RICHARD W. GRAY, 68, former moderator of the 25,000-member Reformed Presbyterian Church, Evangelical Synod, a leader in church-planting and Christian counseling efforts in his denomination since its formation in 1965; February 28, in Coventry, Connecticut, of a heart attack.

ARASTOO SAYYAH SINA, Iranian pastor of St. Simon the Episcopal Church in Shiraz, an evangelical with a widespread ministry to young people and Muslims; February 19, in Shiraz, fatally stabbed by unknown assailants during violence following the takeover by the Khomeini regime.

JEAN VILLOT, 73, French cardinal and Vatican secretary of state; one of the few non-Italians ever to hold the post, which ranks second in the Roman Catholic hierarchy, he temporarily led the church after the deaths of Pope Paul VI and Pope John Paul I; March 9, in Vatican City, of heart and kidney ailments.

Sociologist Robert N. Bellah in his lecture “Civil Religion in America,” given to the Daedalus Conference on American Religion in May, 1966 (published Daedalus, Winter, 1967), made the subject popular. Bellah provided not only the vocabulary, but also the analytical tools with which to investigate civil religion.

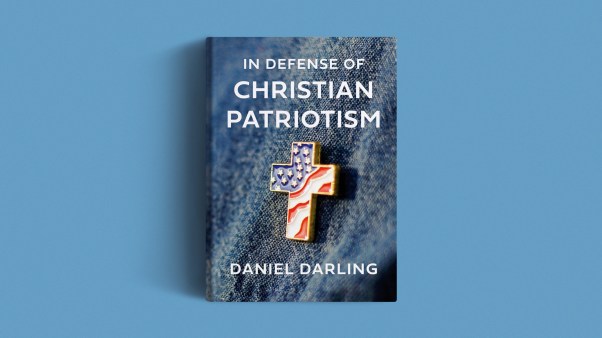

The term “civil religion” has not been precisely defined. Laymen cannot always know whether it is being advocated or criticized. I intend to clarify its meaning and criticize it from an evangelical stance.

The term “civil religion” usually means a folk religion held by a provincially minded group. In the current discussion, it is usually limited to the American religious scene.

Many people think that civil religion equates the status quo and the good of the country with God’s will. Such a “religion” would be just a patriotic assertion of the unqualified favor of God toward your own political group.

No doubt there is reason to think this is a typical American attitude. Lecturers, clergymen, and even presidents have conveyed this impression. Quite possibly, over-enthusiasm on public occasions has produced these statements.

Some critics decry any reference to God in public utterances, and, even further, any remarks complimentary of the American nation. Others are suspicious of any use of group symbolism to portray a sophisticated society. The first of these criticisms reflects the cynicism of liberal chic, the second shallow sociology.

Sidney E. Mead observes that “the being of a nation with a distinct identity implies a tacitly accepted ‘creed’ among its people” (American Civil Religion, Harper & Row, Richey and Jones, editors). If this is correct, then the appeal to national symbols is not in itself evil. The error creeps in when these symbols are divinized.

We must remember that the American nation struggled for identity in a period following the fragmentation of European religious life. It has no single integrating motif. Rather it had to deal with such “New Israel” expressions as “righteous Commonwealth,” “holy experiment,” “religious freedom,” “religious pluralism,” and “manifest destiny.”

A new perception of nationhood emerged that brought order to these varied motifs. The founding fathers tried to relate the Christian faith to the developing political order. And they used such Enlightenment concepts as “the laws of nature and nature’s God,” “higher law,” and “inalienable rights” in doing so.

In this process, religion and government overlapped, and this has never been obliterated. It is too much to expect the average person to appreciate either the complexity of the problem or the synthesis that has been achieved.

The tragic times through which our nation has passed, especially since 1917, have driven us to search for a set of symbols by which to reclaim our identity and self-worth. Has this quest deified “the American way of life” or “the nation under God”? A flat yes overstates the case.

Most of the critiques of civil religion come from the liberal wing of the church. The critics seem to think that the problem originates in Middle America. Here, they allege, laissez-faire is entrenched and institutionalized. They blame the mood of civil religion for opposing full employment and spending by the government to offer “services” to the whole of society.

Some deduce that the decrease of giving by the American church to international religious causes points to the predominance of civil religion. Martin E. Marty has written with heart-warming fairness in Part II of his bicentennial volume The Pro & Con Book of Religious America (Word). He blames American believers’ lack of concern for human need, especially abroad, on the wrong-headed policies of the mainline denominations. Then he adds a reservedly grateful note concerning the “faith mission” societies, whose strongholds and major sources of supply are in Middle America.

Two questions remain: Can the American religious public be indicted on a wide scale for assenting to a form of American civil religion? Further, what forms of public religious expression are legitimate and proper in our Republic? In other words, what measures may Christians properly use to affect the American scene?

Admittedly, printing “In God We Trust” on our coins or reading the Bible in public schools is not greatly influential. And it is unclear whether these practices violate the separation of church and state. It may tell us something when Christian ministers must go to a reformatory to read that which we dare not read in a public school.

Each day the United States Senate is led in prayer by its chaplain, Dr. Edward L. R. Elson. That reminds the body of its solemn obligation before God, and that “righteousness exalteth a nation, but sin is a reproach to any people.” Here is expressed in a high place, not civic, but prophetic religion.

Harold B. Kuhn is professor of philosophy of religion, Asbury Theological Seminary, Wilmore, Kentucky.