strength stem from unity, he implied.

It rained all weekend at Notre Dame, marring the plenary sessions in the stadium, but spirits remained high, especially with the spirited singing of “Alabare” (pronounced ah-lah-bah-ray, meaning “I will praise”) by the hundreds of Latin Americans wherever they went.

The participants came from more than forty nations. One of the largest groups came from Puerto Rico. They were led by Father Tom Forrest, pastor of an 18,000-member mostly charismatic parish. Forrest says that almost all Puerto Rican cities have prayer groups (100 priests are in the movement) and that there are fourteen retreat centers providing direction to the Renewal. Numerical growth has been so rapid, however, that leadership and facilities have lagged, he said.

Growth is a characteristic of the Renewal virtually everywhere. A CCR directory lists 2,400 prayer groups in North America and more than 1,600 other ones in about eighty countries. A booklet for those desiring to be baptized in the Spirit is selling at the rate of 12,000 copies a month. As of three or four years ago Auxiliary Bishop Joseph McKinney of Grand Rapids, Michigan, was the only bishop in the movement. Now other bishops from North America and bishops from Belgium, Brazil, Colombia, Panama. Guatemala, Honduras, Venezuela, Japan, and Fiji are personally involved.

Ralph Martin, a Campus Crusade- and Navigators-trained founder of the movement, told the people at Notre Dame that the charismatics are “the leaven which God has placed in the dough of the church.” The leaven will spread throughout the church, he stated, and will renew it.

That’s revolutionary talk.

Timor Revisited

Although the revival of the mid-sixties touched much of Indonesia, most of the subsequent publicity—including several books—focused on the island of Timor near the eastern end of the archipelago. B. Meroekh, a leader in that revival and a senior pastor and former chairman of the synod of the 650,000-member Timorese Evangelical Church (TEC), said the churches were unprepared to do adequate follow-up. As a result, he said, the revival aftermath largely deteriorated into erroneous emphases by “over-zealous” workers.

Meroekh attended the 1974 International Congress on World Evangelization. When he returned home, he convinced church and government leaders that it was once again God’s time for Timor and surrounding islands.

To help get things going, evangelist Stanley Mooneyham of World Vision International and Indonesian Bible-school leader Petrus Octavianus, whose students figured centrally in the revival, were invited to conduct an eight-day crusade in May in Kupang, Timor’s capital city (population: 50,000).

The TEC gave official backing. Synod chairman Max Jacob said the church made follow-up a priority.

While war raged on the border 250 miles away, large crowds attended the crusade meetings, and the stadium was packed to SRO capacity of 50,000 at each of the final two meetings. There were so many responses at every meeting, say crusade officials, that counseling had to be done en masse. Among those attending was provincial governor El Tari. He declined a platform seat. “I want the eyes of the people to be on God, not on some political figure,” he explained.

Jacobs says the TEC has plans for evangelistic efforts on other islands. As for Timor: “The miracles of this crusade have been in the hearts and lives of the people,” remarks Meroekh.

Death In The Street

Don Bolles, 47, the award-winning Phoenix investigative reporter fatally injured last month by a bomb planted in his car, was the son of the late Donald C. Bolles, public relations director for the Federal Council of Churches and its successor, the National Council of Churches, from 1948 until 1959.

Political columnist Bernie Wynn wrote of his fellow staffer at the Arizona Republic. “Despite his cynicism—part of it merely a reporter’s protective coloration—Don has developed a pretty solid spiritual foundation, serving at one point as president of his [United Methodist] church’s board of directors. Another colleague quoted him as saying, “The only things I believe in are God and children.”

Among survivors are his wife, seven children, mother, sister, and a brother who is an Episcopal priest in San Francisco.

The Kgb At Work

A Russian Orthodox priest and a lay colleague who converted from Judaism are said to be targets of the latest discrediting campaign by the KGB, the Soviet secret police. The pair described their trials in an open letter to the Orthodox patriarch in Moscow. A copy of the letter was made public in the West by Michael Bourdeaux, head of the Center for the Study of Religion and Communism in Keston, England.

The priest, Gleb Yakunin, and the layman, Lev Regelson, had detailed the persecution of Christians in the Soviet Union in a document reproduced by the African organizers of the 1975 World Council of Churches assembly at Nairobi. Yakunin and Regelson contend that the document embarrassed the Soviet government and that the the KGB is attempting reprisal.

They charged that a priest at Pushkino, near Moscow, tried to collect signatures for a statement that criticized the two, describing them as purveyors of false information who are attempting to stir up discord against the Helsinki Agreement. What use will be made of the document was still unclear last month.

Religion In Transit

By a unanimous vote, the United Methodist Church’s curriculum unit declined to approve as an alternate resource confirmation materials produced by the Good News evangelical caucus. The committee said there are “many points of view within the denomination to which we should be open,” hence only UMC-produced materials are acceptable.

American Indian Movement leader Dennis Banks says he will pay back the $10,000 forfeited by United Methodist agencies when he jumped bail while awaiting trial on assault charges in South Dakota. He claims he would have been killed had he gone to jail in that state. Seeking refuge in Oregon, he says proceeds from a movie will be used for repayment. As for religious affiliation, Banks states he is a member of the Sun Dance faith.

Major-league baseball players are turning out in record numbers for Sunday chapel sessions (373 for 21 teams on a recent Sunday; Cincinnati, Montreal, and the Chicago Cubs led with 35, 30, and 28, respectively).

Regardless of church or religious ties, most Americans do not turn to God in times of tragedy, according to a nationwide study by sociologists Andrew Greeley and William McCready of the National Opinion research poll. Only about 22 per cent of respondents said they counted on God to help them with their suffering.

