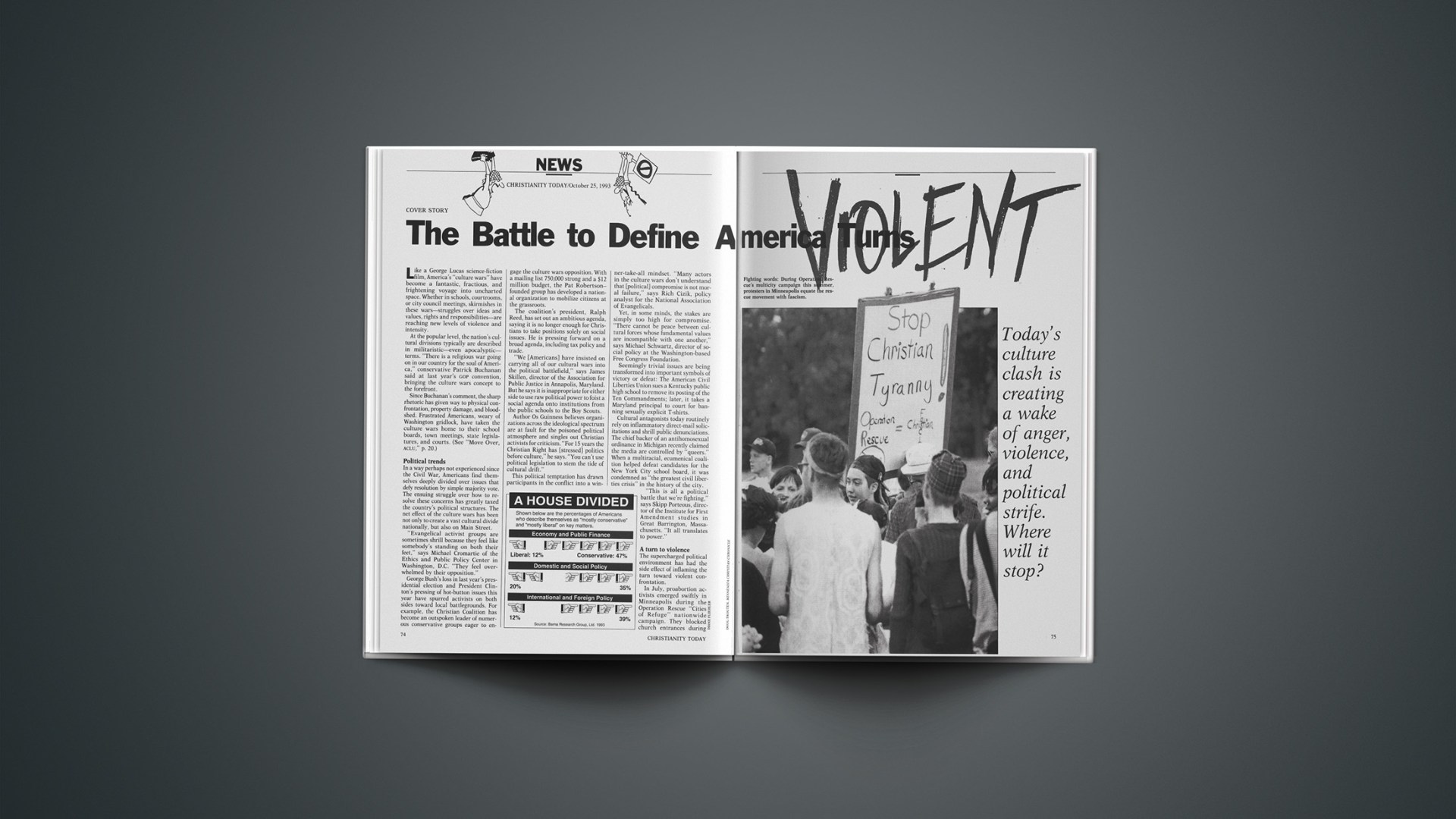

Today’s culture clash is creating a wake of anger, violence, and political strife. Where will it stop?

Like a George Lucas science-fiction film, America’s “culture wars” have become a fantastic, fractious, and frightening voyage into uncharted space. Whether in schools, courtrooms, or city council meetings, skirmishes in these wars—struggles over ideas and values, rights and responsibilities—are reaching new levels of violence and intensity.

