In the Bible, names matter. They aren’t mere ornaments or masks hiding deeper, private identities. According to Scripture, one’s name is one’s identity. To reveal one’s name is thus to manifest oneself. That’s why, when one’s life is so profoundly interrupted as to constitute an utterly new beginning—a revelation, an election, a conversion—one’s old name will no longer do. Abram becomes Abraham, Jacob becomes Israel, Simon becomes Peter, and Saul becomes Paul.

Few things are more important, therefore, than getting God’s Name right. (I’ll be capitalizing it from here on out.) I don’t know the last time you thought about the Name of God. But whether or not it entered your mind, it’s probably been in your prayers. That is, if you pray as Jesus taught us: “Our Father who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name” (Matt. 6:9, RSV throughout).

That God would consecrate his own Name is the first petition of the Lord’s Prayer. Not only, then, have you likely recently prayed about the Lord’s Name. The Name matters so much to Jesus that its sanctification precedes everything else we might ask of the Father.

Yet what is the Name of God? That’s the question.

God and Lord are candidates, as are other terms and titles in the Bible, from El Shaddai (Gen. 17:1) to King of heaven (Dan. 4:37). Years ago theologian Robert Jenson argued that Father, Son, and Holy Spirit (Matt. 28:19) is the personal Name of Israel’s God.

Beyond these, there is one moment in all of Scripture when God reveals his Name. At the burning bush, before the Exodus, the Lord declares his Name to Moses (Ex. 3). This is the Name by which Moses will announce exactly who sent him to Pharaoh, the Name by which the Israelites will know exactly who delivered them from slavery. Likewise, this is the Name that God declares to Moses after the Exodus, on Mount Sinai, when Moses asks God to show him his glory (33:17–34:9). God says this is his Name “for ever, and thus I am to be remembered throughout all generations” (3:15). And that Name is …

Well, what is it? How do you spell it? And how do you say it? Should you say it?

Scholars call the Name the Tetragrammaton because it consists of four consonants: יהוה in Hebrew; y-h-w-h in English. The revelation of the Name is easy to miss in translation, because in most versions the Name is rendered in small caps as “the Lord” (Ex. 3:15). God’s proclamation in the prior verse, “I am who I am” (v. 14), is a pun or riff on the Name’s connection to the Hebrew verb “to be.” The God of Israel is who he is: His sovereign freedom is unconditioned by anything in heaven or on earth. He alone is Creator, Redeemer, and Lord.

My hunch is that you, like me, have sometimes heard pastors, authors, and teachers pronounce aloud one or more Hebrew reconstructions of the Name. In American Protestantism, this has become something of a trend, even a fad. Preachers and scholars alike enunciate the Name with abandon. Nor is this habit limited to certain denominational subcultures or to traditions with a special emphasis on Israel, Judaism, and Zionism.

On the right, for example, Reformed theologian Peter Leithart has used the Name for decades. On the left, the same is true of the late Walter Brueggemann, an influential Old Testament scholar ordained in the United Church of Christ. Somewhere in the middle, you have a figure like John Mark Comer, who not only endorses writing and speaking the Name but also authored an entire book about it: God Has a Name: What You Believe About God Will Shape Who You Become (2017).

The motivations behind this renewal of attention to the divine Name are morally and theologically unimpeachable. Chief among these is a full-throated rejection of Marcionism, the heresy that the Old Testament is not inspired Scripture and that the Creator God of Israel is not the God and Father of Jesus Christ. Quite literally nothing is more important to handing on the gospel than repudiating this perennial falsehood. Gentile believers can be insecure in relation to Jewish heritage, and even when this insecurity avoids anti-Semitism, it perpetually drifts into pitting “the Old Testament God” against “the New Testament God.” This is a bit like comparing “the bride of my youth” to “the mother of my children.” They’re the same person.

The Lord of Hosts; the Almighty; the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob—this is one and the same as the God revealed in the Incarnation. Jesus isn’t deity in general incarnate. He is Israel’s God in flesh and blood. And as Comer rightly says, this God has a Name. He’s particular. He has a nature, a character, a personality. He’s not us multiplied. He’s not our best ideas projected onto eternity. He’s certainly not Zeus or Baal or any other idol. He is himself, the Lord God of Israel; besides him there is no other (Isa. 45:5).

