Dear Theological Athletes:

Among the pleasant memories that remain from a somewhat misspent boyhood are those of the Saturday nights when we would station ourselves on the hill overlooking the Armory Auditorium in hopes of watching the wrestling matches without parting with a then valuable quarter. After a few minutes of the opening match the auditorium would become uncomfortably hot and some unknown benefactor would open the large window facing the hill, giving us a clear view of the arena.

Even then it seemed somewhat strange to me that the Swedish Angel could withstand the Masked Marvel jumping full weight on his stomach without apparent injury. Or that Indian Joe could batter Kid Curly’s head against the ring post without causing a concussion.

With the advent of television and its close-up of the ring action, my suspicions became confirmed. It’s all a fake. All the mayhem that appears to be happening is just sleight of foot. And only recently has the reason for the fakery become clear to me. Wrestling is not a hostile or destructive sport. In spite of all that wrestlers do to make it look vicious, it just isn’t.

Have you ever seen two small boys trying to establish rapport with each other? They wrestle. First there’s the playful nudge. Then comes the friendly counter push. And in a moment they’re on the ground puffing, giggling, and having a beautiful time. Wrestling is the original I-Thou relationship. (As proof of my point just recall Jacob’s famous match.)

It seems inescapable to me that the sport for today’s theolog is not the popular jogging but wrestling. In fact, I’d like to suggest that planners of theological curricula include wrestling in the seminary program, with credit, of course. Think of the mutual understanding that could result from theologically oriented wrestling matches. Deacons’ meetings could be opened with prayer and closed with wrestling.

As a final contribution I’d like to offer my services in arranging matches designed to further theological camaraderie. For instance: Billy Graham vs. Jitsuo Morikawa. Or perhaps a tag-team match with Pope Paul and Cardinal O’Boyle vs. Fathers Curran and Kavanaugh. As a final nostalgic touch we could have a mystery bill with Eutychus III as the Masked Marvel vs. Penultimate as the Hooded Hurricane.

Perspiringly yours, a guest of EUTYCHUS III

Reproduction Restudied

Thank you for the thorough articles on birth control and the Old and New Testaments, also “The Relation of the Soul to the Fetus,” and the good “A Christian View of Contraception” (Nov. 8 issue). Such a study was long overdue, and was amazingly thoroughly studied and presented. Really, it should be put into reprint form.

Pear City, Ill.

As one of the participants at the Symposium on the Control of Human Reproduction, I feel obligated to inform your readers that the exegetical argument of Professor Waltke (“The Old Testament and Birth Control”) on Exodus 21:22–25 is by no means apodictic. Waltke follows the interpretation of David Mace (Hebrew Marriage), over against virtually all serious exegetes, classical and modern, in claiming that the passage distinguishes between a pregnant mother (whose life has to be compensated for by another life if killed) and her fetus (unworthy of such compensation).…

The equality of mother and unborn child in Exodus 21 is upheld not only by a classic Old Testament scholar such as the nineteenth-century Protestant Delitzsch but also by such contemporary Jewish exegetes as Cassuto, whose Commentary on the Book of Exodus (trans. Abrahams [Jerusalem: Magnes Press, The Hebrew University, 1967]) is a landmark. Here are the relevant portions of Cassuto’s explanatory rendering:

When men strive together and they hurt unintentionally a woman with child, and her children come forth but no mischief happens—that is, the woman and the children do not die—the one who hurt her shall surely be punished by a fine. But if any mischief happens, that is, if the woman dies or the children die, then you shall give life for life.

To interpret the passage in any other way is to strain the text intolerably.… The original text places a value on fetal life equal to adult life, and in doing so perfectly conjoins with the rest of Holy Writ (such as Ps. 51:5; Luke 1:41, 44).

Chairman

Division of Church History

Trinity Evangelical Divinity School

Deerfield, Ill.

