This spring, the Trump administration is reportedly entertaining a “chorus of ideas … for persuading Americans to get married and have more children.”

Some of the proposals are straightforward: cash payments for new moms and a more generous child tax credit. Others are slantwise: earmarked Fulbright scholarships, menstrual cycle education, endometriosis research, and loosened car seat laws.

And then there’s the National Medal of Motherhood, to be bestowed upon women with more than six children.

That idea came via a draft executive order from Simone and Malcolm Collins, two of the most provocative figures in an informal pronatalist coalition of conservative, religious, family-values types and catastrophist techno-utopians. Members of the latter group, the Collinses believe that declining birth rates will prove apocalyptic and that having children is a civilization-saving imperative.

Simone, now gearing up for her fifth birth, isn’t yet eligible for her proposed medal. But she hopes to have at least three more children, ideally as many as ten. She hones her body for IVF-facilitated pregnancies staggered an even nine months apart, walking on a standing-desk treadmill and eating no-sugar yogurt. Her repeated C-sections are medically risky. But she would be “happy to die in labor,” she says, for the cause of more kids.

Not just any kids, though. The Collinses select embryos optimized for high IQ scores and future health, consenting to have only the children they believe will be genetically superior. Embryos with high risk factors for cancer or schizophrenia, Alzheimer’s or depression or anxiety will not be chosen. This isn’t eugenics, they insist, but polygenics—not ableist engineering but innocuous parental choice.

It’s good that the Collinses, given the size of their platform, are explicitly antieugenics. But, to put it mildly, “polygenics” also gives me the ick. Even assuming good intentions, selecting for eye color or math skills or a sense of humor is a slippery slope at best, a sheer cliff at worst. It would be easy to fall off the edge, to crash away from the Christian conception of human dignity—bestowed merely by dint of being made in God’s image, which very much includes people with low IQs and cancer diagnoses.

The National Medal of Motherhood gives me the ick for related reasons. It’s true that present-day plunging birthrates are a legitimately novel situation in human history. My toddler son may live to see the global population peak and begin a steep downhill slide.

But though guilt by similarity is unfair, I can’t help but notice that such honorifics have been awarded before, by the Nazis and the Soviets and other authoritarian regimes. The medal idea isn’t a novel solution to our novel problem. The undertone (really, the overtone) has been Do your civic duty, ladies, and birth the right kind of citizens.

Historical precedent aside, I’ll again assume good intentions (more difficult given some of the white nationalist bedfellows who attend gatherings like NatCon—but I digress). What’s so bad about honoring mothers? I can imagine medal proponents protesting. It’s Mother’s Day! What’s wrong with breakfast in bed, a bouquet of flowers, a nice gold medal for the woman who raised you—especially seven of you?

In a word: nothing. I have only one kid, but I hope he scribbles a card and gives it to me this Sunday. A medal, though? From the government? It strikes me as an exercise in missing the point.

I’ve been following the pronatalists with interest in the months since I became a mother; these days, I’m feeling very pro-child, mine and everyone else’s. The pronatalist label has baggage (see the aforementioned ick, the Elon Musk “breeding spree,” and goofy ideas like parents getting more votes in elections). But I’m entirely on board with the “pretty unobjectionable” premise, as Elizabeth Bruenig puts it, that “having children is good and ought to be supported by society.”

Reasonable promotion might include cash subsidies or new car seat laws or more infertility research. But at the very least it requires a shift in how we talk and think about mothers: not as martyrs “in hell” but also not as national heroes bedecked with ribbons.

It seems as if these two cultural caricatures are diametrically opposed. One side has “childless cat ladies” and vacationing DINKs. It has the harried moms of hell themselves, bedraggled and lonely and depleted. On the other: the tradwives, churning butter while wearing lipstick, benevolent and beloved queens of their homes. Also Simone Collins, doing her duty at risk of death.

But really, these caricatures aren’t as different as they seem. They share the same idea of motherhood as not just sacrifice but self-abnegation, not just difficult but so horrific as to deserve either condescending pity or simpering praise. One side sees moms as less than human, in danger of “losing themselves.” Another sees moms as more than human, heroes to be put on a pedestal. Both are, well, dehumanizing.

For me—and, I think, for most mothers—neither pity nor pedestals do motherhood justice.

Cringe as it may be to admit, being a mom is a blessing. Often, taking care of my toddler makes me happy. We blow bubbles and eat sandwiches. This week, he learned the word star. But when caregiving is not happy, when I am cradling and rocking and administering medicine, well, there’s joy there, in the rocking chairs and emergency rooms. Calling tantrums and teething “joy” can sound like public relations for parenting. What can I say? I have found motherhood a liberation even in its limitations. In losing myself, I’ve found myself. This is not a pitiable condition.

I shouldn’t be so surprised. We must lose our lives for Christ to keep them (Matt. 16:24–25). It’s more blessed to give than to receive (Acts 20:35). Being “poured out” is not at odds with being filled up (Phil. 2:17–18).

But having a baby does not a saint make. Motherhood can create the conditions for sanctification, yet it is certainly not sufficient. I’m in some ways more inclined to sin as a parent: I’m newly insular (safety for my baby!) and greedy (money for my baby!). Contrary to what horror stories from pews and airplanes suggest, being a mom still comes with status, praise from old folks in the grocery store and doting aunties at church. That attention makes me prideful and self-satisfied. Imagine if there were a medal thrown in.

