A Thorough Outline

A Biblical Theology of Missions, by George W. Peters (Moody, 1972, 368 pp., $6.95), is reviewed by Robert Brow, Anglican rector of Millbrook, Ontario.

This book by the professor of world missions at Dallas Seminary is a necessary addition to every Bible school and seminary library. Its subheadings and numbered points will be appreciated by students but do not encourage bedtime reading.

The first five chapters thoroughly outline the idea of mission in the life and teachings of Jesus Christ and in the Old and New Testaments. There is a distinction between the mandate to Adam—“the qualitative and quantitative improvement of culture on the basis of the revelational theism manifested in creation”—and the mandate for mission through the Church. Peters clarifies the latter by giving a helpful exegesis of the great commission in the four Gospels.

Field missionaries will note the lack of a thorough discussion of the theology of Roland Allen and Donald McGavran in the brief chapter on missionary societies.

A chapter entitled “The Instruments of Missions” gives one view of the relation of the apostles and prophets of the New Testament to modern missionaries. Peters argues for the continuance of two kinds of missionary: evangelist-church planters, and pastor-teachers. The former are successors of the apostles, but without Paul’s apostolic authority. The latter are “functional successors” to the prophets, but without the function of teaching “under the immediate influences of the Spirit.” It is pastor-teachers who are mainly needed as the “contribution of the older churches to the younger churches.”

The distinction between the call to a ministry of the Word and secular callings (farmer, businessman, banker) is very sharply drawn. Peters’s theology makes him very suspicious of the man who turns from “the ministry of the Word” to “some other type of service or profession.”

A final chapter touches on the relation of the Gospel to other religions. Peters contents himself with a twelve-point summary of the biblical view. He notes but does not directly discuss the various views of mission that are current in ecumenical circles.

Two Views Of Black Religion

The Black Preacher in America, by Charles V. Hamilton (Morrow, 1972, 246 pp., $7.95), and Black Sects and Cults, by Joseph R. Washington, Jr. (Doubleday, 1972, 176 pp., $5.95), is reviewed by J. A. Parker, director, American Speakers Bureau, Washington, D. C.

Both volumes promised to remind me so much of growing up that I could hardly wait to begin reading them. Like Charles Hamilton, I grew up in a black Baptist church. Hamilton romped in south Chicago and I in south Philadelphia. I have many relatives, friends, and acquaintances who are members and supporters of a great number of “black sects and cults”: Baptists, Methodists, Sanctified Holiness, Father Divine, Daddy Grace, African Orthodox, Church of Our Lord Jesus Christ of the Apostolic Faith, and many others. The names may seem more exotic, but it is no more difficult associating with these worshipers than their white Lutheran, Assemblies of God, Presbyterian, and Episcopal counterparts.

Hamilton gives readers many brief but important insights into black American preachers, including Nat Turner, Benjamin Mays, Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., Joseph H. Jackson, Jr., and Martin Luther King, Jr. It is predictable that someone of Hamilton’s persuasion (he co-authored Black Power with Stokely Carmichael) would find fault with these men.

Hamilton could not resist mentioning the intense and fundamental disagreement between Joseph Jackson, longtime president of the National Baptist Convention, Inc., and pastor of the Mount Olivet Baptist Church in Chicago, and the late Martin Luther King. Hamilton correctly notes the strange allegiance to both Jackson and King by the members of Mount Olivet and the National Convention. It was not at all unusual for Jackson to denounce King as an undesirable troublemaker from his pulpit, only to have many of the flock attending a King rally a day or two later. The people apparently viewed Jackson as their “salvation” preacher and King as their “civil rights” preacher. Hamilton points out that “even though King and Jackson had much disaffection for each other the membership did not get involved.” Nevertheless King sided with those who led in the formation of the Progressive National Baptist Convention of congregations formerly associated with Jackson’s denomination.

Black Sects and Cults is another in the C. Eric Lincoln series of books about the black religious experience. Washington does a fair job of cataloguing numerous religious groups. Unfortunately, like many other writers, he unwarrantedly generalizes from specifics. Washington feels that “the distinguishing characteristics of these diverse religious groups is a common concern for power.” Like many radical clergymen, he ignores previous attempts and proposes a “black theology” that can galvanize the black sects and cults to “serve the real needs of the black community.” It would be instructive for Washington to consider the Jackson-King conflict and its implications for any unifying “black theology.”