Canadian Keswick Conference has gone bankrupt, and friends of the deeper-life teaching center are making a last-ditch attempt to raise $1 million, a third of it in cash, to reacquire the assets before they are disposed of.

Fire last month destroyed the main administrative building of the Bibletown Community Church and Conference Center, in Boca Raton, Florida. The building housed a Christian school, a church facility, a 400-seat auditorium, a large dining hall, a bookstore, and administrative offices.

A new Census Bureau report indicates that if current trends continue, 17 per cent of America’s population will be 65 or older by the year 2030 (the figure is 10.5 per cent now).

A $5 million privately financed Jewish chapel will be built at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. Last term there were thirty-three Jews among the 4,400 cadets. They were joined by seventy Jewish officers, enlisted men, and dependents for Friday-night services in a chemistry lecture hall.

Stockholders of General Motors rejected a church-group sponsored resolution that would have made GM’s “present and future operations in Chile contingent upon that government’s commitment to honor basic workers’ rights throughout the auto industry.” Sponsored by fifteen national religious agencies, the resolution received a vote of 4.3 million shares, about 2 per cent of the total.

Nurse Gertrude Friesen of Swan River, Manitoba, became the first person granted exemption by the provincial labor board from joining a union and paying dues for reasons of conscience. A member of the Evangelical Mennonite Church, Mrs. Friesen said she objects to the union because it accepts the principle of force as a major tactic in negotiating with employers, something she cannot be part of as a Christian.

The movie version of Hugh Schonfield’s The Passover Plot has been causing a stir in Israel, where it was filmed, and it may generate a lot of controversy in the United States, where it is to be released this month. A group of Jerusalem clergymen say the film “direct[ly] attack[s] Jesus Christ … in such a way as to destroy the whole basis of the Christian faith.” They urged Israel to ban the filming. The Lutheran Church of the Redeemer in Jerusalem refused to allow filming of trial scenes in its building. The film depicts Jesus as an angry political revolutionary who was unexpectedly killed while trying to feign death.

Korean churches in the Los Angeles area have increased from 5 to 110 in the last ten years, reports correspondent Tom Steers. Most of last year’s crop of 28,000 Korean immigrants settled there, bringing the community total to 100,000.

The Canadian Society of Muslims says it will lodge a complaint to the United Nations’ human-rights commission concerning alleged discrimination against Islam in school textbooks in Ontario.

Marriages in the United States in 1974 totaled 2.2 million, a figure 54,000 lower than the preceding year’s; this was the first decline in marriages in sixteen years, according to a government study. The decline continued in 1975: early reports indicate 2.1 million marriages.

It’s time to debunk dangerous beliefs in astrology, faith healing, UFOs, reincarnation, exorcism, and ghosts, says the American Humanist Association. The AHA has appointed a group of intellectuals to its new Committee to Scientifically Investigate Claims of Paranormal and Other Phenomena to do exactly that.

World Scene

Mitsuo Fuchida, 73, Japanese commander of the air strike against Pearl Harbor in 1941, died of diabetes in a Tokyo hospital. Converted in 1950, Fuchida became a widely known Christian evangelist, sometimes teaming up with Jake DeShazer, an American who bombed Tokyo and who become a Christian in a Japanese POW camp. DeShazer is now a missionary in Japan.

The General Synod of the Church of Ireland (Anglican) by a large majority approved in principle the ordination of women to the priesthood. The Irish Methodist Church and the Irish Presbyterian Church earlier endorsed women’s ordination. Presbyterian Ruth Patterson, an assistant pastor of a church in Larne, was the first woman in her denomination to be ordained.

While Dutch clairvoyant Gerald Croisset 67, was visiting Tokyo for a TV appearance he heard about a seven-year-old girl who had been missing for almost a week. Claiming to possess ESP, Croisset sketched a map and objects that the TV people recognized. A TV crew hurried to a reservoir early the next day and found the girl’s body floating near some rowboats. Police (700 were searching for her) write it all off as a coincidence.

Italy’s Radical Party accused the parish priest in the town of Sora of campaign dirty tricks. Party spokesmen claim he kept his church bells ringing during one of its rallies, drowning out the speakers. They’re pressing criminal charges.

A high-level Catholic-Anglican study commission has recommended that the Catholic Church ease its rules governing marriages between the two faiths. Changes would allow clergy of either church to perform the ceremony, eliminate the requirement of an explicitly Catholic baptism and upbringing of children, and possibly make way for a more liberal stance on divorce and remarriage.

The new chief justice of Japan’s Supreme Court, Ekizo Fujibayashi, 68, is described in news accounts as “an ardent Christian.” He is a member of the 50,000-member “non-church” movement, a body employing non-traditional forms of church life in an attempt to duplicate New Testament patterns. Many influential Japanese Christians are members of this group.

The Buddhist government of Burma has granted permission for the printing of 5,000 copies of a Bible correspondence course, 7,500 copies of material designed to show how to become a Christian, and 30,000 copies of a letter to be used in replying to people who respond to a radio broadcast beamed by the Far East Broadcasting Company, according to a report of the Pennsylvania-based Christian Literature Crusade.

When death occurs in the Japanese underworld, colleagues of the deceased frequently sponsor elaborate funeral services in a Buddhist temple—as a cover for raising funds and rattling the sabers in a show of power. Last month, under police pressure, the 3,000 delegates at the All-Japan Buddhist Conference called for a ban of such temple use by gangsters. The action affects about 7,000 temples throughout the country. Buddhist leaders agreed to do their best but said it will be difficult to keep the bad guys out.

Chile aftermath: The Evangelical Lutheran Church, once 25,000 strong, is down to five congregations and about 1,500 members. Most ELC members departed to form the Lutheran Church of Chile in a row over statements and activities by then ELC bishop Helmut Frenz on behalf of political refugees following the 1973 military coup.