How the Reformed tradition revolutionizes our approach to the spiritual life.

Spirituality is a buzz word these days. But sometimes the impression is left that Catholicism, with its long tradition of spiritual formation, is the only game in town. A well-known series of the “classics” of Western spirituality, notes Presbyterian pastor and scholar Hughes Oliphant Old, omits many of Protestantism’s most important figures. Some might conclude that there is no such thing as a Protestant spirituality.

As Old demonstrates, nothing could be further from the truth. Here he assesses the rich insights the Reformed tradition brings to piety and prayer. This is the first in an occasional series on how varied traditions can enrich our understanding of God and the spiritual life.

The Protestant Reformation was a reform of spirituality as much as it was a reform of theology.

For millions of Christians at the end of the Middle Ages, the old spirituality had broken down. Spirituality had been cloistered behind monastery walls for centuries. To be serious about living the Christian life had meant leaving the world and joining a religious community. At the heart of it all was a celibate, ascetic, and penitential devotion.

With the Reformation, the focus of the Christian life changed. Rather than separating from society, Christians began to conceive of devotion as living everyday life according to God’s will (Rom. 12:1–2). Spirituality became a matter of living the Christian life with family, out in the fields, in the workshop, in the kitchen, or at one’s trade.

Those in the tradition of Ulrich Zwingli, John Calvin, John Knox, and the English Puritans therefore came to speak of the doctrine of the Christian life when discussing what Roman Catholics call “spiritual theology.” Traditionally they have preferred the word piety over spirituality. In broadest strokes, a Reformed spirituality must be defined in terms of the Christian life in this world. What are some of its distinctives?

FED BY THE WORD

Reformed spirituality is first a spirituality of the Word. While it received renewed emphasis in the Reformation, a spirituality of the Word is nothing new to Christianity. Already in the Gospel of John we find it, especially in its opening verses (John 1:1–18), but also sprinkled throughout the text. Jesus is presented as the Word, the revelation of the Wisdom of God. The Christian life is a matter of hearing this Word and receiving it by faith. In this John was heir to the wisdom theology found primarily in Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, the Song of Solomon, and many of the Psalms. Israel’s wisdom writers developed a piety centered in the Bible. It was a piety of those charged with caring for the Sacred Book and teaching its precepts, a scholar’s piety that emphasized studying the Bible, copying its manuscripts, preserving the history of its interpretation, and preparing and preaching sermons. The foundation of its educational system was the memorization of Scripture.

The rabbis of Jesus’ day kept alive this bookish kind of piety, as did the earliest Christian church. Luke undoubtedly had this in mind when he told us that the apostles devoted themselves to prayer and to the ministry of the Word (Acts 6:4). The study of the Word of God stood at the center of the apostolic ministry. From the beginning, Christianity was a religion of the Book, and its piety was a piety of the Book.

At the time of the Reformation, this spirituality of the Word gave a prominent place to both the public preaching of the Word and the personal study and meditation on the Word. Early in the Reformation, preachers such as Martin Bucer, Zwingli, Calvin, and Knox set aside the lectionary and began to preach through books of the Bible. This was called preaching the lectio continua. It was a systematic approach to the interpretation of Scripture in worship. It aimed to explain the text of Scripture as the authoritative Word of God rather than give the preacher’s view on a variety of religious subjects. And every serious Christian was expected to study the Scriptures systematically at home.

NOURISHED BY THE PSALTER

Reformed spirituality is also a spirituality of the Psalter. It has been nourished by praying the Psalms—singing and meditating on them, both at church and at daily family prayers.

Why sing the Psalms? They are the fundamental prayers of the church. Jesus constantly prayed the Psalms, as every good Jew in his day did. The church continued the practice in ancient times, rejoicing in the way the Psalms had been fulfilled in Christ. The earliest Christians understood the Psalms as the prayers of the Holy Spirit and therefore were honored as a primary component of the prayer of the church (Acts 4:23–31).

