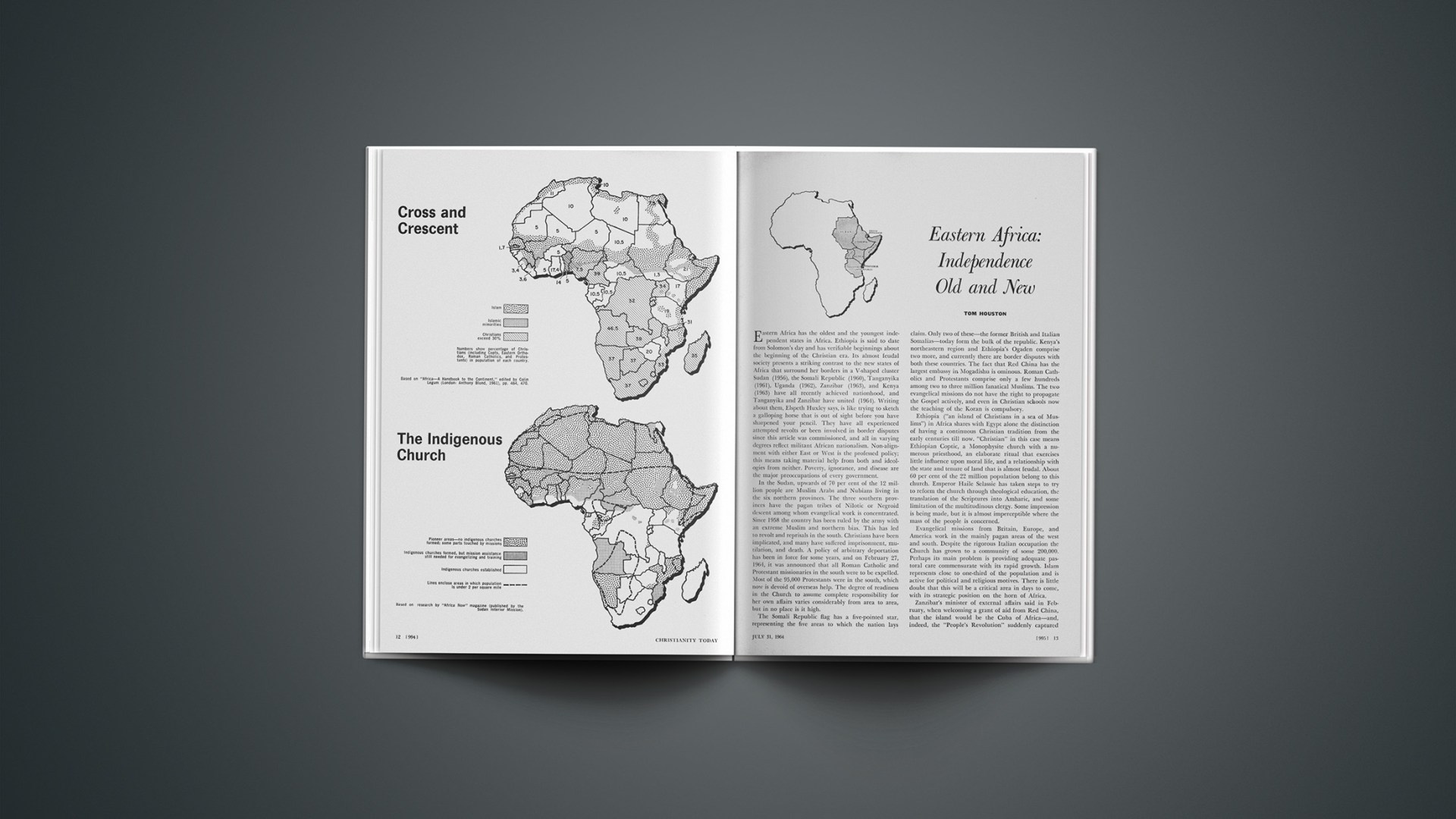

Eastern Africa has the oldest and the youngest independent states in Africa. Ethiopia is said to date from Solomon’s day and has verifiable beginnings about the beginning of the Christian era. Its almost feudal society presents a striking contrast to the new states of Africa that surround her borders in a V-shaped cluster Sudan (1956), the Somali Republic (1960), Tanganyika (1961), Uganda (1962), Zanzibar (1963), and Kenya (1963) have all recently achieved nationhood, and Tanganyika and Zanzibar have united (1964). Writing about them, Elspeth Huxley says, is like trying to sketch a galloping horse that is out of sight before you have sharpened your pencil. They have all experienced attempted revolts or been involved in border disputes since this article was commissioned, and all in varying degrees reflect militant African nationalism. Non-alignment with either East or West is the professed policy; this means taking material help from both and ideologies from neither. Poverty, ignorance, and disease are the major preoccupations of every government.

In the Sudan, upwards of 70 per cent of the 12 million people are Muslim Arabs and Nubians living in the six northern provinces. The three southern provinces have the pagan tribes of Nilotic or Negroid descent among whom evangelical work is concentrated. Since 1958 the country has been ruled by the army with an extreme Muslim and northern bias. This has led to revolt and reprisals in the south. Christians have been implicated, and many have suffered imprisonment, mutilation, and death. A policy of arbitrary deportation has been in force for some years, and on February 27, 1964, it was announced that all Roman Catholic and Protestant missionaries in the south were to be expelled. Most of the 95,000 Protestants were in the south, which now is devoid of overseas help. The degree of readiness in the Church to assume complete responsibility for her own affairs varies considerably from area to area, but in no place is it high.

The Somali Republic flag has a five-pointed star, representing the five areas to which the nation lays claim. Only two of these—the former British and Italian Somalias—today form the bulk of the republic. Kenya’s northeastern region and Ethiopia’s Ogaden comprise two more, and currently there are border disputes with both these countries. The fact that Red China has the largest embassy in Mogadishu is ominous. Roman Catholics and Protestants comprise only a few hundreds among two to three million fanatical Muslims. The two evangelical missions do not have the right to propagate the Gospel actively, and even in Christian schools now the teaching of the Koran is compulsory.

