What the experts say about strengths and weaknesses of the major new Bible versions.

With the appearance of two more Bible editions this past year, Christians are asking again, “What are the strengths of each?” To help guide readers through the forest of Bible translations and editions, CHRISTIANITY TODAYinterviewed a number of Bible scholars to discover how they evaluate the 11 major translations or editions of the Bible now available.

Twenty years ago when he was a young man studying for a doctorate, George Martin was challenged at a weekend retreat to read the Bible. He went to a local bookstore, thumbed through a number of translations, and chose the New Testament in Modern English by J. B. Phillips. “It caught my eye, I bought it, prayed that God would speak to me through it, and read it,” Martin says. Today George Martin is the editor of God Speaks Today, one of the largest daily devotional guides to Bible reading for Catholics.

Far more Bible translations line the bookstore shelves than when George Martin made his choice. Most of us need a more thorough guide to Bible translations than might have been necessary back then. Also, churches and Sunday schools need thoughtful recommendations to help them choose a Bible for church use.

When more translations appear, more Bibles are sold. In 1982 the Riverside Book and Bible House in Iowa Falls, Iowa, one of the nation’s largest Bible wholesalers, had more than $26 million in Bible sales. Sales manager Mike Anderson says, “Even in a depressed economy Bible sales have continued to increase, though volumes under $25 did better last year than more expensive editions.”

Such a demand suggests that different translations meet the needs of different people. A person who has never read the Bible before will not want the same translation as the seasoned Bible student who wants to know what the original Hebrew and Greek have to say. Some may find unappealing the rich cadences of a responsive reading from a translation that a well-educated evangelical congregation enjoys.

Of course, the “original Bible” was not a single document but a whole series, written over the centuries by many different authors. What we have today are copies of copies, some of them very close to the original manuscripts, but none of them from the hand of the original author. And translation is not a simple restatement of individual words from one language to another.

