Between Denial And Desire

The American public seems to vacillate between what C. S. Lewis said were two common errors: to deny the existence of Satan, and to have an inordinate interest in him. With the filming of one of this decade’s best-selling novels, The Exorcist, the two errors exist simultaneously. People who reject the Christian’s claim that Satan exists rush to view this very explicit portrayal of demonism.

William Peter Blatty’s novel is based on an actual case of demon possession. In 1949 a boy living in Mt. Ranier, Maryland, just outside Washington, D. C., became the target and abode of a demon. After somatic and psychosomatic possibilities were tested and discarded, the parents, who were Lutheran, approved their son’s conversion to Catholicism for the purpose of exorcism, a rite still practiced by the Roman church.

Blatty, who was a student at Georgetown University at the time, read of the incident in the newspaper, remembered it, and wrote his occult thriller years later. Although he made the possessed child a girl instead of a boy and relocated the scene to Georgetown near the campus of the Jesuit school, he followed closely the recorded pattern of personality disintegration. (A diary was kept of the boy’s case.) Blatty also added several subplots: a younger priest’s crisis of faith, a murder, and an elderly priest’s years-old battle with the demon.

Released last month by Warner Brothers, the film faithfully follows the novel (Blatty produced and wrote the screenplay). What is nightmarish to read becomes at times slick horror, at times painful reality on the screen. We can thank director William Friedkin—he directed The French Connection, which reaped five Academy Awards—for such cheap thrills as a vivid picture of a spinal tap. But for conveying the reality of demonic possession we must credit the acting of Linda Blair, a junior high school student from Connecticut in her first professional role.