School Thoughts

Reshaping Evangelical Higher Education, by Marvin Mayers, Lawrence Richards, and Robert Webber (Zondervan, 1972, 215 pp., $6.95), and About School, edited by Mark Tuttle (Houghton College Press, 1972, 144 pp., $2.50 pb), are reviewed by Robert H. Mounce, assistant dean of arts and humanities, Western Kentucky University, Bowling Green.

When these two books arrived for review, it seemed natural to begin with the larger hardback, assuming it would be the more important. It wasn’t! Like so many cooperative writing projects, it lacks continuity and direction. I am less than hopeful that it will be a significant force in “reshaping evangelical higher education.”

That is not to say that Mayers, Richards, and Webber (teachers of sociology, Christian education, and theology, respectively, at Wheaton College) have nothing important to say. Webber’s section on the historical development of two alternative world views, stemming from the Renaissance and the Reformation, is succinct, accurate, and helpful. Mayer’s discussion of the emerging educational pattern as event-focused, noncrisis, holistic, goal-oriented, vulnerable, and non-sequential is informative.

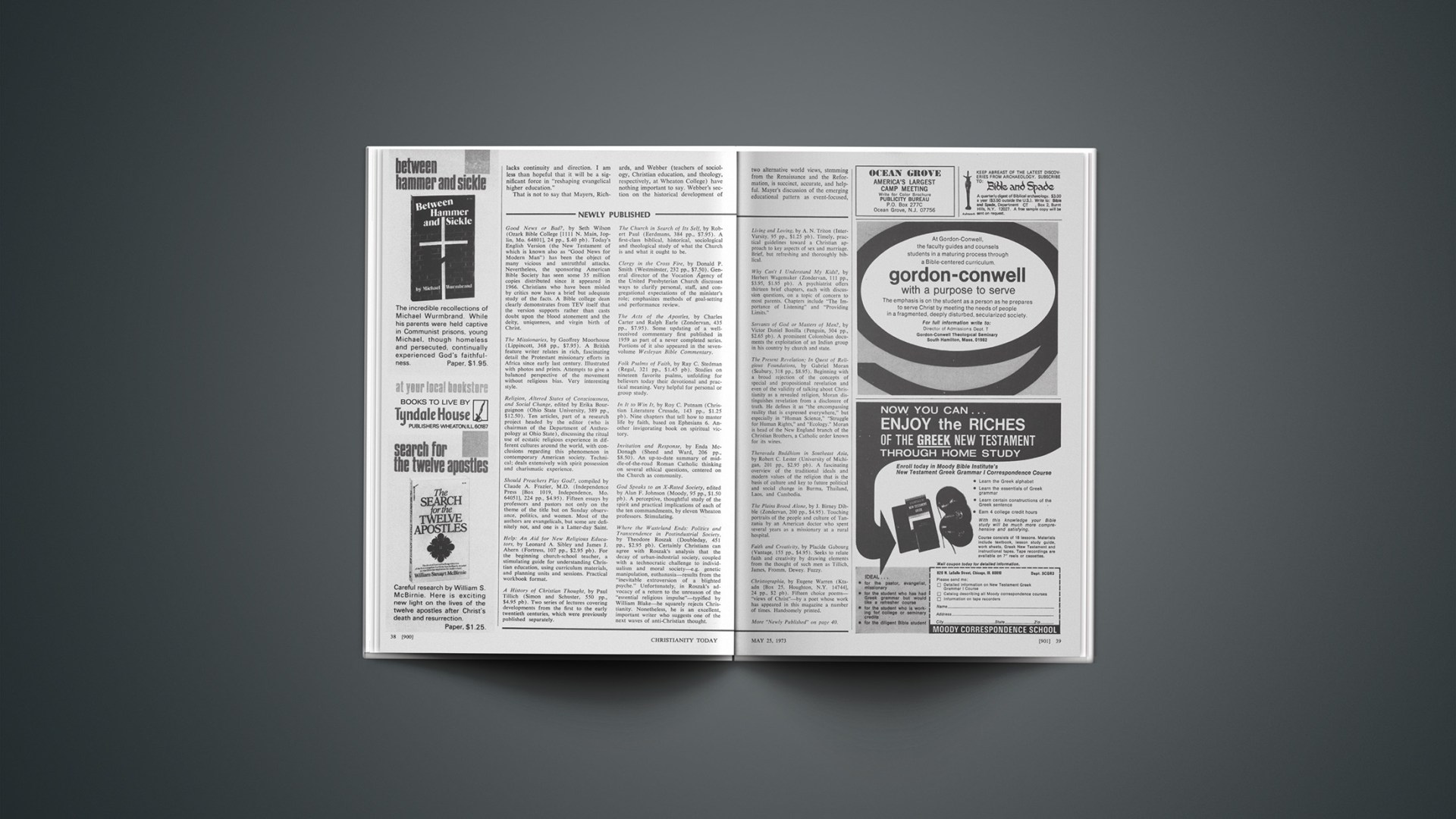

Newly Published

Good News or Bad?, by Seth Wilson (Ozark Bible College [1111 N. Main, Joplin, Mo. 64801], 24 pp., $.40 pb). Today’s English Version (the New Testament of which is known also as “Good News for Modern Man”) has been the object of many vicious and untruthful attacks. Nevertheless, the sponsoring American Bible Society has seen some 35 million copies distributed since it appeared in 1966. Christians who have been misled by critics now have a brief but adequate study of the facts. A Bible college dean clearly demonstrates from TEV itself that the version supports rather than casts doubt upon the blood atonement and the deity, uniqueness, and virgin birth of Christ.

The Missionaries, by Geoffrey Moorhouse (Lippincott, 368 pp., $7.95). A British feature writer relates in rich, fascinating detail the Protestant missionary efforts in Africa since early last century. Illustrated with photos and prints. Attempts to give a balanced perspective of the movement without religious bias. Very interesting style.