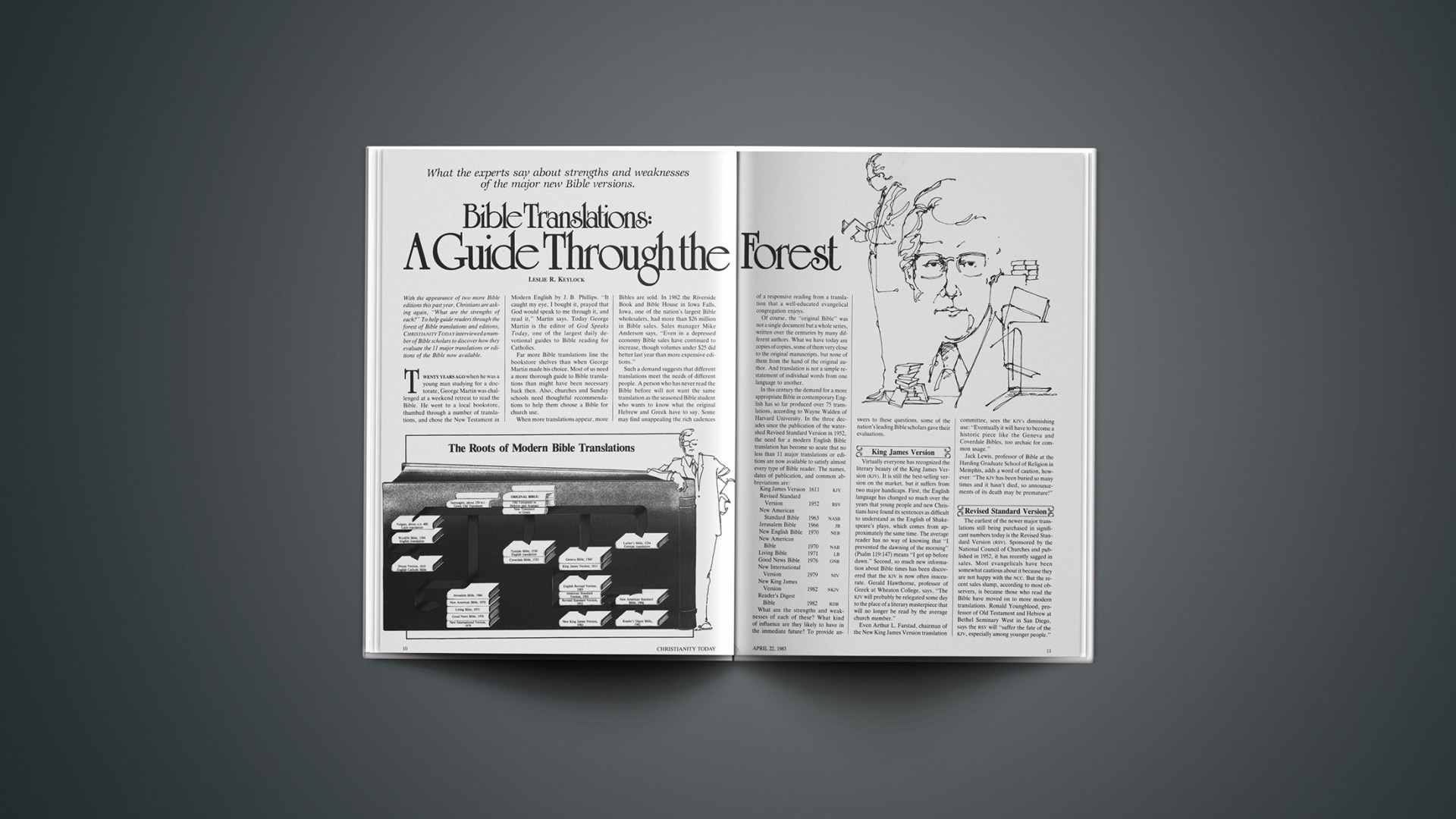

In this century the demand for a more appropriate Bible in contemporary English has so far produced over 75 translations, according to Wayne Walden of Harvard University. In the three decades since the publication of the watershed Revised Standard Version in 1952, the need for a modern English Bible translation has become so acute that no less than 11 major translations or editions are now available to satisfy almost every type of Bible reader. The names, dates of publication, and common abbreviations are:

What are the strengths and weaknesses of each of these? What kind of influence are they likely to have in the immediate future? To provide answers to these questions, some of the nation’s leading Bible scholars gave their evaluations.

King James Version

Virtually everyone has recognized the literary beauty of the King James Version (KJV). It is still the best-selling version on the market, but it suffers from two major handicaps. First, the English language has changed so much over the years that young people and new Christians have found its sentences as difficult to understand as the English of Shakespeare’s plays, which comes from approximately the same time. The average reader has no way of knowing that “I prevented the dawning of the morning” (Psalm 119:147) means “I got up before dawn.” Second, so much new information about Bible times has been discovered that the KJV is now often inaccurate. Gerald Hawthorne, professor of Greek at Wheaton College, says, “The KJV will probably be relegated some day to the place of a literary masterpiece that will no longer be read by the average church member.”

Even Arthur L. Farstad, chairman of the New King James Version translation committee, sees the KJV’s diminishing use: “Eventually it will have to become a historic piece like the Geneva and Coverdale Bibles, too archaic for common usage.”

Jack Lewis, professor of Bible at the Harding Graduate School of Religion in Memphis, adds a word of caution, however: “The KJV has been buried so many times and it hasn’t died, so announcements of its death may be premature!”

Revised Standard Version

The earliest of the newer major translations still being purchased in significant numbers today is the Revised Standard Version (RSV). Sponsored by the National Council of Churches and published in 1952, it has recently sagged in sales. Most evangelicals have been somewhat cautious about it because they are not happy with the NCC. But the recent sales slump, according to most observers, is because those who read the Bible have moved on to more modern translations. Ronald Youngblood, professor of Old Testament and Hebrew at Bethel Seminary West in San Diego, says the RSV will “suffer the fate of the KJV, especially among younger people.” The irony is that when the RSV first appeared, many Christians criticized it for being too modern!