So far, so good. Should we then go further and join the vogue for saying the Name? After all, if this is the Name by which God shall be known and remembered forever, shouldn’t we use it? What else is the Name—or any name—for? Israel’s Scriptures are both our authority and our paradigm for talking about God, and they use the Name constantly—indeed, thousands of times. Why wouldn’t we follow their lead? In our prayers and our sermons, should we not imitate Moses and David, Isaiah and Ezekiel?

I don’t think so. In fact, I’d like to make the case that the recent fashion of speaking God’s Name is a mistake. An understandable mistake, but a mistake nonetheless.

To be clear, there is no obvious permission or prohibition to be found in the Bible. This is one of those places where we cannot simply cite chapter and verse. We must instead exercise practical wisdom rooted in historical, scriptural, and theological judgment.

To begin, Christians should cease enunciating the Name out of respect for Jewish practice. Observant Jews do not speak the Name aloud. If they are reading the Bible and the Name is mentioned, they substitute Adonai, or “the Lord,” for it. English translations follow this practice. If, however, they want to be specific in their reference to the Name, whether in writing or in speech, Jews say HaShem, which literally means “the Name.”

It’s true that church practice cannot be settled by reference to the synagogue. Christianity and Judaism are divided over many things. Yet why add the Name to the list? Contemporary Jewish practice predates the writing of the New Testament. You may be sure that the Jews who wrote the New Testament were just as scrupulous in their reverence for the Name as Orthodox Jews are today. Nothing in the New Testament suggests an amendment to this reverence, and no one would suggest that the New Testament mandates pronouncing the Name.

Christian custom throughout history reflects this holy reticence. Given the agreement between the New Testament and patristic and medieval tradition, the burden of proof falls to those who would revise this long-standing discretion. If doing so erects unnecessary boundaries between Jews and Christians, offending the piety of men and women who descend from Abraham, love God, and seek to obey his commandments, why would we think this wise, loving, or necessary?

Second, there is a danger in Gentile fixation on Jewish language and history. This is the flip side of Marcionism. I’m thinking of the kind of Christian group that thinks it has found some secret level of faith in calling Jesus “Yeshua” or Peter “Simeon” or God “El.” The besetting temptation is to act as if the untranslated words contain a sort of magic. Hence, if we call Jesus “Yeshua,” then we are somehow closer to the “real” gospel or to the early church as it “actually” was.

Lest I be misunderstood, I’m not knocking attention or sensitivity to the details of Scripture. Every jot and tittle are significant. Nor do I have in mind Jewish believers in Jesus who quite rightly want to make explicit Jesus’ Jewishness, his messianic identity, and the names and titles that belong to him. Rather, I’m thinking of Gentile Christians who see Gentile faith in Abraham’s God as somehow second-rate and therefore in need of sprucing up with transliterated Hebrew. We can sympathize with the impulse without sanctioning the practice.

Third, given the common preoccupation with speaking the Name, there is a deep irony for those who insist on it: The truth is that we do not know its pronunciation. The current favorite is a reasonable historical reconstruction, just as previous generations did their best. Yet for those who believe that using Hebrew words will bring greater spiritual insight or authenticity, a best guess isn’t going to cut it.

I have already alluded to the fourth reason why Christians should not speak God’s Name. Put plainly, this is the example set for us by Jesus and the apostles in the New Testament. Kendall Soulen, a professor of theology at Emory University, makes a powerful version of this argument in his recent book, Irrevocable: The Name of God and the Unity of the Christian Bible. Soulen draws attention to the fact that mention of God’s Name does not cease between the Testaments. On the contrary, the authors of the New Testament are positively enamored with it. They refer to it over and over again. Yet they do so in properly pious fashion: by not saying it.

At this point, one might make either of two objections. On one hand, the New Testament is written in Greek and quotes from the Septuagint, a Greek translation of the Old Testament. What of the Galilean Jesus and his disciples’ Aramaic speech? On the other hand, even bracketing translation, the practice of nonpronunciation reflects Jewish custom at the time. Even if Jesus did not speak the Name, perhaps this was for cultural rather than theological reasons.

In my view, this objection gives Jesus far too little credit. Had he wanted his followers to change this practice, he would have said so—and his apostles would have reported this to us. When Jesus merely alludes to the Name, as when he says, “Before Abraham was, I am,” he has to hide himself lest he be stoned to death (John 8:58–59). Just as the Lord’s Name can be transliterated into English, the same can be done into Greek. The issue has not been lost in translation.

Furthermore, it would be inaccurate to say that Jesus and the apostles merely observe a local convention, passively avoiding what might cause offense to the simple and unenlightened. They revel in the unspoken Name. This is evident in the extraordinary variety of euphemisms they deploy that refer to the Name without ever pronouncing it.

