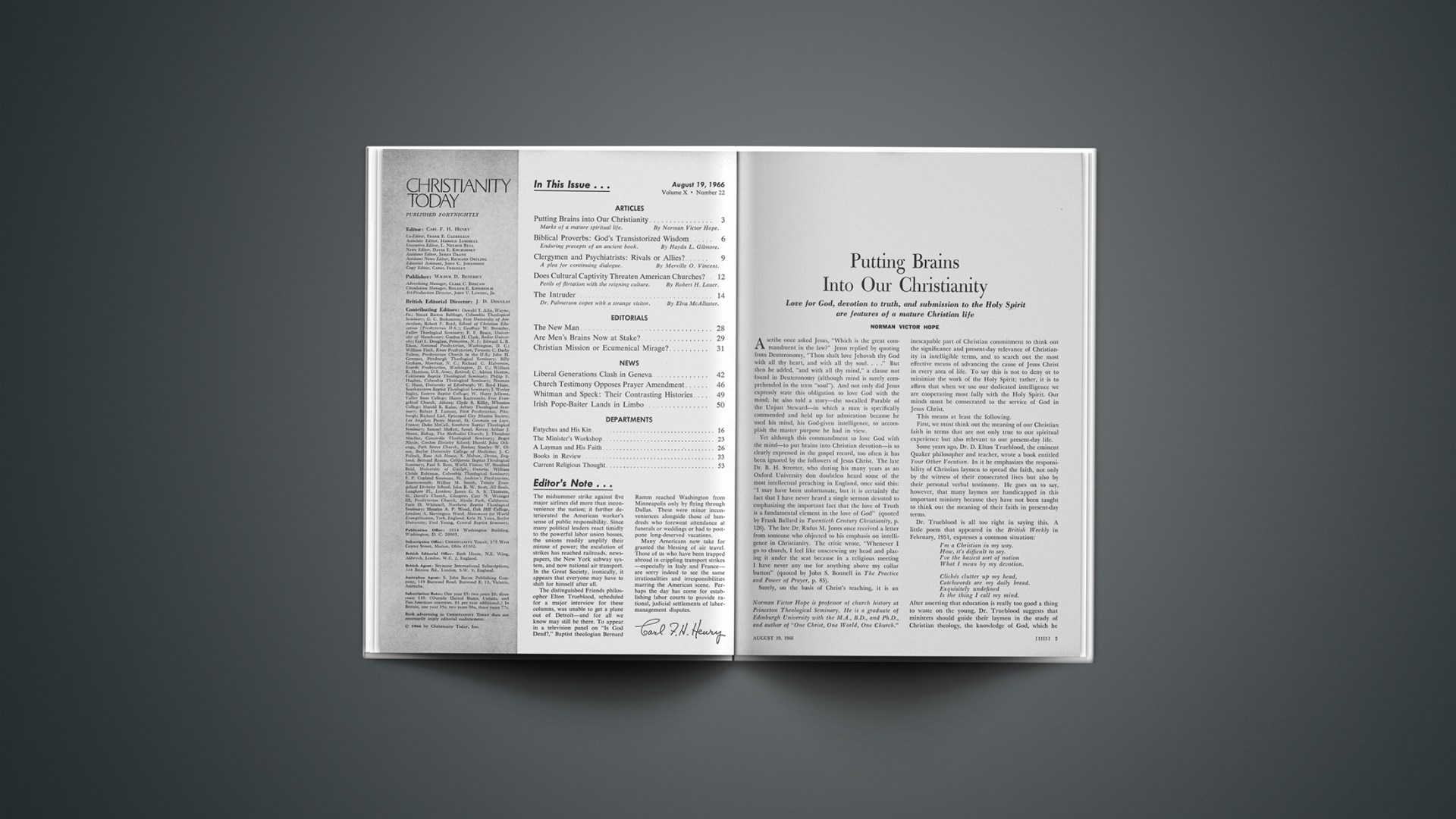

Love for God, devotion to truth, and submission to the Holy Spirit are features of a mature Christian life

NORMAN VICTOR HOPE1Norman Victor Hope is professor of church history at Princeton Theological Seminary. He is a graduate of Edinburgh University with the M.A., B.D., and Ph.D., and author of “One Christ, One World, One Church.”

