Some feel the movement has peaked, while others say it is merely gaining wider acceptance.

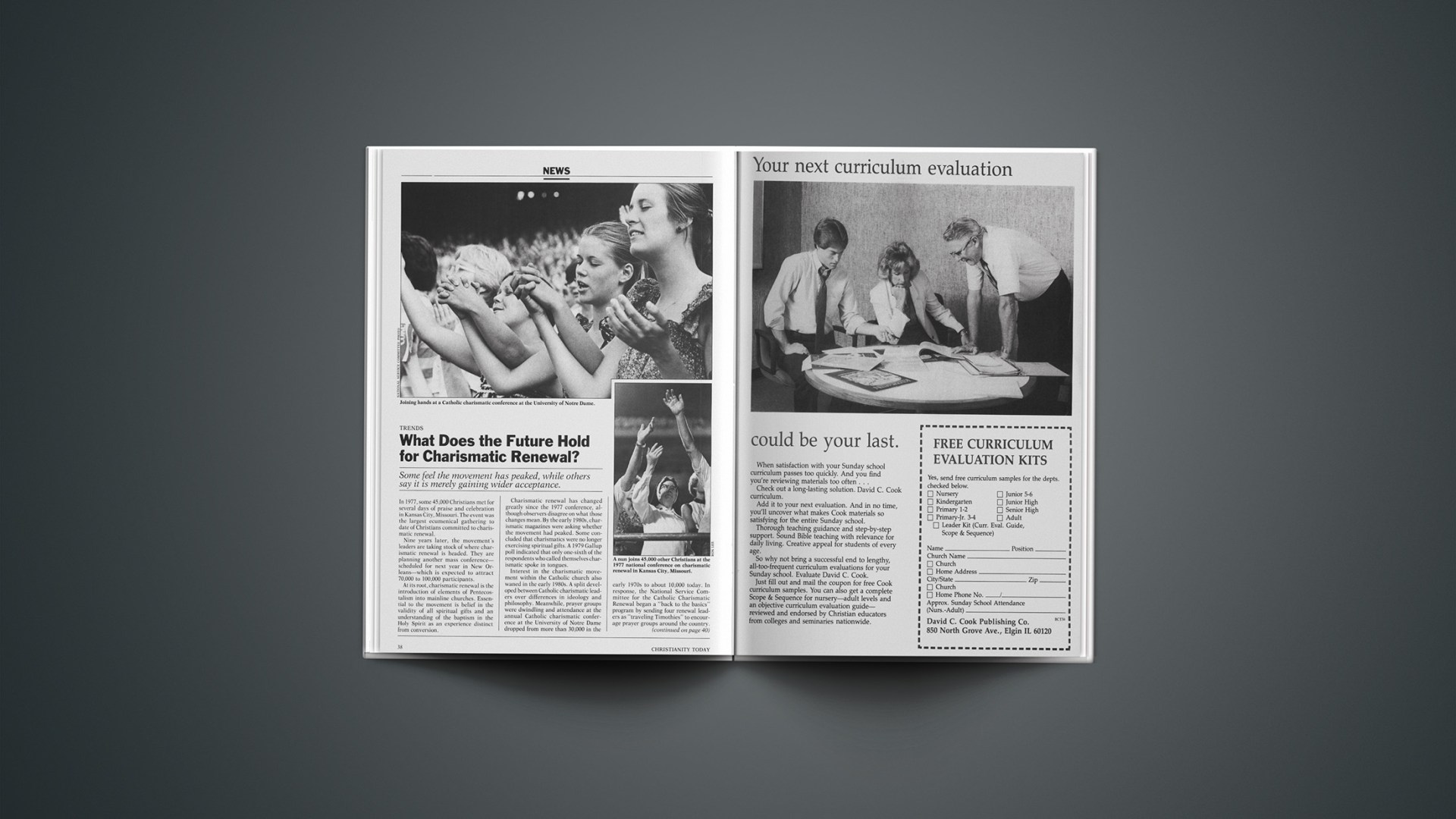

In 1977, some 45,000 Christians met for several days of praise and celebration in Kansas City, Missouri. The event was the largest ecumenical gathering to date of Christians committed to charismatic renewal.

Nine years later, the movement’s leaders are taking stock of where charismatic renewal is headed. They are planning another mass conference—scheduled for next year in New Orleans—which is expected to attract 70,000 to 100,000 participants.

At its root, charismatic renewal is the introduction of elements of Pentecostalism into mainline churches. Essential to the movement is belief in the validity of all spiritual gifts and an understanding of the baptism in the Holy Spirit as an experience distinct from conversion.

Charismatic renewal has changed greatly since the 1977 conference, although observers disagree on what those changes mean. By the early 1980s, charismatic magazines were asking whether the movement had peaked. Some concluded that charismatics were no longer exercising spiritual gifts. A 1979 Gallup poll indicated that only one-sixth of the respondents who called themselves charismatic spoke in tongues.