Religion, Altered States of Consciousness, and Social Change, edited by Erika Bourguignon (Ohio State University, 389 pp., $12.50). Ten articles, part of a research project headed by the editor (who is chairman of the Department of Anthropology at Ohio State), discussing the ritual use of ecstatic religious experience in different cultures around the world, with conclusions regarding this phenomenon in contemporary American society. Technical; deals extensively with spirit possession and charismatic experience.

Should Preachers Play God?, compiled by Claude A. Frazier, M.D. (Independence Press [Box 1019, Independence, Mo. 64051], 224 pp., $4.95). Fifteen essays by professors and pastors not only on the theme of the title but on Sunday observance, politics, and women. Most of the authors are evangelicals, but some are definitely not, and one is a Latter-day Saint.

Help: An Aid for New Religious Educators, by Leonard A. Sibley and James J. Ahern (Fortress, 107 pp., $2.95 pb). For the beginning church-school teacher, a stimulating guide for understanding Christian education, using curriculum materials, and planning units and sessions. Practical workbook format.

A History of Christian Thought, by Paul Tillich (Simon and Schuster, 550 pp., $4.95 pb). Two series of lectures covering developments from the first to the early twentieth centuries, which were previously published separately.

The Church in Search of Its Self, by Robert Paul (Eerdmans, 384 pp., $7.95). A first-class biblical, historical, sociological and theological study of what the Church is and what it ought to be.

Clergy in the Cross Fire, by Donald P. Smith (Westminster, 232 pp., $7.50). General director of the Vocation Agency of the United Presbyterian Church discusses ways to clarify personal, staff, and congregational expectations of the minister’s role; emphasizes methods of goal-setting and performance review.

The Acts of the Apostles, by Charles Carter and Ralph Earle (Zondervan, 435 pp., $7.95). Some updating of a well-received commentary first published in 1959 as part of a never completed series. Portions of it also appeared in the seven-volume Wesleyan Bible Commentary.

