The Grey Fox

Zoetrope Studios, United Artists Classics

It is no exaggeration to say, as some reviewers have, that The Grey Fox, could have been filmed by Ansel Adams. This movie, a product of the Canadian Film Development Corporation, is visually stunning throughout, a cinematic work of art. At the same time, intentionally or otherwise, it raises questions about the role of film in modern society.

It is 1901. Bill Miner, a crafty old robber, is released after 33 years in prison. Times have changed; stagecoaches have gone the way of the brontosaurus; horses share the streets with cars. There are things called moving pictures. The question is: how will Miner adapt to the new age?

The answer is a parable to the power of film. George Lucas, who ought to know, believes that the movies have usurped the place of the church and family. Cinema is inherently weak at exploring inner, moral struggles, and The Grey Fox is no exception. Miner makes attempts to “go straight” but finds it constricting. He watches a train robbery film spellbound, like a child viewing Star Wars. Soon thereafter, he leaves his job, buys a gun, and begins robbing trains. He has found his place in the new age. Film has been his guide. For many others, it still is, as myriads of women dressed in the slob chic of Flashdance verify.

The Grey Fox also provides a textbook example of the way crime is often dealt with in movies and on television. Behind every criminal is a “respectable” felon, in this case the old standby of a cigar-chomping capitalist, manipulating his squads of stooges. Miner is portrayed as something of a victim, as well as a Robin Hood type, excused by the populace because he only steals from the railroad. But Christians find it hard to pull for a hero who is clearly in the wrong, however historically accurate she or he might be, and however good the performance, which, in the case of Richard Farnsworth as Miner, is good indeed.

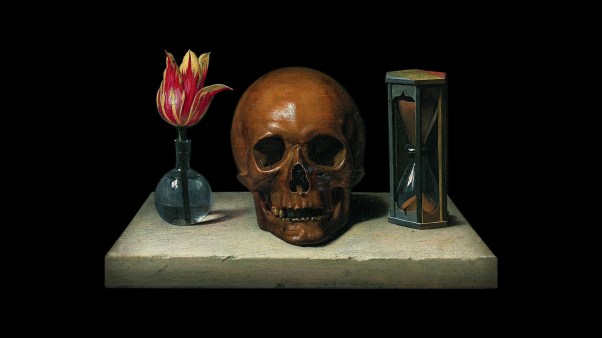

Thus, The Grey Fox, though an interesting, unconventional film, bears out a statement of Simone Weil: “Fictional good is dull and boring, but fictional evil is exhilarating and full of charm.”

Reviewed by Lloyd Billingsley, a writer living in Southern California.