Anti-Zionism must not be dragged into the hyperbolic net of anti-Semitism.

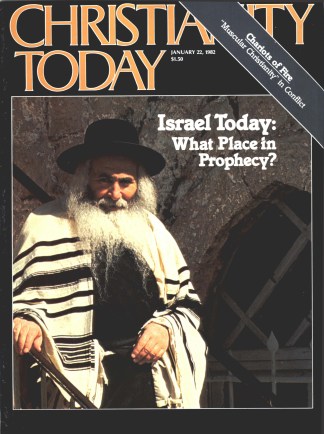

What should be the Christian’s attitude toward Israel?

This question is sparking a renewed debate among evangelicals. Adding fuel to the dispute is Jerry Falwell’s public and apparently unqualified support of Israel’s actions and his conspicuous identification with Menachem Begin. In early September, Falwell was shown on national telecasts meeting with the Israeli prime minister.

Although there is considerable anti-Semitism in the world—and it seems to be increasing—little progress can be made in our thinking about present-day Israel without recognizing that the charge of anti-Semitism can be overdone and turned into a bugbear that perverts our understanding and our sense of justice. Jingoists for Israel have made propagandistic hay out of the term on many occasions. Not infrequently Zionist supporters dub as “anti-Semitic” anyone who raises a question about Israel’s actions. Evangelicals (and fundamentalists) are not immune to this skewed perspective that virtually precludes the possibility of Israel’s culpability in any of its decisions.

The reasoning of such partisans is simple—and simplistic. Israel consists of Abraham’s descendants. God made a covenant with Abraham and his posterity (Gen. 12:1–3; 22:16–18). In it, he gave the land of Canaan to them in perpetuity. Moreover, God said he would bless those who bless the Abrahamic line and curse those who curse them. Thus, if one wants to believe the Bible and obtain God’s blessing, he ought to be a loyal, enthusiastic supporter of Israel. Israeli Jews, therefore, have the supreme right to the land of Palestine. Any action they take to defend or strengthen their hold on the land ought to be approved.

Although varying degrees of this bias favoring Israel can be found across the spectrum of evangelicals, dispensationalists are seen as that nation’s most ardent partisans. They interpret the establishment of the State of Israel as the major sign that we are in the last days before the Tribulation (Matt. 24:21) and the return of Christ to inaugurate his kingdom on earth (Matt. 24:29–30). The destruction of Israel would therefore mean for them the frustration of these prophetic expectations for the near future.

While I oppose anti-Semitism and the destruction of the State of Israel, I want to challenge the widespread use of the former term as a ploy to obscure questions of truth and justice concerning the Middle East situation. As a moderate dispensationalist (I maintain that there is a fundamental distinction between “Israel” and the church as two distinct but not unrelated peoples of God), I want to refute the notion that dispensationalism theologically requires a pro-Israeli stance. My focus on the Bible, however, should not be taken to imply that historical and psychological motives for supporting political Zionism have been unimportant in shaping the attitudes of both Christians and non-Christians.

Anti-Zionism

The term “anti-Semitism” is too broad to use in reference to either anti-Israeli sentiment or anti-Jewish prejudice. First of all, the Arab peoples are themselves Semitic, so it follows that when the shibboleth “anti-Semitism” is employed to squelch an impartial assessment of Israeli actions against Arabs, one is being anti-Semitic—that is, anti-Arab.

Second, propagandists for the State of Israel, from the time of Theodor Herzl and the first Zionist Congress in 1897, have tried to persuade the West that anti-Zionism is a species of anti-Semitism—that is, anti-Jewishness. That this equation is false is demonstrated in three ways. For centuries Arab societies accepted Jews as citizens and equals, some of them rising to positions of great influence. That relationship was undermined, however, by Zionist activity that sought to plant a new state in Palestine. This was contrary to the Balfour Declaration of 1917, which designated the area a “national homeland” for refugee Jews, and contrary to the wishes of the overwhelming majority of the people who lived in Palestine at the time. Jews owned about 6 percent of the land when the United Nations voted to partition Palestine, thereby making it possible for Zionists to create the State of Israel.

Furthermore, anti-Zionism cannot be equated with anti-Jewishness because a sizeable group of Orthodox Jews (e.g., the Neturei Karta) opposes the Zionist State of Israel for spiritual and theological reasons.

