Of all danger areas facing religion and education today, the Western world’s college and university campuses are situated most vulnerably of all. Their neglect of Christianity has established them as vast temples of spiritual ignorance.

The Communist surge already has undermined the spiritual vitality and moral sensitivity of wide ranges of twentieth century intellectual life. Yet the majority of American educators remain profoundly indifferent to the inherited religion of the West. Thereby they imply the virtual irrelevance of Christianity as a world-and-life view to classroom concerns.

If an educator dedicated to Christian realities now constitutes an exception in academic circles, the professor who carefully delineates the bearing of Christian beliefs upon the content of class studies has virtually become an oddity.

From this neglect of the Christian heritage must result something far worse than a decline of denominational work among students, already distressing to many religious leaders. Loss of the intellectuals to the Christian cause means that the tide of creative thought is yielded to non-Christian, even to anti-Christian, minds. It means also that the Christian witness is mainly carried by those multitudes who, prizing Christianity as a religion of private devotion, do not sense its additional relevance to the spheres of society and culture as well.

This ominous prospect will worsen as enrollment in schools of higher education, currently totaling more than 3 million, doubles by 1967.

“Campus culture is not only not Christian, it is anti-Christian.… In fact, life and values on our campuses are further away from Christ and his church than those on the mission fields of Asia, since in the minds of students and faculty the church and Christian faith have been left behind …” These words are Edmond Perry’s, in an article titled “Search for Christian Unity on Campus” in the Methodist Student Movement magazine Motive (February, 1957). Many interpreters view Perry’s appraisal as more penetrating than Jones B. Shannon’s report in The Saturday Evening Post (March 29, 1958) of “a revival in religious faith” on the American college campus. Kermit L. Lawton of the Division of Evangelism of the Pennsylvania Council of Churches, completing a survey of 14 campuses in that state, thinks the religious response of students in state teachers colleges is best described by the term “spiritual neutrality.” Of 11,850 students of Protestant religious identification, only 2,181 (or 18.4 per cent) participate in college-town Protestant churches. Although the fact must not be overlooked that a growing number of commuter students now get a “suitcase” education, this is not a total explanation. Even in home churches, whose college age groups are slim and scanty to begin with, many pastors complain that college studies often put an end to enthusiastic participation of young people in church activities. American collegiate education imposes peculiar stresses upon the Christian outlook and seems swiftly to wither church interest on campus and at home.

Student indifference to university churches reflects a reaction to the pulpit ministry no less than a consequence of classroom lectures. Denomination after denomination the past generation zealously guarded its university pastorates for ministers whose eloquence and artistry blended with a passion to make Christianity acceptable to the modern mind. Their customary technique was to purge biblical religion of whatever ran afoul of modern presuppositions. What inevitably happened, of course, was that students (never underestimate their powers of critical analysis) soon sensed that these churches too had begun worshiping modern relativisms—which collegians could learn both more authoritatively and less disconnectedly in the classroom. Many university churches tended by the apostles of liberalism soon became religious shells lacking the Gospel glory.

Some off-campus churches preserved an illusion of vigor by providing inter-faith fellowships. This metamorphosis was experienced also on some campuses by the traditional Student Christian Association. The tide of religious inclusivism ran so strong that movements (such as Inter-Varsity Christian Fellowship) dedicated to a strictly evangelical witness in the service of Christianity as a religion of redemptive revelation were soon disparaged as exclusive and pietistic. More recently, Campus Crusade for Christ has recruited student converts also with spectacular success. Those who neglect the elementals of biblical faith have little ground for criticizing student effort which preserves such priorities as personal dedication to Christ as Saviour and Lord.

In a university atmosphere, however, spiritual commitment does not fully thrive while students ignore the larger implications of Christianity for the whole range of curriculum study. Must it not be acknowledged, however, that faculty more than students bear a responsibility to exhibit the historic relevance of the Christian world-life view? In this respect, student interest today often runs ahead of faculty inclination. To the professors more than to their pupils must be attributed an indirect if not direct responsibility for the frustration and demise of many Christian influences on campus. In the sphere of spiritual indifference, the modern masters have enlisted modern disciples.