A scribe once asked Jesus, “Which is the great commandment in the law?” Jesus replied by quoting from Deuteronomy, “Thou shalt love Jehovah thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul.… But then he added, “and with all thy mind,” a clause not found in Deuteronomy (although mind is surely comprehended in the term “soul”). And not only did Jesus expressly state this obligation to love God with the mind; he also told a story—the so-called Parable of the Unjust Steward—in which a man is specifically commended and held up for admiration because he used his mind, his God-given intelligence, to accomplish the master purpose he had in view.

Yet although this commandment to love God with the mind—to put brains into Christian devotion—is so clearly expressed in the gospel record, too often it has been ignored by the followers of Jesus Christ. The late Dr. B. H. Streeter, who during his many years as an Oxford University don doubtless heard some of the most intellectual preaching in England, once said this: “I may have been unfortunate, but it is certainly the fact that I have never heard a single sermon devoted to emphasizing the important fact that the love of Truth is a fundamental element in the love of God” (quoted by Frank Ballard in Twentieth Century Christianity, p. 126). The late Dr. Rufus M. Jones once received a letter from someone who objected to his emphasis on intelligence in Christianity. The critic wrote, “Whenever I go to church, I feel like unscrewing my head and placing it under the seat because in a religious meeting I have never any use for anything above my collar button” (quoted by John S. Bonnell in The Practice and Power of Prayer, p. 85).

Surely, on the basis of Christ’s teaching, it is an inescapable part of Christian commitment to think out the significance and present-day relevance of Christianity in intelligible terms, and to search out the most effective means of advancing the cause of Jesus Christ in every area of life. To say this is not to deny or to minimize the work of the Holy Spirit; rather, it is to affirm that when we use our dedicated intelligence we are cooperating most fully with the Holy Spirit. Our minds must be consecrated to the service of God in Jesus Christ.

This means at least the following.

First, we must think out the meaning of our Christian faith in terms that are not only true to our spiritual experience but also relevant to our present-day life.

Some years ago, Dr. D. Elton Trueblood, the eminent Quaker philosopher and teacher, wrote a book entitled Your Other Vocation. In it he emphasizes the responsibility of Christian laymen to spread the faith, not only by the witness of their consecrated lives but also by their personal verbal testimony. He goes on to say, however, that many laymen are handicapped in this important ministry because they have not been taught to think out the meaning of their faith in present-day terms.

Dr. Trueblood is all too right in saying this. A little poem that appeared in the British Weekly in February, 1951, expresses a common situation:

I’m a Christian in my way.

How, it’s difficult to say.

I’ve the haziest sort of notion

What I mean by my devotion.

Clichés clutter up my head,

Catchwords are my daily bread.

Exquisitely undefined

Is the thing I call my mind.

After asserting that education is really too good a thing to waste on the young, Dr. Trueblood suggests that ministers should guide their laymen in the study of Christian theology, the knowledge of God, which he says is the most mature discipline in which men and women can engage.

Asking Hard Questions

He goes on to specify some of the difficult questions which this kind of study should confront: On what grounds does the Christian justify belief in the uniqueness of Christianity, when there are certain elements of truth in the teaching of other world religions? How does the Christian believe in the efficacy of intercessory prayer and yet at the same time believe that there is an objective order of natural law that makes possible the scientific prediction of events? How does he justify belief in both the goodness and the power of God, when so many innocent people suffer with such obvious injustice and without profit to themselves or others? How can he believe in the evidential value of the widely reported direct experience of God, when it appears that such experience is purely subjective or can be explained in psychological terms? This effort to work out a reasoned faith, marked both by scientific integrity and by evangelical vigor, is one aspect of our Christian obligation to love the Lord our God with all our mind.

