Can Christianity survive and thrive in large cities? This is an urgent question for evangelicals as they enter the 1970s for four reasons:

First, the city is now our largest mission field. In the last fifty years the human race has engaged in a worldwide mass migration to cities. Between 1900 and 1950 the population of our planet increased 49 per cent, but the population of cities rose 200 per cent. The United States, which was 90 per cent rural in 1790, will be 90 per cent urban in 1990. The urbanization of our planet means that we live, as Lewis Mumford has written, in “a world that has become, in many practical aspects, a city.” If successful mass evangelism is going to occur in the future, it will happen in cosmopolis, the “world city.” In the face of this vast opportunity, do evangelicals have enough spiritual momentum to pioneer the greatest missionary frontier in church history?

Second, the city poses a communication barrier for the churches. If effective witnessing is going to occur in 2001, it will have to be in language that city-dwellers can understand. The language of the evangelical churches, however, has often been rural. The minister is a “pastor” or “shepherd” who serves people called “the flock” or “the sheep.” The message is of a “Good Shepherd” named Jesus who drew his symbols from the countryside—the lilies of the field, the birds of the air, the foxes in their lairs. His parables speak of seedtime and harvest, laborers in the vineyard, the wheat and the tares, the sheep and the goats, the barren fig tree, the vine and the branches, the shepherd and the sheep, the lost lamb, the mustard seed, and the young leaves of the fig tree. Can evangelicals effectively employ the rural vocabulary of the Bible in megalopolis? Do we also possess a persuasive urban style?

Third, the city challenges the Church with the need to preach a meaningful message to metropolitan man. Yet historically the evangelical churches in the United States have been rural in orientation. American Protestantism was the faith that followed the frontier. Baptists, Methodists, Disciples, and Presbyterians won converts by ministering to restless men on the westward movement; Lutherans, Reformed, and Moravians retained the loyalty of farm folk from the Continent; Congregationalism was the religion of the Yankee township; and the Episcopal Church was strong among tidewater settlers in the South. When America was predominantly rural, the evangelicals had a message that was eminently relevant. Do they have an equally valid and vital word for an urbanized America?

Fourth, the city is in need of redemption. This is the witness of the daily news report. It is also the testimony of the Scriptures. The Bible portrays the evil potential of a city organized apart from God. The murderer, Cain, fleeing from the presence of God, founded the first city (Gen. 4:17). These “tainted origins” often bore bitter fruit. A secular, urban society existed before the Flood, but “the earth was filled with violence” (Gen. 6:11) and invited divine destruction. After the Deluge, the sons of Noah forgot the judgment and said, “Come, let us build ourselves a city, and a tower with its top in the heavens, and let us make a name for ourselves …” (Gen. 11:4). The lesson of Babel was lost by the age of Abraham, as the devastation of Sodom and Gomorrah reveals (Gen. 19). Throughout the Old Testament there is the theme of God’s wrath against the secular city, as is illustrated in the histories of Jericho, Nineveh, Babylon, and even Jerusalem. One of the most moving episodes in the New Testament is that of the Saviour weeping over David’s City for “killing the prophets and stoning those who are sent to you!” (Matt. 23:37). Within seventy years it would be destroyed by Roman legions. These events prove the truth of the words of the psalmist, that “unless the Lord watches over the city, the watchman stays awake in vain” (Ps. 127:1). They also pose this question: Can evangelicals confront cosmopolis with Christ so that there can be opportunity for repentance and redemption?

It is good that evangelicals are concerned about the city. This concern can become hope if we discover that while much of the biblical-evangelical tradition is indeed rural, it is not exclusively so. We also possess a rich but neglected urban heritage. The pathfinders and pioneers of our faith have blazed a path into the city for us. The Lord has led the prophets, apostles, and reformers into metropolis. Christ is already at home in cosmopolis. Our task is not to invent an urban theology or a secular, suburban gospel, but instead to make our Saviour’s presence known. We can plan for our future in the city, then, by rediscovering four aspects of our past:

1. The Bible may begin by placing man in a rural setting, the Garden of Eden, but it ends with St. John’s vision of a bright urban vista, “the holy city, new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband …” (Rev. 21:2). A central theme of the Scriptures, therefore, is the movement of the Word of God from the country to the city. This evangelistic momentum is revealed in the history of Israel, the career of Christ, and the life of the apostolic church.