Folk Psalms of Faith, by Ray C. Stedman (Regal, 321 pp., $1.45 pb). Studies on nineteen favorite psalms, unfolding for believers today their devotional and practical meaning. Very helpful for personal or group study.

In It to Win It, by Roy C. Putnam (Christian Literature Crusade, 143 pp., $1.25 pb). Nine chapters that tell how to master life by faith, based on Ephesians 6. Another invigorating book on spiritual victory.

Invitation and Response, by Enda McDonagh (Sheed and Ward, 206 pp., $8.50). An up-to-date summary of middle-of-the-road Roman Catholic thinking on several ethical questions, centered on the Church as community.

God Speaks to an X-Rated Society, edited by Alan F. Johnson (Moody, 95 pp., $1.50 pb). A perceptive, thoughtful study of the spirit and practical implications of each of the ten commandments, by eleven Wheaton professors. Stimulating.

Where the Wasteland Ends: Politics and Transcendence in Postindustrial Society, by Theodore Roszak (Doubleday, 451 pp., $2.95 pb). Certainly Christians can agree with Roszak’s analysis that the decay of urban-industrial society, coupled with a technocratic challenge to individualism and moral society—e.g. genetic manipulation, euthanasia—results from the “inevitable extroversion of a blighted psyche.” Unfortunately, in Roszak’s advocacy of a return to the unreason of the “essential religious impulse”—typified by William Blake—he squarely rejects Christianity. Nonetheless, he is an excellent, important writer who suggests one of the next waves of anti-Christian thought.

Living and Loving, by A. N. Triton (Inter-Varsity, 95 pp., $1.25 pb). Timely, practical guidelines toward a Christian approach to key aspects of sex and marriage. Brief, but refreshing and thoroughly biblical.

Why Can’t I Understand My Kids?, by Herbert Wagemaker (Zondervan, 111 pp., $3.95, $1.95 pb). A psychiatrist offers thirteen brief chapters, each with discussion questions, on a topic of concern to most parents. Chapters include “The Importance of Listening” and “Providing Limits.”

Servants of God or Masters of Men?, by Victor Daniel Bonilla (Penguin, 304 pp., $2.65 pb). A prominent Colombian documents the exploitation of an Indian group in his country by church and state.

The Present Revelation: In Quest of Religious Foundations, by Gabriel Moran (Seabury, 318 pp., $8.95). Beginning with a broad rejection of the concepts of special and propositional revelation and even of the validity of talking about Christianity as a revealed religion, Moran distinguishes revelation from a disclosure of truth. He defines it as “the encompassing reality that is expressed everywhere,” but especially in “Human Science,” “Struggle for Human Rights,” and “Ecology.” Moran is head of the New England branch of the Christian Brothers, a Catholic order known for its wines.

Theravada Buddhism in Southeast Asia, by Robert C. Lester (University of Michigan, 201 pp., $2.95 pb). A fascinating overview of the traditional ideals and modern values of the religion that is the basis of culture and key to future political and social change in Burma, Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia.

The Plains Brood Alone, by J. Birney Dibble (Zondervan, 200 pp., $4.95). Touching portraits of the people and culture of Tanzania by an American doctor who spent several years as a missionary at a rural hospital.

Faith and Creativity, by Placide Gabourg (Vantage, 155 pp., $4.95). Seeks to relate faith and creativity by drawing elements from the thought of such men as Tillich, James, Fromm, Dewey. Fuzzy.

Christographia, by Eugene Warren (Ktaadn [Box 25, Houghton, N.Y. 14744], 24 pp., $2 pb). Fifteen choice poems—“views of Christ”—by a poet whose work has appeared in this magazine a number of times. Handsomely printed.

You’re in Charge, by Cecil G. Osborne (Word, 154 pp., $4.95). Paul Tournier’s warm introduction provides an appetizer for the reading of this sympathetic treatment of man’s responsibility for his actions. Lacks clarity in places. The author is a leader in the Yokefellows Movement.

Abiding in Christ, by James E. Rosscup (Zondervan, 254 pp., $5.95). A Bible professor at Talbot Seminary discusses the meaning of John 15 in light of other passages and sound biblical scholarship; deals with interpretations of the text that deny the believer’s security in Christ. Thorough, good material for Bible studies.

