Inside the world’s prisons, Christians are quietly undermining the powers of this age.

I have always had a strange, intense curiosity about what happens when human beings are pressed to their limits. As a child, I used to read with quiet horror the stories in Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. Anticommunism was a national sport in the 1950s, and preachers would regale us with tales of Christian martyrs in Russia and China and Albania. I even studied Chinese, and my brother Russian, to prepare for the day our country would surely be overrun. What would happen when my faith was tested to the extreme? Would I cling to Christ or renounce him to save my skin?

As an adult, I have devoured many written accounts of Holocaust survivors, and confess to having made it through every word of Solzhenitsyn’s three-volume The Gulag Archipelago. When I read survivors’ stories, I wonder how such a plight would affect me.

The poor and oppressed, as Jacques Ellul has said, are God’s questions to us. How will we treat them? But in a different, more troubling sense, I wonder if suffering people aren’t also our questions to God. Why does he allow such pain? North American Christians live in relative comfort, with no penalty for faith. But what meaning do the lavish promises of the gospel hold for someone condemned to a life of hunger and sickness, or oppression?

Perhaps because of these nagging questions, I went last year with an old friend, Ron Nikkel, to meet some Christians in the prisons of Chile and Peru. South American jails, I knew, would provide an extreme test of faith for anyone. Chile is often featured as one of the world’s worst human rights violators. And Peruvian jails also make news headlines; 156 prisoners died in a single riot in 1985.

What does a “church” look like among lumpen people such as these: fenced in, ill-fed, vulnerable to sexual assaults, sentenced to years of misery among murderers, thieves, rapists, and drug dealers? Can the hope of the gospel survive those conditions? I decided to see for myself.

I am sitting in the midst of a church service with a distinctly Latin and Pentecostal flavor. On the platform, a “band” consisting of 18 guitarists, one accordionist, and two men wielding handmade brass tambourines is leading a rousing rendition of a folksy song called “The Banquet of the Lord.” The congregation, 150 strong, lustily joins in. Some people raise their hands above their heads. Some seem to be competing in a highest-decibel contest. A few hug their neighbors. The meeting room is overflowing, and extra faces are peering in all the windows.

Except for a few visual reminders, I could easily forget that we are meeting in one of the largest prisons in Chile. I look around at the congregation: all men, wearing a ragtag assortment of handed-down street clothes. A shocking number of their faces are marked with scars.

After the singing, a Canadian guest, conspicuous in a white shirt and tie, comes to the platform. The prison chaplain informs the crowd that this man, Ron Nikkel, has visited prisons in over 50 countries. The organization he directs, Prison Fellowship International, brings the message of Christ to prisoners, and works with governments on improving prison conditions. A dozen inmates yell a loud “Amen!”

“I bring you greetings from your brothers and sisters in Christ in prisons around the world,” Ron begins, pausing for the translation into Spanish. He is a broad-shouldered man of moderate height, in his late thirties, with a youngish, freckled face partially covered by a beard. He speaks stiffly at first; with a soft voice he is trying to project against noise flowing in from the outside—guards blowing whistles, inmates playing basketball in the exercise yard, music blaring from the cell blocks.

“I bring you greetings especially from Pascal, who lives in Africa, in a country called Madagascar. Pascal trained as a scientist and took pride in his atheism. In 1981 he was arrested for participating in a student strike. He was thrown into a prison designed for 800 men, but now crowded with 2,500 men. They sat elbow to elbow on bare boards, most of them dressed in rags and covered with lice. You can imagine the sanitation there.” The Chilean inmates, who have been listening alertly, groan aloud with sympathy.

“Pascal had only one book available in the prison—a Bible provided by his family. He read it daily, and, despite his atheistic beliefs, he began to pray. He found that science could not help him in a prison.” (Loud laughter.) “By the end of three months, Pascal was leading a Bible study every night in that crowded room.

“Much to his surprise, Pascal was released after those three months. Someone in the government had a change in heart. But here is an amazing thing: Pascal kept going back to prison! Now he visits twice each week to preach and distribute Bibles. And when he learned that 61 inmates there had died of malnutrition, he organized church groups to bring in huge pots of vegetable soup.

