Once in a while it’s good to step back from day-to-day political dramas and wonder what the greatest dramatist ever would do with contemporary characters. The Bulletin interviewed political scientist Eliot Cohen—professor emeritus at Johns Hopkins University, former counselor of the Department of State, and author of The Hollow Crown: Shakespeare on How Leaders Rise, Rule, and Fall—to learn more about Shakespeare’s perspective on global strongmen. Listen to the whole conversation in episode 201. Here are edited excerpts.

What drew you to write a book about Shakespeare and power?

My wife and I were seeing Henry VIII, and there’s this great moment where Henry VIII’s minister, Cardinal Wolsey, is suddenly deposed and he doesn’t see it coming. He says,

Farewell? A long farewell to all my greatness!

This is the state of man: today he puts forth

The tender leaves of hopes; tomorrow blossoms

And bears his blushing honors thick upon him;

The third day comes a frost, a killing frost,

And when he thinks, good easy man, full surely

His greatness is a-ripening, nips his root,

And then he falls, as I do. I have ventured,

Like little wanton boys that swim on bladders,

This many summers in a sea of glory,

But far beyond my depth. My high-blown pride

At length broke under me and now has left me,

Weary and old with service, to the mercy

Of a rude stream that must forever hide me.

I heard that soliloquy and I said to myself, “I know that guy. I’ve known people in Washington like that.” I was so excited by this.

When you say you know that guy, tell me what that means to you.

I’ve seen what happens to people in high office. You get swollen with pride and ego and a sense of accomplishment. The nature of things is very precarious. And all of a sudden, you fall. You think you’re swimming in a sea of glory, but you are beyond your depth. This is what happens with Wolsey. He’s become wise too late. I’ve seen that happen to a number of people, and one of the conclusions I’ve come to over the course of a fairly long career is that power really is very bad for most people.