Finally, reflective and highly informed Jewish intellectuals like Alfred Lilienthal (see his recent volume, The Zionist Connection: What Price Peace?, Dodd, 1978) are adamantly opposed to the Zionist state of Israel on historical, legal, moral, and political grounds. None of these three groups is anti-Semitic (anti-Jewish), but all of them are anti-Zionist. Evangelicals need to understand this distinction and keep it before them as they assess the Middle East situation.

Dispensationalists are fond of quoting Genesis 12:3 to justify their partisan bias that favors Israel. Of all biblical interpreters, they are given to making distinctions in the text of Scripture and to emphasizing the limited application of its pre-epistolary sections. But they seem to have a blind spot here. Genesis 12:3 is not repeated in the New Testament. What do we find instead? The New Testament consistently teaches the principle of impartiality in our attitudes and actions toward all people (Matt. 5:43–48; Luke 6:28; Rom. 12:14).

The Epistle of James says that “if you show partiality, you commit sin, and are convicted by the law as transgressors” (2:9). No Christian should be anti-Semitic or anti any people. It is high time, therefore, for evangelicals to recognize that a blind and one-sided pro-Israeli partiality is a sinful attitude, for its flip side is the negative prejudice that views Arabs as less than full persons. Let us bless Jews, but if we want to be true Christians, let us also equally bless other people. It is our indifference to impartiality and distributive justice that robs us of God’s blessing far more than our neglect of Genesis 12:3.

If we want to bless Jews—indeed, if we want to bless anyone—the greatest thing we can do is to demonstrate to them the love of Christ so that they are attracted to the Savior who is the source of every blessing (Eph. 1:3). The pro-Israeli bias of evangelicals, however, has driven countless Arabs, Muslims, and other “Third World” peoples from the Savior.

We are not told in the New Testament to pray for the peace of Jerusalem. That is another Old Testament injunction (Ps. 122:6) that has been assimilated into a larger New Testament imperative. We are to pray for all men and for peace everywhere (1 Tim. 2:1–2). There will be no permanent peace in Jerusalem until Christ returns. In the meantime, we ought to be praying for peace in Berlin, Beirut, Belfast, Warsaw, and in every troubled city of the world in addition to Jerusalem.

Prophecy Need Not Mean Approval

Evangelicals, especially dispensationalists, fall into a major exegetical error when, in an effort to justify their bias, they turn to biblical passages that speak about Israel’s future. This mistake is threefold.

First, they misapply scriptural passages that prophesy a glorious future for Israel. Although I do not deny that Israel will have a special role in the messianic kingdom on earth, passages containing this reference should not be lifted out of context to buttress Israel’s contemporary claims. Some of the passages frequently misused in this way are Deuteronomy 30:3–5; Isaiah 11:11–12; 35:1, 2, 6–7; Jeremiah 23:3.

Second, it is often forgotten that the mere foretelling of an event by biblical writers does not necessarily carry the stamp of God’s approval on that event or its participants. Thus, even in scriptural passages that presuppose or imply the existence of an Israeli state in Palestine prior to the return of Christ to the earth (Ezek. 36–37; Zeph. 2:1; Matt. 24:15–21; Rev. 11:1–2), we are not to inject an added factor, namely, the assumption that such events are according to the directive will of God. After all, biblical prophets foretold the rise and activities of arrogant Gentile nations and wicked rulers (Dan. 2; 7; 8; 11; Hab. 1:6), unbelief in the Messiah (Isa. 53:1–3), and the coming of Antichrist (Dan. 11:36–45; 2 Thess. 2:8–9; Rev. 13). Although the crucifixion of the Messiah was foretold in the Old Testament (Ps. 22; Isa. 53; Dan. 9:26; Luke 24:25–27), that did not absolve his murderers of their guilt (Acts 2:23). And neither did God’s covenant promise to Jacob absolve him and Rebekah of the treachery they used to obtain the blessing (Gen. 27). Neither prediction nor promise provides grounds for exonerating all human acts related to its realization.

My dispensational perspective leads me to believe that there must be an Israeli state in the Middle East in order for certain end-time prophecies to be fulfilled (Dan. 9:27; Zech. 12:2–3; 13:8; 14:1–4; Matt. 24:15–20), but the existence of such a state does not carry with it a divine voucher any more than Jacob’s possession of the blessing he extracted from his father did.