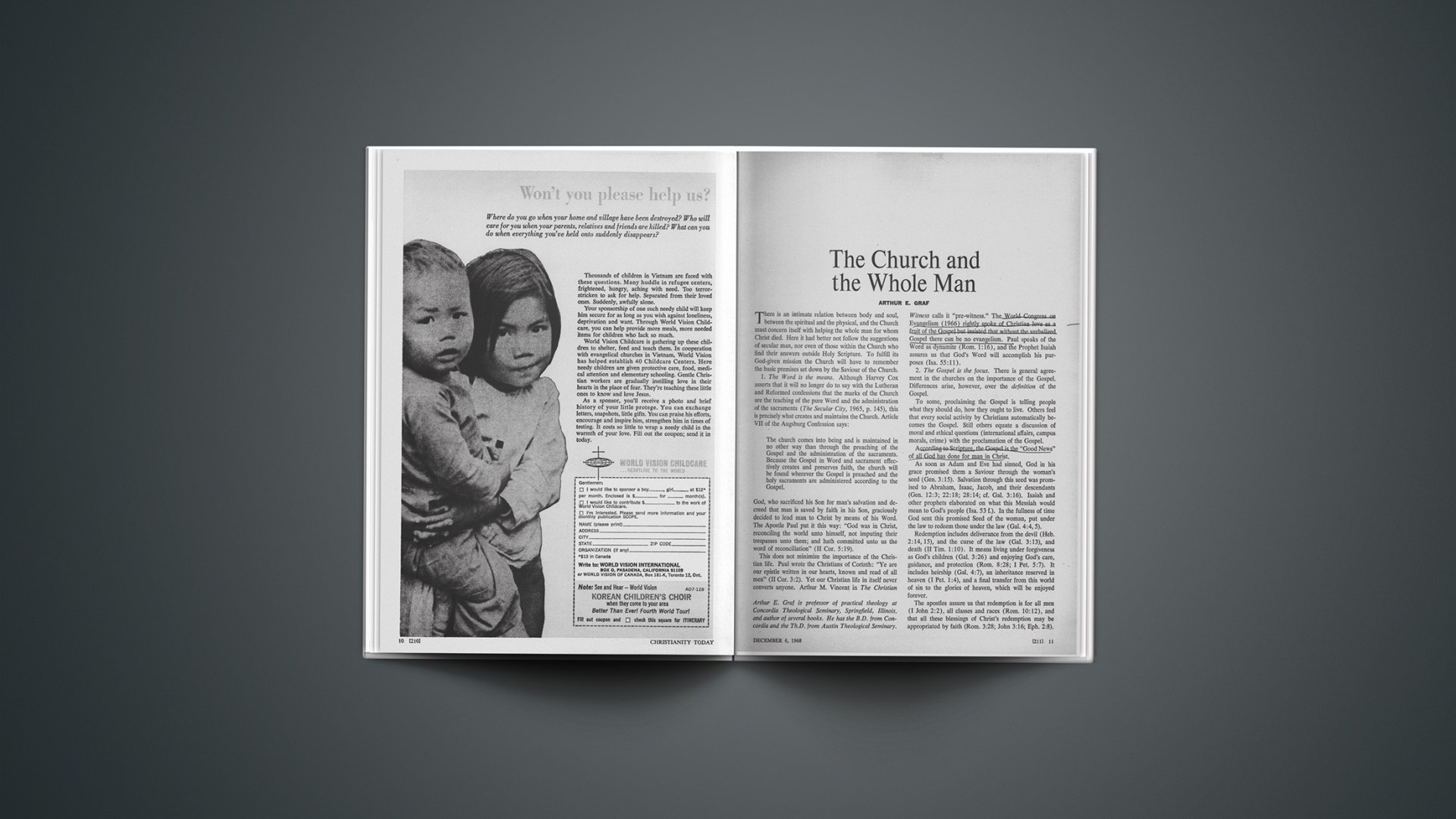

I would like to commend you highly for calling attention to the issues of “Contraception and Abortion.” I would hope that Christian young adults might seriously consider limiting their families with the thought of giving what might have been spent for the extra children to some of the starving children of the world.…

I hope that you will very forcefully remind us of the pressing problems of world population and of starvation. You might do us the favor of publishing the names and addresses of missions … who are working in areas of pressing food needs. What is our affluent American society coming to when so much money and attention is spent on luxuries that we can do without, when half the world lacks even its “daily bread”.…

Over against 130 advertisements [in a recent issue of Time Magazine] calling attention to our American wants and needs—and how few are actually needs—there was … one advertisement that called attention to the dire need of the other half of the world.…

“If a brother or sister be naked, and destitute of daily food, and one of you say unto them, Depart in peace, be ye warmed and filled; notwithstanding ye give them not those things which are needful to the body; what doth it profit?” (Jas. 2:15, 16).

History Department

Rutgers, The State University

New Brunswick, N.J.

Dr. Waltke’s argument that … the fetus cannot be considered on a par with a living person is rather incomplete. I don’t intend to teach the Bible to the good professor, but he should have cross-checked his reference with passages like Psalm 139:13–16; Jeremiah 1:5, and Galations 1:15 before coming out with such a drastic statement.

Artificial birth control and family planning, by all means, yes! However, we Christians should be extremely cautious on the matter of induced abortion, in a day when this evil is so thoroughly widespread and is reaping its harvest not only in the child but also in the mother through death or other repercussions.