At the popular level, the nation’s cultural divisions typically are described in militaristic—even apocalyptic—terms. “There is a religious war going on in our country for the soul of America,” conservative Patrick Buchanan said at last year’s GOP convention, bringing the culture wars concept to the forefront.

Since Buchanan’s comment, the sharp rhetoric has given way to physical confrontation, property damage, and bloodshed. Frustrated Americans, weary of Washington gridlock, have taken the culture wars home to their school boards, town meetings, state legislatures, and courts. (See “Move Over, ACLU,” p. 20.)

Political trends

In a way perhaps not experienced since the Civil War, Americans find themselves deeply divided over issues that defy resolution by simple majority vote. The ensuing struggle over how to resolve these concerns has greatly taxed the country’s political structures. The net effect of the culture wars has been not only to create a vast cultural divide nationally, but also on Main Street.

“Evangelical activist groups are sometimes shrill because they feel like somebody’s standing on both their feet,” says Michael Cromartie of the Ethics and Public Policy Center in Washington, D.C. “They feel overwhelmed by their opposition.”

George Bush’s loss in last year’s presidential election and President Clinton’s pressing of hot-button issues this year have spurred activists on both sides toward local battlegrounds. For example, the Christian Coalition has become an outspoken leader of numerous conservative groups eager to engage the culture wars opposition. With a mailing list 750,000 strong and a $12 million budget, the Pat Robertson-founded group has developed a national organization to mobilize citizens at the grassroots.

The coalition’s president, Ralph Reed, has set out an ambitious agenda, saying it is no longer enough for Christians to take positions solely on social issues. He is pressing forward on a broad agenda, including tax policy and trade.

“We [Americans] have insisted on carrying all of our cultural wars into the political battlefield,” says James Skillen, director of the Association for Public Justice in Annapolis, Maryland. But he says it is inappropriate for either side to use raw political power to foist a social agenda onto institutions from the public schools to the Boy Scouts.

Author Os Guinness believes organizations across the ideological spectrum are at fault for the poisoned political atmosphere and singles out Christian activists for criticism. “For 15 years the Christian Right has [stressed] politics before culture,” he says. “You can’t use political legislation to stem the tide of cultural drift.”

This political temptation has drawn participants in the conflict into a winner-take-all mindset. “Many actors in the culture wars don’t understand that [political] compromise is not moral failure,” says Rich Cizik, policy analyst for the National Association of Evangelicals.

Yet, in some minds, the stakes are simply too high for compromise. “There cannot be peace between cultural forces whose fundamental values are incompatible with one another,” says Michael Schwartz, director of social policy at the Washington-based Free Congress Foundation.

Seemingly trivial issues are being transformed into important symbols of victory or defeat: The American Civil Liberties Union sues a Kentucky public high school to remove its posting of the Ten Commandments; later, it takes a Maryland principal to court for banning sexually explicit T-shirts.

Cultural antagonists today routinely rely on inflammatory direct-mail solicitations and shrill public denunciations. The chief backer of an antihomosexual ordinance in Michigan recently claimed the media are controlled by “queers.” When a multiracial, ecumenical coalition helped defeat candidates for the New York City school board, it was condemned as “the greatest civil liberties crisis” in the history of the city.

“This is all a political battle that we’re fighting,” says Skipp Porteous, director of the Institute for First Amendment studies in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. “It all translates to power.”

A turn to violence

The supercharged political environment has had the side effect of inflaming the turn toward violent confrontation.

In July, proabortion activists emerged swiftly in Minneapolis during the Operation Rescue “Cities of Refuge” nationwide campaign. They blocked church entrances during Sunday services, staged a “queer kissin,” and vandalized vehicles. Several activists were arrested.

One group’s literature called for “mass militant action” against prolife organizations. And in an unprecedented move, local authorities have charged prolife and prochoice activists with “stalking” each other.

Earlier this year, two abortionists were shot, one fatally, outside Kansas and Florida clinics picketed by prolife forces. A Roman Catholic priest defended one shooting on a talk show. A Pensacola, Florida, pastor has formed a group called Defensive Action, which publishes position papers justifying the killing of abortionists.

The National Gay and Lesbian Task Force has reported that incidents of antihomosexual assaults totaled 817 in 1992, up from 775 in 1991. William A. Percy, author of Outing: Shattering the Conspiracy of Silence, has offered a bounty of $10,000 to “anyone who first succeeds in outing” an American cardinal, a Supreme Court justice, or a four-star U.S. military officer.