Most scholars admire the accuracy of the RSV but feel it is now dated. Jack Lewis, for example, says, “I don’t find anything wrong with using it, but it is not written in current English.” Gordon D. Fee, professor of New Testament at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, emphasizes that its language reflects “a rich tradition that goes all the way back to Tyndale,” but he adds that its archaisms are the result of failing to take the “dynamic equivalence” approach to translation seriously enough. That approach suggests that a good Bible translation is not a word-for-word translation from Hebrew or Greek into another language, but rather a quest for a dynamic equivalent of the biblical ideas and concepts in a second language. “Let not your hearts be troubled” is no longer current English; a dynamic equivalent would be “Do not be worried and upset” (John 14:1, GNB).

Over 50 million copies of the RSV have sold to date, and Kenneth Barker, chairman of the New International Version translation committee, sees it as “continuing to enjoy mainline denominational support at the official level.” Donald A. Carson, professor of New Testament at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, adds that some people like it because its archaic resonance is associated in their minds with “holy language.”

Whether the proposed revision of the RSV will revive its career or whether it will hasten its demise remains to be seen. One task of the committee doing this revising is to attempt to eliminate what chairman Bruce Metzger, professor of New Testament language and literature at Princeton Theological Seminary, calls its “overmasculinization.” Some conservative Christians have reacted strongly against this change (CT, Feb. 18, p. 19), but evangelical scholars admit that sometimes masculine words have been used in English that do not occur in the Hebrew and Greek originals. For example, Psalm 143:2 says, “No man living is righteous before me,” but “man” does not occur in the original. (The NIV translates this, “No one living.…”) They respect the RSV for its scholarship but conclude that, in the words of Donald Carson, “It will have a future in non-conservative circles but not elsewhere.” Some evangelicals, such as Arthur Farstad, admit that the RSV New Testament was well done but argue that Jewish and liberal influences have given the Old Testament a bias. Metzger denies any theological bias, however, and insists that like the KJV after 1611 the RSV will gradually push its way uphill to “get accredited.”

Living Bible

The Living Bible (LB) is not really a translation. It was an attempt by one man to put the Bible into language his children could understand. Knowing neither Hebrew nor Greek, Kenneth L. Taylor, then editor of Chicago’s Moody Press and now president of Tyndale House Publishers, produced a highly popular, readable, contemporary interpretation that has, contrary to anyone’s expectations, sold well over 25 million copies. An example of Taylor’s contemporary touch is the description of Job as “the richest cattleman in that entire area” (Job 1:3).

Scholars agree that the LB has helped convert many non-Bible-reading Christians to Bible reading and has been an ideal first Bible for young people and family devotions.

But like any one-man translation it suffers from the limits of what one person can know, and lacks the checks and balances provided by a committee. (Amos 1:1 consists of a mere 12 words in Hebrew; the LB has 30.) Donald Carson notes that reading comprehension is no higher for the LB than for the New International Version, and adds that Taylor’s doctrinal views are visible in both the translations and the footnotes.

Taylor is continuously revising the LB, however, and a number of scholars believe it will be influential for many years.

New English Bible

The first British Bible to break completely with the King James tradition was the New English Bible (NEB). In an effort to produce a work that was both accurate and literary, the translation committee included both biblical scholars and men of letters. To date it has sold over 12 million copies.

Scholars have applauded the beauty of its English. Gerald Hawthorne, for example, praises it for “some marvelous phrases,” and calls it “a superior translation.” He adds, “It has incorporated the ideas of modern linguistics. And where the Hebrew text is incomprehensible, the translators have chosen to avoid nonsense by adopting meanings from the Septuagint and other cognate languages. Though many Christians frown on such a practice, I feel it is legitimate.”

But the NEB has nevertheless not done well in evangelical circles in America. Americans object that it is “too British,” but even the English have not welcomed it. Donald Carson objects that it is “so consciously aristocratic” and has “the bias of the Oxbridge intelligentsia.” Ronald Youngblood says, “Even people in England can’t understand it.” As a result, other translations are more popular even in the Church of England. Arthur Farstad says, “I understand whole warehouses are full of them and efforts have been made to force them on churches and factories in England.”