“Pascal shows the difference Christ can make in a person’s life. When you walk out of prison, you’ll probably want to erase it from your mind. But Pascal couldn’t do that. He believed God wanted him to go back, to share God’s love that he had found in that stinking, crowded room.”

After the story, the Chilean prisoners break out in loud applause. Ron continues, telling story after story of people who have met Christ behind bars. Then members of the congregation stand up to speak.

One of the band members, a short, wiry man with a thick scar running across his left cheek, speaks first. “They used to think I was so dangerous that they kept me in chains. And I’ll tell you why I first started going to church—I was looking for an escape hole!”

Everyone laughs, even the guards. “But there I found true freedom in Christ, not just a way to escape.”

The service goes on, gathering emotional steam. Prisoners spontaneously kneel by the rough wooden benches to pray for their fellow inmates. The singing, animated with hand clapping and foot stomping, gets louder and more boisterous. Other prisoners abandon their basketball games and crowd around the open doorway to find out what they are missing. When the foreign visitors finally leave, amid many hugs and handshakes, all the prisoners stay. They are just getting warmed up.

I can still hear strains of the prisoners’ singing as I settle with the other visitors around a long rectangular table in the prison warden’s office. The warden has asked Ron Nikkel and his guests to meet with the prison’s psychologist, sociologist, and social workers. Clearly, we are being shown one of Chile’s showcase prisons, with modern facilities and services.

The staff professionals discuss the effect of Christian faith on the inmates. They seem to view it with a spirit of benign tolerance: Sprinkle saltpeter on the inmates’ toast to help control their sex drives, and why not add a small dose of religion to help control their tempers? The chaplain and other Prison Fellowship staff members, however, believe their work among inmates can contribute far more. Using statistics and case studies, they try to demonstrate that no rehabilitation scheme will work unless it takes into account the inmates’ spiritual needs.

The discussion ranges along such lines for 30 minutes, at which time the prison warden crosses a tolerance threshold. In every way, the warden fulfills the perfect Hollywood stereotype of a South American military officer. Only a bushy mustache breaks up the stony monotony of his sallow face. His huge barrel chest serves as a perfect display board for rows and rows of multicolored military ribbons, and his shoulder epaulet sports three stars.

When the warden speaks, everyone else falls silent. “It doesn’t matter to me which faith these prisoners take to,” he announces with finality. “But it’s clear they need to change, and they’ll never do it without some outside assistance. Religion may give them the will to change that they could never develop on their own.”

As he speaks, we can still hear the prisoners singing in the courtyard chapel. “Chaplain,” he continues, “one-third of the men in this facility attend your services. You visit several times a week, but I’m here every day. And I tell you, those men are different. They don’t just put on a performance when you come around—they are different than the other prisoners. They have a joy. They share with other prisoners. They care about more than themselves. And so I think we ought to do all we can to help this fine work.” The warden’s statement promptly ends all discussion.

As we leave the prison, the worship service is finally breaking up. The prisoners are marching around the exercise yard in twin columns, singing hymns to the beat of drums and tambourines. Two hours have passed since the service started.

The taxi to downtown Santiago takes a long, circuitous route. Pope John Paul II is coming to town tomorrow, and military roadblocks have sprung up everywhere. Wherever we go, we meet soldiers with machine guns. Ron Nikkel explains that a sweeping roundup of potential troublemakers has put new strains on overcrowded Chilean prisons.

As we ride in concentric circles around the city, Ron reflects on his day at the prison, “It never fails to get to me, no matter how many prisons I visit,” he says, “to see human beings in such miserable conditions, and yet praising God. In their faces you can see a joy and love like I’ve encountered nowhere else.

“I’ve never yet visited a country that takes pride in its prisons. They all acknowledge defeat. But then the living Christ enters a prison, as we’ve seen today, and the whole place begins to shift. God chooses the weak and foolish things of the world to confound the wise and the mighty.”

Unlike the world outside, prison offers no built-in “advantages” to becoming a Christian. It hardly helps an inmate’s social status to attend a chapel service. Yet in this one prison in Chile, one-third of all inmates had joined together in as rousing a worship service as I had ever attended. They had caught the attention of the prison authorities, even the gruff warden, who could not dispute the changes evident in his prisoners, changes his professionals had never been able to produce.

