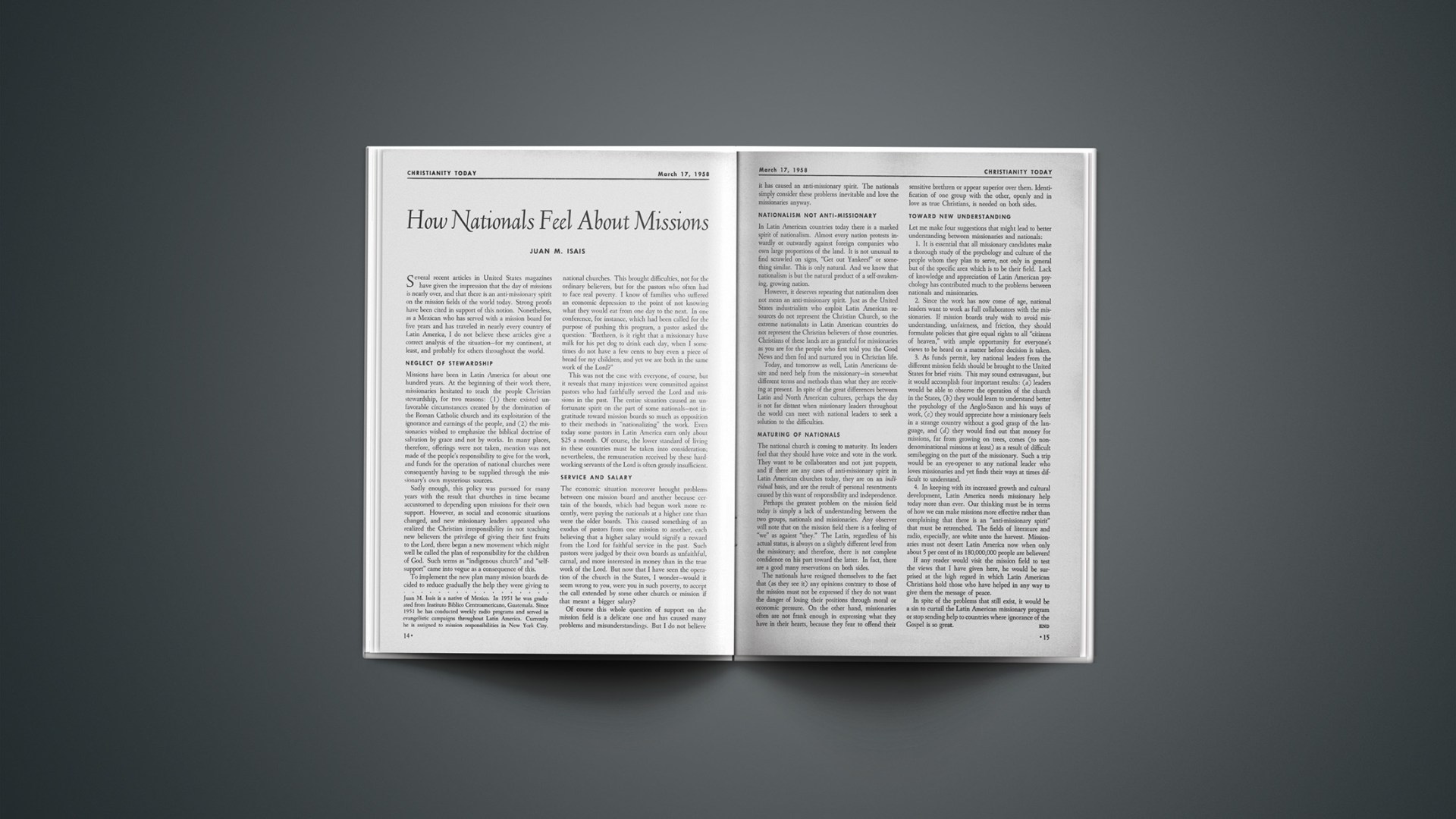

Several recent articles in United States magazines have given the impression that the day of missions is nearly over, and that there is an anti-missionary spirit on the mission fields of the world today. Strong proofs have been cited in support of this notion. Nonetheless, as a Mexican who has served with a mission board for five years and has traveled in nearly every country of Latin America, I do not believe these articles give a correct analysis of the situation—for my continent, at least, and probably for others throughout the world.

Neglect Of Stewardship

Missions have been in Latin America for about one hundred years. At the beginning of their work there, missionaries hesitated to teach the people Christian stewardship, for two reasons: (1) there existed unfavorable circumstances created by the domination of the Roman Catholic church and its exploitation of the ignorance and earnings of the people, and (2) the missionaries wished to emphasize the biblical doctrine of salvation by grace and not by works. In many places, therefore, offerings were not taken, mention was not made of the people’s responsibility to give for the work, and funds for the operation of national churches were consequently having to be supplied through the missionary’s own mysterious sources.

Sadly enough, this policy was pursued for many years with the result that churches in time became accustomed to depending upon missions for their own support. However, as social and economic situations changed, and new missionary leaders appeared who realized the Christian irresponsibility in not teaching new believers the privilege of giving their first fruits to the Lord, there began a new movement which might well be called the plan of responsibility for the children of God. Such terms as “indigenous church” and “self-support” came into vogue as a consequence of this.

To implement the new plan many mission boards decided to reduce gradually the help they were giving to national churches. This brought difficulties, not for the ordinary believers, but for the pastors who often had to face real poverty. I know of families who suffered an economic depression to the point of not knowing what they would eat from one day to the next. In one conference, for instance, which had been called for the purpose of pushing this program, a pastor asked the question: “Brethren, is it right that a missionary have milk for his pet dog to drink each day, when I sometimes do not have a few cents to buy even a piece of bread for my children; and yet we are both in the same work of the Lord?”

