It has been 20 years since Charles “Tex” Watson, along with other members of the Charles Manson “family,” killed five people at a home in Bel Air, California, including coffee heiress Abigail Folger and actress Sharon Tate, who was eight months pregnant.

The following night, two more people were murdered, Leno and Rosemary LaBianca, the stepfather and mother of Suzan LaBerge, 21 years old at the time. LaBerge had spent the day water-skiing with her parents. Had she not been scheduled to work the following morning, she would have accepted their invitation to stay the night.

The day after the LaBiancas were killed, LaBerge got a call from her 15-year-old brother, who had been to the house and noticed the shades were still drawn. That evening, LaBerge, along with her boyfriend and her brother, entered the house and discovered the lifeless bodies.

While shock waves from the discoveries of “the Manson murders” crossed the world, the LaBianca family went through convulsions of its own. At first no one knew who had killed the couple or why. Thus, the police were treating as suspects Suzan and other relatives—who were themselves terrified at the prospect of being the next victims.

Suzan’s response to the deaths was profound and prolonged. “Before the murders, we used to leave our keys in the car and our doors unlocked,” she remembers. “After their deaths, whenever I came home I would look in every closet, under the bed, and in the shower before I would close and lock the front door. I worked as a waitress at night and sometimes I would drive around till the sun came up because I was scared to go home.”

LaBerge, who had been rebellious in youth, says she also struggled with guilt: “They died so suddenly. I had never said I was sorry I put them through so much.”

Within just a few weeks of the murders, LaBerge lost 25 pounds and dropped out of society. “I didn’t read the paper; I didn’t watch TV. Later I began taking drugs and I ran around with the wrong crowd. I didn’t talk to anyone about what had happened to my parents. I was so sick after the murders—paranoid, withdrawn, angry at God—I almost died.”

And had she not been able to forgive the murderers, she says, she would never have recovered. But six years ago, Laberge took the first step toward finding forgiveness when she became a Christian.

“Not even a month after I came to the Lord,” she recalls, “we had a film in church called God’s Prison Gang.” Among those featured in the film was Charles Watson, describing how he had become a Christian.

“I remember watching that movie and knowing that since Jesus had forgiven me, and he had forgiven Charles Watson, I had to forgive Charles, too,” LaBerge says. “It was a matter of obedience. And as I did so, a wee voice inside me said I would meet Charles someday.”

LaBerge immediately got involved in prison ministry, and eventually, while living in New Mexico, found herself wondering about one particular prisoner, Watson. She found out he was at the Men’s Colony in San Luis Obispo, a facility she had often driven past when she lived in that area. He had a wife and two young boys, who lived outside the prison gates.

Without telling Watson who she was, she corresponded with him for a year, and spent five months waiting to get on his visitors’ roster. Finally, her visit was arranged.

“I still didn’t know whether I would tell him who I was,” she recalls. “I just let him talk. Finally he asked, ‘Where were you at the time of my crimes?’ I said, ‘Los Angeles.’ Somehow I knew it was okay to go on. I said, ‘I want you to know that I had no intention of deceiving you by not telling you this before I came to visit.’ ”

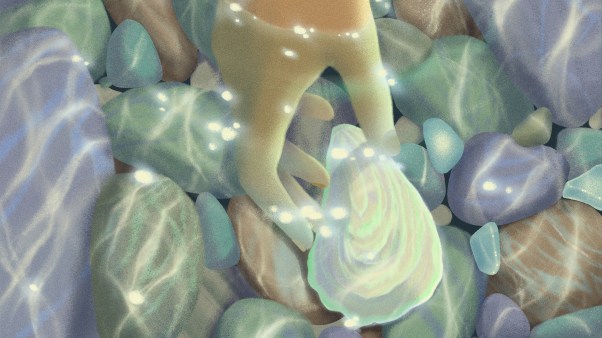

“He said, ‘Okay, what is it?’ I told him I was Rosemary LaBianca’s daughter. He thought I was kidding. It took 20 minutes of questions before he was sure I was telling the truth. I told him I forgave him. By then, we both had tears in our eyes. We held hands to pray together at the end of the visit and I thought, ‘These are no longer the hands that murdered my parents.’ ”

LaBerge remembers, “I felt so light, so free, and so unburdened. It took the boogeyman out of the murders and brought many things into perspective.”

Since that visit, LaBerge has borne a son and moved back to Southern California. She and the Watson family continue to share their lives by letter and through prison visits twice a year.

Not everything has gone right for LaBerge since her conversion. Her husband left her, and she was seven months pregnant by the time she eventually met Watson.

Of him, LaBerge says, “He did something wrong and he’s in prison for it. What he did affected many people. But when I am with him, I see only a conservative-looking gentleman with a southern accent. He’s a brother in the Lord.”

By Jessica Shaver in Long Beach, California.