Once you see this in the New Testament, you’ll never be able to unsee it. Part of the reason you may not have noticed it before is its sheer ubiquity in the texts. Who, according to the apostles, is God? Answer: He is “Power” (Mark 14:62); he is “the Blessed” (v. 61); the one “who sits upon the throne” (Rev. 5:13), “who was and is and is to come” (4:8). He is “the Most High” (Acts 7:48), “Alpha and the Omega” (Rev. 1:8), “the Almighty” (Rev. 1:8), the “faithful Creator” (1 Pet. 4:19), the “Savior” (1 Tim. 2:3), and the “Majesty in heaven” (Heb. 8:1). He is—as the New Testament consistently quotes from the Septuagint—the Lord.

This practice is not theologically neutral. It teaches us about the nature of Jesus’ divinity. Jesus is Lord. That is the bedrock confession of faith in Christ (Rom. 10:9). Jesus isn’t a lord like Caesar. Jesus is Lord like God. Why? Because Jesus is God like God. He is, in the words of the Nicene Creed, “God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God.” Jesus is the Lord, the holy Name in human form.

In other words, for the apostles, Lord is more than a title. It is the very Name of God, even as it is also the Name of Jesus. He didn’t receive it at a given point in time. The Name belongs to him by nature. From all eternity, Jesus is the Lord. In him the Name “became flesh and dwelt among us” (John 1:14).

If Jesus is the Name, because the Name is his from everlasting to everlasting, then we should look to him to learn how we ought to address God. This is the fifth and final reason for principled nonpronunciation of the Name revealed to Moses. For, thankfully, we do not have to speculate about how we should speak to God. Jesus was quite explicit about it. His disciples asked him how to pray (Luke 11:1), and he told them. I quoted his answer above. Like Jesus, we should address God with these words (Matt. 6:9):

“Our Father.”

This address, to be sure, is not a replacement for the Name. Nor is it unique in the same way, for it is taken from the human family. (Though I should add that Paul claims the order is reversed; according to Ephesians 3:15, all earthly paternity takes its name from the heavenly Father.) Nevertheless, “Father” is how Jesus himself addressed God, and his command—both an imperative and an invitation—was for us to do the same.

It is difficult to overstate the significance of this summons. God is not our Father by nature. Whether as creatures or as sinners, we have no right to call him Father. To call God our Father is a gift. It is Jesus extending his own unique relationship with God to us, including us in his sonship so that we, too, might be children of God.

Paul recognizes the shocking grace of this act. Because “every one who calls upon the name of the Lord will be saved” (Rom. 10:13; Joel 2:32), when we are baptized in the triune Name, God the Father sends “the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, crying, ‘Abba! Father!’” (Gal. 4:6). The Holy Spirit is the Spirit of sonship, of adoption (Rom. 8:15), so that all who put their faith in God’s Name might become his sons and daughters—“born, not of blood nor of the will of the flesh nor of the will of man, but of God” (John 1:13).

On the eve of his crucifixion, before his arrest, Jesus prayed. Listening to his prayer, we become eavesdroppers on a mystery: the human petitions of God the Son to God the Father, offered in the power of God the Spirit. The High Priest of Israel is here interceding for God’s people before the throne. Over and over, he begs blessing and protection for his followers. Over and over, he addresses God as Father. And over and over, he speaks of the Name:

I have manifested thy name to the men whom thou gavest me out of the world; thine they were, and thou gavest them to me, and they have kept thy word. …

Holy Father, keep them in thy name, which thou hast given me, that they may be one, even as we are one. While I was with them, I kept them in thy name, which thou hast given me. …

I made known to them thy name, and I will make it known, that the love with which thou hast loved me may be in them, and I in them. (John 17:6, 11–12, 26)

Jesus has made known God’s Name to all who put their faith in him. He has kept us in the Name, for if we are God’s children, his Name is upon us. We are marked by it. We honor and revere it. We ask God to sanctify it. With Jesus in Jerusalem, we pray, “Father, glorify thy name.” And with Jesus, we hear the reply from heaven: “I have glorified it, and I will glorify it again” (John 12:28).

We do all this, however, not by pronouncing the Name but—to shift just two words around—by not pronouncing the Name. We certainly will not honor the Name through constant, casual chatter, slinging it around with a shrug. With regard to the Name, we believers ought to be like the Book of Esther, in which mention of God’s presence is all the more notable for its surprising and conspicuous absence. You will have noticed by now that this article is Esther-like in just this respect. The purpose is not to be coy. I am trying to practice what I preach, even in print.

