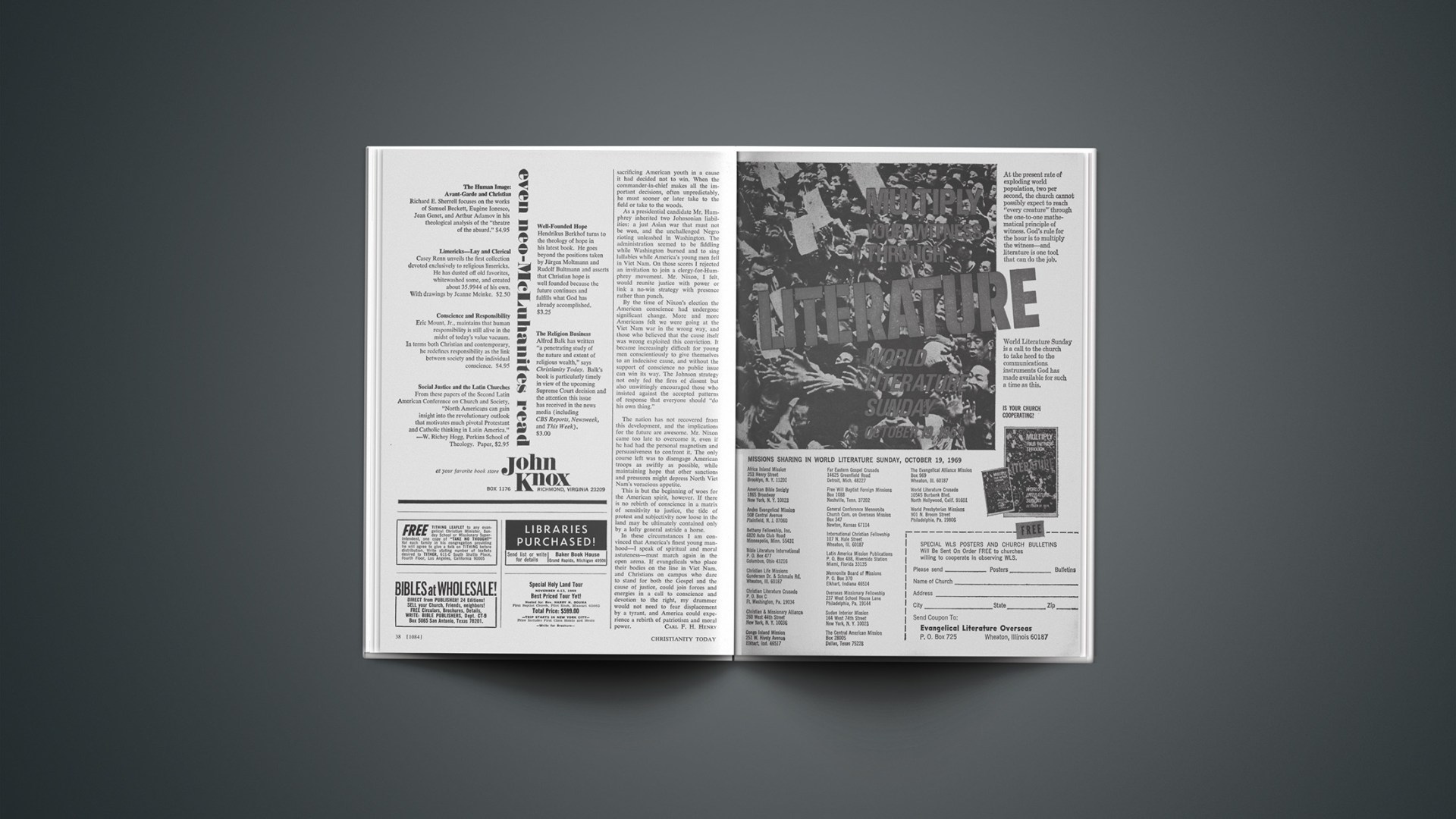

The speaker might have been Negro militant James Forman. Except that his face was not black; the state he was attacking was South Dakota; and instead of a beard, his distinctive marks were a red jacket and a beaded headband.

He is Dennis Banks, a Minnesotan, and he does not like his American Indian Movement to be compared to the militant blacks. But the comparison is inevitable.

Like Forman, he was disrupting a church conclave—this time a meeting in Sioux Falls of some 150 Lutheran workers among the Indians. Like Forman, he is seeking civil rights for his people. And his words, like Forman’s, carry a sting.

“You tell me Christianity is a good religion—the best,” he declared. “But if so, why aren’t Indians in your churches?… This is America’s most racist state.… Justice: the whites spell it ‘Just Us.’ ”

The delegates reacted sympathetically, assuring the Indians they would have more influence within the three major Lutheran bodies. More significant, however, was what the confrontation symbolized: Indian culture and religion in the midst of change.

