NEWS

But recorded votes on the Senate floor may provide potent ammunition in next month’s elections.

For nearly a month, the U.S. Senate was tied up with the top two “social issues,” which had been heating to a boil ever since the Ronald Reagan election raised the vision and the energies of the country’s religious conservatives. But Senator Jesse Helms’s (R-N.C.) antiabortion legislation went down one vote short in mid-September, followed by his bill to bar the federal courts from ruling on prayer in public schools. Both fell victim to liberal-led filibusters.

Politically, the more significant defeat was the antiabortion bill, if only because the lobbying bloc for it has been vocal and growing in strength. Many religious leaders and organizations are at odds over the issue of school prayer.

What the legislative loss means for the right-to-life movement is unclear, although a rekindling of months-old bickering about strategy appears unavoidable. Both major pieces of prolife legislation, Helms’s bill and Senator Orrin Hatch’s constitutional amendment approach, could be debated again next spring. Hatch has been promised consideration by Senate Majority Leader Howard Baker. The future of Helms’s bill is less clear. Hatch withdrew his bill from the Senate-floor fray last month because of scant support and because he needed to focus on a tough reelection fight back home in Utah.

The two approaches are completely different, based on conflicting approaches. Hatch’s proposed amendment would permit state legislatures and Congress to enact laws restricting or prohibiting abortion. Supporters, including the National Right to Life Committee (NRLC) and the National Conference of Catholic Bishops, view it as a first step toward an amendment banning all abortions, except to save the mother’s life.

This approach sidesteps the questions of an unborn child’s “personhood” and focuses instead on the rights of states.

Senator Helms’s bill would not amend the Constitution, but would permanently prohibit federal funding of abortion and state that the unborn are human beings from the time of conception. This “finding” would have no force of law, but it is intended to encourage court challenges to abortion providers, leading eventually to a Supreme Court review of its 1973 Roe v. Wade decision legalizing abortion. An evangelical prolife group, Christian Action Council, favors this approach and actively opposes Hatch. NRLC, along with most multi-interest groups such as Moral Majority, officially supports both.

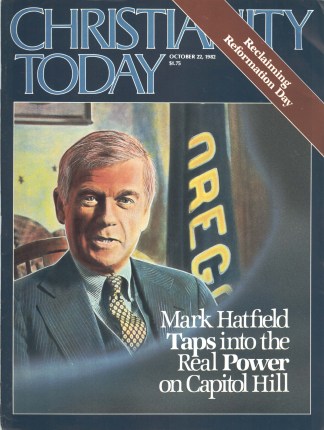

One senator who is solidly prolife is Oregon Republican Mark Hatfield. But he was not in the trenches with Helms last month.

Few senators have exasperated abortion lobbyists on both sides of the issue to the extent Hatfield has. What frustrates interest groups is that the standard litmus tests are meaningless on Hatfield. Neither his evangelical Baptist faith nor his Republican party loyalty causes him to conform to any set of ready-made positions.

Hatfield’s support for Helms’s prolife legislation was lukewarm at best, because of a clash between the two, as well as Hatfield’s longstanding reservations about the wording and intent of both Helms’s bill and Hatch’s proposed constitutional amendment.

Going on record for the right to life, Hatfield introduced his own bill last spring, to permanently prohibit federal funding of abortion except to save the mother’s life. When time ran short in August, Helms decided a parliamentary maneuver to force debate was necessary, and he attached a new prolife measure to the Senate’s national debt ceiling bill, prompting the filibuster.

Cries of “bill-rustling” went up from Hatfield’s staff, since the Helms amendment was virtually identical to Hatfield’s funding bill. Helms deepened the rift by attaching prayer-in-schools language to the bill as well.

The two senators met on several occasions and could not agree on a cosponsored amendment—a coup that might have placed prolifers in a practically defeat-proof posture. Part of the problem is a clash of personalities, since the two have a history of incompatibility.

Hatfield also has his doubts about the effects of the two major proposals. He never favored Hatch because he believed it would “Balkanize” the issue, with some states providing unrestrained access to abortion while others ban it entirely.

He also objected to the Helms Human Life Bill, viewing it as a slap in the face of the Supreme Court because it states that the court “erred” in its 1973 Roe v. Wade decision to legalize abortion.

Helms counters by saying it simply restores a proper balance between these two arms of government. The Supreme Court overstepped its bounds in 1973, Helms believes, and it is the duty of Congress to correct this.

Some viewed Hatfield’s equivocation on these measures as proof that proabortionists “got to him,” and they turned the pressure on full throttle. An article in the National Catholic Register detailed how Hatfield “gave Planned Parenthood what it wanted” by referring his own prolife bill to committee, effectively killing it.

Curtis Young, director of Christian Action Council, fanned the flames by mailing the article to a dozen Oregon evangelical leaders. Young criticized Hatfield for remaining aloof from “our one shot to dramatically shift the national perception of abortion.”

Pressure also came from President Reagan, who telephoned Hatfield as part of his last-minute blitz in support of Helms. The National Right to Life Committee and the National Association of Evangelicals both supplied letters urging his support.

On the other side, Oregon activists of a more liberal bent, who respect Hatfield for opposing military spending and favoring the Equal Rights Amendment, tried their best to pull him into their camp. Their vigorous efforts caught prolifers there by surprise. “They took him to task with full-page newspaper ads, letters, and phone calls,” said Rita Radich, an attorney who is president of Oregon’s Right to Life chapter.