Secondly, it is our duty to think out how to apply our Christian faith most effectively to every situation that confronts us. Each Christian faces a daily combination of circumstances peculiar to him; he must determine the way in which his faith can best operate in those circumstances.

A story told by Andrew D. White, United States ambassador to Russia during the later years of the nineteenth century, illustrates this point. He tells of walking down the Nevsky Prospect in St. Petersburg, then the capital of Russia, with Leo Tolstoy. In their walk they encountered a number of beggars asking for alms, and to each Tolstoy gave a kopeck. Dr. White protested that this indiscriminate charity encouraged the creation of a dependent and debauched population, which was one of the gravest social problems of the day. Tolstoy’s reply was that it was not his business to consider the consequences of his action, and that the Gospel of Jesus Christ said simply, “Give to him that asketh thee.” It was his duty, he said, to obey the Gospel without considering the consequences.

But Tolstoy was quite wrong. It most emphatically is the Christian’s business to think out the consequences of his actions. Before acting he must be as sure as he can be that what he does will make the greatest possible contribution to the Christianization of men. Sometimes his duty will be to give all he can, poor though he may be. But at other times his duty will be to refuse to give money—even though he may be wealthy—and try to aid needy people in some other way, such as helping them get a job.

Preacher In The Red

THANKS TO ALL

It was the young minister’s first funeral service. Although the man who had died had not had a very commendable reputation, a fairly large crowd came to pay their last respects. All were curious to hear the new minister’s message. The text was well chosen and fitting words were spoken, but at the graveside it seemed that something had been forgotten. The undertaker stepped to the minister when the benediction had been pronounced and whispered something in his ear. The minister took the cue and with strong voice said, “I have been asked to announce that the family would like to have me thank all those who have helped to make this funeral possible.”—The Rev. JOHN NIEUWSMA, pastor, Ebenezer Reformed Church, Morrison, Illinois.

War: Can Christians Take Part?

The Christian encounters another aspect of this principle when he tries to determine the attitude he should have toward war. The question of war, which is the most pressing public question in our world, is peculiarly difficult for Christians, since they agree that war is contrary to the mind of Jesus Christ, their Lord and Redeemer. Some have contended that the question is answered by the saying of Jesus Christ in the Sermon on the Mount: “Resist not evil.” This is Christ’s own word on the matter, these persons say, and it should prevent any Christian from participating in war in any way.

But on a deeper and sounder interpretation of the mind of Jesus Christ, this utterance alone—though it is very important and must be considered carefully—cannot be allowed by itself to determine the final Christian attitude toward war. The Christian will, of course, do all in his power, both individually and in cooperation with other Christians, to prevent war; he will indeed be willing to make all kinds of sacrifices for this end. But if war should break out, he will then have to consider most carefully the consequences of any proposed attitude toward it; and if he should decide, after careful and prayerful reflection, that the results of abstaining would be less Christian than the results of participating, then, with however heavy a heart, he will be bound to participate. Thus he will choose what for him is the lesser of two evils.

These are only two examples of the general proposition that it is our business as Christians to think out how our faith may best be expressed in each situation that confronts us.

Thirdly, it is our duty to think out the most effective means by which to spread the Christian faith in the present-day world. One of the basic and inescapable tasks of the Christian Church is so to present Jesus Christ to men and women that they surrender to him as Saviour and serve him as Lord in the fellowship of the Church. This task is known as evangelism. And one of the most encouraging features of present-day church life is that churches—not only the store-front groups but also the standard brands—are becoming interested in evangelism as they have not been in many years. They are realizing what is surely the truth, that the Church that does not evangelize will fossilize.

Now, in order to evangelize most effectively, two things are needed; first, a deep heart-devotion to the Lord Jesus Christ, and secondly, the ability and willingness to think out the most convincing ways of presenting his Gospel to the unevangelized.