Interest in the charismatic movement within the Catholic church also waned in the early 1980s. A split developed between Catholic charismatic leaders over differences in ideology and philosophy. Meanwhile, prayer groups were dwindling and attendance at the annual Catholic charismatic conference at the University of Notre Dame dropped from more than 30,000 in the early 1970s to about 10,000 today. In response, the National Service Committee for the Catholic Charismatic Renewal began a “back to the basics” program by sending four renewal leaders as “traveling Timothies” to encourage prayer groups around the country.

The Third Wave

Instead of interpreting recent trends as a decline in the renewal movement, some observers say it is simply gaining wider acceptance. As an example, they point to a phenomenon known as the “Third Wave,” which blurs the distinctions between charismatic and noncharismatic Christians. (The “first wave” is the classical Pentecostal movement, and the “second wave” is charismatic renewal.)

C. Peter Wagner, professor of church growth at Fuller Theological Seminary, coined the term “Third Wave” to describe people who believe in the power and gifts of the Holy Spirit without adhering to charismatic or Pentecostal theology or worship styles. In the Third Wave, even those who speak in tongues refuse to call themselves charismatic.

“We see the Third Wave as serving church traditions that come from a Reformed theology that haven’t been involved in ministry in the supernatural,” Wagner says. “We teach how this kind of ministry can be carried out in a noncharismatic church without being divisive. And we don’t stress tongues.”

The Third Wave has its critics, including Howard Ervin, professor of Old Testament at Oral Roberts University. “It is an attempt to make [charismatic renewal] palatable to the evangelicals,” Ervin says. “There’s an attempt—unconsciously, perhaps—to play down a Pentecostal hermeneutic.”

The tendency to downplay charismatic gifts is encouraged by evangelicals who “are accepting and patronizing the charismatic renewal but not really accepting its insights,” adds retired Episcopal clergyman Dennis Bennett. “Instead, the leaders of the renewal seem to be accepting more and more the evangelical position that every Christian has the baptism in the Spirit as part of the New Birth, which is clearly unscriptural.”

Wider Acceptance

The outlook is encouraging for charismatics and Pentecostals. Fuller Seminary missiologist Donald McGavran says supernatural signs and wonders have been an effective component in world evangelization, especially in Brazil, Chile, and South Korea.

According to David Barrett, editor of World Christian Encyclopedia, Pentecostals and charismatics numbered an estimated 100 million worldwide in 1980. He says that number jumped to about 150 million by 1985.

The National Service Committee for the Catholic Charismatic Renewal says one-third of the Catholic nuns and one-fourth of the priests in South Korea are charismatic. In Singapore, Anglican bishop Moses Tay says most of his parishes and nearly all of his clergy are charismatic. And in Africa, renewal is spreading rapidly because of the large number of charismatic Anglican bishops, says British renewal leader Michael Harper. So many Anglican bishops in Africa have become part of the renewal that some Lutheran bishops are following suit, he says.

As for the United States, there are indications of a growing acceptance of some, if not all, aspects of charismatic renewal. United Methodist renewal leader Ross Whetstone conducts a healing service once a week at the denomination’s Nashville headquarters. And he says United Methodist seminaries are recruiting charismatic professors to teach evangelism.

Campus Crusade for Christ, a ministry that prohibited its staff from speaking in tongues in the mid-1960s, changed that policy in 1983. The organization returned to an earlier policy of allowing staff to pray in tongues privately, but not in public. Campus Crusade leaders are quick to note, however, that staff members are still forbidden to encourage others to pray in tongues.

The charismatic movement has found official acceptance in the Roman Catholic Church. Pope John Paul II has commended the renewal to Catholic priests. And the International Catholic Charismatic Renewal Office occupies an office at the Vatican.

Charismatic renewal is at the heart of the Catholic church, says Michael Scanlan, president of the University of Steubenville, in Steubenville, Ohio. Scanlan says supernatural healing has become more popular, and songs originating from the renewal have become a regular part of Sunday morning worship for millions of Catholics.

“Evangelical language has become accepted in the Catholic church through the charismatic renewal,” he says. “Catholics talk of having a ‘personal relationship with the Lord.’ Our students carry around Bibles all the time. On this [university] campus, altar calls are normal.”

Among major Protestant denominations, the Episcopal Church has been the most receptive to the movement. Episcopal Renewal Ministries coordinator Charles Irish says 35 of the 149 active Episcopal bishops are charismatic. He adds that 3,000 of the 13,733 Episcopal parish priests are charismatic, as are 18 percent of the laity.

Don LeMaster, pastor of the West Lauderdale Baptist Church in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, estimates that 5 percent of Southern Baptist congregations are openly charismatic. “Southern Baptists have been more cautious,” he says. “As Southern Baptists have found out that churches were charismatic, they disfellowshiped them.”