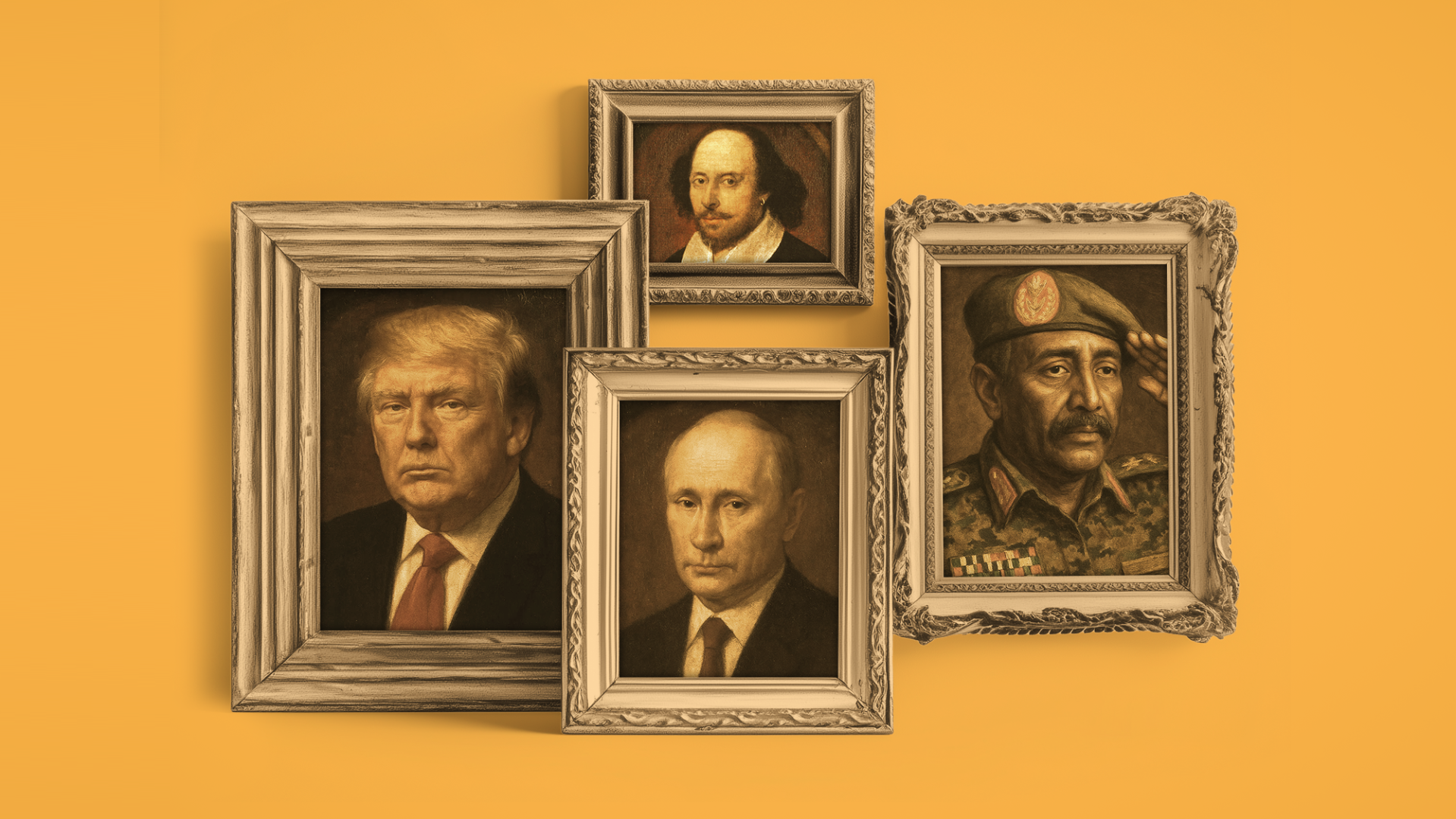

We’re living in a moment where we have more than our fair share of Shakespearean figures on the world stage: Vladimir Putin, Donald Trump, Benjamin Netanyahu, to name a few.

I’d prefer more boring times. Shakespeare portrays people, including his villains, with such vividness. Richard III is a fascinating character. He’s evil, and he can teach us a lot about evil people. He orders the big crime, the murder of his two nephews in the tower, and when his subordinate gives him a funny look, Richard says, Let me make myself plain. I want the bastards dead and wish it done suddenly.

A certain kind of authoritarian personality may start by covering their tracks, but then at some point they don’t feel they have to anymore. That was the case with Putin, and for better or for worse, we’re living in a time where these very pronounced characters are having a disproportionate effect on all of our lives.

Shakespeare is focused on personality. He doesn’t particularly focus on ideology. He was living in a somewhat ideological period between Catholics and Protestants, and I think he was being careful not to show his hand. If you made a mistake that way, you could end up in the Tower of London.

I suspect it’s also because he believes that, at the end of the day, personality and psychology and character overwhelm ideology. We’re living in a populist moment that can be ideological, but it’s also very much about the leader. Shakespeare is telling us to first look at the leading characters and then talk about ideology.

You talk a fair amount about Abraham Lincoln, who saw Shakespeare as his secular Bible, this book that he read and reread and quoted from often.

The two books that shaped Lincoln’s thinking about the world were the Bible and Shakespeare’s works. There are echoes of both in his writing and rhetoric. Shakespeare makes you question yourself and your own motivations and look within. We know that was true with Lincoln.

There’s this very haunting moment where he’s returning from Richmond after it’s been finally occupied by Union forces, and he begins reciting this passage from Macbeth to his colleagues on this steamer going back to Alexandria and then on to Washington.

Better be with the dead,

Whom we, to gain our peace, have sent to peace,

Than on the torture of the mind to lie

In restless ecstasy.

Why does that passage resonate with Lincoln? He knows he sent a lot of men off to die. He didn’t doubt the necessity of it. I don’t think he ever really second-guessed himself in the way that some people might, but he felt the penalty that you pay for that.

One of the virtues of Shakespeare is a prod to a certain kind of introspection. Along with deep-seated religious and moral belief, introspection is one of the ways that you come to know and establish yourself as a person.

Shakespeare illuminates that historical moment. Can he shed light on the changes in US politics?

One of the things Shakespeare has to teach us is empathy, and I think that is something sorely lacking now. Empathy is not the same thing as sympathy. Sympathy is “I feel sorry for you. I wish I could make things better for you.” In many cases it is a wonderful attitude to have.

Empathy is “I can imagine what it is like to be you, to really get inside your head and think like you—why you are you the way you are, why you believe and do the things you do.”

There’s this phenomenal soliloquy that Richard III gives before he’s become king where you see the roots of his insane ambition are to be king. His ambition comes from the fact that he’s physically deformed. He knows that he’s repulsive to women, that he’s not a lovable human being at all. Imagine that you really believe you are a completely unlovable person. That takes you to a very dark place very quickly. Shakespeare reveals this vulnerability as an act of empathy for a complicated figure, and he displays that great strength over and over in his work. I think we have lost that.

The second is this: We live in a world where there’s no particular reverence for actual facts. Everybody gets the right to their own truth. That’s also a path of madness, and Shakespeare speaks to that as well. Many of his characters come to grief because they’re fantasists.

Unfortunately, whether because of social media or other reasons, people want to believe their own truths. Within the American context, you have narratives like the 1619 Project—that the entire American project is fundamentally about slavery. Then you have the Trump administration trying to thoroughly whitewash American history in which there is no Trail of Tears or slavery. That’s rubbish too. Shakespeare reveals the folly of this kind of thinking.

In your book you say that Brutus is right—the murder of Julius Caesar was a savage betrayal—and the conspirators were also right that Julius Caesar was a looming tyrant. There are no simple heroes and villains in Shakespeare. They’re complex human beings.

This is part of what makes Shakespeare so compelling. The characters are always changing. It’s amazing to me: In two to three hours on a stage, you can see a human being evolve in a thoroughly fascinating way. We sometimes miss that, particularly when we talk about political figures. While people’s characters do get formed by the time they’re in their 20s or 30s, they still can change throughout the rest of their lives—and they do.