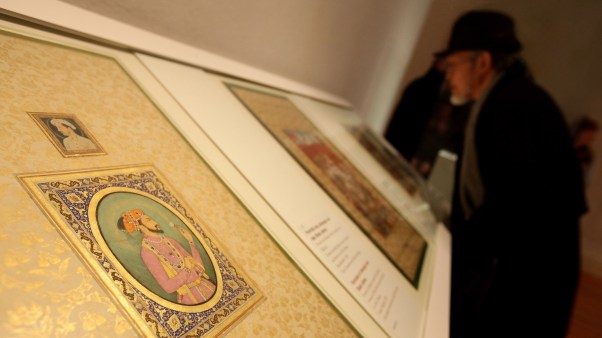

A forgotten aspect of the history of Israel is the repeated pilgrimage of God’s people from “the desert to the town.” The patriarchal period, which began with the wilderness wanderings of Abraham, ended in the urbanization of the Hebrews under Joseph in Egypt. A second turning point of Hebrew history was the migration of the Israelites from the deserts of Sinai into the cities of Canaan. The Book of Judges reports the process by which a nation of nomads became a settled community. The tribal confederation was converted into a kingdom and the tent-tabernacle became an urban temple. Later the exile was a further step in the urbanization of God’s people. An elite from the Southern Kingdom was taken to the “city of cities,” Babylon, a name that is still a synonym for megalopolis. This was the beginning of the dispersion. By the time of Jesus, only one-fourth of the world’s Jews lived on the land in Palestine. Most of them resided in large cities, like Alexandria, Antioch, and Rome. This infusion of Israel into the mainstreams of pagan society gave the Hebrews the opportunity to be “a light to lighten the Gentiles.” These islands of biblical faith served as bridges for the Christian Gospel from rural Palestine to the urbanized Roman world.

As the people of God left the land for the city, the prophets of the Lord followed with the Word. We have often associated the prophetic tradition with the desert, but this is only partially true. Didn’t Moses leave the wilderness home of Jethro to appear in the courts of Pharaoh? After this the messengers of God went into the urban world with the Word, as Nathan to the court of David, Elijah to the house of Ahab, Elisha throughout Israel to protest the worship of the Phoenician god Baal, Jeremiah to an endangered Jerusalem, and Jonah to distant Nineveh. Metropolitan prophets also made their advent, as Isaiah, the “Paul of the Old Testament,” who had his beatific vision not in the silence of the desert but within the walls of the urban temple.

In many respects the life of Christ recapitulates the history of Israel. In his career, therefore, there is a movement from the country to the city. Though born in rural Bethlehem and raised in agrarian Galilee, Jesus took the Word to the cities. Unlike his predecessor, John the Baptist, who was a country preacher, Jesus deliberately ventured forth into the urban society of his time. We find him centering much of his ministry in Capernaum, an important military center in Galilee and the location of the customs station from which the Master called Matthew to be an apostle. Christ, however, did not confine his labors to one community, for when the people “would have kept him from leaving them … he said to them, ‘I must preach the good news of the kingdom of God to the other cities also; for I was sent for this purpose’ ” (Luke 4:42, 43). The Gospel was proclaimed in the Gentile cities of the Decapolis and in the region of Tyre, Sidon, and Syrophoenicia. The climax of our Saviour’s career came when he pointed the way southward from Galilee toward Jerusalem.