On September 19 in another violent incident, an angry crowd of 100 people vandalized the Hamilton Square Baptist Church in San Francisco and harassed worshipers during the evening service at which Lou Sheldon, a vocal critic of the homosexual political movement, spoke to church members.

“Culture wars always precede shooting wars,” warns Culture Wars author James Davison Hunter, whose forthcoming book, Before the Shooting Begins, examines the threat of the cultural conflict to democratic government.

For at least a generation, cultural forces—involving education, the media, denominations, and the law—have been realigning into opposing camps—progressive and orthodox—that cut across traditional boundaries.

Guinness, author of The American Hour, believes a “national schism” has been fueled by a “crisis of cultural authority in which the beliefs, ideals, and values that once defined America have lost their compelling and restraining power.”

One striking aspect of this conflict is that alliances have formed among religious and social groups historically at odds. The orthodox—mobilized by religious conservatives—are drawn mostly from among the Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish faiths.

The progressives, by contrast, are led mainly by “cultural elites” in education, law, and the media, whose religious commitment is usually liberal, minimal, or nonexistent.

The realignment has generated strange bedfellows. Catholic William Bennett, a scholar in cultural studies at the Heritage Foundation, has been praised by evangelical leaders James Dobson of Focus on the Family and Jerry Falwell of Liberty University.

In Philadelphia, African-American churches recently joined with a white evangelical church, the Catholic archdiocese, and a Muslim cleric to defeat an ordinance calling for legal recognition of homosexual couples living together. The church leaders prevailed despite harassing phone calls and death threats.

Since 1990, the left-leaning American Jewish Congress has worked with the ACLU in lawsuits to compel the Boy Scouts to amend its rules so that atheists, homosexuals, and women could join. At the same time, conservative Jews such as newspaper columnist Don Feder, film critic Michael Medved, and radio commentator Dennis Prager have allied themselves with conservative Christian groups.

“I regard the demise of Christianity in America [as a] nightmare—and I say that as a believing, religious Jew,” Prager told CHRISTIANITY TODAY. “The battle is no longer Jew versus Christian, but Jew and Christian versus secular nihilism.”

How did we get here?

From the colonial era until about the 1920s, American society was predominantly Protestant in its religious and ethical beliefs. Immigration and other factors helped shift the culture toward a blend of Jewish, Protestant, and Roman Catholic traditions that lasted through the 1950s. When disputes arose over standards of morality, they were settled in the context of a society generally committed to common core values.

During the 1960s, that consensus rapidly began to unravel. Cultural historians such as Guinness, Mark Noll at Wheaton College in Illinois, A. James Reichley at the Brookings Institution, and George Marsden at the University of Notre Dame, typically point to the 1960s as the principal breach.

Where battles are fought

Between the hard edges of the progressive and orthodox positions reside the beliefs and attitudes of most Americans—a squishy middle ground where interests are divided.

This is perhaps best illustrated by the abortion debate. Though abortion has been seized upon by those on both sides of the cultural chasm, a slim majority of Americans (51 percent) think it ought to remain legal, but only under certain circumstances.

Because public schools are the country’s most important corporate means of transmitting American values, the schools have become a perennial battleground in the culture wars. Skillen says, “There are things over which we differ culturally that can’t be resolved in a state-monopolized school system.”

In 1984, Congress passed the Equal Access Act, which guarantees student religious clubs the same right to meet as other school clubs. Despite this, last month’s student-led “See You at the Pole” prayer effort sparked 250 disputes in 22 states. Meanwhile, the Renton School District in Washington State has stonewalled students who want to start a Bible study, and the case is pending in federal appeals court.

Critics say that such lawsuits, propelled by progressives, divert attention from the social decay hollowing out the nation’s school systems. William Kilpatrick’s Why Johnny Can’t Tell Right From Wrong notes that every month there are about 525,000 assaults, shake-downs, and robberies in the nation’s public schools. Roughly 135,000 students carry guns to school every day, and one-fifth go armed with a weapon.

Intellectual infantry

Equally visible and important are the debates emerging in colleges and universities, the intellectual infantry in the culture wars.

At the administrative and professorial levels, academia is dominated by progressives—most of them indifferent or hostile to religious belief, argues Marsden, author of the forthcoming The Soul of the American University.

“Protestantism was pivotal in the founding of most American colleges,” Marsden says. “But it’s almost taken for granted that higher education shouldn’t have anything to do with religious concerns.” Case in point: Ivy League universities last year pressured a Christian preparatory school to abandon its commitment to accept only professing Christians on its faculty.