“I bring you greetings from your brothers and sisters in Christ in prisons around the world,” Ron begins again, in another Chilean prison a day later. This one, shoe-horned between buildings in urban Santiago, with an asphalt exercise yard and cell blocks stacked vertically in high-rises, conveys a far more oppressive feeling.

The prison chapel, located in a basement, is especially gloomy. To save on energy costs, prison officials have disconnected every other fluorescent lamp in the ceiling. I’m beginning to wonder if prisons are designed by architects competing to produce the world’s ugliest buildings. All walls are square, functional, and free of ornamentation. Surfaces consist of rough concrete or smooth iron bars, with no mediating textures like tile, carpet, or wallpaper. Prisons strip human inventions, just like human beings, to the barest essentials.

“I bring you greetings especially from Dr. Appienda Arthur of Ghana, in West Africa. Dr. Arthur committed no crime. He served as a member of Parliament and a close adviser to the president of Ghana until a military coup overthrew that government. Dr. Arthur landed in prison.

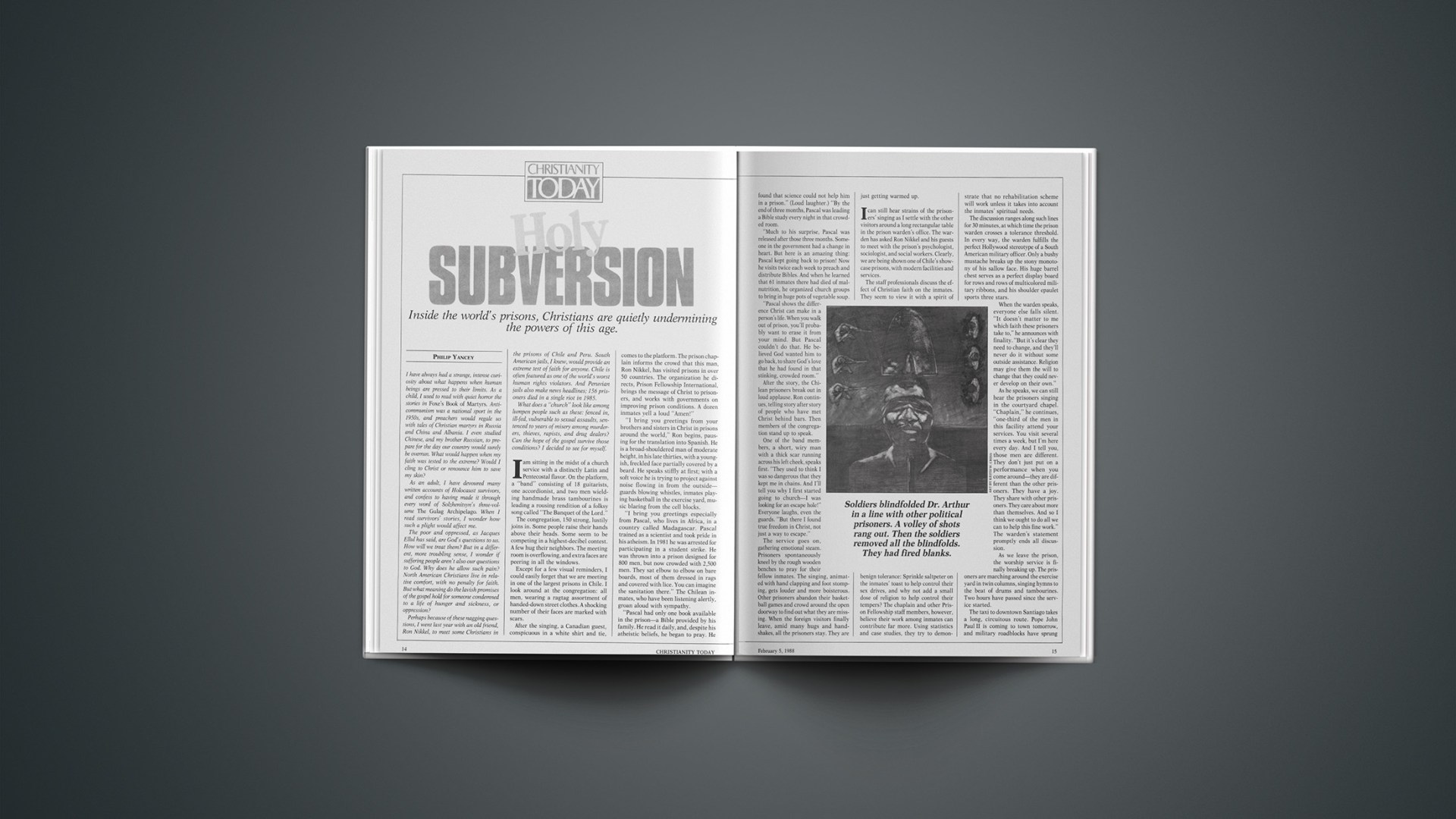

“One day soldiers marched Dr. Arthur out into a field, handed him a shovel, and ordered him to dig his own grave. When he had dug deep enough, he was blindfolded, with his arms tied behind his back. He stood in a line with other political prisoners. A volley of shots rang out. The prisoners crumpled to the ground, moaning. Dr. Arthur thought he was dead. But then the soldiers, laughing, removed all the blindfolds. They had fired blanks, playing a cruel joke on the prisoners.

“In that prison Dr. Arthur read the Bible, and also a copy of Born Again, by Chuck Colson. He was moved by the story of a man who, like him, had fallen from power and served time in jail. He knelt on the floor of the prison and promised God he would spend the rest of his life serving him. Dr. Arthur made his way to Fuller Seminary in the U.S., where he studied the Bible. He could have gotten political asylum and stayed there. Instead, he decided to return to Africa, to Ghana, the country that had almost killed him, to serve Christ.

“You can find Dr. Appienda Arthur back in prison today. But he’s there voluntarily, directing the work of Prison Fellowship in Ghana.”

By now the Chilean inmates are nodding and interjecting “Amen!” and “Hallelujah!”

In a pattern that has already become familiar, Ron tells a few more stories. He announces that one of their fellow inmates was released just yesterday on parole and is now helping with the prison workshops in Santiago. The inmates cheer. And then some of them rise in their seats to give personal testimonies.