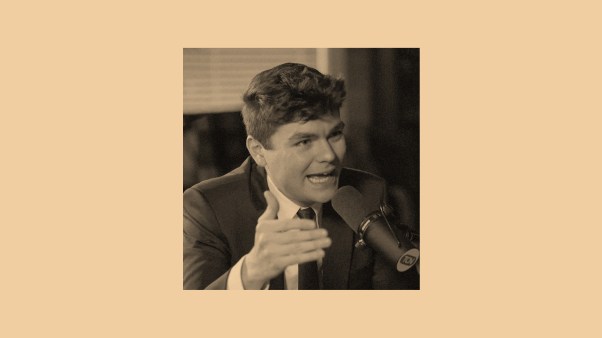

Recently in one of New England’s distinguished colleges, the president of the Christian Association addressed the campus community in a required chapel service. The speaker was Roger Hull, Jr. The chapel of every secular college in the West might well echo this college senior’s concern for Christian verities. There was an era in American campus life when a college president like Timothy Dwight would have said these things, and felt himself condemned were they unuttered. Today we may take heart because college students like Roger Hull, Jr., are voicing these great and timely convictions:

We have often been referred to as the uncommitted generation … criticized for our lack of commitment to any ultimate hope or transforming purpose beyond our own personal security and fulfillment. We seem to lack any sense of crusading spirit or sense of even local mission.

Our dilemma has recently been best summed up by Peanuts. He and Linus are discussing the matters of the world, and Linus remarks that when he grows up he wants to be a real fanatic. Peanuts questions Linus as to what he wants to be fanatical about. Linus replies, “Oh, I don’t know, it doesn’t really matter. I’ll be sort of a wishy-washy fanatic.”

Our student newspaper has attributed our lack of commitment (and our “I don’t know, it doesn’t really matter” attitude) to the relativistic atmosphere of our college education. The general attitude of our faculty seems to be one of reluctance to state to anyone what their own commitment or lack of commitment might be. At this point, I would like to ask them to do so either in this chapel, or through any other means they should consider appropriate.

Our Editor maintained that not only does our college not teach what ought to be in a moral sense, but it seldom recognizes the ability of anyone to state or know the validity of such statements concerning our existence.

Last Spring an attempt was made to fill this vacuum in our college community through a series of chapel talks designed to confront us with various areas considered to be worthy of our commitment. Yet, quite absent from our series was a consideration of commitment to the Person of Jesus Christ.

Today, merely as another student, I would like to suggest that the Person of Jesus Christ, in His life, in His death, and in His resurrection, is totally worthy of our commitment, and can deliver us from the despair of the uncommitted and seemingly directionless world, in which we find both ourselves and our society to be immersed.

The claim and the good news, if there be any, of the Christian Faith are that God has not left us to our own abstract speculation as to whether He exists, or what His nature might be.

The Christian Faith maintains that God Himself has come into the world in the historic Person of Jesus Christ. The Christian plea, when we would attempt to answer the question of the existence and the nature of God, is not what do you think of this or that system of philosophy, this or that system of ethics, or this or that system of dogma, but rather what do you think of the Person of Jesus Christ Himself.

The ultimate question we must answer when we assert the existence or nonexistence of God, or assume a position of agnosticism, is that question asked by Jesus Himself, not only whom do you say other men say that I am, whether it be your parents, your ministers, your teachers, or your roommates, but “whom do you say that I am?”

If nothing else, this question is at least answerable. In the New Testament Jesus Christ, both implicitly and explicitly, claimed to be the unique Son of God. He claimed that He and the Father were one, that He was the way, that He was the truth, and that He was the life and that no man came to the Father except by Him. In the 11th chapter of Matthew we read, “All things have been delivered to me by my Father, and no one knows the Father except the Son and anyone to whom the Son chooses to reveal Him.” So close did He consider His relationship with God, that to know Him was to know God, to see Him was to see God, to believe in Him was to believe in God, and to hate Him was to hate God. The egocentricity of this man’s claims is unparalleled in the history of the world. Yet, His life was filled with complete humility and self-sacrifice. As has been pointed out by the Rev. John Stott, it is this paradox of the self-centeredness of His teaching and the complete unself-centeredness of His behavior that is so baffling.

The nature of His claims and the nature of His behavior force us to answer the question of whether He was the unique Son of God. If He was not, then we must conclude that He was either the world’s greatest liar and fraud, or our supreme paranoid. I believe there can be no intellectually honest middle ground.

Due to the nature of His claims, the conclusion we come to becomes the singly most important decision of our lives, both now and for eternity. We can either accept or reject Him, but if there be any honesty in us, we cannot ignore Him.

Yet, in order to come to a decision concerning His question to us, “Whom do you say that I am?” and due to the order of its magnitude, we must at least seek Him with the same degree of effort and openmindedness that we employ in the daily study of one of our courses. It has been said that “God’s chief quarrel with man is that he does not seek.” Because we do not attend a lecture it does not mean that the lecture was not given. Nor, does the fact that we attend the lecture and fail to study and understand it mean that the lecturer did not know what he was talking about. You and I can seek Jesus Christ in the pages of the New Testament, and in the testimony and community of those who have found faith in Him.

