Click here for the beginning page of this article.

This missionary mindset is quite distinct from evangelistic enthusiasm. Evangelism can be (and usually is) carried on within the constraints of a culture. For example, Jesus can be preached as satisfying modern desires for self-fulfillment. The missionary, however, sees the gospel as an invasive force, challenging culture, compelling a higher allegiance.

Since the time of Constantine, few Western Christians (including Western missionaries) have been able to look at their own societies that way. Christianity was identified with European culture (“Christian civilization”), which by definition could not be converted, since it already had been. More recently, modern Western culture offered truths to which Christianity was expected to conform. Christianity had to be converted, demythologized, or otherwise transformed to meet the requirements of Western culture.

Newbigin’s years in India developed habits of mind that he used to rethink all that. In India he had engaged a powerful, religious world-view, as intellectually sophisticated as anything in Europe. Preaching in Tamil (a difficult language that few outsiders master), he had to think through the Christian doctrines in a language formed by Hindu thought, to people accustomed to a Hindu way of thinking. He learned to read a culture with a view to its transformation in Christ.

Naming GodAs a young missionary, Newbigin regularly visited a Hindu monastery, its great hall “lined with pictures of the great religious figures of history, among them Jesus. Each year, on Christmas Day, worship was offered before the picture of Jesus. It was obvious to me as an English Christian,” says Newbigin, “that this was an example of syncretism. Jesus had simply been co-opted into the Hindu world-view; that view was in no way challenged. It was only slowly that I began to see that my own Christianity had this syncretistic character, that I too had to some degree co-opted Jesus into the world-view of my culture.” He saw this particularly when he studied the gospel accounts of evil spirits and realized that simple villagers understood them more readily than he.

The Hindu monastery belonged to the Ramakrishna Mission. In it Newbigin joined a weekly study group that read alternatively (in Sanskrit and Greek) from the Svetasvara Upanishad and John’s gospel. One member was a scholar in the vishishtadvaita philosophy, a theistic form of Hinduism with a very strong doctrine of sin and grace, memorialized by Rudolph Otto in India’s Religion of Grace and Christianity. Newbigin “set himself to school” to learn this philosophy.

“There came a moment in my meetings with this scholar when he put to me the question, ‘What do you mean by salvation?’ [In answering] I emphasized sin and forgiveness in the work of Christ. When I finished, my teacher said, ‘That’s very interesting, because what you have said, apart from the name of Jesus, is exactly what I would have said.’

“So I said, ‘In that case, tell me, what is the basis of your assurance that God does forgive your sins?’

“And without a moment’s hesitation, he said, ‘If he wouldn’t, I would go to a god who would.’

“I suddenly saw that … someone could use all the language of evangelical Christianity, and yet the center was fundamentally the self, my need of salvation. And God is auxiliary to that.

“Whereas for a Christian brought up on the Bible, the figure of God, Yahweh, this formidable, inescapable, masterly figure is so deeply engraved in our minds, that a Christian could never have said that. But it came straight off his lips, without a moment’s hesitation . …

“I also saw that quite a lot of evangelical Christianity can easily slip, can become centered in me and my need of salvation, and not … in the glory of God.

“From that time on, in preaching in India, I never started by talking about sin and salvation, I talked about God and what he has done . …

“I remember once spending a whole day with a man from a very, very primitive hill tribe, which has never been touched by what we would call Hinduism, or by Christianity. He was a cave dweller. I spent the whole day with him, following him through the jungle as he used his bow and arrow to shoot little rabbits and little animals. … I had a long talk with him, and one of the questions I put to him was, ‘Who do you think made us?’ Immediately he said Kadavul, which is one of the words for God, but it is a very basic word that is a combination of the verbal root kada, which means to go beyond, to transcend, and ul, which is the word for meaning or for being. … So Kadavul is ‘The Transcendent Being.’ It’s a wonderful word for God.

