The following account is based on reports filed by correspondent Stephen Sywulka in Guatemala City, an interview with a mission official conducted by correspondent Robert Niklaus, summaries by Religious News Service and other news agencies, and releases by mission and relief agencies. It was written by associate editor Arthur H. Matthews.

Shortly after 3 A.M. on February 4, an earth tremor awoke Bill and Rachel Vasey, Primitive Methodist missionaries in Joyabaj, Guatemala. Instinctively, they ran for the door. They got out of the room just in time. Central America’s worst recorded earthquake caused the walls to cave in, crushing their bed.

In a guest room were two visitors from their mission board. They remained in bed, and after the initial shock the space separating their beds was filled with rubble and walls were gone on the sides of the beds. But neither the Vaseys nor their guests were injured.

The story could be repeated over and over as the more than 300 North American missionaries in Guatemala reported to their home agencies that they were safe. Not a single missionary was known to have been injured seriously in the earthquake that took the lives of over 17,000 Guatemalans.

The Vasey’s children, along with sons and daughters of many other missionaries, were not at home when the house was destroyed. They were all safe in the mission boarding school at Huehuetenango, which was not damaged.

The earthquake, followed by as many as five hundred aftershocks, was described by U. S. Ambassador Francis Meloy as “the greatest disaster that has befallen central America in recorded history.” The first tremor registered 7.5 on the Richter scale. The most populous part of the nation of about 5.5 million—an area around the capital city of Guatemala and extending northeast to the Gulf of Mexico—was affected.