Instead of accusing him of being swayed by proabortionists, Oregon’s prolifers maintained their support in spite of a good deal of confusion. “He’s not an easy person to understand or to read,” Radich concluded.

A telling blow to Helms’s school prayer legislation seemed to be that it was perceived as an attack on the federal courts. The bill would have kept the federal courts from overturning state laws permitting voluntary prayer in the schools, which the Supreme Court banned in 1962. There also appeared to be some resentment against Helms personally for his insistence on recorded votes on the Senate floor. By putting senators clearly on record, prolife and school prayer lobbies have valuable tools for use in this fall’s reelection campaigns against those who voted the wrong way.

During the thick of the school prayer fight, Hatfield introduced a bill that approaches school prayer from a less volatile perspective. His bill would allow public secondary school students to meet voluntarily for religious purposes, just as they meet for a variety of other extracurricular activities. The bill is based on a recent Supreme Court decision, Widmar v. Vincent, which said college students could meet for religious purposes on campus if the college generally makes facilities available to student groups for nonreligious activities. The advantages of his bill, according to Hatfield, are that it does not deny jurisdiction to the courts, does not force students to pray, does not permit school officials to influence the form of prayer, and it doesn’t interfere with President Reagan’s proposed constitutional amendment permitting voluntary prayer in schools.

It was indeed a black September for the prolifers and school prayer lobbyists. In the words of one prolife newsletter, “… after almost two full years of grinding work (it was) a final crushing of hopes.…” But the number of citizens who are becoming sensitized to the “social issues” seems to be growing, not diminishing, and their standard bearers in Congress seem to be full of fight still. There is every reason to believe the battle will be joined again when the new Congress is seated next year.

Reformed Alliance Suspends South African Church

The Dutch Reformed Church of South Africa has been suspended from membership in the one organization it really cared about: the World Alliance of Reformed Churches (WARC). Meeting in Ottawa, Ontario, the alliance effectively ousted both the major white church with close government ties, the NGK (for Nederduitse Gereformeerde Kerk), and the smaller white denomination, the NHK (for Nederduitse Hervormde Kerk).

The action, just short of actual expulsion, means the two denominations are barred from voting and cannot hold office in the alliance. The WARC action to distance itself from the denominations who serve as apologists for apartheid (separate development), followed official condemnations of the policy in 1964, 1970, and 1977 that brought no visible results. The two suspensions were the first in the more than 100-year history of the alliance.

As correspondent Paul Van Slambrouck wrote recently from Johannesburg, the NGK “derives its clout in South Africa from the fact that it represents two-thirds of the dominant Afrikaners, including most of the government leaders. The church maintains considerable influence over government policies by endorsement or quiet acquiescence. The ruling National party, the secret political-cultural Broederbond, and the NGK church are mutually influential when it comes to establishing each group’s leadership and operative ideology.”

A substantial number of the 400 delegates to the conference came reluctant to support a summary suspension of South Africa’s white Reformed churches. But observers report that attitudes hardened as the NGK delegates themselves detailed how closely their church is involved with, and supportive of South Africa’s ruling National party. Careful questioning also revealed that, contrary to claims of being an “open” church (allowing nonwhite visitors), both groups practice segregation in worship, including communion. Only two delegates voted against suspension.

The resolution labeled apartheid as “an issue on which it is not possible to differ without seriously jeopardizing the integrity of our common confession as Reformed churches.” It called the moral and theological justification of apartheid “a travesty of the gospel, and in its persistent disobedience to the Word of God, a theological heresy.”

Separate development is, the document affirmed, a pseudo-religious ideology that 1) is based on a fundamental irreconcilability of human beings, thus rendering ineffective the reconciling and uniting power of our Lord Jesus Christ; 2) has led to exclusive privileges for the whites at the expense of the blacks; and 3) has created a situation of injustice, oppression, and “suffering to millions.”

Significantly, for the first time in more than 30 years in an international church meeting, the NGK’S two so-called daughter churches did not come to its defense. In the past, the NG Kerk in Africa (for blacks) and the NG Sending Kerk (for Coloreds of mixed race), while deploring apartheid, have pleaded that no action should be taken against the NGK and that it should be given more time. This time the daughter churches’ four delegates abstained from both speaking and voting.

Lifting of the suspension requires that three conditions be met. The white denominations must stop excluding black believers from church services and communion; they must reject apartheid in their synods and commit themselves to dismantling the system; and they must give concrete support to those suffering under apartheid.

Delegates of the NHK responded by proposing that it withdraw permanently from WARC. The NGK delegates will recommend that it continue in the alliance, but do not expect their advice to be taken.

In another action, which some delegates felt had an element of overkill, the alliance voted in as its new president Allan Boesak, a South African Colored theologian who is chairman of the two groups that have nudged the daughter churches into activism: the Fraternal Circle of Brothers (Broederkring) and the Alliance of Black Reformed Christians in South Africa.

Boesak had authored a conference study guide that asserted that “not only is South Africa the most blatantly racist country in the world, it is also the country where the church is most openly identified with the racism and oppression that exists in that society.”

But in his acceptance speech, the new president took a softer line. He called the expulsion a historic and awesome step. As a minister of the NGSK, he said he hoped the two white churches would accept the action in the same spirit in which it was taken. “We refuse to let these churches go and we hope they will seriously reconsider their stand.

Personalia

Kenneth Cain Kinghorn has been named vice president and provost of Asbury Theological Seminary (Wilmore, Kentucky). Kinghorn, presently a professor of church history at Asbury, will serve as the seminary’s chief academic officer and dean of the faculty.