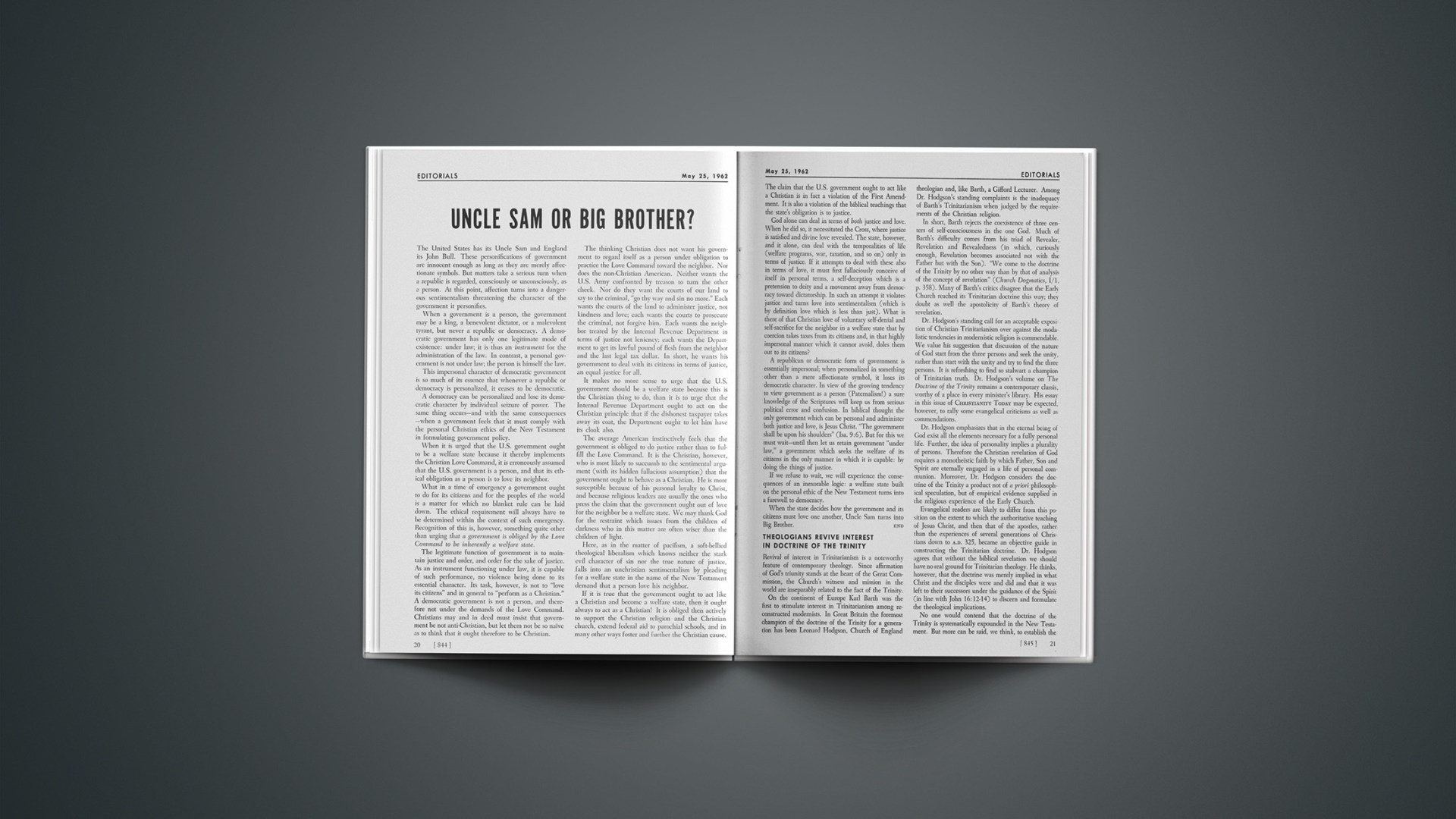

The United States has its Uncle Sam and England its John Bull. These personifications of government are innocent enough as long as they are merely affectionate symbols. But matters take a serious turn when a republic is regarded, consciously or unconsciously, as a person. At this point, affection turns into a dangerous sentimentalism threatening the character of the government it personifies.