Brick Bradford, general secretary of the Presbyterian and Reformed Renewal Ministries International, estimates that 10 to 15 percent of the Presbyterian clergy are charismatic, but only a handful of their congregations are. Members of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) and the small Evangelical Presbyterian Church support the renewal more so than other Presbyterian denominations, he says.

Whetstone estimates that 1.7 million United Methodists—about 18 percent—are involved in the renewal. Clergy are holding back, he says, because “they tend to be conditioned by their seminary training. Many of them are in the closet.”

At least 10 percent of the U.S. Lutheran clergy is charismatic, says Larry Christenson, who heads the International Lutheran Renewal Center. But he says none of the U.S. Lutheran bishops has aligned with the movement.

Views From The Outside

Denominational leaders register mixed feelings about the movement. David Preus, presiding bishop of the American Lutheran Church, says as many as 10 percent of his church’s congregations have charismatic prayer groups.

“It was a source of great contention 10 to 15 years ago, but it’s become part of the landscape now,” he says. “It’s been a significant source of renewal, and we’ve recognized it as legitimate.”

However, the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod is much less open to the movement. In 1977 and 1979, the denomination forbade its pastors to teach that baptism in the Spirit is scriptural or that charismatic spiritual gifts are valid in the twentieth century. Samuel Nafzger, director of the denomination’s theological commission, says charismatic pastors have been removed from churches, and charismatic seminarians have been denied ordination.

“It’s been a problem when charismatically inclined people give the impresssion that these gifts are God’s will and that those who don’t have them are missing something that God wants them to have,” he says.

Similarly, Jimmy Draper, former president of the Southern Baptist Convention, says: “When you find evidence of the charismatic movement in Southern Baptist life, it’s been divisive.”

James Andrews, stated clerk of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), says charismatics have had little impact on his denomination. “We recognize the legitimacy of the charismatic experience, but it’s just not our style,” he says. “Presbyterians are deliberate and rational people. They like things written down in concise statements. But with the charismatic movement, you can’t write about it. You have to experience it.”

Looking Ahead

While the debate continues, charismatic leaders are planning a national conference. Called the North American General Congress on the Holy Spirit and World Evangelization, the event is scheduled for July 22 to 26, 1987, in New Orleans.

The conference is being chaired by Vinson Synan, who resigned his position as assistant to the general superintendent of the Pentecostal Holiness Church to work full-time organizing the event. Already, the event has attracted wider support among Pentecostals than did the 1977 conference, while retaining the participation of Catholics, who are expected to make up 50 percent of the conferees.

“We believe the Holy Spirit will reveal direction to us as we meet and worship and pray together,” Synan says. “After 1977, ecumenical gatherings were low on people’s lists of priorities. But now they see they need the strength of the whole movement.”

JULIA DUIN

In Search of a Charismatic Theology

Those outside the charismatic movement point to the difficulty of developing a theology for a phenomenon based largely on experience. Indeed, charismatic renewal has long been labeled as a movement in search of a theology.

But there are signs of change. Roger Stronstad, dean of education at Western Pentecostal Bible College in Abbotsford, British Columbia, recently wrote The Charismatic Theology of St. Luke.

In a foreword to the book, Clark Pinnock writes: “Watch out, you evangelicals,the young Pentecostal scholars are coming! We are going to have to take them seriously in the intellectual realm.…” Pinnock is professor of systematic theology at McMaster Divinity College in Hamilton, Ontario.

Stronstad holds that Luke’s definition of the phrase “baptized in the Spirit” pertains to an experience for the already converted. He says theologians have confused Luke’s definition with Paul’s meaning of the term, which refers to conversion or initiation.

“There is some good theological work being done on the doctoral level by Pentecostals,” Stronstad says. “Now we’re putting our stuff into print and answering our critics.”

Russell Spittler, an associate dean at Fuller Theological Seminary, says that while the charismatic movement is “theologically impoverished,” such can be expected considering how young the movement is. At the same time, he notes evangelical theology is changing.

“Twenty or thirty years ago, the dominant evangelical stance was that the gifts of the Spirit ended at the apostolic age,” Spittler says. “Many evangelicals don’t buy that any more.”

Richard Lovelace, professor of church history at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, says charismatic theology is primarily “creative groping.” But he and Spittler agree that charismatic Catholic theologians, such as Kilian McDonnell, are doing the best work in the field.

McDonnell, president of the Institute for Ecumenical and Cultural Research in Collegeville, Minnesota, says charismatic theology should include denominational traditions when possible. “It’s not a matter of violating the reality of baptism in the Spirit,” he says. “A lot of Catholics believe that what happens is an actualization of what happened in confirmation. Interpretations on how it happens may differ, but the fact is, it happens.”