The City of the Gods, by John Dunne (Macmillan, 243 pp., $2.95 pb.). Reprint of an interesting, highly readable study of the characteristic forms and solutions that the problem of death has taken in various epochs, from the earliest times to the present. Less than adequate understanding of the Resurrection.

The Life of Jesus Critically Examined, by David Friedrich Strauss (Fortress, 812 pp., $12 pb). A fanciful but influential nineteenth-century study. It reportedly turned the young Marx away from Christianity. Edited by Peter Hodgson.

The Death of Christ, by Norman Douty (Reiner [Swengel, Pa. 17880], 120 pp., $3.95). A learned essay by a Calvinist who argues that Christ did not die only for the elect, thus attempting to knock limited atonement out of its high place among latter-day Calvinists. Well presented.

Contemporary American Protestant Thought: 1900–1970, edited by William R. Miller (Bobbs-Merrill, 567 pp., n.p., pb). The editor admittedly made his selections for this anthology with no attempt “to allot equal time to each conceivable claimant”; he includes only what he deemed “major creative contributions to the ongoing stream of development.” Hence the book is gravely mistitled. Fosdick, the Niebuhrs, and Altizer may be “creative,” but are they “Protestant”? The compendium offers a good way of seeing how men wander aimlessly when they no longer find Paul—and Luther, Calvin, and Wesley—“relevant.” Now the publishers owe us a volume of Machen, Mullins, Montgomery, and the like.

“… And the Criminals With Him …” Luke 23:33, edited by Will D. Campbell and James Y. Holloway (Paulist, 151 pp., $1.25 pb). Prisoners’ reflections on faith, society, and prison life with an article by the editors on the good news from Christ to prisoners. Realistic.

Using the Bible in Groups, by Paul D. Gehris (Judson, 47 pp., $1.25 pb). Four workshop sessions for group leaders that experiment in study methods to help others discover the uniqueness, authority, and meaning of the Bible today.

JESUS—Everything Jesus Christ Said and Did, Blended Into a Single Narrative in Modern English, compiled by Charles B. Templeton et al. (McClelland and Stewart [Toronto], 222 pp., $6.95). Former Youth for Christ leader and Canadian evangelist Charles B. Templeton, now a self-confessed agnostic, compiles a synthesis of the four Gospels in a modern paraphrase. Paradoxically, the volume is first-rate! Assisted by four able scholars and communicators, Templeton has come up with an easy-reading, biblically accurate, powerful presentation of the Christ-story. But—a life of Christ by an agnostic? Templeton’s explanation: “A pacifist may write a biography of Napoleon. My reverence for Jesus Christ is as high as it has ever been. But I have not returned to faith. I haven’t changed one iota.”

The Day Music Died, by Bob Larson (Creation House, 213 pp., $2.75 pb). Larson strikes again. With ignorance of music in general and prejudice against rock in particular, he begs young people to forsake their culture and turn to Christ. His definition of rock could also apply to Bach, Rachmaninoff, or Prokofiev. The reaction of young people to their music probably parallels that of most music lovers; music lifts the listener out of himself. The problem with Larson is that he assumes rock music (not just the lyrics) is inherently evil. One could carry his reasoning to the conclusion that all music is of the devil.

Experimental Preaching, by John Killinger (Abingdon, 175 pp., $3.95). Twenty-one sermons edited by the professor of preaching at Vanderbilt showing how to use such things as poetry, drama, and lighting effects as preaching aids. Unfortunately, some are weak in biblical content.

Private Money and Public Service: The Role of Foundations in American Society, by Merrimon Cuninggim (McGraw-Hill, 267 pp., $7.95). The president of the Danforth Foundation responds to frequent criticisms of such institutions. For those who deal with foundations, valuable as an insight into their future.

Heralds of God and A Faith to Proclaim, both by James S. Stewart (Baker, 222 and 160 pp., $1.95 each pb). Reprints of lectures on effective methods of preaching and, as a sequel, on five key doctrines that the preacher should proclaim. By the well-known Scottish preacher.