If we assume a position of Christian Faith, agnosticism or atheism, in order to be in any way intellectually honest, we must have at least spent some serious days of study in the New Testament.

For those of us who have difficulty in accepting the New Testament documents as more than wishful projections of a few fishermen, I would again hope that we would have the honesty to determine for ourselves through firsthand study whether they be reliable or not, rather than on the basis of secondhand information and pure hearsay. The particularized nature of the accounts, their mutually verifying quality, and the inclusion of accounts no group of hero worshippers would ever include, give evidence of their reliability as actual history. However, even if we discredit the historicity of these documents, as John Stuart Mill has pointed out in his Three Essays on Religion, we have the even greater difficulty of explaining how a handful of completely uneducated fishermen could have concocted the sayings and imagined the life and character of this unparalleled person revealed in the New Testament.

For those of us who have difficulty in accepting those who have found faith in Him, I would hope that we would have the honesty and courage to admit that we are also imperfect and to realize that there is still someone who welcomes us in spite of all our imperfections, and in no way holds them against us.

I have committed my life to Jesus Christ as the Son of God. I can say with the deepest conviction that the reality of God’s presence and love in Jesus Christ is as real to me as your presence here this morning. By no means do I have the answers to all of life’s problems or to many of the objections to the Christian Faith. But one thing I do know, Jesus Christ has changed my life and made all things new. Where my life was once directionless and disturbed, it now has purpose and peace.

I ask you to consider earnestly and to answer the same question asked by Jesus Christ, “Whom do you say that I am?” I believe its answer is of eternal importance.

END

Seminaries Moving Students Into Church Activities

Ministers who recall the trepidation of their first pastorates, especially the anxieties of a first wedding or funeral service, will grasp the practical value of field work programs now projected by the seminaries. If internship is indispensable for prospective physicians, it may well nigh be so for prospective ministers. Such work bridges the gap between professional training, largely theoretical, and the practical issues of life.

One problem connected with internship is the time factor. Combining intern work with theological disciplines in a three-year course is most difficult. The enlarging responsibilities of church relationships face the student in a typical three-year theological program with unremitting pressures. Christy Wilson, who writes of the Princeton program in this issue, has said that a department of field work must be assured that divinity students are giving first place to their academic course, since their groundwork in the disciplines is basic. Some observers think the pendulum is now swinging too far in the direction of field education. They think the sacredness of the ministerial calling is somewhat cheapened when novices are hurried into important areas of service. Since the student comes as an intern, however, it should be easy to restrict his areas of responsibility.

One possible alternative is an intern program of a year following graduation, in which the student serves as assistant minister. Ordination might follow the completion of such internship, whereupon the graduate would assume his own pastorate. This at least would assure a full priority for the basic studies in a day when even divinity students seem to get by with a minimal exposure to the biblical languages and to biblical and systematic theology. The Presbyterian Church in the U. S. encourages students in its four seminaries to take a “clinical year,” usually between the second and third year of studies. Church history, theology, even the languages, become relevant and living when scholars are at work not simply with textbooks but with real people in life situations. Knowledge and practice must somehow be held together.

END

Anglicans Create New Church Office

Heralded as one of the most significant developments within the Anglican communion in years was the appointment of Episcopal Bishop Stephen F. Bayne, Jr. as Executive Officer of the world-wide Anglican communion. Represented in the Anglican communion are 15 autonomous church bodies. In the United States the Protestant Episcopal Church became a self-governing body in full communion with Canterbury during the year 1787. All Provinces recognize the leadership of the see of Canterbury, and it was at the invitation of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr. Geoffrey Francis Fisher, that Bishop Bayne accepted the newly-created post of Executive Officer. This new office will expedite cooperation between Anglican communions, but it is too early to judge whether this is a first step towards a world Anglican Church.

END

Strange Hymnody On The Riviera

According to Holiday magazine, the most popular numbers at Monte Carlo’s roulette tables are 17 and 29. What has this to do with the church? More than the churchman would care to believe. For it is further reported that in the English church in Monaco, no hymn with a number lower than 37 is sung, for fear that hunch-players in the congregation will rush out to back it. An American may be shocked at this, but he may not be smug. For in early New England the practice of betting on the numbers of the next Sunday’s hymns was not unknown, even if this was somewhat less disturbing to the decorum of the worship service than the quaint Monacan custom.

The lesson here for the Riviera hymnal compiler is quite evident—he must not serve his best vintage first. And if the Mediterranean sunshine must penetrate one’s reflection on an iniquitous state of affairs, he has to admit that in Monte Carlo they get people inside the church who most need evangelizing.

END