“There is no soul to the American university,” he says. In its place exists an amalgam of special-interest groups. This is most visible in the rapid growth of “multiculturalism” in university curricula, in which European-based traditions are replaced by an eclectic blend of non-Western alternatives. Marsden says, “It is an odd sort of multiculturalism that does not recognize that in almost all cultures in history, religion has been a major factor.”

Shrinking religion’s role

In the early 1800s, Alexis de Tocqueville noted that “Americans have the strange custom of seeking to settle any political or social problem by a lawsuit.” The Clinton administration, which will name more than 12 percent of the federal judiciary, is not likely to reverse the American tendency to rely on litigation to bring about social change.

Senate Democrats, by delaying hearings on nearly half of President Bush’s 1992 judicial nominees, guaranteed at least 102 vacancies when Clinton took office—more than three times the number awaiting Ronald Reagan in 1981.

On nearly every hot-potato issue in the culture wars, from affirmative action to homosexuality, the conservative currents in the federal judiciary could easily be reversed by Clinton nominees.

Meanwhile, an increasing number of contests will be waged over the limits of religious liberty, says Steve McFarland, director of law and religion at the Christian Legal Society in Washington. He asks, “How small a box is the government going to be allowed to put religion in?”

Currently, religious groups are exempt from federal laws that ban discrimination in employment and housing on the basis of religion, sex, or race. However, a bill is pending in Congress that would add sexual preference to the federal list. If approved, McFarland says, it would embolden states and localities to challenge the hiring policies of churches and religious groups.

“You’re really going to see the trend toward the shrinking and elimination of exemptions for religious groups,” McFarland says. “I don’t want to see the church get mad, but get educated about our constitutional rights.”

Another judicial jab at religious freedom is over community zoning laws, in which courts have become more willing to accept zoning restrictions on growing churches. The change has occurred largely as a result of the Supreme Court’s 1990 ruling that gutted its “compelling interest” test for burdening religious expression.

Recent state court rulings reflect a deeper cultural shift in attitudes about the nature and function of churches and synagogues, says Angela Carmella, an expert in religious property use at Seton Hall University, South Orange, New Jersey. Many courts have adopted “an equality rationale,” treating religious groups no differently from their secular counterparts, regardless of how court rulings might trample a church’s right to free exercise of religion.

A way through

With ultimate values at the root of the cultural conflict, is there a way through the culture wars in America—short of a Yugoslavian-style breakup?

Cromartie, Guinness, Hunter, and others represent the view of many culture watchers in emphasizing a twopronged strategy for evangelicals.

First is the issue of discipleship: Christians simply must be more effective at penetrating the culture where they live and work, as students, educators, lawyers, artists, by shaping attitudes, assumptions, and values.

“We need to spend less time writing hate-mongering appeal letters that stigmatize the ‘demonic forces’ of the Left,” says McFarland, “and spend more time as salt-and-light candidates on school boards and public libraries.”

However, the other part of the equation is more complex: It involves a rethinking of—indeed a reformation in—the way Christians approach public life and public policy.

Such a reforging of the public philosophy would include an emphasis on persuasion, a reluctance to use power politics to impose cultural agendas, and a renewed respect for deep differences over faith and morality.

Observers on both sides of the culture divide say the principles behind the First Amendment point the way.

There seems to be much agreement that the amendment was intended to allow diverse religious faiths to flourish privately, but to encourage all to help sustain the public order—even in a thoroughly pluralistic society.

“The principle of the First Amendment … is one of the most valid ways to bring an end to the culture wars,” Porteous says. “We shouldn’t have this divisiveness.”

Guinness says it is crucial that progressives recognize the historic and vital role that religious beliefs have played in sustaining American democracy. Also, he challenges religious conservatives to defend the legitimate rights of society’s most unpopular minorities.

“We’re facing a Lincolnesque moment,” Guinness says. “The need is to have leadership that articulates a vision for America that is for people of all faiths—and of none.”

The reference to Abraham Lincoln seems especially apt. Though unable to avoid a civil war, Lincoln relentlessly summoned the nation to return to its “first principles,” including the fundamental belief in the God-given freedom and dignity of every person. And Lincoln realized that transcendent truths required more than simple legislation in binding a fractured nation: “Whoever molds public sentiment goes deeper than he who enacts statutes, or pronounces judicial decisions.”

By Joe Loconte in Washington, D.C.