In short, the church marks the holiness of the Lord’s Name through unswerving, unyielding, and reverent silence. By refusing to speak it aloud, we simultaneously indicate and participate in God’s work to set his Name apart from every other name in heaven or on earth. And by addressing God as Jesus showed us to do, we welcome others to do the same.

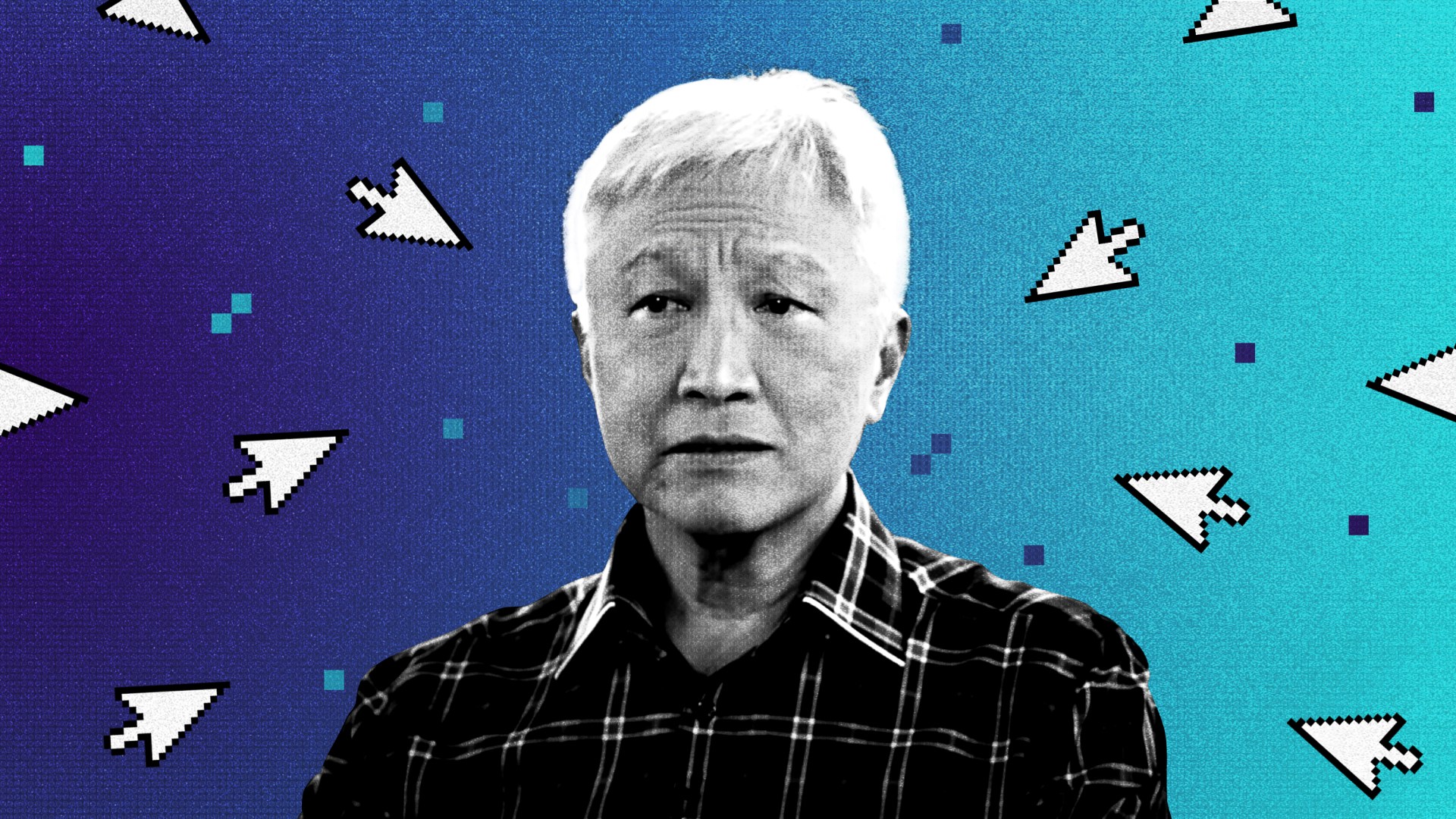

Brad East is an associate professor of theology at Abilene Christian University. He is the author of four books, including The Church: A Guide to the People of God and Letters to a Future Saint.