This was not the case with everyone, of course, but it reveals that many injustices were committed against pastors who had faithfully served the Lord and missions in the past. The entire situation caused an unfortunate spirit on the part of some nationals—not ingratitude toward mission boards so much as opposition to their methods in “nationalizing” the work. Even today some pastors in Latin America earn only about $25 a month. Of course, the lower standard of living in these countries must be taken into consideration; nevertheless, the remuneration received by these hard-working servants of the Lord is often grossly insufficient.

Service And Salary

The economic situation moreover brought problems between one mission board and another because certain of the boards, which had begun work more recently, were paying the nationals at a higher rate than were the older boards. This caused something of an exodus of pastors from one mission to another, each believing that a higher salary would signify a reward from the Lord for faithful service in the past. Such pastors were judged by their own boards as unfaithful, carnal, and more interested in money than in the true work of the Lord. But now that I have seen the operation of the church in the States, I wonder—would it seem wrong to you, were you in such poverty, to accept the call extended by some other church or mission if that meant a bigger salary?

Of course this whole question of support on the mission field is a delicate one and has caused many problems and misunderstandings. But I do not believe it has caused an anti-missionary spirit. The nationals simply consider these problems inevitable and love the missionaries anyway.

Nationalism Not Anti-Missionary

In Latin American countries today there is a marked spirit of nationalism. Almost every nation protests inwardly or outwardly against foreign companies who own large proportions of the land. It is not unusual to find scrawled on signs, “Get out Yankees!” or something similar. This is only natural. And we know that nationalism is but the natural product of a self-awakening, growing nation.

However, it deserves repeating that nationalism does not mean an anti-missionary spirit. Just as the United States industrialists who exploit Latin American resources do not represent the Christian Church, so the extreme nationalists in Latin American countries do not represent the Christian believers of those countries. Christians of these lands are as grateful for missionaries as you are for the people who first told you the Good News and then fed and nurtured you in Christian life.

Today, and tomorrow as well, Latin Americans desire and need help from the missionary—in somewhat different terms and methods than what they are receiving at present. In spite of the great differences between Latin and North American cultures, perhaps the day is not far distant when missionary leaders throughout the world can meet with national leaders to seek a solution to the difficulties.

Maturing Of Nationals

The national church is coming to maturity. Its leaders feel that they should have voice and vote in the work. They want to be collaborators and not just puppets, and if there are any cases of anti-missionary spirit in Latin American churches today, they are on an individual basis, and are the result of personal resentments caused by this want of responsibility and independence.

Perhaps the greatest problem on the mission field today is simply a lack of understanding between the two groups, nationals and missionaries. Any observer will note that on the mission field there is a feeling of “we” as against “they.” The Latin, regardless of his actual status, is always on a slightly different level from the missionary; and therefore, there is not complete confidence on his part toward the latter. In fact, there are a good many reservations on both sides.

The nationals have resigned themselves to the fact that (as they see it) any opinions contrary to those of the mission must not be expressed if they do not want the danger of losing their positions through moral or economic pressure. On the other hand, missionaries often are not frank enough in expressing what they have in their hearts, because they fear to offend their sensitive brethren or appear superior over them. Identification of one group with the other, openly and in love as true Christians, is needed on both sides.

Toward New Understanding

Let me make four suggestions that might lead to better understanding between missionaries and nationals:

1. It is essential that all missionary candidates make a thorough study of the psychology and culture of the people whom they plan to serve, not only in general but of the specific area which is to be their field. Lack of knowledge and appreciation of Latin American psychology has contributed much to the problems between nationals and missionaries.

2. Since the work has now come of age, national leaders want to work as full collaborators with the missionaries. If mission boards truly wish to avoid misunderstanding, unfairness, and friction, they should formulate policies that give equal rights to all “citizens of heaven,” with ample opportunity for everyone’s views to be heard on a matter before decision is taken.

3. As funds permit, key national leaders from the different mission fields should be brought to the United States for brief visits. This may sound extravagant, but it would accomplish four important results: (a) leaders would be able to observe the operation of the church in the States, (b) they would learn to understand better the psychology of the Anglo-Saxon and his ways of work, (c) they would appreciate how a missionary feels in a strange country without a good grasp of the language, and (d) they would find out that money for missions, far from growing on trees, comes (to non-denominational missions at least) as a result of difficult semibegging on the part of the missionary. Such a trip would be an eye-opener to any national leader who loves missionaries and yet finds their ways at times difficult to understand.

4. In keeping with its increased growth and cultural development, Latin America needs missionary help today more than ever. Our thinking must be in terms of how we can make missions more effective rather than complaining that there is an “anti-missionary spirit” that must be retrenched. The fields of literature and radio, especially, are white unto the harvest. Missionaries must not desert Latin America now when only about 5 per cent of its 180,000,000 people are believers!

If any reader would visit the mission field to test the views that I have given here, he would be surprised at the high regard in which Latin American Christians hold those who have helped in any way to give them the message of peace.

In spite of the problems that still exist, it would be a sin to curtail the Latin American missionary program or stop sending help to countries where ignorance of the Gospel is so great.

Juan M. Isais is a native of Mexico. In 1951 he was graduated from Instituto Biblico Centroamericano, Guatemala. Since 1951 he has conducted weekly radio programs and served in evangelistic campaigns throughout Latin America. Currently he is assigned to mission responsibilities in New York City.