History serves to confirm this truth. The Apostle Paul, for example, conducted his great evangelistic campaigns by going to the great cities of the Roman Empire, those strategic centers from which religious influences radiated to the hinterlands. And in the cities he started to preach in the Jewish synagogues, where for some years there had been growing up a large fringe of Gentiles who were deeply interested in the Jewish religion because of its doctrine of one sovereign God and its high ethical standards. There, in those synagogues, Paul could count on a favorable reception; and from such Gentile “God-fearers,” as they were called, came many of the earliest Christian converts.

Again, in the sixteenth century, Luther spread his great Reformation revival, first by translating the Bible into the vernacular language of his German people, and then by writing short, pithy tracts in German to expound his point of view. These tracts of Luther circulated not only throughout Germany but over a large part of Europe and unquestionably did much to win converts for Protestant New Testament Christianity.

Then in the nineteenth century, D. L. Moody, who according to one comment “reduced the population of hell by one million,” not only preached the Gospel in a vivid, pointed style, so as to bring his hearers to the point of decision, but also persuaded Ira D. Sankey to play and sing gospel hymns in order to present Christian truth in song. In addition, Moody set up organized inquiry rooms where those who wished to decide for Jesus Christ could be led into an understanding acceptance of him and could be shown how to grow in grace and in the knowledge of their Lord and Saviour.

Using Mass Media

This age in which we live is very different in many ways from that in which Paul lived and from Luther’s sixteenth century and Moody’s nineteenth. The Gospel we proclaim is of course the same: our Lord Jesus Christ is the same yesterday, today, and forever. But we are obligated to think out the most effective ways to present Christ to the men and women of today. We shall have to employ those tremendous media of mass propaganda—the press, the movies, the radio, and television—that modern science has placed in our hands, as Billy Graham and others are doing. If these media are not used for good, they will most assuredly be used for evil.

Finally, it is our duty to think out how Christianity can be applied most effectively to the problems of group relations.

One fact frequently pointed out by thoughtful readers of Scripture is that the New Testament has virtually nothing to say, at least explicitly, about the problems that arise out of the existence of social groups. Dr. T. E. Jessop, that thoughtful English Methodist layman and professor of philosophy, has written a book entitled Social Ethics, Christian and Natural, in which he draws attention to this general fact and specifies several such problems. Among the questions he raises are these: (a) How should a group—a labor union, say, or a government, a nation, or the United Nations—behave? What principles should govern the actions of such bodies? (b) How should an individual behave while acting as a member of a group—as a citizen, for example, or as a member of a labor union that is taking a strike vote? (c) How should an individual behave when he acts as the representative of a group—as, for example, a member of Congress, or a wage-negotiator?

Freedom Brings Responsibility

The Bible in general, and the New Testament in particular, has little or nothing to say about specific rules of conduct for such situations as these. Doubtless the main reason for this absence lies in the twofold fact that most such groups did not exist in New Testament times and that, in any case, the government under which all New Testament Christians had to live was a totalitarian dictatorship that demanded obedience, not responsibility.

But today this situation has changed greatly, at least in all those countries that are not behind the Iron or Bamboo Curtain. The Christian of today, whether he likes it or not, has to live in a world of social groups. It is therefore his Christian obligation to think out the methods by which his Christianity may most effectively be brought to bear upon group situations; and in order to do this, he will have to rack his brains as well as say his prayers.

In John Bunyan’s allegory, The Pilgrim’s Progress, Mr. Greatheart’s party on the road to the Celestial City finds an old man, obviously a pilgrim, asleep under a tree. They awake him and ask him who he is. Somewhat resentful at being disturbed, he replies that his name is “Honest” and that he comes from the town of “Stupidity.”

Then says Mr. Greatheart to him, “Your town is worse than the city of Destruction itself.” This is Bunyan’s vivid and picturesque way of stating the New Testament truth that the Christian is obligated to love the Lord his God, not only with all his heart and soul and strength, but also with all his mind.