“When I preach in a village where Christianity is not known, and where the name of Jesus is not known … I have to begin by using the word Kadavul. But of course when I use the word Kadavul they’re thinking of Vishnu or Shiva or some other Hindu God. I know that, but I can’t help it. It’s only when I begin to tell the stories of what God has done that they begin to say, ‘Kadavul is not what we had thought.’ “

In a sense, these Indian experiences form the basis of Newbigin’s approach to the modern West. “Truth,” Newbigin says, “is not abstract ideas or mystical experiences, but a story of what God has done.” This is no less true in the West, where ordinary people have lost hold of the gospel story that fills God with a Christian meaning. A bold proclamation of the Bible story, especially of the historical life, death, and resurrection of Jesus, make up the central authority for Christian preaching, East or West. For Newbigin, all other apologetics take a subsidiary role. “If someone says, ‘Newbigin says it’s all a matter of faith, that means Newbigin is ultimately a relativist,’ my answer is, there is no stronger way of affirming a statement than to say I will gladly die for it.”

Wanted: Believing congregationsThat last statement catches the tip of something important. Newbigin’s writings give more than missionary thinking. He communicates blue fire. His words make a credo, a marching song. It is a spirit almost lost among modern Christians, who are (as Newbigin notes) so pleased that the church is now multicultural but so embarrassed by the method by which it came to be so.

Unlike many Christian leaders, Newbigin was never for any great length of time an academic, a church bureaucrat, or (never at all) a media savant. He has, however, done a great deal of street preaching before skeptical crowds. As a bishop in India, he set his priority on congregational ministry, traveling out to remote, illiterate villages, spending the night in local homes, conducting services in the open air. He could get on the next plane for Geneva to parley with great theologians. (Beginning in 1952, for example, he chaired the “Committee of Twenty Five,” an assemblage of feisty theologians, including Karl Barth, Emil Brunner, and Reinhold Niebuhr, leading them in drafting a statement on Christian hope.) Yet he came back to engage insistently the life of the church at a congregational level, just as he would do decades later at Winson Green after his retirement.

Newbigin would not subscribe to the most conservative of evangelical definitions of scriptural authority, but he is a biblical Christian from head to toe. As a searching, agnostic university student, Newbigin asked a friend how he would begin if he wanted to become a Christian. “Buy an alarm clock,” was the answer.

“I didn’t know whether there was a god or not, but I began taking just half an hour before breakfast to read the Bible and to pray.” He has been doing so ever since. “I do most deeply believe (and I have tried to act on that belief in many different situations) that when we are looking for guidance and renewal, fundamentally we have to go to the Scriptures” (Word in Season).

His conversion came later that year, when he helped run a holiday camp for unemployed miners in South Wales. The camp, resolutely secular, seemed to have little to offer such destitute men. One night they got roaring drunk and fought each other. Young and idealistic, Newbigin was shattered. That night in his tent he had a vision of a cross, “spanning the space between heaven and earth.” It seemed to promise hope from God, reaching into the most dire circumstances. “I was sure that night, in a way I never had been before, that this was the clue that I must follow if I were to make any kind of sense of the world” (Unfinished Agenda). In another year he had committed his life to Christian ministry.

As a young Christian, Newbigin was nourished by the Student Christian Movement, an organization in the universities that then had an intensely evangelistic and missionary ethos. (After graduation he spent several years as an scm staff worker, as did his wife-to-be, Helen.) He took the Student Volunteer Movement’s pledge, “It is my purpose, if God permit, to become a foreign missionary.” The svm slogan, “The Evangelization of the World in This Generation,” still had currency.

In seminary, he studied under John Oman, a disciple of Schleiermacher and his program of accommodating the gospel to the “cultured despiser.” Yet an intense study of Romans over one vacation period convinced Newbigin of “the centrality and objectivity of the atonement accomplished on Calvary. … At the end of the exercise I was much more of an evangelical than a liberal” (Unfinished Agenda). He has never wavered from that orthodox understanding of the gospel.

The Bible, the Cross, the Atonement, the evangelization of the world: put them together and you have the makings of missionary fervor. It may seem some distance from this to Newbigin’s learned disquisitions on the epistemology of science or on the impact of Enlightenment thinking. Really it is not, for two reasons. One is that missionaries—especially pioneer missionaries—have often been keen explorers and analysts of the culture they enter, of its languages and customs, of the points at which it is most open (and most resistant) to the gospel. Newbigin certainly represents the type, both in India and in England.