Istanbul, Turkey

Are you all trying to compete with all the other bold-faced magazines on the newsstands? I was actually ashamed when this [cover] stared me in the face in our mail box and would appreciate it, if you have any more screamers like this one, please put ours in a jacket! And please don’t expect a renewal when our subscription expires.… Lots of your stuff reeks of double talk.

MRS. G. A. GARREN

Tallahassee, Fla.

Although “Therapeutic Abortion: Blessing or Murder?” (Sept 27) contains some excellent Christian insights, one might take issue with some views expressed. True, no federal law forbids abortion by name, but the Fifth Amendment guarantees due process of law before an American court can deprive one of life. A group with consultants deciding on abortion requests is not the jury that Article 3 of the Constitution requires. If an unborn child can be an heir, the law recognizes civil rights of the unborn.

Neither Catholics nor others regard a pope’s opinion on the animation of embryos as settling the issue. But they would expect the embryo to manifest definitely human acts at some future time. If the still fetus is really regarded as “an impression or figment of the imagination,” then there would be only an imaginary problem! If body, soul, and mind develop, it is reasonable to presume they are there continuously in the process.

It is the practice of many Christians to baptize a non-viable fetus, somewhat parallel to Hippocrates’ ideal that a doubtful or dying life is to be treated with the same care due to a certain and vigorous life.

Philadelphia, Pa.

Dr. Visscher is no doubt well versed in his field. But it would seem that even an average student of Scripture and logic might find inconsistencies in his approach to this subject.

First, he uses the terms “non-viable” and “viable” to distinguish the fetus before and after the quickening point in pregnancy. The dictionary defines “viable” as “capable of living and developing normally.” Now, who is going to say that the fetus in its earlier stage is any less capable of living and developing normally than in its later stage?… He is using a term which, though it may be perfectly correct clinically and medically, is totally misleading in the present ethical view.

Secondly, his treatment of the sixth commandment is somewhat less than logical. Just as it cannot logically be stretched beyond its essential meaning of “murder” or forbid the taking of all life under any condition (as in war), so neither must it be narrowed to the point of permitting “killing in love”—or in his words with “no personal hostility”.… Many highway deaths result from situations involving no personal hostility, but we cannot escape the fact that an injustice is involved nonetheless.…

The question posed in the title still remains.

Fillmore, N. Y.

Saying The Unsaid

The problem with your editorial on the student left (Nov. 8) is not what you said but what you did not say. I fear that Christians will be thereby encouraged to continue to deplore, condemn, and explain away student agitation without themselves doing much either to criticize or improve our society and its educational institutions. The New Left’s way of doing something may not be much better than our way of doing nothing, but I wonder if it is really worse.

I can speak only for certain aspects of contemporary humanistic education (how many times has this been done before?), which is, even here, so unwieldy, impersonal, and hidebound that it is a wonder that more graduates do not develop a deep hatred for “the life of the mind.” We write papers for grades, read books for finals, take courses for credits, credits for degrees, degrees for jobs or more degrees, and these in turn for money. And in this we seem to be fulfilling admirably the expectations of most of our elders, but we are not fulfilled.…

You correctly criticize the New Left’s rationale, but your neglect to mention the real problems confronting sensitive collegians will allow Christians to rationalize away, as one of your letter-writers does, the whole of student dissent. If the spirit … of intolerance and of irrationality is not to triumph in the hands of administration, faculty, and students, then Christians will have to do more than criticize the critics. Your editorial will not help them to do this, insofar as it comforts them with the illusion that the radicals are only fighting straw men.

San Diego, Calif.

From Lutherans With Love

Just a few lines to congratulate you on your perceptive coverage of the American Lutheran Church’s recent biennial convention in Omaha. I enjoyed tremendously your views of both “Luththeran Love-In” and “ALC Man to Watch” (News, Nov 8).

You’ll probably hear from others on a small typo; the ALC’s college in Minneapolis is not Augustana (that’s at Sioux Falls) but Augsburg College. It was taken over from the Lutheran Free Church when the latter joined the ALC.

Division of Public Relations

Lutheran Council

New York, N. Y.

May I, a member of Missouri Synod, comment briefly on “Lutheran Love-In.” My comment: Great!

I have only recently returned from a tour of duty on Wake Island … where I experienced the joy of Christian loving friendship with an ALC pastor and his family.…

For too many reasons to list, I for one urge the Missouri Convention upcoming to approve altar and service fellowship with other Lutherans. Childish defenses of small plots of “reserved territory,” particularly insignificant in terms of salvation in Christ, are inexcusable and severely reprehensible.

McClellan AFB, Calif.