When a government is a person, the government may be a king, a benevolent dictator, or a malevolent tyrant, but never a republic or democracy. A democratic government has only one legitimate mode of existence: under law; it is thus an instrument for the administration of the law. In contrast, a personal government is not under law; the person is himself the law.

This impersonal character of democratic government is so much of its essence that whenever a republic or democracy is personalized, it ceases to be democratic.

A democracy can be personalized and lose its democratic character by individual seizure of power. The same thing occurs—and with the same consequences—when a government feels that it must comply with the personal Christian ethics of the New Testament in formulating government policy.

When it is urged that the U.S. government ought to be a welfare state because it thereby implements the Christian Love Command, it is erroneously assumed that the U.S. government is a person, and that its ethical obligation as a person is to love its neighbor.

What in a time of emergency a government ought to do for its citizens and for the peoples of the world is a matter for which no blanket rule can be laid down. The ethical requirement will always have to be determined within the context of such emergency. Recognition of this is, however, something quite other than urging that a government is obliged by the Love Command to be inherently a welfare state.

The legitimate function of government is to maintain justice and order, and order for the sake of justice. As an instrument functioning under law, it is capable of such performance, no violence being done to its essential character. Its task, however, is not to “love its citizens” and in general to “perform as a Christian.” A democratic government is not a person, and therefore not under the demands of the Love Command. Christians may and in deed must insist that government be not anti-Christian, but let them not be so naïve as to think that it ought therefore to be Christian.

The thinking Christian does not want his government to regard itself as a person under obligation to practice the Love Command toward the neighbor. Nor does the non-Christian American. Neither wants the U.S. Army confronted by treason to turn the other cheek. Nor do they want the courts of our land to say to the criminal, “go thy way and sin no more.” Each wants the courts of the land to administer justice, not kindness and love; each wants the courts to prosecute the criminal, not forgive him. Each wants the neighbor treated by the Internal Revenue Department in terms of justice not leniency; each wants the Department to get its lawful pound of flesh from the neighbor and the last legal tax dollar. In short, he wants his government to deal with its citizens in terms of justice, an equal justice for all.

It makes no more sense to urge that the U.S. government should be a welfare state because this is the Christian thing to do, than it is to Urge that the Internal Revenue Department ought to act on the Christian principle that if the dishonest taxpayer takes away its coat, the Department ought to let him have its cloak also.

The average American instinctively feels that the government is obliged to do justice rather than to fulfill the Love Command. It is the Christian, however, who is most likely to succumb to the sentimental argument (with its hidden fallacious assumption) that the government ought to behave as a Christian. He is more susceptible because of his personal loyalty to Christ, and because religious leaders are usually the ones who press the claim that the government ought out of love for the neighbor be a welfare state. We may thank God for the restraint which issues from the children of darkness who in this matter are often wiser than the children of light.

Here, as in the matter of pacifism, a soft-bellied theological liberalism which knows neither the stark evil character of sin nor the true nature of justice, falls into an unchristian sentimentalism by pleading for a welfare state in the name of the New Testament demand that a person love his neighbor.

If it is true that the government ought to act like a Christian and become a welfare state, then it ought always to act as a Christian! It is obliged then actively to support the Christian religion and the Christian church, extend federal aid to parochial schools, and in many other ways foster and further the Christian cause. The claim that the U.S. government ought to act like a Christian is in fact a violation of the First Amendment. It is also a violation of the biblical teachings that the state’s obligation is to justice.

God alone can deal in terms of both justice and love. When he did so, it necessitated the Cross, where justice is satisfied and divine love revealed. The state, however, and it alone, can deal with the temporalities of life (welfare programs, war, taxation, and so on) only in terms of justice. If it attempts to deal with these also in terms of love, it must first fallaciously conceive of itself in personal terms, a self-deception which is a pretension to deity and a movement away from democracy toward dictatorship. In such an attempt it violates justice and turns love into sentimentalism (which is by definition love which is less than just). What is there of that Christian love of voluntary self-denial and self-sacrifice for the neighbor in a welfare state that by coercion takes taxes from its citizens and, in that highly impersonal manner which it cannot avoid, doles them out to its citizens?