As the chapel service continues, the military director of the prison motions for us to follow him. We get a hurried tour of the dreary facility through an endless maze of tunnels and iron gates. Two things stand out: the odor of a 40-year buildup of disinfectant, and the large framed face of General Pinochet glowering at us from many walls.

Nothing has prepared me for the director of the oldest prison in Chile. If yesterday’s director was straight out of central casting, this one must be on loan from “Saturday Night Live.” He wears a rumpled green uniform devoid of badges, ribbons and stars. He dashes around his office in a whirlwind, arranging chairs, showing off his display case collection of swords and knives, making little jokes. His eyebrows dance up and down as he talks, so that in facial expression and mannerisms, he reminds me of Pancho, sidekick of the Cisco Kid.

The director apologizes for a shortage of coffee cups. “I only have three,” he says, winking. “Drink fast, and then I’ll rinse out the cups and serve the other guests.”

As Ron Nikkel begins to explain Prison Fellowship to him, this funny man suddenly raises his hand to interrupt. “Ah, but we must have music!” he says. “Do you like disco music, my friends?” he asks. He rushes over to an oversized white plastic cassette player with the brand name Disco Robo. A Latin rhumba beat soon fills the room, and the director returns to his desk with a broad smile, motioning for Ron to continue.

It is a scene straight out of Kafka. Most human-rights organizations rank Chilean prisons near the bottom of the scale; as many as 7,000 people have died at the hands of Pinochet’s regime. Foreign news sources are reporting this week that 400 of Chile’s 700 political prisoners are on hunger strike for more humane conditions. And yet we sit in the director’s office at one of those prisons juggling coffee cups and tapping our toes to rhumba music.

The ironies carry over into the evening. We eat dinner in one of Santiago’s finest restaurants, as the guests of a wealthy man concerned about prison ministry in Chile. Around the table sit Prison Fellowship staff members, the local board, and several representatives from General Pinochet’s government. The restaurant presents a floor show based on Easter Island themes, and soon the stage is alive with beautiful women dressed in brightly colored skirts and coconut-husk tops. Shouting through translators over the din, we try to discuss prison policy.