Christ’s childhood was spent in the country, hidden from the eyes of men, but his ministry was fulfilled in the city, before the eyes of the world. It was outside a city, Jerusalem, that Jesus was crucified. While one sacrament, baptism, has a rural origin by the banks of the Jordan, the other, the Lord’s Supper, was instituted in an urban apartment. The passion history, which occupies almost half of each of the four Gospels, is entirely urban in its setting. It was in the city that Jesus was betrayed, arrested, tried, and mocked. As he had ridden into the city on Palm Sunday to inaugurate the passion, so on Good Friday he walked its streets to the suburb of Golgotha where he offered his life as the sacrifice for sin. Three days later, in a graveyard outside the walls, he arose. Thus both of the central mysteries of the Christian religion, the crucifixion and the resurrection, occurred in the vicinity of a city. This is God’s most eloquent witness to urban man! The life of Jesus—from birth in the basement of a crowded highway motel to death and resurrection outside a city filled with holiday visitors—is one of witness to urban man.

The same dynamic is discovered in the New Testament Church. The twelve apostles, except for Judas, were all from the country. They realized, however, that Christianity was “good news for all people” and that the Church must be where the people are. The world of the apostles was an urban one. Professor Lynn Thorndike characterized the Roman Empire as “essentially a league of cities.” Furthermore, the Holy Spirit left no doubt in the minds of the apostles as to where their mission was, for the Church was born in a townhouse in the heart of Jerusalem. The first Christian sermon was delivered on the city’s streets. Koiné, the tongue of the towns, not Aramaic, the language of field and farm, soon became the speech of sermon and Scripture. The name Christian was first received in a city, Antioch, often called the second home of Christianity. The expansion of the new faith was to be in the urban areas of the Roman Empire.

The best illustration of the urbanization of the early Church is Paul. If the apostles Christ called when he was in the flesh were country folk, the first to be called by the ascended Lord was a city-dweller, Paul. He was born and raised in the city of Tarsus and educated from the age of thirteen in the theological seminary at Jerusalem; a citizen of Rome, he was converted outside Damascus, which according to tradition is the world’s oldest city. Paul started his ministry by serving a polyglot congregation in Antioch. He followed this with missionary tours and letters in the heavily populated urban centers of the empire. This apostle’s life can be outlined by a roster of cities—Colosse, Philippi, Corinth, Athens Antioch, Ephesus, Jerusalem, Rome. The poet’s words surely apply to Paul:

The man of many shifts, who wandered far and wide,

And towns of many saw and learned their mind;

And suffered much in heart by land and sea,

Passing through wars of men and grievous waves.

New Testament Christianity, therefore, though rural in inception, has within it a mighty spiritual momentum that has enabled it to convert men of cities.

2. As evangelicals face the crisis of cosmopolis, it is essential to recover the powerful language of the Bible.

To win cosmopolis, we must begin by rediscovering our biblical symbols. Certainly many of them are rural in origin, but this has never prevented the Church from succeeding in cities. The Roman world was urban, yet the earliest and most popular and wide-spread image of Christ was that of the Good Shepherd. Furthermore, we must remember that the very Gospels that abound in rural language were pretested as preaching on urban audiences by Peter, Paul, John, Luke, and Matthew. Indeed, the Gospels were written at the prompting of the Spirit to be used as urban missionary literature. The Gospel of Matthew may have been originally employed as a catechism or convert manual in the cities. Mark’s Gospel is believed to be an anthology of Peter’s sermons delivered in Rome. Luke’s Gospel and History preserve the witness of the Spirit through Paul—a ministry that was predominantly metropolitan. John has given us the theology of Christ in Gospel, Letter, and Prophecy cast in the language of the urban church and academy—so simple as to move even the illiterate and yet so profound as to amaze the philosopher.

Surely the apostolic writers realized the difficulties inherent in using rural language before an urban audience. But they were even more aware of a greater reality. Christ, in his parables and sayings drawn from rural life, had opened up the basic experiences of sin and grace. The Word, though incarnate in the language of the country, is a saving message from God addressed to the human predicament. It is therefore so basic and universal that it transcends the urban-rural dichotomy. Because the words of Christ speak directly to our human condition, they cannot be limited merely by language to any time or locality. Our task, therefore, is neither to abandon nor to recast the Word of God—even when it is spoken in the rich imagery of farm, field, and village. Such an effort to separate “kernel” from “husk” would be a very denial of the Incarnation, that God did become flesh in a specific era and area and used the language of that time and place. Our Christ is not some ethereal discarnate ghost, as in the heresy of ancient Docetism; he is a Lord who “became incarnate” and who can be located in history and geography as well as in eternity. Our primary mission is to return to the Word and preach the simple but profound message that speaks to the hearts of men in all manner of environments.