A republican or democratic form of government is essentially impersonal; when personalized in something other than a mere affectionate symbol, it loses its democratic character. In view of the growing tendency to view government as a person (Paternalism!) a sure knowledge of the Scriptures will keep us from serious political error and confusion. In biblical thought the only government which can be personal and administer both justice and love, is Jesus Christ. “The government shall be upon his shoulders” (Isa. 9:6). But for this we must wait—until then let us retain government “under law,” a government which seeks the welfare of its citizens in the only manner in which it is capable: by doing the things of justice.

If we refuse to wait, we will experience the consequences of an inexorable logic: a welfare state built on the personal ethic of the New Testament turns into a farewell to democracy.

When the state decides how the government and its citizens must love one another, Uncle Sam turns into Big Brother.

Theologians Revive Interest In Doctrine Of The Trinity

Revival of interest in Trinitarianism is a noteworthy feature of contemporary theology. Since affirmation of God’s triunity stands at the heart of the Great Commission, the Church’s witness and mission in the world are inseparably related to the fact of the Trinity.

On the continent of Europe Karl Barth was the first to stimulate interest in Trinitarianism among reconstructed modernists. In Great Britain the foremost champion of the doctrine of the Trinity for a generation has been Leonard Hodgson, Church of England theologian and, like Barth, a Gifford Lecturer. Among Dr. Hodgson’s standing complaints is the inadequacy of Barth’s Trinitarianism when judged by the requirements of the Christian religion.

In short, Barth rejects the coexistence of three centers of self-consciousness in the one God. Much of Barth’s difficulty comes from his triad of Revealer, Revelation and Revealedness (in which, curiously enough, Revelation becomes associated not with the Father but with the Son). “We come to the doctrine of the Trinity by no other way than by that of analysis of the concept of revelation” (Church Dogmatics, I/1, p. 358). Many of Barth’s critics disagree that the Early Church reached its Trinitarian doctrine this way; they doubt as well the apostolicity of Barth’s theory of revelation.

Dr. Hodgson’s standing call for an acceptable exposition of Christian Trinitarianism over against the modalistic tendencies in modernistic religion is commendable. We value his suggestion that discussion of the nature of God start from the three persons and seek the unity, rather than start with the unity and try to find the three persons. It is refreshing to find so stalwart a champion of Trinitarian truth. Dr. Hodgson’s volume on The Doctrine of the Trinity remains a contemporary classis, worthy of a place in every minister’s library. His essay in this issue of CHRISTIANITY TODAY may be expected, however, to rally some evangelical criticisms as well as commendations.

Dr. Hodgson emphasizes that in the eternal being of God exist all the elements necessary for a fully personal life. Further, the idea of personality implies a plurality of persons. Therefore the Christian revelation of God requires a monotheistic faith by which Father, Son and Spirit are eternally engaged in a life of personal communion. Moreover, Dr. Hodgson considers the doctrine of the Trinity a product not of a priori philosophical speculation, but of empirical evidence supplied in the religious experience of the Early Church.

Evangelical readers are likely to differ from this position on the extent to which the authoritative teaching of Jesus Christ, and then that of the apostles, rather than the experiences of several generations of Christians down to A.D. 325, became an objective guide in constructing the Trinitarian doctrine. Dr. Hodgson agrees that without the biblical revelation we should have no real ground for Trinitarian theology. He thinks, however, that the doctrine was merely implied in what Christ and the disciples were and did and that it was left to their successors under the guidance of the Spirit (in line with John 16:12–14) to discern and formulate the theological implications.

No one would contend that the doctrine of the Trinity is systematically expounded in the New Testament. But more can be said, we think, to establish the doctrine itself more firmly as New Testament doctrine and hence as normative and authoritative for the religious life of the Early Church. Particularly in view of the difficulty of discriminating the three persons experientially in spiritual communion is it important to place adequate emphasis on that authoritative teaching which guided believers from the very outset. No doubt they did not fully comprehend its implications and in those first transition years Jewish Christians, in enlarging their monotheistic commitment to a trinitarian content, no doubt had to expand and revise theological concepts alongside their religious experience. But the finality and objectivity of that revision, we think, rested—to a greater extent than Dr. Hodgson seems to allow—upon authoritative teaching, first orally and then in the sacred writings.

