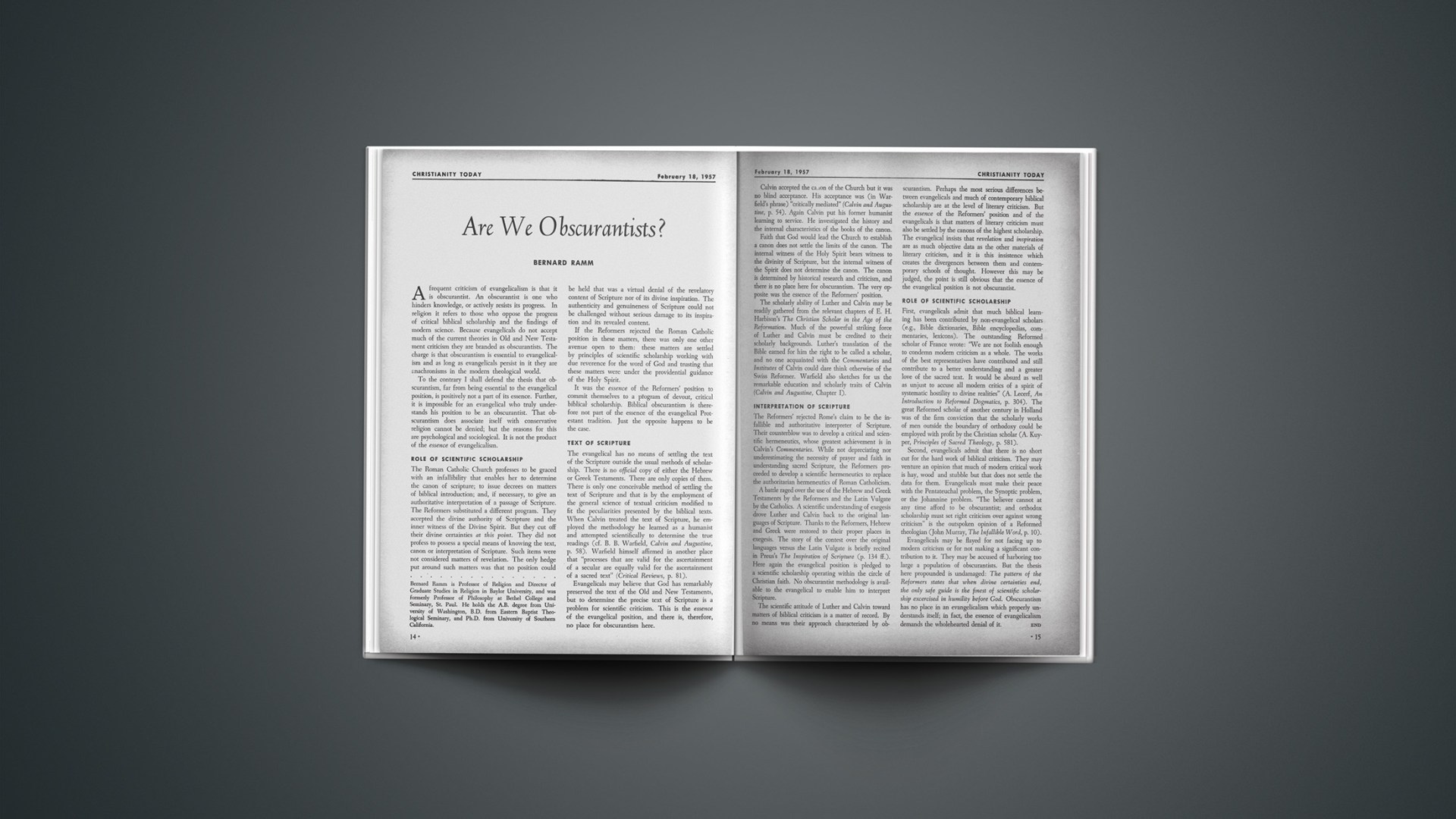

A frequent criticism of evangelicalism is that it is obscurantist. An obscurantist is one who binders knowledge, or actively resists its progress. In religion it refers to those who oppose the progress of critical biblical scholarship and the findings of modern science. Because evangelicals do not accept much of the current theories in Old and New Testament criticism they are branded as obscurantists. The charge is that obscurantism is essential to evangelicalism and as long as evangelicals persist in it they are anachronisms in the modern theological world.

To the contrary I shall defend the thesis that obscurantism, far from being essential to the evangelical position, is positively not a part of its essence. Further, it is impossible for an evangelical who truly understands his position to be an obscurantist. That obscurantism does associate itself with conservative religion cannot be denied; but the reasons for this are psychological and sociological. It is not the product of the essence of evangelicalism.

Role Of Scientific Scholarship

The Roman Catholic Church professes to be graced with an infallibility that enables her to determine the canon of scripture; to issue decrees on matters of biblical introduction; and, if necessary, to give an authoritative interpretation of a passage of Scripture. The Reformers substituted a different program. They accepted the divine authority of Scripture and the inner witness of the Divine Spirit. But they cut off their divine certainties at this point. They did not profess to possess a special means of knowing the text, canon or interpretation of Scripture. Such items were not considered matters of revelation. The only hedge put around such matters was that no position could be held that was a virtual denial of the revelatory content of Scripture nor of its divine inspiration. The authenticity and genuineness of Scripture could not be challenged without serious damage to its inspiration and its revealed content.

If the Reformers rejected the Roman Catholic position in these matters, there was only one other avenue open to them: these matters are settled by principles of scientific scholarship working with due reverence for the word of God and trusting that these matters were under the providential guidance of the Holy Spirit.

It was the essence of the Reformers’ position to commit themselves to a program of devout, critical biblical scholarship. Biblical obscurantism is therefore not part of the essence of the evangelical Protestant tradition. Just the opposite happens to be the case.