Briefly Speaking

Thanks to the new editor for the various changes occurring in CHRISTIANITY TODAY. I was especially pleased with the editorials in the November 8 issue. Their brevity and wide-ranging topics make for a fresh interest.… To be relevant and evangelical simultaneously calls for mental alertness and spiritual depth.

Minneapolis, Minn.

A Reforming Fire

I just finished reading the article by C. George Fry entitled, “The Reformation as an Evangelistic Movement” (Oct. 25) and it was refreshing. I agree with Dr. Fry when he says, “We could observe an Evangelism Festival on Reformation Day, to beseech God to give us a revived church in our century.” America needs an evangelistic church burning with the same kind of fire that inspired the Reformers.

Maple Park Lutheran Church

Lynnwood, Wash.

Gordon’S History

The editorial announcement about the acceptance by Dr. Harold John Ockenga of the presidency of Gordon College and Gordon Divinity School (Oct. 25) was inexact at certain points, and we feel rather strongly that some of these matters should be brought to the attention of your reading public.

It is not accurate to say that Gordon College came into being as a Baptist attempt to counteract the blight of Unitarianism. Our school came into existence as the Boston Missionary Training Institute. It arose out of a movement stimulated by the work of David Livingstone in Africa to send the Gospel to the Congo. Soon after its organization, it began to train interested students for Christian work in churches in the United States as well as for missionary work. The fact that the evangelical stance of Gordon has been a counterbalance to the effects of Unitarianism in New England is one for which we are grateful. It was not, however, the aim of the founders of the school to establish the college for this purpose.

Gordon has not been exclusively Baptist for almost sixty years. Indeed, there are those who maintain that it never was exclusively Baptist. In 1912, when the Clarendon Street Baptist Church where the school was housed burned, the neighboring United Presbyterian Church opened its doors to both the Clarendon Street Church and the Gordon Bible School. There were already at Gordon teachers who were not Baptist and many students who were not Baptist.…

I am afraid that it is not true also that Gordon is to be headed for the first time by a non-Baptist. The immediate past president of Gordon, Dr. James Forrester, is a minister in the United Presbyterian Church and a member of the Presbytery of Boston.

The election of Dr. Harold John Ockenga as the president of Gordon College and Gordon Divinity School has been hailed by its faculty members with warm enthusiasm, and we look forward to a period of eminent usefulness in Christian service.

Dean

Gordon Divinity School

Wenham, Mass.

• According to Who’s Who in America for 1968–69, Dr. Forrester was ordained to the Baptist ministry in 1942.—ED.

Justice For C.E.F.

Permit a protest against one small news item (Politics, Oct. 25). Citizens for Educational Freedom is not “a largely Catholic lobby”.… Are you aware that both the president and the board chairman of Citizens for Educational Freedom are non-Catholic, articulate Protestants who strongly support parentally controlled Christian schools?… To seek justice in an arena in which the Catholic is by and large the greatest collective victim is no more to be identified with a Catholic lobby than to seek justice in the racial arena identifies one as a Negro lobby.

The purpose of Citizens for Educational Freedom is not “seeking aid for private schools.” The goal is to seek justice and freedom for parents. CEF speaks out on educational aid issues since they affect the primary interest of freedom of religious choice. Most of us in CEF work against aid for schools—we work for fair-share aid for parents who cannot in conscience support the secularism of public education.

Trinity Chapel

Broomall, Pa.

Fan Mail For Wallace

This is a fan letter.… “The Clergy and George Wallace” by Wallace Henley (News, Oct. 25) … was an objective view and a very incisive story. As a former newspaper man, I have a great admiration for fellow members of the craft who do an exceptional job.

Opelika, Ala.

Please cancel my subscription immediately.… I have been increasingly disenchanted with CHRISTIANITY TODAY as you seem to be slipping more and more to the liberal side. The [report on George Wallace] was the final straw.

I am not a rabid supporter of George Wallace, but when a publication that is purportedly a Christian publication waits until the last issue before Election Day to take a nasty sideswipe at a presidential candidate so he will have no chance at rebuttal before your readers go to the polls, I wonder with how much “Christian love” the content of the publication is determined.…

I used to place my used copies of this publication in hospital waiting rooms, doctors’ and dentists’ offices, and other public places, but I’m going to destroy every copy I have on hand to prevent them from falling into the hands of some innocent reader who may be misled by the liberal slanted articles.

Glenside, Pa.

The article indicates a bigotry unbecoming to a Christian periodical. First there is the title. Is it correct? It is not written by the clergy; it has taken no poll from the clergy. True, it quotes from the clergy; but the title is inaccurate. Second there is the caricature of Wallace. Is it true? No, here again is a juvenile position of standing off to make fun of something or somebody. George Wallace lacks love, the article says. Is your ridicule indicative of love?