Ethiopia (“an island of Christians in a sea of Muslims”) in Africa shares with Egypt alone the distinction of having a continuous Christian tradition from the early centuries till now. “Christian” in this case means Ethiopian Coptic, a Monophysite church with a numerous priesthood, an elaborate ritual that exercises little influence upon moral life, and a relationship with the state and tenure of land that is almost feudal. About 60 per cent of the 22 million population belong to this church. Emperor Haile Selassie has taken steps to try to reform the church through theological education, the translation of the Scriptures into Amharic, and some limitation of the multitudinous clergy. Some impression is being made, but it is almost imperceptible where the mass of the people is concerned.

Evangelical missions from Britain, Europe, and America work in the mainly pagan areas of the west and south. Despite the rigorous Italian occupation the Church has grown to a community of some 200,000. Perhaps its main problem is providing adequate pastoral care commensurate with its rapid growth. Islam represents close to one-third of the population and is active for political and religious motives. There is little doubt that this will be a critical area in days to come, with its strategic position on the horn of Africa.

Zanzibar’s minister of external affairs said in February, when welcoming a grant of aid from Red China, that the island would be the Cuba of Africa—and, indeed, the “People’s Revolution” suddenly captured the headlines on January 12, 1964. This Muslim island off the coast of Tanganyika and now united with Tanganyika has been under Arab control for centuries, although Arabs are only 6 per cent of the 315,000 population. Only .1 percent are Christian, of the Roman or Anglo-Catholic tradition.

Surge Of Disaffection

Zanzibar’s revolution was quickly followed by a series of abortive army mutinies in Tanganyika, Uganda, and Kenya. This surge of disaffection came as a great shock to these young aspiring countries, underlining the mood of deep disillusionment that is creeping over sections of the population as they discover that independence is not bringing quickly enough all the benefits with which it has long been associated in the minds of the people. Despite herculean efforts by the governments, poverty, ignorance, and disease continue to dominate the lives of the majority. None of these lands is rich in natural resources; yet the stability of the political situation will greatly depend on economic progress.