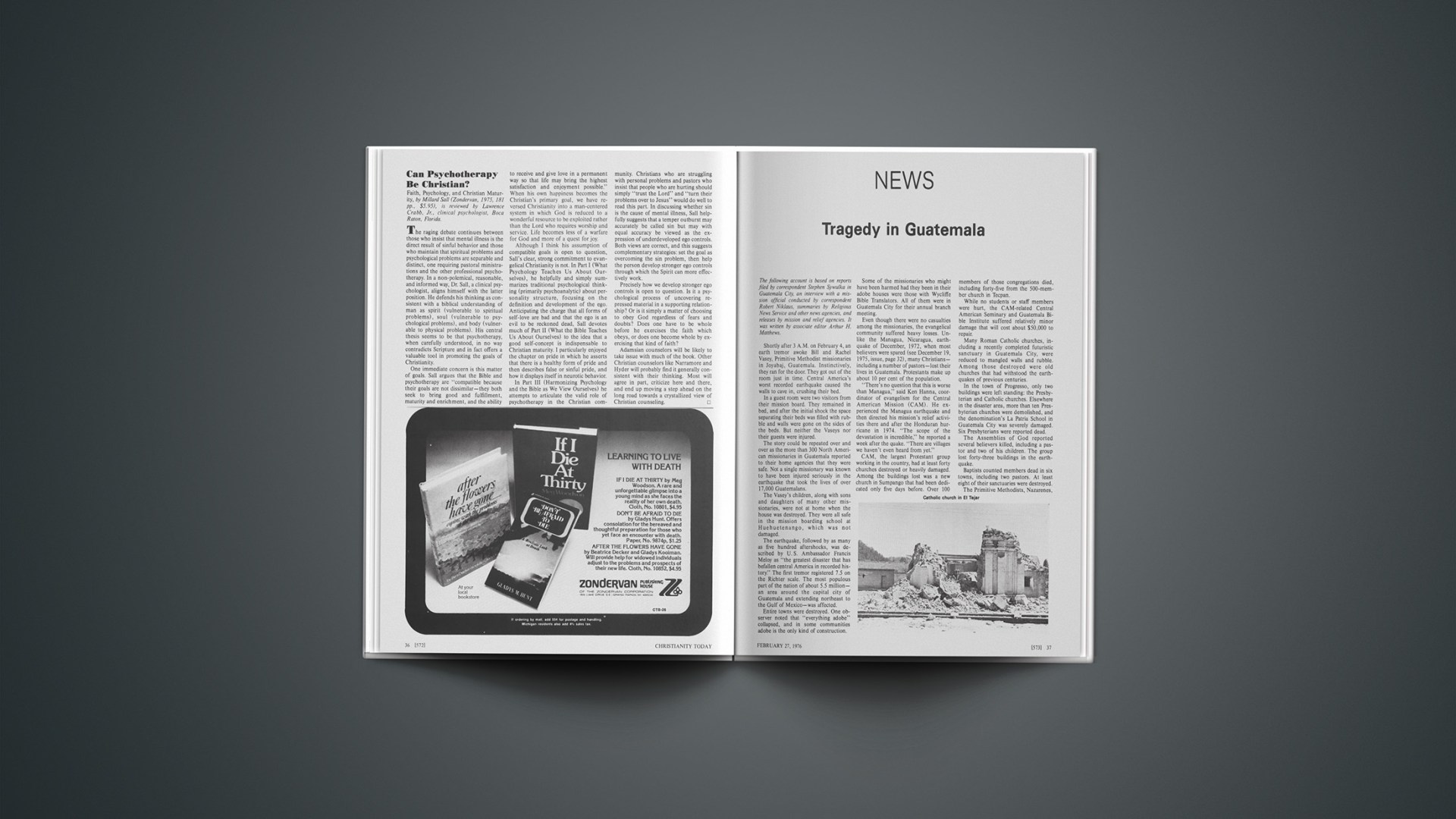

Entire towns were destroyed. One observer noted that “everything adobe” collapsed, and in some communities adobe is the only kind of construction.

Some of the missionaries who might have been harmed had they been in their adobe houses were those with Wycliffe Bible Translators. All of them were in Guatemala City for their annual branch meeting.

Even though there were no casualties among the missionaries, the evangelical community suffered heavy losses. Unlike the Managua, Nicaragua, earthquake of December, 1972, when most believers were spared (see December 19, 1975, issue, page 32), many Christians—including a number of pastors—lost their lives in Guatemala. Protestants make up about 10 per cent of the population.

“There’s no question that this is worse than Managua,” said Ken Hanna, coordinator of evangelism for the Central American Mission (CAM). He experienced the Managua earthquake and then directed his mission’s relief activities there and after the Honduran hurricane in 1974. “The scope of the devastation is incredible,” he reported a week after the quake. “There are villages we haven’t even heard from yet.”

CAM, the largest Protestant group working in the country, had at least forty churches destroyed or heavily damaged. Among the buildings lost was a new church in Sumpango that had been dedicated only five days before. Over 100 members of those congregations died, including forty-five from the 500-member church in Tecpan.

While no students or staff members were hurt, the CAM-related Central American Seminary and Guatemala Bible Institute suffered relatively minor damage that will cost about $50,000 to repair.

Many Roman Catholic churches, including a recently completed futuristic sanctuary in Guatemala City, were reduced to mangled walls and rubble. Among those destroyed were old churches that had withstood the earthquakes of previous centuries.

In the town of Progresso, only two buildings were left standing: the Presbyterian and Catholic churches. Elsewhere in the disaster area, more than ten Presbyterian churches were demolished, and the denomination’s La Patria School in Guatemala City was severely damaged. Six Presbyterians were reported dead.

The Assemblies of God reported several believers killed, including a pastor and two of his children. The group lost forty-three buildings in the earthquake.

Baptists counted members dead in six towns, including two pastors. At least eight of their sanctuaries were destroyed.

The Primitive Methodists, Nazarenes, Friends, Foursquare, and independent and Pentecostal groups also reported property and human losses.

A Christian and Missionary Alliance church in the capital city was not destroyed, but the earthquake picked up the 400-seat sanctuary and moved it three inches off its foundation.

By 3:45 A.M., the first radio station was on the air, and it was broadcasting hymns and passages of Scripture. The station, signing on an hour and forty-five minutes earlier than usual, was TGNA, an affiliate of CAM. For four hours it was the only station operating in Guatemala City. And for two days it was one of only two stations broadcasting information from the government network, including many personal messages to families about the condition of their separated members. As more stations returned to the air, they were all put on the network.

Without making a public appeal, TGNA collected relief supplies that were distributed to some twenty towns by the staff and volunteers from CAM churches and the seminary. TGBA, the mission’s Indian language station, is located at Barillas, in an area not affected by the earthquake. Its personnel staged a marathon appeal for relief. On the first day, 629 Indians came in with $374. In the area served by TGBA the Indians have an average daily income of thirty-five cents. The donors, mostly Christians, also brought more than 5,000 pounds of corn and other food to the station. Some walked several hours over mountain trails to bring their gifts.

The relief effort that began with Christians in Guatemala soon attracted help from many parts of the world. Within a week, it was estimated that supplies worth $15 million had been shipped to the devastated areas.

Some fifteen outside agencies and twenty-one denominations within Guatemala were cooperating in CEPA (the Spanish acronym for Permanent Evangelical Committee for Aid). The committee was organized two years ago in the aftermath of disasters in neighboring nations. A similar group was organized by CAM churches.

Immediate aid came from Nicaragua’s CEPAD emergency group and CEDEN in Honduras. CAM congregations in Honduras sent $1,000, as did Baptist churches in that nation. Volunteer workers rushed in from Christian groups elsewhere in Central America.

Within hours of the tragedy officials of Christian agencies in North America were also surveying the needs. Immediate shipments of tools, blankets, food, and medical supplies were authorized. Appeals for earthquake relief funds went out from a variety of agencies.