More serious is the charge that the NEB translators took undue liberties with the text. Jack Lewis objects to “too much rearranging” of the verses, and Gordon Fee protests that it contains “too many exegetical options that are the point of view of a small number of scholars, not proper for a translation.” In the NEB, 1 Corinthians 7:36, for instance, is made to refer to celibate marriage, though few scholars support that translation. Donald Carson dislikes the fact that “more than 100 textual displacements have been made in the Old Testament alone—without any textual basis!”

Metzger and Youngblood both mentioned that some of the idiosyncrasies of NEB translation committee chairman G. R. Driver have crept into the text by the sheer force of his personality.

A second edition of the NEB is expected in 1985, after a revision process of several years. “Many of Driver’s more objectionable opinions will be removed,” Metzger indicates. “Also, the British edition is going metric.”

The NEB has not caught on well. Whether the revisions will be radical enough to make it more acceptable remains to be seen.

Good News Bible

The Good News Bible (GNB, also called Today’s English Version) has already sold over 15 million copies, along with some 65 million New Testaments. Translated by Southern Baptist Robert Bratcher and sponsored by the American Bible Society, it is the first “dynamic equivalence” translation; that is, Bratcher and the committee of scholars who assisted him did not try to make a literal translation. Instead they asked, “What does the biblical text mean?” Then they tried to find the equivalent meaning in contemporary English. For example, the fourth beatitude reads, “Happy are those whose greatest desire is to do what God requires; God will satisfy them fully.”

The GNB has been widely used by the American Bible Society as a pattern for vernacular translations on the mission field. Kenneth Barker says, “The GNB is an outstanding example of the principles of dynamic equivalence.” Gerald Hawthorne adds that “the GNB is highly accurate,” though many evangelicals question the characteristic use of “death of Christ” in place of “blood of Christ.” The principles of dynamic equivalency were developed by evangelicals such as Eugene A. Nida and Kenneth L. Pike of the Wycliffe Bible Translators. Wycliffe stresses accuracy, not word-for-word translation.

How influential will the GNB be in the United States? Jack Lewis feels it has its place as a Bible with a simplified vocabulary and contemporary language, so it will continue to circulate widely.

Gordon Fee says, however, “As a pew Bible it is almost too idiomatic. But it is very, very good. As long as the American Bible Society continues to back it, it will have a future.”

Critics of the GNB note, however, that it has its faults. Newsweek said it is “useful for new readers, but short on poetry and majesty.” Of course, anyone who objects to the philosophy of dynamic equivalency will find the GNB “too free.” In addition, Catholic biblical scholar Mitchell Dahood says, “philologically, it is 30 years out of date.”

Observers have also noted that Bratcher’s abrasive reactions to his more conservative critics has hurt its acceptability and sales in evangelical circles.

Metzger points out, however, that “the GNB is the best translation for nonchurch people because of its readability,” though he admits “it is not a study Bible for church members.”

New American Standard Bible

Kenneth Barker divides modern translations into three types: literal, mediating, and free.

The most literal, word-for-word translation on the market today, everyone agrees, is the New American Standard Bible (NASB). A surprise best seller among studious Bible readers, it has already sold over 15 million copies, despite what many feel is its atrocious English—in Gordon Fee’s words, “English as it was never spoken by anyone!” For instance, Ephesians, 1:4–5 reads, “In love He predestined us to adoption as sons through Jesus Christ to himself, according to the kind intention of His will.…”

Donald Carson respects the scholars behind the NASB and feels the Old Testament is better than the New Testament. “But its literalness makes it a poor translation; its English is choppy and appalling.”

The NASB is a conscious attempt to revive the American Standard Version of 1901. Unfortunately, that translation never gained a wide audience and the NASB is likely to follow in its steps. Gerald Hawthorne opposed the idea of trying to revive the ASV from the very beginning and feels now that the NASB is often not as good because it is so wooden and literal. Bruce Metzger sees it as having “a rather limited appeal,” but argues, “We need it among the versions—though not in the pulpit.”