I think of a chapter in The Oak and the Calf, in which Alexander Solzhenitsyn describes a visit to the Moscow offices of the gulag administration. He has now become famous, and there, in the plush surroundings of that office, swilling vodka with his genteel, affable hosts, Solzhenitsyn can barely recall the terrors of his life as a prisoner in the gulag. His friends still in prison seem very far away.

Ron Nikkel says very little at such social gatherings.

The next day Ron talks about his dilemmas. The Pope has arrived in Santiago and the entire country has shut down for the event. We sit in a fifth-floor hotel room beside an open window. Below us, the street is filling with thousands of people who have come for a glimpse of the Pope’s motorcade.

“Sometimes I feel like a commuter,” Ron begins, “only I commute in and out of other people’s pain. Yesterday we spent the morning inside a prison full of agony. Then we dined with the distinguished and decorated men who control those prisons. That paradox tears me apart. I return home after every trip drained and perplexed. How can we work both with the oppressors and the oppressed? That’s my real dilemma.”

From the very beginning, Prison Fellowship decided not to be an advocacy organization like Amnesty International. Advocacy groups ally themselves with a few prisoners and pressure the governments to provide better conditions.

Prison Fellowship, along with most prison ministries, uses a different approach. It focuses on volunteers—local people, families, concerned Christians—who can provide an essential human link for the prisoners. Volunteers have always visited prisoners, providing food and money and essential services. But the prison authorities usually view the volunteers as irritants: more people to search, more potential accomplices in prison breaks, more sources for drugs. People like Ron and the national directors must convince the prison authorities that volunteers can actually help their prisoners by ministering to social and spiritual needs.

The organization gets caught between the two groups. Ninety percent of its time and energy goes toward direct contact with prisoners. Yet they dare not jeopardize good relations with authorities, who could suspend their work in a minute.

Ron likes to cite Winston Churchill’s observation that a civilization can be measured by the way it treats its prisoners. Prisons are the garbage heaps of society. Just as you can learn about the lives of apartment dwellers by sifting through their garbage cans, you can sift through a nation’s prisons and learn about the larger society. More than a human experiment is under way. Prisons offer a proving ground for political and social theories as well.

Most societies do not fare well in such an analysis. Oddly, societies that promise their citizens the most tend to have the most prisoners. Consider the three nations with the highest percentage of prisoners: the Soviet Union, South Africa, and the United States. In the Soviet Union, prisons refute the deep Marxist belief about a “new socialist man” emerging. Marxism has not changed the essential nature of human beings; a tour of the gulag will confirm that. And people like Solzhenitsyn and Sakharov keep surfacing to expose the official doctrine.

In South Africa, overflowing prisons prove that a minority race can only impose doctrinaire racism on other peoples through the application of force. And in the U.S., prisons demonstrate that freedom and a land of plenty are not enough to meet human needs.

Ironically, Ron sees the utter failure of penal systems around the world as Prison Fellowship’s greatest boon. “If I were to write a book about the strategy of Prison Fellowship, I would title it Holy Subversion,” he says. “Can we subvert the world’s powers by working with their rejects, the prisoners?

“Marxists fail at their prisons, as do Muslims, Hindus, and secular humanists. Nothing works. Societies shut prisoners out of sight because they’re an embarrassment, an admission of failure. But they let prison ministries in, figuring we can’t worsen an already hopeless situation. And there, behind those bars in the least likely of all places, the church of God is taking shape.

“It’s a New Testament church in its purest form. In Chile, for example, there are 5,000 different denominations and church groups. But in Chilean prisons, the Christians are one. Prison abolishes all the normal distinctions between denomination and race and class. Around the world, everyone is equal in this fellowship united by suffering.

“I cannot give details on some of the most exciting frontiers. I can only say that in societies so closed that they apply the death penalty for a conversion to Christianity, prisons are opening doors to us. Authorities are allowing us to conduct seminars and distribute Bibles. Nothing else has worked in those prisons, so in desperation they turn to the Christians. And even in decadent Western Europe the church is showing signs of life—the church behind bars, that is.”

You do not read about such works of God in U.S. newsmagazines. They report mostly on controversies within the church: scandals among evangelicals, liberation theologies in Latin America, the ascendance of Islam in Northern Africa. But something else is taking place at the grassroots level—below the grassroots level, even, in societies’ “garbage heaps.”