Initially, relief workers faced a problem of having more material at the Guatemala City airport than they could distribute. The tremors had been so strong that many highways were destroyed and railway tracks were badly bent. Helicopters sent by the U. S. government helped with the distribution problem until roads to the interior towns were repaired.

After the first pile-up of goods was moved, it was reported that subsequent shipments were being sent quickly to rural areas of need. More than half of the supplies came from either private or governmental sources in the United States.

Executives of relief agencies began emphasizing early that long-term help will be needed by many of the communities. Instead of asking for medicine, food, or clothes, they were stressing the need for tools, shelter, and means of livelihood.

With housing destroyed in many areas of Guatemala City and in the outlying towns, thousands were sleeping out of doors. Some whose houses still stand were afraid to enter them for fear that aftershocks would topple them.

One CAM congregation that lost its building met on the first Sunday after the disaster on a basketball court. They sang, “Great Is Thy Faithfulness.”

Missionary Helen Ekstrom said after the outdoor meeting: “There was a tremendously beautiful spirit among the believers. I cried when I saw how they were not just putting up with the situation but were praising the Lord.”

Said one leader at the basketball court service: “If we are still here, it’s because God has a work for us to do.” Several conversions were reported after that service, as well as at many others in the country. Both the CEPA and CAM relief committees have stressed a strong evangelistic effort in connection with their work.

Matias Gudiel, president of the Christian and Missionary Alliance (CMA) in Guatemala, surveyed the damage in the city of Tecpan. Among the fatalities were four of the city’s six evangelical pastors. He found an elder who lost four of his children and then told those who tried to console him: “They are with the Lord; they are much better where they are now.”

At mid-month evangelist Billy Graham flew to Guatemala to offer comfort and encouragement in a talk on national radio and television.

As Guatemalans and Christian workers from abroad continued the job of burying the dead, treating the sick and injured, and rebuilding churches, they did so with a firm and positive faith.

Prayer Breakfast: Waxing Eloquent

That grinding noise in the kitchen came from a tooth that U. S. Senator Mark Hatfield had unknowingly dislodged and placed in the disposal with some orange peels. His wife Antoinette quickly filled the gaping hole with white candle wax. En route to last month’s National Prayer Breakfast, where the senator was to give the major address, the Hatfields stopped to buy some chewing gum in case the need for additional adhesive became apparent. A dentist among the 3,000 persons in attendance at the Washington Hilton Hotel assured the Oregon Republican he could not have improvised any better.

Hatfield, who said he had been praying for humility, delivered his speech without a hitch—or smile. It was a sobering call for spiritual revolution. (The address is scheduled for publication in the March 26 issue of CHRISTIANITY TODAY.)

President Ford spoke also. He said that many times since becoming Chief Executive he has derived strength from Proverbs 3:5 and 6. “Often as I walk into my office,” he said, “I realize man’s wisdom is not enough.”

The breakfast drew evangelical leaders and businessmen from all over the country. Many diplomats and government officials also were on hand, including Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. The event is put on each year by the House and Senate prayer-breakfast groups with help from a low-profile organization formerly known as International Christian Leadership but currently referred to as simply “the Fellowship.” A letter of invitation spoke of the need for reconciliation and unity, and described the breakfast as an opportunity for “building stronger links of friendship on a spiritual basis.”

Congressman James W. Symington of Missouri, an Episcopalian, made his debut as a soloist with a black choral group from St. Louis. He sang a song that he and his wife had written, “It Takes Time to Know a Country.”

A prayer for national leadership was given by U. S. Treasurer Francine Neff, and Secretary of the Interior Thomas Kleppe pronounced the benediction.

DAVID E. KUCHARSKY

Tackling The Pros

Tackling professional football players for Christ has been one of the goals of such Christian organizations as the Fellowship of Christian Athletes (FCA) and Athletes in Action (AIA), the athletic arm of Campus Crusade for Christ. Both groups work mainly with college athletes. But the pros need Christ, too, theorize leaders. And when well-known players are recruited for Christ, they point out, there are some great fringe benefits for the Christian—and organizational—cause. As guest speakers, the pros command a wide hearing, and their Christian testimonies carry special weight, especially among young people. Understandably, the competition among sports ministries seeking to sign up the superstars has been fierce on occasion.

About two years ago, ten professional football players met in Chicago and issued a statement of concern about the “lack of communication” between these ministries, and they called for a more cooperative effort in sports outreach. The statement was aimed primarily at the FCA and AIA. A number of pros also were involved in Ira Lee “Doc” Eshleman’s Sports World Chaplaincy. But that ministry was winding down following Eshleman’s announcement that he was retiring as pro football’s first full-time chaplain.

The ten players added that they didn’t want to be identified exclusively with any of the existing ministries. Instead, they wanted to establish a movement of their own that would complement the work of the other groups. Yet they wanted to be free to work with the others if they chose to do so.