As Ronald Youngblood comments, however, “The NASB will probably remain the favorite of those looking for an ostensibly word-for-word translation, thinking it is much closer to the intent of the original author.”

New King James Version

In August 1982 Thomas Nelson Publishers completed what Newsweek called “the most expensive Bible project in history.” A team of 130 scholars worked on the New King James Version (NKJV), published at a cost of $4.5 million.

The NKJV stays close to the original KJV but replaces archaic words and phrases with contemporary parallels.

The purpose of the NKJV, as stated in the Preface, is to “maintain that lyrical quality which is so highly regarded in the Authorized Version” and preserve its form, precision, and devotional quality.

The updating of the KJV has been consciously conservative. The translators of the NKJV have retained words for ancient objects for which no modern substitutes exist, such as chariot and phylactery. They have also retained hallowed theological terms such as propitiation, justification, and sanctification.

But they have replaced thee, thou, ye, thy, and thine with You, Your, and Yours. All verbs ending in –eth and –est have been modernized. Subject headings have been put in italics, poetry is written as poetry, and modern punctuation marks have been introduced.

Much scholarly response to the NKJV has raised questions about it. Jack Lewis questioned the market for such a translation. “The die-hard KJV people won’t use it, and young people prefer to read the Bible in modern English.” (The publishers point out that die-hard KJV people and young people are using it.)

Fee and Metzger wonder about the wisdom and accuracy of the title. Metzger also objects to the capitalization of pronouns for deity. “Even the KJV doesn’t capitalize such pronouns.”

More serious, perhaps, is the charge that the NKJV didn’t make enough changes. Donald Carson says, “The NKJV isn’t modern enough, and is too awkward and heavy. It may be a halfway house for some KJV readers, but they will move on.”

The major objection these experts had to the NKJV, was its dependence on a textual tradition most scholars feel is outdated, the Textus Receptus or “Received Text” used by the translators of the KJV. They insist that the “eclectic” Greek text of ninteenth-century biblical scholars Westcott and Hort is closer to the original writings of the New Testament books. Kenneth Barker says, “The vast majority of textual critics, including most evangelicals, support the eclectic text.”

However, Arthur Farstad, chairman of the NKJV translation committee, rejects the suggestion that the KJV was based on late medieval manuscripts. “The KJV translators had more manuscripts than people realize. The best come from the fifth, sixth, and ninth centuries. Just because the manuscripts of the eclectic text come from the fourth century, they need not be better. I believe some fourth-century manuscripts supporting the Received Text will be found. For example, there are whole cartons of manuscripts at Saint Catherine’s monastery in the Sinai Peninsula that Kurt Aland, the leading German authority on the biblical text, was not allowed to photograph.”

Farstad is enthusiastic about the future of the NKJV. “Along with the NIV, it has a good chance of being one of the two top Bibles.”

Reader’S Digest Bible

In September 1982 after two years of planning and four years of production, the Reader’s Digest Bible (RDB) appeared. It claims to be the first condensation of the Bible. In its short life it has already been the subject of evangelical wrath and cartoon satire. (One such cartoon shows the editor tossing a coin and saying to his staff, “Okay, it’s settled then. Heads we’ll kill ‘Thou shalt not steal,’ or tails, ‘Thou shalt not commit adultery’!”)

To be fair, however, the RDB states that it was not intended for the person who is already reading the Bible, but for the person “who has little or no knowledge of the Bible, … the person who reads the Bible … only selectively, … young readers who have never read the Bible.” It was designed to supplement, not replace, the complete Bible.

To help such readers Bruce Metzger and the Bible scholars who worked with him condensed the RSV translation of the Bible from almost a million words to about 600,000. Over half a million copies of the RDB have already been sold.

Evangelical Bible scholars have been basically positive about the RDB. Jack Lewis says, “I don’t think the RDB people thought churchmen would go overboard for it. It’s not going to take the place of the other versions. But modern pagans might move from it to a more detailed Bible. Of course, everybody is unhappy with what is left out. But it should be treated like a children’s story Bible.”