Calvin had a profound sense of the Psalms as prayer. In the preface of the Genevan Psalter of 1542 he wrote that the Psalms are valuable for prayer because they are the prayers of the Spirit; they thereby teach us to pray as we ought, even when we are not sure how (Rom. 8:26). Isaac Watts, the English Congregationalist, wrote many hymns based on the Psalms that are still popular today. Charles Wesley produced a particularly fine collection of metrical psalms. And Christian hymn writers today produce very singable psalm versions.

It is my firm conviction that nothing would help us recover the life of prayer more than rediscovering the Psalms. Protestant spirituality is a singing spirituality. For Reformed Protestantism, a good part of that singing is going to be Psalm singing.

RECOVERING THE LORD’S DAY

The spirituality of the Lord’s Day forms another cardinal feature of Reformed piety. While the beauty of the Christian understanding of the Lord’s Day has often been obscured by Sabbatarian legalism, there is something profound about the early Christian sign of the eighth day, the first day of the New Creation (John 20:1, 26). It was Jesus himself who interpreted the old Sabbath and established the Lord’s Day by meeting with his disciples for worship on the first day of the week (John 20:19, 26).

A few years ago I discovered A Treatise Concerning the Sanctification of the Lord’s Day, a work of early eighteenth-century Scottish minister John Willison. His writing showed me the spiritual vitality of the observance of the Lord’s Day as our spiritual ancestors understood it. Part of their secret was focusing on what they were to do on the Lord’s Day rather than what they were not to do. They saw it as a day devoted to prayer and meditation on God’s Word, a day for public and private prayer.

More recently some Christians have argued that we should replace this emphasis on the Lord’s Day with a spirituality of the liturgical calendar. But the observance of Lent and Advent is antithetical to a Reformed piety. It puts the emphasis on seasons of fasting rather than the weekly observance of the resurrection of Christ. Lent and Advent become the “religious” seasons of the year while the observance of the 50 days of Easter and the 12 days of Christmas become anticlimactic. A true Reformed piety could never drape any Lord’s Day with penitential purple! To the contrary, it sees the service of the Lord’s Day as a foretaste of the worship of heaven (Rev. 1:10). That our worship occurs on the first day of the week, the day of resurrection, gives it a joyful, festive mood.

This was not just understood in narrow spiritual terms, either. The Reformed manuals of devotion always include a humanitarian dimension in the Lord’s Day observance. They speak of how Jesus made a point of healing on the Sabbath, how it was a day of releasing people from burdens (Luke 13:16). It was a day for relieving the poor.

THE SACRED MEAL

A Reformed spirituality finds in the celebration of the Lord’s Supper a sign and seal of the covenant of grace. Participation in the sacred meal seals the covenantal union between us and our God. Not only does the sacrament bring us into communion with God, it brings us into the Christian community. Communion may only be celebrated a few times a year in most Reformed churches, but when celebrated it is traditionally given a great amount of time.

Preparatory services before Communion have played an important role in Reformed sacramental piety. Churches in seventeenth-and eighteenth-century Scotland customarily held a week of services before the observance of the sacrament and followed it with several thanksgiving services. These Communion seasons were the mountaintop experiences of the Christian life. As we discover from the Communion meditations of Matthew Henry (1662–1712), minister of the Presbyterian Church in Chester, England, preparation for the Lord’s Supper was a time for the most serious devotional meditation.

Christians in those days also approached Communion as the wedding feast of the Lamb. God’s redemptive love formed a recurring theme, and the Communion sermon would often take a text from the Song of Solomon. In New

Jersey in the late 1730s we find Jacobus Theodoras Freylinghuysen and Gilbert Tennent preaching the same kind of sacramental piety as they led the Great Awakening. They invited their congregations to the Lord’s Table to experience the consummate love of Christ and to pledge their love to him in return.