The second reason is that Western thinking—the “acids of modernity”—have seeped everywhere around the world. Young people assume Western ways in Bangkok and Rio de Janeiro, in Jakarta and Banjul. A missionary cannot afford simply to understand traditional culture. He or she must comprehend modern urban, mass-media culture. “If one is looking at the total situation of Christianity in the contemporary world, addressing European culture is the most urgent question, and for two reasons: first because it is modern, post-Enlightenment Western culture that, in the guise of ‘modernization,’ is replacing more traditional cultures all over the world, and second because … this culture has a unique power to erode and neutralize the Christian faith” (Word in Season).

Like any real missionary, though, Newbigin’s fundamental concern is not to analyze the situation correctly. It is to raise up believing congregations. Thus the drumbeat of confession sounds in all his work. “How can this strange story of God made man, of a crucified savior, of resurrection and new creation become credible for those whose entire mental training has conditioned them to believe that the real world is the world that can be satisfactorily explained and managed without the hypothesis of God? I know of only one clue to the answering of that question, only one real hermeneutic of the gospel: congregations that believe it” (Word in Season).

Proper confidence in the gospelSelly Oak Colleges’ President Martin Conway remembers an occasion when a group of visiting Indian Christians learned that Lesslie Newbigin once lived at the colleges. “Where?” they asked, and when they were shown the modest home, immediately lined up in front of it to have their pictures taken.

That does not happen with many missionaries. Such a reputation comes not from intellectual brilliance, nor from missionary fervor. It is bred by character remembered with love. In India, Newbigin met regularly with pastors and other church leaders, teaching the Bible to them, praying with them, visiting in their homes.

In his postretirement career, Newbigin has had less opportunity to make such a personal impact. Most people encounter him through his books or through a lecture, and in either case, they are not likely to learn much about him personally. He is too much an old-fashioned English gentleman to share personal experiences with an audience. (Though he has lived the kind of intellectually rich life that might, in fact, lend itself to illuminating his analysis.)