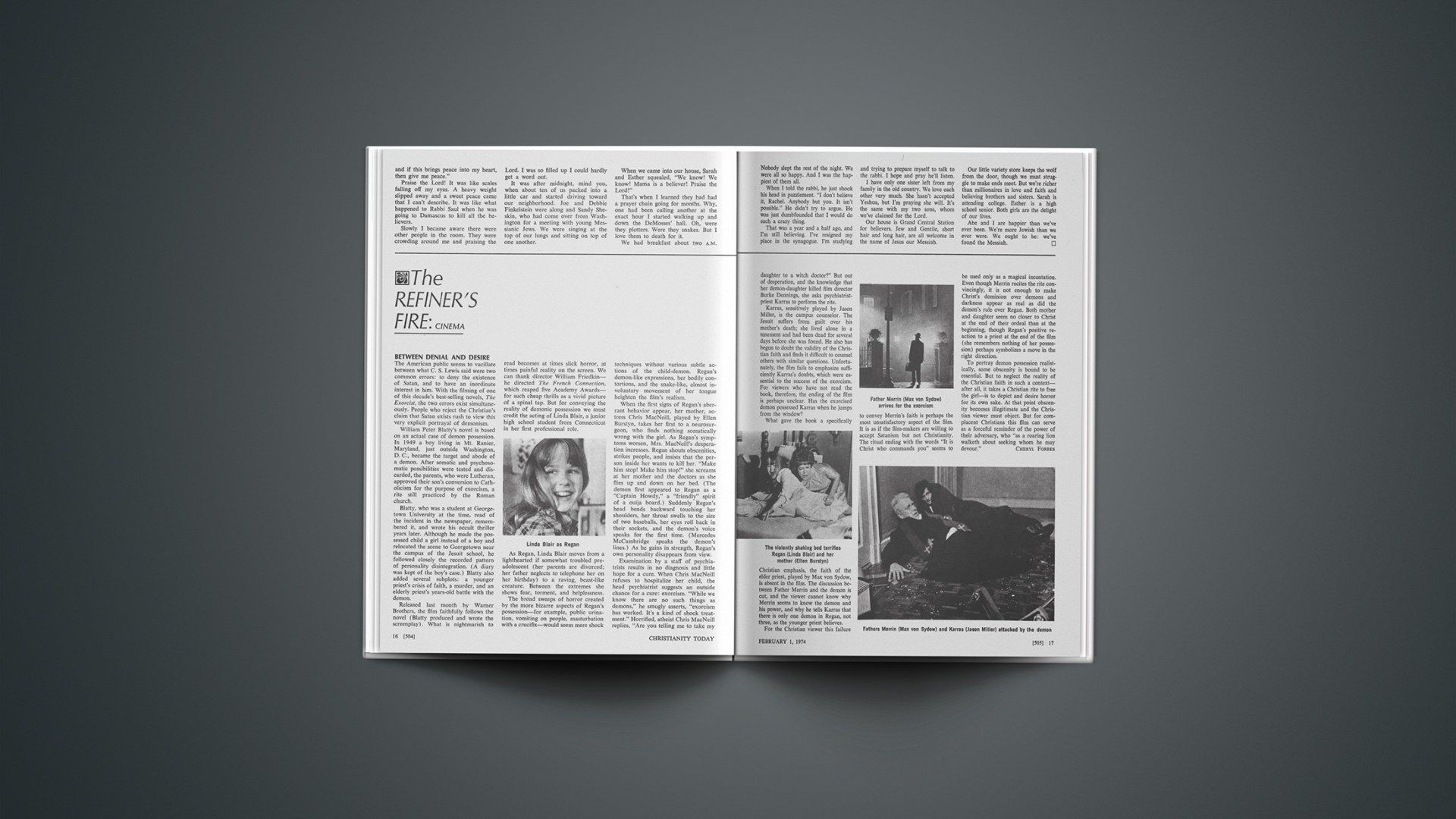

As Regan, Linda Blair moves from a lighthearted if somewhat troubled preadolescent (her parents are divorced; her father neglects to telephone her on her birthday) to a raving, beast-like creature. Between the extremes she shows fear, torment, and helplessness.

The broad sweeps of horror created by the more bizarre aspects of Regan’s possession—for example, public urination, vomiting on people, masturbation with a crucifix—would seem mere shock techniques without various subtle actions of the child-demon. Regan’s demon-like expressions, her bodily contortions, and the snake-like, almost involuntary movement of her tongue heighten the film’s realism.

When the first signs of Regan’s aberrant behavior appear, her mother, actress Chris MacNeill, played by Ellen Burstyn, takes her first to a neurosurgeon, who finds nothing somatically wrong with the girl. As Regan’s symptoms worsen, Mrs. MacNeill’s desperation increases. Regan shouts obscenities, strikes people, and insists that the person inside her wants to kill her. “Make him stop! Make him stop!” she screams at her mother and the doctors as she flies up and down on her bed. (The demon first appeared to Regan as a “Captain Howdy,” a “friendly” spirit of a ouija board.) Suddenly Regan’s head bends backward touching her shoulders, her throat swells to the size of two baseballs, her eyes roll back in their sockets, and the demon’s voice speaks for the first time. (Mercedes McCambridge speaks the demon’s lines.) As he gains in strength, Regan’s own personality disappears from view.

Examination by a staff of psychiatrists results in no diagnosis and little hope for a cure. When Chris MacNeill refuses to hospitalize her child, the head psychiatrist suggests an outside chance for a cure: exorcism. “While we know there are no such things as demons,” he smugly asserts, “exorcism has worked. It’s a kind of shock treatment.” Horrified, atheist Chris MacNeill replies, “Are you telling me to take my daughter to a witch doctor?” But out of desperation, and the knowledge that her demon-daughter killed film director Burke Dennings, she asks psychiatrist-priest Karras to perform the rite.

Karras, sensitively played by Jason Miller, is the campus counselor. The Jesuit suffers from guilt over his mother’s death; she lived alone in a tenement and had been dead for several days before she was found. He also has begun to doubt the validity of the Christian faith and finds it difficult to counsel others with similar questions. Unfortunately, the film fails to emphasize sufficiently Karras’s doubts, which were essential to the success of the exorcism. For viewers who have not read the book, therefore, the ending of the film is perhaps unclear. Has the exorcised demon possessed Karras when he jumps from the window?

What gave the book a specifically Christian emphasis, the faith of the elder priest, played by Max von Sydow, is absent in the film. The discussion between Father Merrin and the demon is cut, and the viewer cannot know why Merrin seems to know the demon and his power, and why he tells Karras that there is only one demon in Regan, not three, as the younger priest believes.

For the Christian viewer this failure to convey Merrin’s faith is perhaps the most unsatisfactory aspect of the film. It is as if the film-makers are willing to accept Satanism but not Christianity. The ritual ending with the words “It is Christ who commands you” seems to be used only as a magical incantation. Even though Merrin recites the rite convincingly, it is not enough to make Christ’s dominion over demons and darkness appear as real as did the demon’s rule over Regan. Both mother and daughter seem no closer to Christ at the end of their ordeal than at the beginning, though Regan’s positive reaction to a priest at the end of the film (she remembers nothing of her possession) perhaps symbolizes a move in the right direction.

To portray demon possession realistically, some obscenity is bound to be essential. But to neglect the reality of the Christian faith in such a context—after all, it takes a Christian rite to free the girl—is to depict and desire horror for its own sake. At that point obscenity becomes illegitimate and the Christian viewer must object. But for complacent Christians this film can serve as a forceful reminder of the power of their adversary, who “as a roaring lion walketh about seeking whom he may devour.”

CHERYL FORBES