With the help of Phoenix businessman Arlis Priest, California attorney Thomas Hamilton, and others, they organized Pro Athletes Outreach (PAO). Priest and his friends agreed to be responsible for the legal, business, and fund-raising activities of the group, while a steering committee of players directed programming. (Priest, a real estate broker and investment consultant, has had counseling ties to a number of players in recent years. He also has served Campus Crusade in important capacities.)

Norm Evans of the Miami Dolphins heads the PAO steering committee. Other members include Mike McCoy of the Green Bay Packers, Jeff Siemon of the Minnesota Vikings, Tom Graham and Andy Hamilton of the Kansas City Chiefs, Ken Houston of the Washington Redskins, Gregg Brezina of the Atlanta Falcons, and Calvin Jones of the Denver Broncos.

From its beginning, PAO has concentrated on evangelism and training. This month it sponsored a five-day conference in Phoenix. More than seventy football players attended, along with some sixty wives and other guests. The event continued a series of annual conferences begun six years ago by Eshleman. The last four conferences were run by Campus Crusade’s AIA. David Hannah, AIA director, said that these were boycotted by people associated with the FCA (an FCA official claims FCA representatives were not invited). But now, noted Hannah, bridges are being built between those working to evangelize and train the pros in discipleship.

This cheerful note was echoed by Priest at a steak dinner for 555 people, most of them Phoenix-area believers who simply wanted to get a close-up glimpse of the football huskies. “It’s a thrill to me to see directors of all these ministries gather together,” commented Priest. “We all have our own things to do.”

Priest in an interview pointed out that representatives of various sports ministries attended the conference and were given an opportunity to tell about their own work.

The conference program had a variety of offerings. Among them: a seminar on marriage and the home, conducted by evangelist Lane Adams; a workshop on how to maintain a Christian testimony in the competitive crunch, led by ex-Campus Crusade staffer Wes Neal, head of the Arizona-based Institute for Athletic Perfection; and a talk by evangelist Tom Skinner, chaplain of the Washington Redskins.

The Campus Crusade touch was pervasive. Slides, films, training materials, and evangelistic literature used at the conference were all Crusade-produced, and the conferees—armed with the “Four Spiritual Laws”—hit the streets in a Crusade-style Saturday witness outing.

An FCA leader reacted good-naturedly to the Crusade input. “After all,” he remarked privately, “Crusade’s materials are the best that are readily available.”

Many non-Christian pros and their wives are invited to attend such conferences (staked by first-time-only “scholarships” worth up to $800 or so), and some of these profess Christ. Among them are linebacker Dave Washington of the San Francisco Forty-niners and his wife, both of whom accepted Christ at a 1972 conference. Washington says that other pros are searching for spiritual satisfaction, too, and that they notice the changes in those who have followed Christ.

One of the searchers at this year’s conference was defensive tackle Ernie Holmes of the Pittsburgh Steelers. En route to the PAO meeting he stopped over in Amarillo, Texas, where he was arrested on drug possession charges. Released on $1,000 bond, Holmes—divorced and on probation from a 1973 gun charge involving assault—traveled on to Phoenix. In a closing-banquet testimony, he said he had come to the PAO conference to find himself. Optimistic friends say that with Christ’s help he did.

GENE LUPTAK

Cited

Mrs. Claire Collins Harvey, a black funeral-home operator in Mississippi, received this year’s citation award by The Upper Room, a devotional magazine. Editor Maxie Dunnam said she was cited for her leadership in the fields of human rights and the worldwide Christian fellowship.

Mrs. Harvey, a United Methodist, was Religious Heritage of America’s 1974 Woman of the Year. She is the founder of Womanpower Unlimited, and a former national president of Church Women United, and she has attended important World Council of Churches conferences (she heads a WCC committee).

She says that faith and social activism go together: “There is no effective Christian witness in the social arena unless it is rooted in the Bible, in personal experience with the Holy Spirit, and with the knowledge that Jesus Christ is Lord.”

Gunn: Taking Aim

A United Methodist pastor from Gaithersburg, Maryland, will take over the reins of Americans United for Separation of Church and State. He is Andrew Leigh Gunn, 45, who succeeds the retiring Glenn L. Archer. Gunn’s appointment effective April 1, was announced at the group’s annual meeting.

“Let the word go forth again in this bicentennial year,” Gunn said, “that Americans United is the advocate and not the adversary of religious peoples who treasure religious liberty.” He promised “no malice on our part,” but he also vowed not to “hesitate to speak out when religious freedom is in jeopardy.”

The search for a successor to Archer took more than two years. Archer had been the organization’s guiding light since its inception in 1947. Over the years, the group’s primary aim has been to prevent tax dollars from flowing to church-affiliated schools.