In the U.S., ministry among prisoners is expanding at an unprecedented rate. In Northern Ireland, former IRA terrorists now take Communion alongside Protestants they had once sworn to kill. In Papua New Guinea, prison ministry is led by a judge who used to sentence people to the jails he now visits in the name of Christ. And Ron Nikkel can rattle off many stories of people who, like Pascal in Madagascar and Dr. Arthur in Ghana, return voluntarily to the prisons they barely survived as inmates. As Holocaust survivors bore eloquent witness to the power of evil, individuals and groups in prison are bearing witness to the transforming power of Christ.

“I bring you greetings from your brothers and sisters in Christ in prisons around the world,” Ron Nikkel says once more, to another group of prisoners. We are in Peru now, and the international travel, combined with long evening meetings with prison volunteers and embassy staff and penal authorities, has taken its toll. Ron’s face wears the fatigue of the past week.

Our meeting room adjoins a row of cells, so that in addition to the 60 prisoners in our room, a few others are diffidently watching the proceedings from their beds. Four bunks, eight beds, are crammed into rooms 8 feet deep and 16 feet wide. In prison, you learn to live with certain things: congestion, constant background noise, ever-glowing light bulbs, an utter lack of privacy. Peru’s prisons are advanced enough to have a commode in each cell—it sits in the center of the cell, visible from all sides.

Still, the rules seem looser here in Peru, as shown by the decorations covering cell walls. Hand-drawn pictures of Jesus or Sunday-school-art paintings of the Virgin vie for popularity with centerfolds from Peruvian porno magazines.

Ron tells the group about a few of the prisoners we met in Chile. He has an enormous pool of stories to draw from: spectacular tales of drug running, intrigue, violence, despair, and finally conversion. “I could bring greetings from thousands of such prisoners,” he says. “The world says they are failures and have no hope of change. But I have seen the changes.”

Today, however, Ron keeps the stories short. He feels like preaching. “Did you know that Jesus Christ was a prisoner?” he asks the scruffy-looking group. From their facial expressions, it appears that, no, they did not know that. “Well, he was. Jesus came to Earth so that God could experience all that we experience here, and that included going to prison.

“Do you know what it’s like when someone squeals on you—turns you in to the authorities?” Vigorous affirmative nods. “Jesus felt that too. One of his best friends turned him in on a trumped-up charge. Justice was no better in his day than in ours. The government broke all the rules during his trial, and sentenced him to death.

“And when he died on the cross, a prisoner died on each side of him. One prisoner taunted him: ‘If you’re really the Christ, get us out of here!’ I’ve talked to many prisoners with exactly that same attitude toward God. Some of you may be angry at God. You won’t listen to him unless he gets you out. But the prisoner on the other cross had a different spirit. He said simply, ‘Jesus, I’m guilty but you’re innocent. Please remember me.’

“And listen, only one person in the Bible receives a direct promise of heaven. It’s a thief who lived a life of crime, who did not get baptized, and who probably never went to church. He died within hours after accepting Christ. Yet that thief lives in heaven today. Jesus guaranteed it.”

Ron is warming to his audience, using hand motions, speaking with more force. The tiredness has drained away. He’s preaching like a southern black preacher now, stating a Bible story in simple terms, then embellishing it. “Sometimes, when I ask a person to go with me into a prison as a volunteer, they’ll say, ‘No, Ron, I’m scared. I don’t like hanging around thieves and murderers.’ If they really feel that way, then they had better not go to heaven, because I know of at least one thief who will be there, and a few murderers, too!”

The prisoners are eating it up. Ron runs through the Bible telling prison stories, expounding on John the Baptist’s prison-induced doubts and reading from Paul’s Prison Epistles.

After half an hour of preaching to an increasingly receptive audience, Ron turns the meeting back over to the prisoners. Many of them come to the front and tell of the difference Christ has made in their lives. Judging by the prisoners’ reactions, the biggest surprise is Juan. Leaning on the shoulder of a woman volunteer named Marie, Juan limps forward to tell his story. The other inmates know him well, for Juan has a reputation as a troublemaker. He limps because of a run-in with prison guards. He assaulted one of the guards, and other guards gave him a beating that broke his hand, bruised his face, and left him lame.