As a whole, however, the book lacks consistency and any sense of compelling logic. It includes a considerable amount of material that is beside the point. The Philippine case study is not used to its full advantage as an illustration of crosscultural education. Richards’s chapter on “Reshaping Church Education” contributes more to the bulk of the book than to an understanding of higher education (as the term is normally used). The focus of section III is elementary and secondary education rather than higher education, as the title of the book promises.

The smaller book, About School, is a collection of “Essays by Scholars Investigating Christian Higher Education” (the subtitle). Tom Howard of Gordon College fearlessly declares that Christian colleges have a mandate to oppose liberal education as an open-ended, presuppositionless, relativistic, question-raising enterprise. This opposition is to take the form not of a retreat from the discipline but of a fundamental opposition of axioms. Anthropologist Clyde McCone, defining education as “the transmission of culture through the processes of social interaction,” (p. 42), concludes that, since culture is the human product of man’s usurping the place of God in his life and becoming the author of his own value system, the only way we can speak of Christian education is in the sense of education taking place within the Christian himself.

Bernard Ramm—who inevitably has something of importance to say—sketches the shifting profile of American education, warns of certain dangers that arise from these changes, and suggests how the Christian college can play an increasingly significant role in shaping the future. Ramm sees that any attempt to use the university as an agent of reform is a disguised totalitarianism that will destroy its very essence. An ideological foreclosure of options is diametrically opposed to the search for truth and leads to bondage, not freedom.

The Young Turks of the Peoples Christian Coalition, with Dennis MacDonald as their recording secretary, carp and sulk through a chapter called “The New Left Student Movement and the Christian Liberal Arts College.” Although provocative because of its quasi-radical stance, the chapter seems out of place in a book on education, primarily because so many questions—and ethical ones at that—are already decided. War is wrong, Christian colleges are hothouses (they are “unjustifiable” and “an expensive cancer to the Body of Christ”), Campus Crusade is irrelevant, and so on. One gathers the impression that instant intellectual and moral superiority is granted to all who bolt the Establishment and fly the banner of the evangelical counterculture. When it comes to pretension, the mentality of this essay establishes a model for emulation.

In the other three essays, Augsburger discusses education and a Christian world view, while Reist and Woolsey write with Houghton College front and center in their thinking. These are not the best chapters in the book.

Hopefully, the Houghton essays will provoke lively discussion among evangelical educators whose concern for academic excellence compels them to tangle with the fundamental issues of our day.

Exciting Compendium

Crucial Issues in Missions Tomorrow, edited by Donald A. McGavran (Moody 1972, 272 pp., $4.95), is reviewed by Robert Brow, Anglican rector of Millbrook, Ontario.

This well-known missiologist’s compendium is missions reading at its best. An exciting introduction by McGavran pitches us into the radically new missionary situation of the past ten years. Arthur Glasser and Peter Beyerhaus give us a pungent contrast between some views of mission current in the ecumenical movement and those based on the New Testament. Alan Tippett’s “The Holy Spirit and Responsive Populations” should be read by every preacher, missionary, elder, and mission executive. Louis King’s “The New Shape” reveals the great gulf between ecumenical ideas and the very large number of evangelical missionaries. Another article by Tippett explains why so many millions of animists have responded to effective preaching. I hope that John Mbiti, writing on “Christianity and Traditional Religions in Africa,” will be followed by many other African theologians—he mentions 100 million Christians already, and David Barrett has calculated there will be 350 million Christians in Africa by A.D. 2000.

Paying due heed to “Quality or Quantity” by Ralph Winter would force many of our successful churches to ask whether they are in fact growing. George Peters makes a very impressive case for “Great Campaign Evangelism.” (This article, incidentally, is full of live examples, which I missed in his major work.) Two final articles by Roger Greenway and Edward Murphy remind us that huge cities are ripe fields for church growth if missionaries know what to do there.

In short, the book is a gem, and I enjoyed every facet of it.

—IN THE JOURNALS—

A useful aid for those who are seriously interested in China is China Briefing, a monthly, four-page newsletter sponsored by World Vision and available from the Asia Information Office, Room 711, Melbourne Plaza, 33, Queen’s Road Central, Hong Kong.