Donald Carson agrees, with qualifications. “In a sense it will do in a milder way what the LB did: act as a hook to get people to read the Bible. But my question is why it was necessary with so many readable Bibles already on the market.”

Metzger sees the RDB as another way of reaching those who have neglected to read the Bible. “It is a kind of evangelistic tool to arouse some people alienated by the Bible’s length and complexity.”

The strongest criticism has been to the introductions to some of the books, which adopt critical views of the Bible, which most evangelicals strenuously oppose. Arthur Farstad, for example, says, “Initially I felt the RDB had some merit and would help some people. But the introductions alienated me completely; they are all slanted to liberal views. So now I wouldn’t give it to anyone on the planet! It’s a dangerous book for the uninformed.”

Jerusalem And New American Bibles

Among Catholics the Jerusalem Bible (JB) and the New American Bible (NAB) have replaced all earlier Bible translations. In the last decade the number of Catholics doing daily Bible study has greatly increased, and George Martin, editor of God’s Word Today, feels that both the JB and the NAB will have a future in Catholic circles. “They will continue to be used by the growing numbers of Catholics who are starting to do personal Bible reading and study,” he says.

Noted Catholic Bible scholar Daniel Harrington mentions that the JB has been criticized for its dependence on the French version and the NAB for its occasional clumsiness and inconsistencies. “The two translations complement each other, the NAB being the one usually read in public worship, the JB almost always smooth and readily understandable. Like the NIV, the NAB stands between the RSV and the GNB, while the JB is more like the NEB.”

Protestant reaction has varied from appreciative to ecstatic. Lutheran Bible scholar Frederick W. Danker says the NAB deserves, for the present, the designation “the American Bible.” Gordon Fee agrees: “Except for some Catholic idiosyncrasies, for me personally, it is the Bible, much better than the RSV.”

By contrast, Ronald Youngblood reacts similarly to the JB, though it annoys him at times. “The JB is a Bible I become alternately ecstatic and enraged about. Its phraseology is especially happy. But the notes are very opinionated and represent the liberal end of the spectrum.” Arthur Farstad also objects to the impact of older liberal Protestant views in the footnotes. “The JB has many fine literary touches, but the footnotes often cancel out what the text is saying.”

Both the JB and the NAB are being revised. The third edition of the French JB has already appeared, and English editions are expected to conform to it. For five years, the NAB has been under revision to remove what some scholars see as inconsistencies introduced by one of its final editors; there are also plans to shorten some of its lengthy sentences, and improve its sometimes uninspiring and pedestrian style.

New International Version

The translation that appears to be rapidly developing into the closest thing to a standard Bible among evangelical Bible-reading people in America is the New International Version (NIV). Almost every scholar consulted gave it enthusiastic applause.

Produced by a team of 115 scholars over a period of seven years at a cost of $2.25 million and published by the Zondervan Publishing House, it has gained the acceptance of a wide spectrum of readers. Over six million copies have already been sold. Its sales have been rapidly escalating since it appeared in 1978 and now rival those of the KJV. Richard Ostling of Time says the NIV “may be the Bible that finally breaks the King James hold on evangelical and fundamentalist Bible buyers.”

Most significantly, the NIV has been adopted as the Bible for use in church services in many circles. Gordon Fee thinks the NIV “is fast becoming the pew Bible of evangelicals, as the RSV has been for mainline denominations.” He places the NIV between the now-conservative RSV and the GNB. “The NIV doesn’t go beyond the GNB, but it is in the same ballpark. It is, however, more careful, more sensitive to evangelical shibboleths, and more open to traditional terminology.”

The NIV has already been officially approved by a number of evangelical denominations. A number of Sunday school publications are using it. The Navigators have adopted it for use in their Bible memorization programs. Even such mainline denominations as the Episcopal Church have liturgical commissions considering its official use. Kenneth Barker predicts that “the NIV will stand the test of time and will be one of the few current translations that will endure. I expect it will eventually enjoy the most widespread use among evangelicals, evangelical churches, and a significant number of nonevangelicals.”