The solid basis of trinitarian teaching is to be found not only in Christ and the Spirit, but in the biblical statements concerning them. Dr. Hodgson has “event” and “experience of it” (documented in the Bible) but no authoritative, normative statements as the essential basis of the later Chalcedonian development. Great texts like Matthew 16:16; 28:19; 2 Corinthians 13:14; and Romans 1:4, which speak of the Trinity or the deity of Christ or the Spirit, are decisive for Christian doctrine.

One may also call attention to the anthropocentric or Christianocentric elements in Dr. Hodgson’s presentation. This raises the basic problem Professor Barth deals with, whether we can make the three persons of Chalcedon into three personalities according to modern usage. If God is viewed imago hominis, we then end up with tritheism, which is fully as unscriptural as modalism (“modes of existence”).

Dr. Hodgson’s final emphasis is good, that we should finish the discussion of the Trinity, not in intellectual mystification but in doxology—not paradox but doxa! In this spirit the early post-Chalcedonian church produced great hymns to the triune God.

Compulsion, Not Compassion—That Is The Question

Almost unanimously the press, radio and television have censured the medical profession in general and a group of New Jersey doctors in particular for “inhumanity” and “refusal to care for the elderly needing medical aid.”

In keeping with election year temper, factual distortions and vivid generalities were called into play by politicians trying desperately to meet hastily conceived campaign promises. Welfare Secretary Abraham Ribicoff publicly deplored the New Jersey group’s “violation of professional oaths,” and his carefully worded blasts found a favorable “slant” at the hands of sympathetic newswriters and broadcasters. President Kennedy and Labor Secretary Goldberg made similar statements.

In attacking the doctor’s threatened “boycott,” the New Frontiersmen ignored the key promise contained in the doctors’ statement which stressed one point: Rather than accepting payment from patients who would receive taxpayers’ money under the King-Ander-son bill, “we will treat them free of charge.” Whether this is all virtue or part propaganda might be questioned. There can be little doubt, however, that by ignoring this part of the statement some politicians are practicing an age-old law of propaganda: “Repeat a half-truth loud enough and long enough, and it will gain general acceptance as fact.” Is it justifiable to attack the motives of an entire profession without objective presentation of all the facts?

A recent editorial in The National Observer states, “The problem of medical care for the aged deserves careful attention. It’s not going to be solved overnight by an ill-considered election-year scheme …”

Concessions To Universalism Blunt Evangelistic Urgency

The heresy of universalism—the doctrine that Christ’s redemption automatically embraces all men—continues to show its face on the theological scene, despite all protestations that Protestant theologians now view sin and salvation seriously.

Although Karl Barth has repeatedly denied the charge of universalism (as taught by Origin), Emil Brunner’s criticism—that Barth’s doctrine nonetheless eliminates judgment, condemnation and hell as real possibilities—needs to be heard. If all men are already embraced in the election of Christ, as Barth contends, then they lack only the removal of ignorance that they are saved, not faith and decision for Christ.

Recently Dr. D. T. Niles of Ceylon, general secretary of the East Asia Christian Conference, told the U.S. Conference for the World Council of Churches in Buck Hill Falls that “the task of evangelism is to bring out Jesus Christ in every man, not to put him in.” He assailed the common Christian characterization of adherents of other religions as “unbelievers.” Proceeding to Princeton Theological Seminary, Dr. Niles said that invitations to “accept Jesus Christ and be saved distort the Gospel.”

Even after the collapse of classic liberalism many modern theories of the mercy and righteousness of God reflect speculative adjustments of scriptural positions rather than authentic biblical theology. The Apostle Paul would have been greatly surprised to learn that his invitation to the Philippian jailer distorted the Gospel. Indeed, would he not have firmly established the counterpoint that the distortion is taking place further down the line?