SACRALIZING THE ORDINARY

Stewardship is yet another major theme of a Reformed spirituality. Reacting against the asceticism of the Middle Ages, the Reformers took the parables of Jesus concerning the good stewards and their talents as the basis for a new Christian understanding of the use of wealth (Luke 12:42–48 and Matt. 25:14–30). In the centuries that followed, Christian merchants, artisans, housewives, farmers, and bankers began to discover positive spiritual value in their work. They found in their industry, labor, and professions a true vocation. Family life, the raising of children, the support of the elderly, and the care of a home were more and more regarded as sacred trusts.

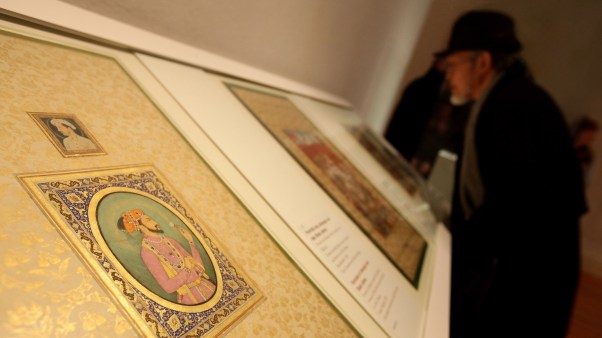

This new approach to life was beautifully expressed by the seventeenth-century Dutch painters. Vermeer, de Hooch, Hobbema, and Rembrandt showed the sacredness of everyday life as they painted the kitchens, courtyards, and country lanes in which the Dutch lived out their Christian lives.

The Puritans in both England and America gave family life a new dignity by making daily family prayer a primary spiritual discipline. Every Christian home is a little church, Puritan Richard Baxter said. In such classics as Baxter’s Christian Directory, we find a great deal on the subject of Reformed spirituality and how it functioned in the life of the family.

Part of the Re-formed understanding of stewardship is what some have called the Protestant work ethic. As maligned as it was in the 1960s, it was an essential part of the spirituality that has repeatedly delivered Protestants from poverty. Now that the sixties are long past, it is time to take another look at how a Reformed spirituality contributed to the rise of capitalism. It may well be a more positive contribution than the Marxists wanted us to believe.

THE MYSTERY OF PROVIDENCE

Finally, we consider the place of meditation on the mystery of divine providence. English Puritan John Flavel wrote the classic on this subject. He tells how the Christian, confident that God’s providence embraces all the events of our lives, gains understanding by thinking about how God is speaking to us, warning us, encouraging us, leading us through life, guiding us in his service, and finally bringing us to himself. The thoughtful Christian thinks over what Providence has brought about, he said, and, listening carefully to the Word of God, tries to discern God’s leading.

Most Christians are aware that Calvin’s theology gave great attention to the doctrines of providence and election, but many do not realize how much he absorbed these themes from the Scriptures themselves. The lives of Abraham, Joseph, and David, Calvin said, give us constant examples of how God shapes our lives. Abraham was called to a land that is described simply as a land that God would show him (Gen. 12:1). Joseph was sold as a slave into Egypt, and yet the Bible is clear that God had led him through those difficult days so that he might be a blessing to both the Egyptians and his own family (Gen. 45:7). David was anointed by Samuel to be king over Israel while he was still a boy. God alone could have ordered his life so that eventually he would ascend the throne and fulfill God’s purpose for his life (Ps. 138:8). The life of Christ, even with his passion and resurrection, was part of God’s plan for our salvation (Acts 2:23–24). The apostles saw even their own ministry as the unfolding of God’s plan (1 Pet. 2:4–10).

English Baptist Charles Haddon Spurgeon preached one of his greatest sermons on the spiritual application of the doctrine of providence. His sermon on Queen Esther shows that each of us has a divinely appointed destiny, a purpose in life. The devout life is one dedicated to fulfilling that purpose.

That fulfillment, the Reformers stressed, will find fullest expression not on the mountaintops of the spiritual elite, but in the daily lives of every believer.

Paul Brand is a world-renowned hand surgeon and leprosy specialist. Now in semiretirement, he serves as clinical professor emeritus, Department of Orthopedics, at the University of Washington and consults for the World Health Organization. His years of pioneering work among leprosy patients earned him many awards and honors.