As we recover the biblical message we will soon discover that the critics have exaggerated the rural flavor of the New Testament. Beside the language of the land there also stands much urban imagery. Jesus spoke of the city set on a hill and told of a prodigal son who left the farm to waste his inheritance on fast women and good times in the big town in the far country. The Master discussed the idle unemployed in the urban marketplace waiting for work in his parable of the laborers in the vineyard. His lips report the contrast between urban opulence and poverty in the parable of Lazarus and Dives. The Saviour was aware of such urban problems as the unpredictable conduct of kings, the presence of unjust judges, the dilemma posed by Caesar’s taxation, the cunning of crooked but clever stewards, the nuisance of a noisy neighbor at midnight seeking provisions, and the desperate plight of the widows. And lest we forget, the Saviour’s craft was that of carpenter—an urban occupation. He spoke equally well the language of town and of country. So must we.

Paul certainly put the Gospel in urban language. Aware of city man’s fascination with spectator sports, he referred to the foot race, the winner’s crown, wrestling, shadow-boxing, and other athletic events. Realizing the importance of the military in urban life, Paul described the spiritual warfare of Christians and spoke of the virtues by comparing them to pieces of a soldier’s equipment. A tentmaker by trade, Paul employed the images of market and shop to describe the Gospel, writing of slaves, the potter and the clay, the teacher, and “God’s handiwork.” As one reads the letters of Paul, he is impressed with the fact that hardly any aspect of urban life escaped the observant eye of the apostle.

Twenty centuries later as we venture into the city we need not, like Moses, grope for words. The Gospel has already been “urbanized.” This occurred in its very inception. If our preaching is true to the Word, Christ will be able to reach the man of the modern cosmopolis.

3. As we face the crisis of cosmopolis, we must recall that evangelical theology is the relevant Word modern man needs to hear.

The tragedy of our cities is that of a loss of community. The earthly Babylon is fast becoming a chaotic Babel. Our cities, like our sprawling suburbs, have no real center left. But to have community, with appropriate communication, we must have something or somebody “in common.” The quality of a community depends on who or what is at its heart—for that determines its nature, purpose, direction, and destiny. Divided by ethnic, racial, social, cultural, educational, religious, and economic forces, our polyglot urban populations have no shared characteristics except frustration, alienation, and a haunting sense of meaninglessness. To lost and lonely individuals, striving to arrive at some kind of coexistence or collective life, the evangelical faith offers hope. This is one of a new community that has at its heart a person, Jesus Christ. He alone has the power to reconcile Jew and Gentile, black and white, male and female, affluent and deprived—because he alone can overcome the curse of Cain, the father of the city. Christ restores us to fellowship with God. Just outside the city wall he shed his blood to absorb in his body both God’s judgment on man’s sin and humanity’s deep sense of frustration. Jesus, the second Abel, has offered his life as a perfect sacrifice so that his urban brothers may be saved. There is no more meaningful message for modern metropolitan man than this.

4. This is the Word that is powerful enough to redeem man’s cosmopolis and make it into “the city of God.” Though the city was founded by Cain as a place for refuge from God, the destiny of cosmopolis is to be cleansed and to become the abiding place of Christ and his saints. The tragedy of Genesis will be transformed into the eternal metropolitan joy envisioned by St. John the Divine in the Revelation:

And I saw the holy city, new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband; and I heard a great voice from the throne saying, “Behold, the dwelling of God is with men. He will dwell with them, and they shall be his people, and God himself will be with them; he will wipe away every tear from their eyes, and death shall be no more, neither shall there be mourning nor crying nor pain any more, for the former things have passed away” [Rev. 21:2–4].

This is our ultimate destiny. Let us boldly witness so that cosmopolis becomes neither Babylon nor Babel but an anticipation of the New Jerusalem.