Bruce Metzger also sees the NIV as the “standard” Bible of the future among evangelical Christians. He even feels the NIV “has it over the RSV” in contemporary language.

The NIV has also become part of the family devotions of many Christians. “In our family,” Donald Carson says, “we use the NIV all the time. I hope my five-year-old will treat it the way I treated the KJV. It has the best chance of capturing the support of the majority of English-speaking evangelicals worldwide over the next 50 years.” Gerald Hawthorne says, “The NIV is one of the very best translations in American English today for church services and personal study. It is close to the Hebrew and Greek text without being too literal. My wife, who grew up on the KJV, loves the NIV and says it is like reading the Bible for the first time.”

More conservative scholars such as Arthur Farstad also praise the NIV for its accomplishments, but they add reservations. “I agree that the NIV is beautifully done in a good English style. But I have a problem with its precision. Is it close enough to the original? For example, it leaves out connectives in some cases that change what the writer said. In 2 Peter 2:1 it leaves out the Greek connective and turns Peter’s long sentence into two crisp sentences. But it’s no longer what Peter said. The NIV does that far too often.”

Despite some criticism, no other modern translation has begun its journey so auspiciously. It would seem that we will see much more of the NIV in the years to come.

The Story Of Past Bible Translations

Before the invention of printing, Bibles and Bible portions were laboriously copied by hand. Translation is the difficult art of studying the numerous copies and trying to select the best way of translating into English the best form of the copies.

People differ on what is a good translation. Is it a literal translation from the original languages? Or is it a “dynamic equivalent,” translating into English the thoughts of the original text? When does a translation become a paraphrase instead? The feelings of Christians on these questions can raise the temperature of any room several degrees.

Some words that appear in the original Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek still do not make sense because our knowledge of these languages is incomplete. In other cases a scribe made an error in copying a word, and the translator today is forced to guess what he intended to write. He can check the word as it appears in Bible manuscripts translated into other languages, or he can check other manuscripts that contain the same word or phrase.

Written translations of the Bible have been made since lews living in Egypt in the third century B.C. demanded a Greek translation of the Old Testament because they could no longer understand Hebrew. One evangelical author has called this translation, the Septuagint, “by far the oldest, most important and most influential translation of the Bible in any language” (Eugene H. Glassman, The Translation Debate). This was the translation used by most of the authors of the New Testament, and possibly by our Lord himself.

In the late fourth century A.D., Latin-speaking Christians were unhappy with the poor translations then available, so jerome, the most learned Bible scholar of his day, produced the Vulgate, the Latin translation used down to the twentieth century by Roman Catholics.

The King James Version of 1611 was not the first English translation of the Bible. In fact, almost a dozen major translations had appeared in England before it was published. They include the Wycliffe Bible of about 1380, the Tyndale Bible (1526), the Coverdale Bible (1535), Cranmer’s “Great Bible,” so called because of its size (1539), the influential Geneva Bible (1560), which the Pilgrims brought to America, and the Bishops’ Bible (1568).

In the years after 1611 the negative feelings some Christians felt for the King James Version were as intense as those some people today have for the translations of the last three decades. The Pilgrims, for example, did not like the new fangled King James Version, much preferring the more traditional Geneva Bible.

Gradually, however, the King James Version supplanted all other English versions to become the “authorized” English version of the Bible.

It has never been the only translation available, however. A century and a half after the translation of King James, English had changed so much that Christians clamored for a Bible they could understand. The King James Bible we use today is not the 1611 version but was revised in 1769. One scholar comparing the two editions has compiled a list of four pages of verbal differences. In fact, the 1769 edition was the fourth such revision of the 1611 version.

Of the many translations of the Bible made in the nineteenth century, only one is widely known today. The English Revised Version produced in England in 1885 by a team of 65 Bible scholars was further revised for an American market and published in 1901 as the American Revised Version or American Standard Version.