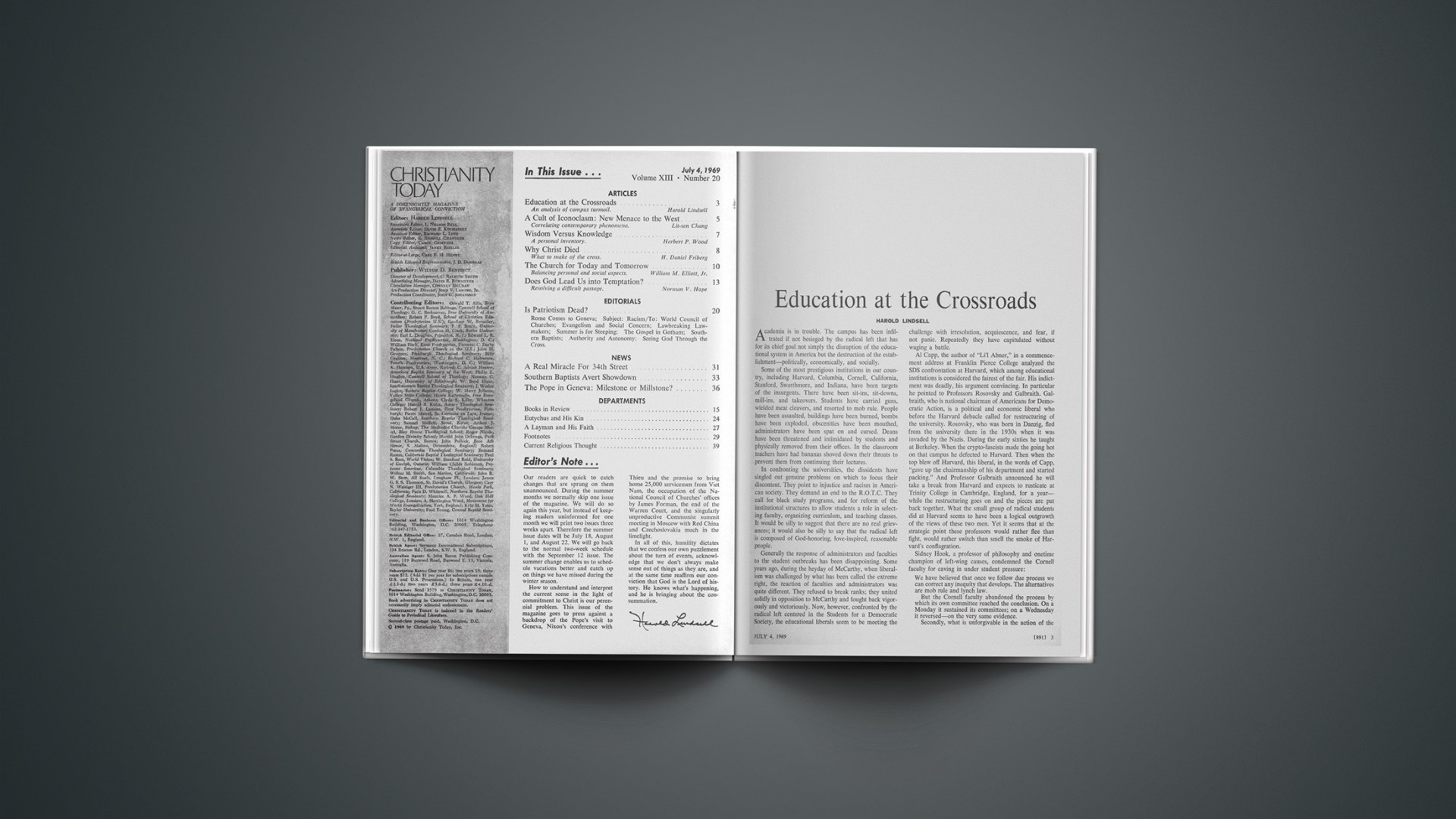

Our readers are quick to catch changes that are sprung on them unannounced. During the summer months we normally skip one issue of the magazine. We will do so again this year, but instead of keeping readers uninformed for one month we will print two issues three weeks apart. Therefore the summer issue dates will be July 18, August 1, and August 22. We will go back to the normal two-week schedule with the September 12 issue. The summer change enables us to schedule vacations better and catch up on things we have missed during the winter season.

How to understand and interpret the current scene in the light of commitment to Christ is our perennial problem. This issue of the magazine goes to press against a backdrop of the Pope’s visit to Geneva, Nixon’s conference with Thieu and the promise to bring home 25,000 servicemen from Viet Nam, the occupation of the National Council of Churches’ offices by James Forman, the end of the Warren Court, and the singularly unproductive Communist summit meeting in Moscow with Red China and Czechoslovakia much in the limelight.

In all of this, humility dictates that we confess our own puzzlement about the turn of events, acknowledge that we don’t always make sense out of things as they are, and at the same time reaffirm our conviction that God is the Lord of history. He knows what’s happening, and he is bringing about the consummation.