For decades the American Indian population has been growing rapidly, and it now numbers about 700,000.1Government Indian raids in the late 1880s dedmated the nation’s Indian population, leaving only 250,000. It once had been one million. Two-thirds live on reservations in the poor-land areas of the West, where they were driven a century ago.

As a class, they are poor, with a median per-capita income of about $800 a year (several times smaller than that in the Los Angeles Watts area). They are still mainly rural, though there is a growing shift toward the cities. They are young; more than half are under twenty. Their birth rate is twice that of the rest of the population.

During the years of increasing Indian population, most Indian missions have developed along traditional lines. Preaching has been central. Many churches, particularly the more liberal ones, have carried on rudimentary social programs. But in nearly every case, the white man has “run things” for the 50 per cent of America’s Indians who are at least nominally Christian.

Now shifts within Indian culture are pounding against this framework. A new self-awareness has developed, chiefly through the movement of Indians to the cities. Minnesota Indians describe Minneapolis as their “biggest reservation.” Observers in the Southwest, where the largest share of the Indians live, talk of “substantial numbers going urban.” All major cities report growing Indian ghettoes (there are 26,000 Indians in New York, for example).

As they have moved, Indians have become more keenly aware of the cultural and economic differences between white and red people. The stark poverty of so many reservations, the coffee-and-bread diets, the junk-car homes, the high infant-mortality rate—all stand out grimly against metropolitan affluence.

Increased self-awareness also has brought new understanding—and hatred—of missionary paternalism. “They remember,” said one churchman, “the white pastor making announcements as he poured the contents of the offering plate into his coat pocket.” They recall that whites always earned salaries, while many Indian ministers worked for free. They view clothing boxes as an insult because of “this thing called dignity.”

And awareness has brought to some an anger toward the white man’s indifference to Indian culture and sensitivities.

On the national level, an example of this was the reputed “perfunctory manner” in which New Yorker Louis Bruce was chosen United States Commissioner of Indian Affairs last month with almost no consultation with Indian leaders. Of churches, Charles E. Fiero of the Christian and Missionary Alliance declared bitterly: “I have seldom visited a church for Indians where the format was not predictably white.”

Perhaps, they tell themselves, it is simply that the white man never has cared about them, and still doesn’t. Gordon H. Fraser, chancellor of Southwestern School of Missions in Arizona, noted: “In the decade that we were erecting the Statue of Liberty to welcome the masses of Europe, we … exterminated 40,000 Indians because we had no room for them.”

Indians who know this often grow cynical. “I’m getting bitter,” said one youth. “And if you don’t wake up, there are going to be lots more like me.”

All of this has set off rumblings on the reservations—mild at the center, devastating on the edges.

In the heartland of some Southwest reservations, traditional evangelism is still successful. A missionary from Rockpoint, Arizona, reported that while 80 per cent in her area hold to native religions, the Christian Church is expanding rapidly. “These people are far enough from modern society [most speak no English] to avoid disillusionment,” she said.

Others in that region report strong camp meetings and growing indigenous churches. Fraser’s school maintains healthy enrollment. Many are excited about Christian Literature Foundation’s new Indian translation of the New Testament, using an 850-word vocabulary.

But nearer the fringes of the reservations, and outside the Southwest, most Indian churches are faced with the choice of changing or folding. A priestresearcher in South Dakota, the Rev. Stanislaus Maudlin, estimated that as much as 10 per cent of the Indian Christian community in the Upper Plains is leaving the church each year. Conversations with Indians back him up. Even the most optimistic church officials will say only: “Maybe we’re holding our own.”

Much of the loss is through migration to the larger cities, where Christian Indian ministries are rare. But a substantial number also leave because of disillusionment over church paternalism and hypocrisy. Father Maudlin tells of an archdeacon in the Episcopal church of South Dakota who left “because I had to choose between being in the church and being Indian.”

Another factor is the impact of native Indian cults, such as the peyote religion in the Southwest. And Mormonism is said to be making impressive inroads.

In response to these shifts, most of the groups in the National Council of Churches are making drastic, rapid changes from church-oriented, competitive ministries to ecumenical, social programs. The United Presbyterians, regarded as typical, once had thirty churches on Pine Ridge Reservation in the Dakotas; today they have four or five. Other groups, such as the Upper Midwest Lutherans, are placing more emphasis on social programs while still trying to maintain strong preaching. Most of the mainline denominations are turning leadership over to Indians (all the 113 Methodist Indian churches of Oklahoma now have Indian pastors).

Among evangelical groups, the pattern is mixed. Perhaps the Christian and Missionary Alliance’s Fiero best stated their over-all aims: “Our focus is the conversion of people to Jesus Christ, establishment of individuals in holy living, and establishment of churches. Some of our workers envision such churches as being predominantly Indian in membership, with full Indian leadership. And some of our group do not see a need of distinctly Indian church life for Indian believers. We have good, effective workers of both persuasions.”

In any case, it appears certain that all Christian agencies committed to Indian work have a lot to do—and quickly—to meet the social and spiritual needs of America’s first citizens. In another generation, it may be too late.