In this series

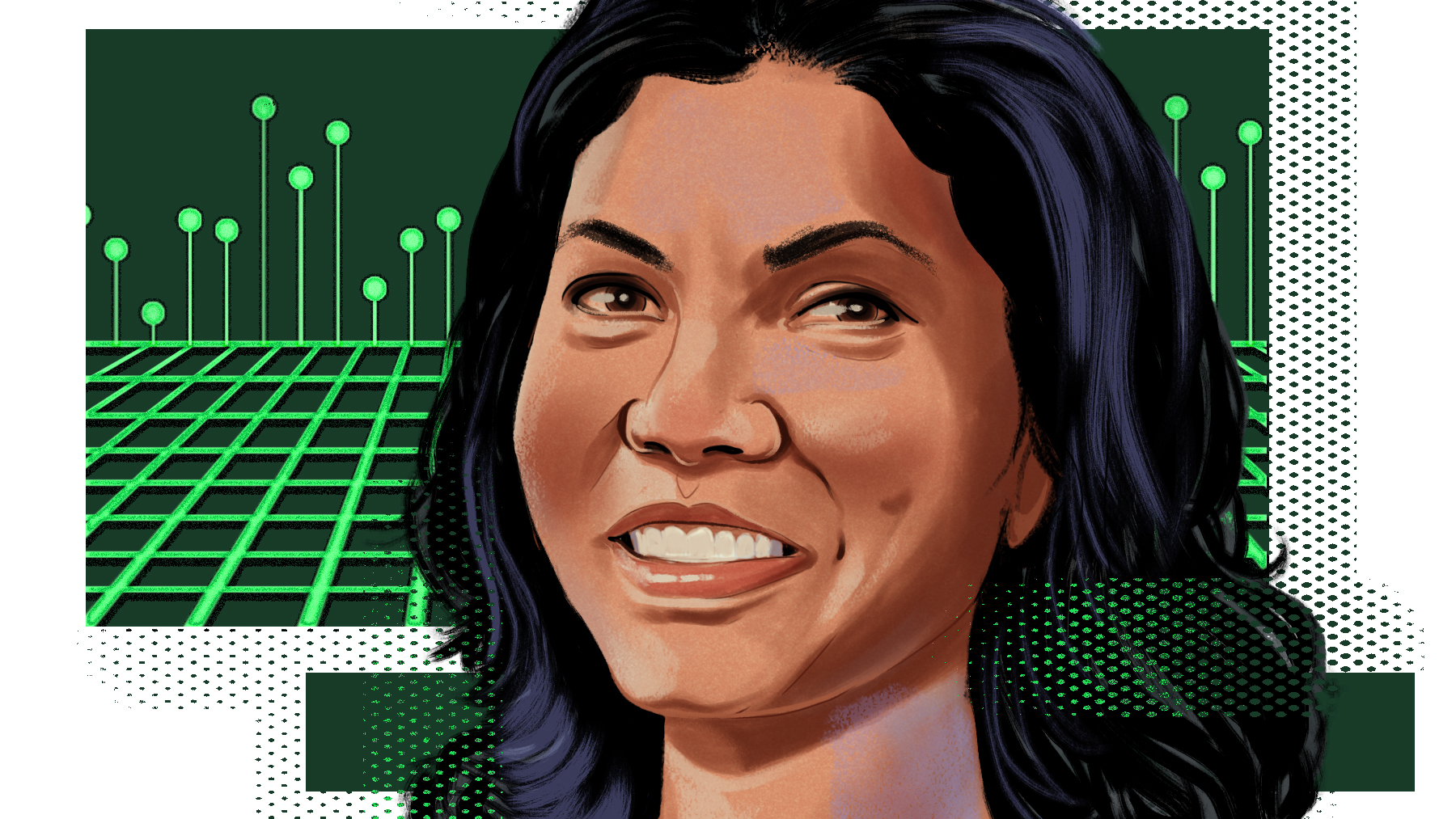

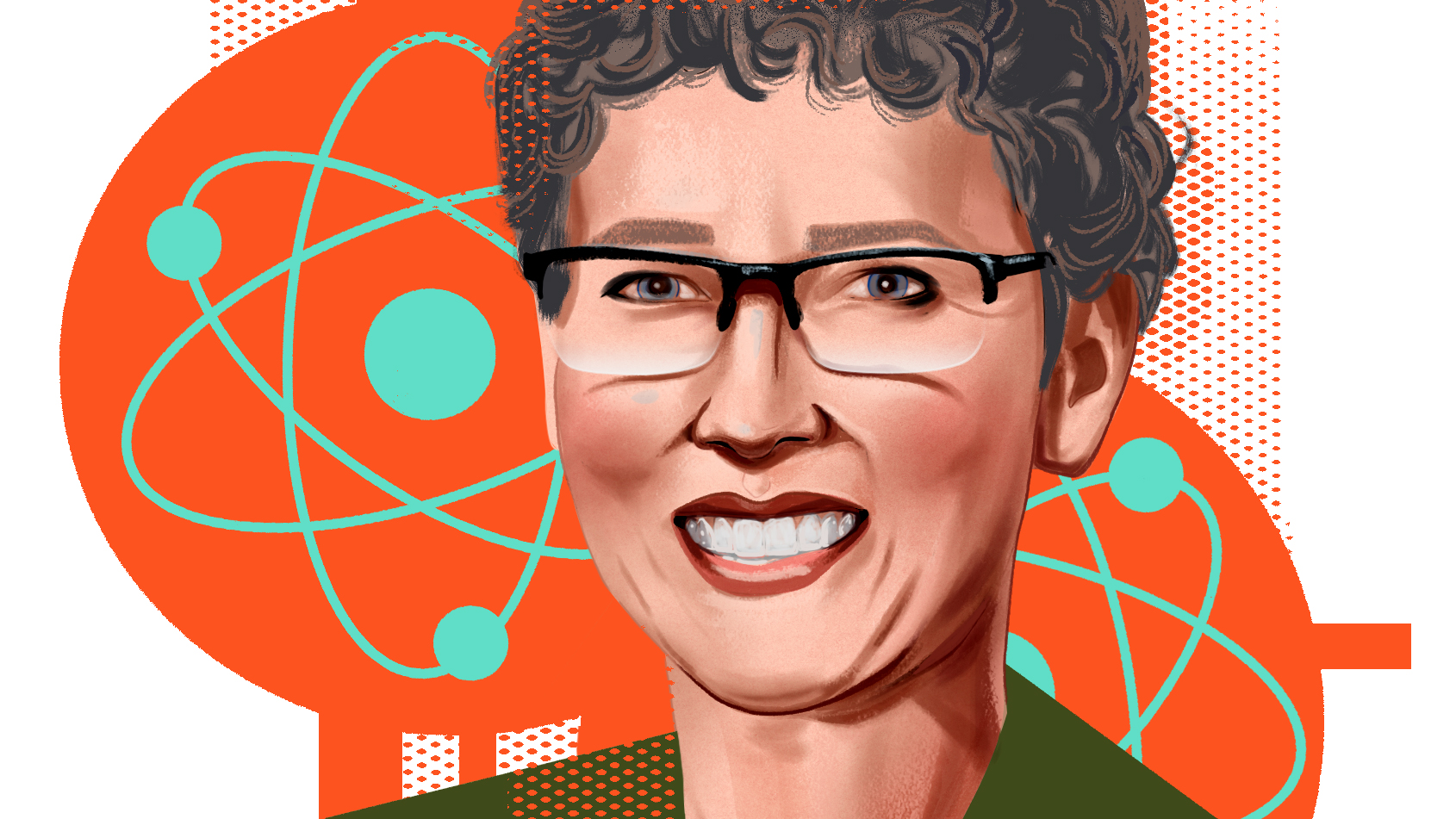

Computer scientist, Troy, New York

When Lydia Manikonda was accepted into a PhD program, her church community in rural India asked, “Why does a woman need to study that much instead of getting married and raising children?” Most of her friends were married at 18 or 20 years old. She was the only woman approaching 30 still in school and not married.

Her parents were split on whether this was the right path for her. Her mom “always told me and still tells me that women should stand on their own feet even though they are married, which was kind of a different message than I heard growing up in my ultraconservative church,” Manikonda said.

Jonathan Bartlett

Jonathan BartlettToday, she works with artificial intelligence and machine learning, using data-driven decision-making on social media platforms to understand people’s offline behavior, particularly related to mental health, obesity, or addictions.

She sees the technology field changing as women break barriers, while at the same time, computer scientists work to address biases in algorithms that harm underrepresented people. “I believe that this is just the beginning, but I am very excited to be in the world right now to experience and see how things are changing,” she said.

Manikonda is still riding the excitement of finishing her dissertation last spring. It wasn’t easy being the only female in the lab, she said. To create a support system, she reached out to other women in computer science and created a network of encouragement. She also finished as a new mom, though she entertained thoughts of quitting at times. Today, she is a tenure-track assistant professor at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in New York.