Juan speaks in a husky voice. The very act of speaking causes him great pain, and he explains why. While in solitary confinement after the beating, he somehow obtained a can of insecticide and swallowed it. Guards found him in his cell, near death. After that dark night, Marie, a volunteer, began visiting Juan with her special mission: she wanted to give him a reason to live.

Marie suddenly interrupts Juan’s story to explain that she herself is living on borrowed time—doctors have discovered an inoperable tumor in her stomach. She points to the kerchief wrapped around her head; radiation caused most of her hair to fall out.

She told Juan in the hospital room, “How dare you take your life when I would do anything to stay alive! You have no right—your life belongs to God.” And through her witness, Juan became a Christian.

As Juan and Marie finish their story, Juan asks the 60 men around him for help in the days ahead. Other inmates will surely scoff at his conversion. The group kneels together to pray for the healing of Juan’s body and the strengthening of his faith through difficult times ahead. And as they pray, a warden leads Ron and the rest of our visiting group to another circle of 60 men awaiting us in a different cell block.

Late that afternoon, as we sit in a taxi in Lima’s rush-hour traffic, Ron admits that he used to hate speaking to groups of prisoners. It seemed outrageous to use words such as hope and freedom and love when he knew he would walk out of the prison a free man, leaving them in their misery. What did he know about hope and freedom? What could he possibly offer them?

His confession intrigues me. I have known Ron for ten years, and I would never have expected from him a sermon like this morning’s. Ron always had a cynical edge to him. Like many of his generation, he bore scars of extreme fundamentalism that made him tentative, skeptical. I ask him what has changed.

“I came to this job with professional training in criminology, and of course I still try to incorporate everything I learned. But I have gradually become convinced that the lasting answer to prison problems is not rehabilitation, but transformation. Initially, I hesitated to use phrases like ‘Christ is the answer,’ but, frankly, I’ve seen that phrase proved true. I learned certain words in childhood, but the prisoners themselves finally gave meaning to those words. They proved the reality of a theology that had been little more than a mental exercise for me. They showed me faith at its most basic—the opposite of the kind of health-and-wealth theology you hear in North America. Those prisoners’ lives may never improve, yet still they learn to show love and joy.

“Jesus calls blessed those who are poor, who weep, who feel hunger, who are hated and excluded and insulted by men. That’s a perfect description of many prisoners I know. But can they really be blessed, happy? To my surprise, the answer is yes. Something about the condition of severe human need makes them receptive to the grace of God. They turn to God, and they are filled. It was no accident that John Bunyan wrote Grace Abounding unto the Chief of Sinners while he was in prison.”

The computer industry has a phrase called the “table-top test.” Engineers design wonderful new products: circuit boards, hard disks, optical scanners. But the real question is, will that new product survive actual use by consumers? Will it survive if it accidentally gets pushed off a table? For Ron, prisons have become the table-top test of the Christian faith. There, simple, tough faith is put to the test every day—by people like Juan, the Peruvian man who turned to Christ after his suicide attempt failed. The eternal truth of the gospel will be tested in his life over the next few weeks.

Some people try to prove the truth of the gospel in the halls of academia, battling over apologetics and theology. Others compare the size and force of Christianity against other great religions of the world. Ron Nikkel says he just keeps going to prisons. There he finds the final testing area for forgiveness and love and grace. There he finds whether or not Christ really is alive.

I asked Ron to think back to the worst setting he had ever seen. I had taken this assignment to see how faith survives among people who are pressed to the limits. In the dismal prisons we had visited in Chile and Peru, who could dispute the joy we had found among inmates there? But did this pattern hold true around the world? Had he ever found a place of absolute despair, with no crack of hope? What was the ultimate “table-top test” of the gospel?

Ron thought for a moment, and then he told me about a 1986 visit with Chuck Colson to a maximum-security prison in Zambia. Their “guide,” a former prisoner named Nego, had described a secret inner prison built inside to hold the very worst offenders. To Nego’s amazement, one of the guards agreed to let him show the facility to Chuck and Ron.

“We approached a steel cagelike building covered with wire mesh. Cells line the outside of the cage, surrounding a ‘courtyard’ 15 by 40 feet. Twenty-three hours of each day the prisoners are kept in cells so small that they cannot all lie down at once. For one hour they are allowed to walk around in the small courtyard. Nego had spent 12 years in those cells.