Respectability, it turns out, is not a Christian virtue. The prize we’re running for is not civic duty or familial bliss, though we may get those thrown in. It’s the “upward call of God in Christ Jesus,” accessible to all (Phil. 3:14, ESV).

Might that simple truth take some pressure off our conversations about parenthood? Might it even be pronatalist in its realism and faithfulness, understanding children and the women who birth them as neither tools nor burdens? Motherhood needn’t subsume a woman—for better or for worse. Children are a “heritage from the Lord,” not a project to be optimized or imposed (Ps. 127:3).

Christians are called to care for the vulnerable—which looks more like meal trains for new moms than public accolades. This Mother’s Day, my church won’t do much to mark the holiday, and I think that’s for the best. I know of fellow congregants whose mothers have died, whose mothers abused them, who want children but don’t have them. If caring for them, as they’ve cared for me, means forgoing my from-the-pulpit kudos and flowers, that seems like a small price to pay.

I don’t need commendation from the church or the state. From my child? That’s another story. See the fifth commandment. See Proverbs. To my son—to my husband—take note. I wouldn’t mind breakfast in bed.

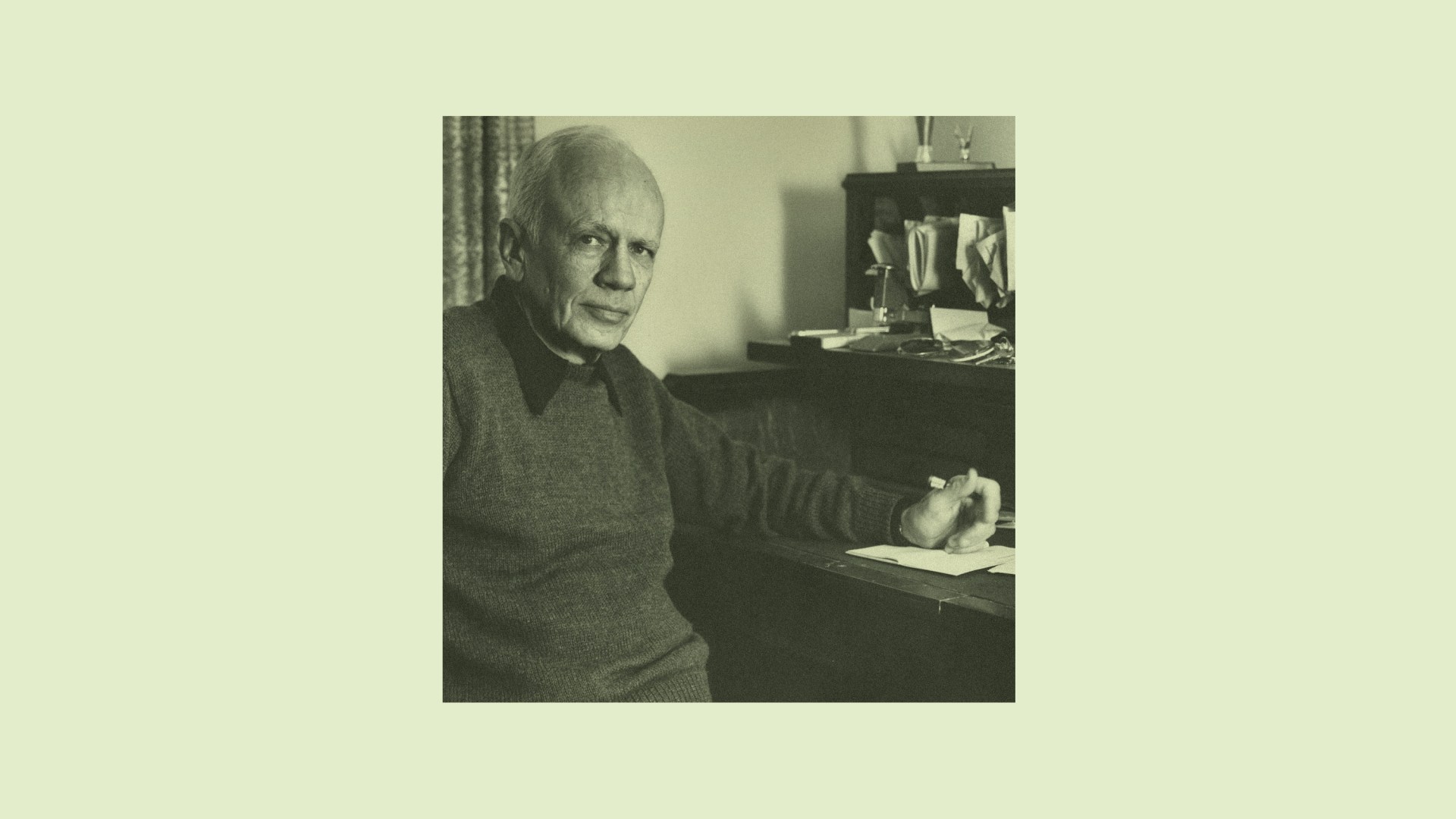

Kate Lucky is the senior editor of culture and engagement at Christianity Today.