In times past your periodical has said that the evangelicals are hurting the cause of Christ by being picayune. Beware lest you do the same. I am hurt and disappointed in you. There will be no Christmas gifts of CHRISTIANITY TODAY from our house this year.…

Your clay feet are sticking out!

Las Cruces, N. M.

This was a narrow biased group to base such a headline on.… You quote from men, who many feel are natural and not spiritual—professional religionists.… If you are spiritual or have been born again, only God knows this, then you should quote from men who are spiritual.

I was not a Wallace man—but this article … impressed my mind to vote for Wallace for I feel Henley is a sorry religious news editor as most are.

Atlanta, Ga.

Your main objection to Mr. Wallace seems to be that he is a poor example as a Christian. I agree with this, but frankly I had never thought of either of the three main contenders as being a very good example of true Christianity. If they were, I think their platforms would contain some plans and promises to do something about alcohol, Sabbath desecration etc. These are all lost causes.

Centralia, Ill.

Thanks for the “fan” mail. My humility has been affected, though I’m not sure which way.

Religion Editor

The Birmingham News

Birmingham, Ala.

The earth has been called “the visited planet” because it is one place (and who can tell if there are others?) in which the God of the Universe chose to appear. We for whose sake he showed himself can still visit the geographical spot on our planet that was the divine “bull’s-eye.” Bethlehem—elected, we are told by the prophet Micah, for the birth of Jesus Christ centuries before the event—is still a little town, a cluster of stone houses on a hillside surrounded by olive groves and vineyards; but one no longer has to ride a donkey or walk, as Mary and Joseph did, to get there. I took a taxi from the Damascus Gate in Jerusalem.

My guidebook told me that Bethlehem was the birthplace of King David, but did not mention Jesus Christ. As we approached the town I noticed a long line of Israeli school children wearing blue-and-white hats and singing “Jerusalem of Gold.” They were waiting to get into Rachel’s Tomb, one of the Jewish holy places opened to them by the victory of the Six-Day War.

In Manger Square there were tour buses, taxis, Israeli police cars, small boys selling postcards, and small girls selling olivewood beads. Teen-age boys clamored to show me the Church of the Nativity, an enormous, fortress-like structure that dominated the square. I didn’t want to be shown, nor to be told what I was supposed to think about what I saw—not this time. I wanted to go down into the cave alone. I had done some reading and learned that the church was built during the reign of Constantine over “a certain cave near the village,” according to Justin Martyr. Origen said it was “well known even by those who were not Christians,” as the scene of any event in the life of a small town is known by all. Surely a cave that had been used as a stable by the local inn would have been long remembered if there a baby had been born whom shepherds, bearing an astounding piece of information, had come in from the fields to see.

St. Jerome did not question that this was the very place, but he expressed regret that the mud cradle had been replaced by a silver one and that the whole thing—by the fourth century!—was much too commercialized. “There is nothing to see in Bethlehem,” he wrote.

Since his day there has been plenty to see at times. The church gleamed with silver, gold, silks, jewels, and candelabra before it was destroyed by the Samaritans. It now has a “new” (as of 1764) altar screen and many elaborate lamps. On the day I was there, the funeral of an Arab soldier, killed during the June War but found months later, was in progress. Black-veiled women followed the coffin, weeping softly. The fragrance of flowers mingled with the dusty odors of ancient stone and votive lamps.

When the tour groups had gone, I went down the staircase into the dim grotto. There the place of the birth of Jesus was marked by a silver star inscribed, HIC DE VIRGINE MARIA JESUS CHRISTUS NATUS EST.

This star is said to have been one of the causes of the Crimean War. The Roman Catholics had placed it, the Greeks removed it, and the Turks made the Greeks restore it. Today there are clear lines drawn in the church showing which area belongs to the Romans, which to the Greeks and Armenians. Bitter opposition meets any encroachment by one group into the territory of another.

Perhaps the unbelieving tourist can shuffle through the grotto with the crowd and come up again into the sunshine unchanged, hurriedly checking off another place “done.” But the visitor who believes the Latin words Christus natus est (even if he cannot accept the word hic, “here”) cannot be the same. In spite of destruction and bittnerness and commercialization and religious disputing and modern war, the overwhelming truth remains: The thing happened. It happened here, in Bethlehem. “The Expression of God became a human being and lived among us. We saw His splendor.… There is a grace in our lives because of His love.”

This is why the star is there.—ELISABETH ELLIOT, Franconia, New Hampshire.