Text Of Scripture

The evangelical has no means of settling the text of the Scripture outside the usual methods of scholarship. There is no official copy of either the Hebrew or Greek Testaments. There are only copies of them. There is only one conceivable method of settling the text of Scripture and that is by the employment of the general science of textual criticism modified to fit the peculiarities presented by the biblical texts. When Calvin treated the text of Scripture, he employed the methodology he learned as a humanist and attempted scientifically to determine the true readings (cf. B. B. Warfield, Calvin and Augustine, p. 58). Warfield himself affirmed in another place that “processes that are valid for the ascertainment of a secular are equally valid for the ascertainment of a sacred text” (Critical Reviews, p. 81).

Evangelicals may believe that God has remarkably preserved the text of the Old and New Testaments, but to determine the precise text of Scripture is a problem for scientific criticism. This is the essence of the evangelical position, and there is, therefore, no place for obscurantism here.

Calvin accepted the canon of the Church but it was no blind acceptance. His acceptance was (in Warfield’s phrase) “critically mediated” (Calvin and Augustine, p. 54). Again Calvin put his former humanist learning to service. He investigated the history and the internal characteristics of the books of the canon.

Faith that God would lead the Church to establish a canon does not settle the limits of the canon. The internal witness of the Holy Spirit bears witness to the divinity of Scripture, but the internal witness of the Spirit does not determine the canon. The canon is determined by historical research and criticism, and there is no place here for obscurantism. The very opposite was the essence of the Reformers’ position.

The scholarly ability of Luther and Calvin may be readily gathered from the relevant chapters of E. H. Harbison’s The Christian Scholar in the Age of the Reformation. Much of the powerful striking force of Luther and Calvin must be credited to their scholarly backgrounds. Luther’s translation of the Bible earned for him the right to be called a scholar, and no one acquainted with the Commentaries and Institutes of Calvin could dare think otherwise of the Swiss Reformer. Warfield also sketches for us the remarkable education and scholarly traits of Calvin (Calvin and Augustine, Chapter I).

Interpretation Of Scripture

The Reformers’ rejected Rome’s claim to be the infallible and authoritative interpreter of Scripture. Their counterblow was to develop a critical and scientific hermeneutics, whose greatest achievement is in Calvin’s Commentaries. While not depreciating nor underestimating the necessity of prayer and faith in understanding sacred Scripture, the Reformers proceeded to develop a scientific hermeneutics to replace the authoritarian hermeneutics of Roman Catholicism.

A battle raged over the use of the Hebrew and Greek Testaments by the Reformers and the Latin Vulgate by the Catholics. A scientific understanding of exegesis drove Luther and Calvin back to the original languages of Scripture. Thanks to the Reformers, Hebrew and Greek were restored to their proper places in exegesis. The story of the contest over the original languages versus the Latin Vulgate is briefly recited in Preus’s The Inspiration of Scripture (p. 134 ff.). Here again the evangelical position is pledged to a scientific scholarship operating within the circle of Christian faith. No obscurantist methodology is available to the evangelical to enable him to interpret Scripture.

The scientific attitude of Luther and Calvin toward matters of biblical criticism is a matter of record. By no means was their approach characterized by obscurantism. Perhaps the most serious differences between evangelicals and much of contemporary biblical scholarship are at the level of literary criticism. But the essence of the Reformers’ position and of the evangelicals is that matters of literary criticism must also be settled by the canons of the highest scholarship. The evangelical insists that revelation and inspiration are as much objective data as the other materials of literary criticism, and it is this insistence which creates the divergences between them and contemporary schools of thought. However this may be judged, the point is still obvious that the essence of the evangelical position is not obscurantist.

Role Of Scientific Scholarship

First, evangelicals admit that much biblical learning has been contributed by non-evangelical scholars (e.g., Bible dictionaries, Bible encyclopedias, commentaries, lexicons). The outstanding Reformed scholar of France wrote: “We are not foolish enough to condemn modern criticism as a whole. The works of the best representatives have contributed and still contribute to a better understanding and a greater love of the sacred text. It would be absurd as well as unjust to accuse all modern critics of a spirit of systematic hostility to divine realities” (A. Lecerf, An Introduction to Reformed Dogmatics, p. 304). The great Reformed scholar of another century in Holland was of the firm conviction that the scholarly works of men outside the boundary of orthodoxy could be employed with profit by the Christian scholar (A. Kuyper, Principles of Sacred Theology, p. 581).

Second, evangelicals admit that there is no short cut for the hard work of biblical criticism. They may venture an opinion that much of modern critical work is hay, wood and stubble but that does not settle the data for them. Evangelicals must make their peace with the Pentateuchal problem, the Synoptic problem, or the Johannine problem. “The believer cannot at any time afford to be obscurantist; and orthodox scholarship must set right criticism over against wrong criticism” is the outspoken opinion of a Reformed theologian (John Murray, The Infallible Word, p. 10).

Evangelicals may be flayed for not facing up to modern criticism or for not making a significant contribution to it. They may be accused of harboring too large a population of obscurantists. But the thesis here propounded is undamaged: The pattern of the Reformers states that when divine certainties end, the only safe guide is the finest of scientific scholarship excercised in humility before God. Obscurantism has no place in an evangelicalism which properly understands itself; in fact, the essence of evangelicalism demands the wholehearted denial of it.

Bernard Ramm is Professor of Religion and Director of Graduate Studies in Religion in Baylor University, and was formerly Professor of Philosophy at Bethel College and Seminary, St. Paul. He holds the A.B. degree from University of Washington, B.D. from Eastern Baptist Theological Seminary, and Ph.D. from University of Southern California.