In an effort to justify Zionist military action, some ask, “Didn’t Moses and Joshua use force to take the land of Canaan from the people who were inhabiting it at the time?” Of course; but have we forgotten a crucial difference? Divine revelation gave Moses and Joshua explicit instructions to go in and possess the land, executing capital punishment on debauched and impenitent peoples whose sin was a threat to the survival of the human race (Lev. 18:24–25).

Theodore Herzl did not have such revelation. Neither did Chaim Weizmann, nor David Ben-Gurion, nor Golda Meir, nor Menachem Begin. And all the evidence indicates that the Palestinian Arabs were not morally or spiritually worse than the Jews who occupied their land by illegal immigration and acts of terroristic violence (as committed by the Irgun and Stern Gang, for example). To be sure, history records atrocities perpetuated by both Jews and Arabs in the course of the long conflict that began shortly after 1917.

Who Are The People Of God Today?

Third, end-time prophecies pertaining to Israel are misconstrued when biblical teaching about “the remnant” is ignored. From the time of Israel’s exodus from Egypt, the nation was a mixed multitude. Even though God dealt with the people as a sociopolitical-religious entity, they apostatized again and again (Exod. 32; Judges; 1 Kings 18; Isa. 1:9; 6:13; 29:13–14). The Scriptures indicate that during the Tribulation period, two-thirds of the Jews living in Palestine will perish (Zech. 13:8). Those who survive will not all belong to the believing remnant, for at the inauguration of the messianic kingdom, unredeemed Jews and Gentiles will be removed from the earth by divine judgment (Ezek. 20:33–44; Matt. 8:11–12; 13:41–43). Thus, a redeemed remnant of Jews will constitute the nucleus of a new nation of Israel in the kingdom age (Isa. 60:21–22).

Israel today is not the people of God, nor should that nation be confused with the redeemed nation that will emerge from a small remnant during the messianic kingdom. Perhaps no nation in the world today is more opposed to the Christian faith and its missionaries. A Christian Hebrew is such an anomaly in the eyes of the State of Israel that he or she is not recognized as a bona fide Jew.

Biblically, when a Jew becomes a believer in Christ he becomes a member of the body of Christ, in which there is neither Jew nor Gentile (Rom. 11:1–5; Gal. 3:28). And in the future, it will only be believing Gentiles and true Jews—those who trust in Jesus as Messiah and Savior—who will enter the kingdom: “If the Lord is pleased with us, then he will bring us into this land, and give it to us …” (Num. 14:8; Rom. 9:4–8; 10:21; 11:25–27).

Who are the people of God today? Not Israelis or Jews or Gentiles, but regenerated believers in the gospel of Christ (1 Cor. 15:1–4; Rom. 1:16; 1 Pet. 2:9–10). We must not forget either the many thousands of Arab Christians who are part of the body of Christ and so related to us by a spiritual bond that can never be matched by the historical ties of Israel to the West and the church.

When I am asked whose side I am on in the Middle East conflict, I find myself questioning the questioner: Do you think there are only two sides—the Arab and the Israeli sides? In actuality, a diversity of positions exists among both Arabs and Israelis concerning claims and counterclaims in the Middle East. The only proper answer for the Christian is: I am on neither the Arab side nor the Israeli side, but I am seeking to be on God’s side.

How does a person determine what that is? By interpreting and applying the Scriptures with great care and integrity. As I seek to do this, I find that biblically the demands of truth, justice, and compassion take precedence over preferential treatment for any group of people, Jews not excepted (Prov. 21:3; Isa. 59:14; Jer. 23:5).

If we want to see Israel blessed, then let it and us abide by the words the Lord enjoined on Abraham: “… to keep the way of the Lord by doing righteousness and justice, in order that the Lord may bring upon Abraham what he has spoken about him” (Gen. 18:19). As we relate to Arabs and Israelis and seek to evaluate the ongoing Middle East crisis, “let us do good to all men” (Gal. 6:10), equally and compassionately in the name of Christ, for his throne will be established and maintained with “justice and righteousness … forever” (Isa. 9:7).

Mark M. Hanna is associate professor of philosophy of religion at Talbot Theological seminary in La Mirada, California. He is also director of evangelism and teachig for International Students, Incorporated.