The problems facing these three countries are largely the problems facing the Church. Their combined population of 26 million is increasing at the rate of 3 per cent annually. Sixty per cent of the population are under twenty-one years of age and 50 per cent under sixteen. In the past the Church has had a major share in education in each country, and it has educated most of the present leaders. Now the rapid expansion of educational facilities and the cessation of special privilege for Christianity in schools combine to challenge the Church to continue to influence school children by the sheer vitality of her own testimony. They present a tremendous call for youth work for which the Church is woefully unprepared, although determined beginnings are being made by most groups. After elementary education, youths flock to the towns to work or, more often, to swell the ranks of the unemployed, and they face the Church with a task in urban evangelism for which its previous rural character has given it no training.

There is danger that the educated classes might be lost to the Church; yet here again there are determined efforts to readjust to a problem that has sprung up almost overnight. Connected with this is the problem of an educated ministry. A recent survey estimated that there were some 6,000 students from all East Africa engaged in post-high-school studies of various kinds. In the four countries only six of these students were known to be preparing for the Protestant ministry. At the same time 600 were training for the Roman Catholic priesthood.

The small university colleges in five of these East African countries have a total student body of not more than 5,000, with perhaps an equal number in colleges overseas. There are evangelical student groups in each college, assisted by evangelicals on the faculty. The first area conference was held in March of this year.

The Roman Catholic membership in East Africa is about 16 per cent of the population, and the combined Protestant membership about 2 per cent. There is still considerable advance by the Roman Catholics, and they have a number of influential people in the leadership of these countries. Islam has its greatest strength in Tanganyika, with an estimated 27 per cent in 1953. In Uganda and Kenya the proportion is 5 per cent or less, and little significant Islamic advance has been reported since 1930. Christian work among Muslims is not extensive and has little success.

The picture of East Africa would be incomplete without reference to the immigrant races. The 380,000 Asians have a commercial influence out of all proportion to their numbers. There has been little impact with the Gospel here. The 90,000 Europeans, though decreasingly involved in administration, have still a significant part to play in development. The largest immigrant communities are in what was “settler” Kenya.

A Strong Tradition

The churches in East Africa have been blessed by having a strong evangelical tradition in every denomination, deriving from the early missionaries and from the widespread influence of the East African Revival in all the major denominations. This revival originated in Uganda in the 1930s in the Anglican church, which is still the only significant non-Roman body there. Revival fires are still burning in Uganda with a maturity and a scriptural foundation more pronounced than elsewhere in East Africa. The 800,000-strong Church of Uganda, pioneered by Hannington and Mackay, has also much nominalism, and there is to some extent a church within a church. This, though predominantly evangelical, is strongly ecumenical in its sympathies.

In Tanganyika, revival came later but profoundly influenced Lutherans, Mennonites, Anglicans, and Moravians, who form the greatest part of the 700,000-member Protestant community. Except for Anglo-Catholics at the coast, these churches and the interdenominational missions are predominantly evangelical. The denominational churches are involved in ecumenical discussions.

Kenya’s 822,000 Protestants present a somewhat different picture. The revival has only touched the denominational churches that have grown from British missionary activity, begun as far back as 1844. Yet there is an even larger number of Christians in the churches founded by evangelical missions (denominational and undenominational) from the United States and Canada that are unaffected by the revival; this is offset, however, by the cooperation among missionaries from all groups through the Christian Council of Kenya. So strong is evangelical anti-ecumenical feeling that the council has never been affiliated with the World Council of Churches.

The Church in East Africa has made a major contribution to the progress of these countries but has by political accident been identified with the colonial power. The position of privilege gone, the Church under its new African leadership is tackling with great dedication and vision the task of carrying forward in the name of its Lord the rapid expansion of the past.