“When we approached the inner prison, we could see sets of eyes peering at us from a two-inch space under the steel gate. And when the gate swung open, it revealed squalor unlike any I have seen anywhere. There were no sanitation facilities—in fact, the prisoners were forced to defecate in their food pans. The blazing African sun had heated up the steel enclosure unbearably. I could hardly breathe in the foul, stifling atmosphere of that place. How could human beings possibly live in such a place, I wondered.

“And yet, here is what happened when Nego told them who we were. Eighty of the 120 prisoners went to the back wall and assembled in rows. At a given signal, they began singing—hymns, Christian hymns, in beautiful four-part harmony. Nego whispered to me that 35 of those men had been sentenced to death and would soon face execution.

“I was overwhelmed by the contrast between their peaceful, serene faces and the horror of their surroundings. Just behind them, in the darkness, I could make out an elaborate charcoal sketch drawn on the wall. It showed Jesus, stretched out on a cross. The prisoners must have spent hours working on it. And it struck me with great force that Christ was there with them. He was sharing their suffering, and giving them joy enough to sing in such a place.

“I was supposed to speak to them, to offer some inspiring words of faith. But I could only mumble a few words of greeting. They were the teachers, not I.”

Prisons: Bulwarks Against Spiritual Bankruptcy

Bishop Desmond Tutu has said the Western world would experience a “spiritual bankruptcy” if it were deprived of the “moral capital” of its prisoners. He should know: some of his friends, distinguished spokesmen for black South Africa, have spent much of their lives behind bars. Tutu links them to a lineage that includes John Bunyan, Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., Alexander Solzhenitsyn, and Feodor Dostoevsky.

In North America we tend to think of prisons as places of confinement for thieves, con men, robbers, rapists, and murderers. But in dark times especially, when a nation’s conscience seems to atrophy, prison can provide an unintentional sanctuary for virtue. Hitler’s concentration camps produced such moral witnesses as Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Elie Wiesel, Viktor Frankl, and Bruno Bettelheim.

Political prisoners around the world are in prison for what they think, not for what they did. And those same people use their time in prison to refine their political philosophies. Nikolai Lenin, Adolf Hitler, Fidel Castro, Che Guevara, Menahem Begin, Anwar Sadat, François Mitterand, and Helmut Schmidt credit their prison experiences with helping to form their outlooks.

Thus, one by-product of Prison Fellowship International is the remarkable opportunity to minister to the future leaders of the world. In Peru, for example, certain prisons are filled with terrorists belonging to a group called the Shining Path. Who could devise an effective way to evangelize a Maoist guerrilla group? Prison ministers have that opportunity every time they enter those Peruvian prisons.

The most spectacular result of this “by-product” ministry occurred in the Philippines in the late 1970s, when the leading opposition spokesman, Benigno Aquino, was languishing in prison. Full of anger and bitterness against the Marcos regime, he used his time to study Marxism. “The guards used to let the dogs eat half my dinner and then give me what was left,” Aquino said. “I hated everyone.” Then his mother sent him Charles Colson’s book Born Again, and he found himself strangely moved by the story. “It gave me hope,” he said. He became a Christian, and because of that hope was able to survive in prison.

Unexpectedly, Aquino gained his freedom in 1980, when then-President Marcos permitted him to travel to the U.S. for heart surgery. While there he met Colson, by coincidence, on an airplane. Colson recalls the incident: “I noticed this Oriental man staring at me, and then he grabbed my arm. ‘You’re Chuck Colson! Your book changed my life.’ I’ll never forget our conversation. Benigno told me, ‘One day I will go back to the Philippines—either to serve the government or to return to prison. Either way, we’ll start Prison Fellowship there, I promised that to the Lord when I walked out of prison.’ ”

Before leaving, Aquino studied the life of Bonhoeffer, who returned to Germany during the war in full awareness of the dangers. Aquino, of course, never made it past the airplane steps in the Philippines. But his promise has been fulfilled. Prison Fellowship is now thriving in the Philippines, and in a meeting with Colson earlier this year, Cory Aquino confirmed that Prison Fellowship would always have her official blessing.

By Philip Yancey