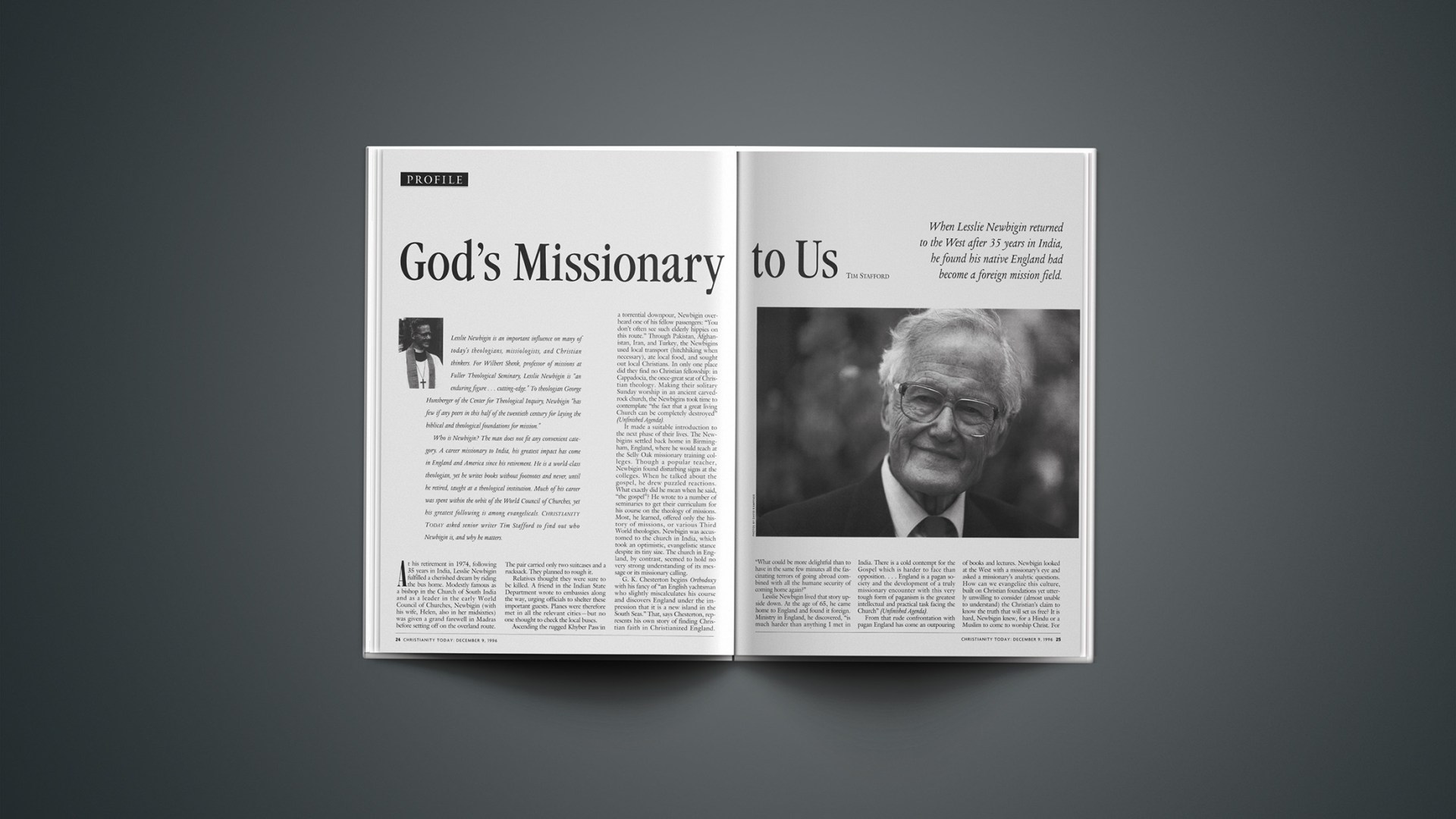

Today, at the age of 87, almost blind because of macular degeneration, Newbigin and his wife live in a group home for the elderly in London, occupying two very ordinary rooms. It is not the setting one expects for an influential bishop, yet he seems to find great pleasure in it. Showing the garden (which he has had to abandon caring for, because he cannot see the plants), Newbigin exclaims on his good fortune to have such a lovely place. He treats with gracious courtesy the others who share the house, though as one young friend, Jenny Taylor, points out, many of them cannot hear what he says, and he is too blind to detect when they cannot.

Retired now from parish ministry, he still keeps up an active schedule, lecturing and writing. Besides that, he makes a career of encouraging others, often younger people, usually in quiet, behind-the-scene ways. He does not act like a great man. In fact, it is not entirely clear that he realizes he is a great man. If he does, he does not seem to consider it important.

Newbigin’s first audience was among mostly liberal Christians, but in the past year he has lectured repeatedly at Holy Trinity Brompton, the Anglican church that is London headquarters for the charismatic Toronto Blessing. It seems an unlikely match, but he has come away with a deep thankfulness for what he has seen in that church. He has not spoken in tongues, he says, but (with a twinkle in his eye) he tells how he has learned to lift his hands in prayer.

So near the end of his life, this man, who has struggled for church unity all his adult life, emerges as one of the very few theological thinkers who can speak to all poles of Protestantism: the liberal, the evangelical, the charismatic. (He has the ear of many Catholics as well.)

He does this without sacrificing a bit of boldness. Newbigin says that he does not relish an argument, but over his lifetime he has launched himself into any number of desperate ones. Not everyone loves him, for he can use English to hit error like a hammer. Yet he behaves with such humility that even those who disagree must admire him.

“I have felt that my main ministry,” Newbigin says, “was just to encourage ministers and pastors and clergy to be more confident in preaching the gospel. What I have been so horrified by is a kind of timidity by Christian preachers and ministers. The kind of attitude that says, ‘Well, I happen to be a Christian, but of course I wouldn’t expect you to think that.’ ” Lesslie Newbigin is helping Western Christians to regain their missionary nerve, to preach the gospel not only to the ends of the earth, but also in those hostile climates closest to home.

Making the Gospel Public: Recent books by Lesslie Newbigin.

—The Open Secret: Sketches for a Missionary Theology (Eerdmans, 1978). A summary of Newbigin’s approach to Christian missions.

—The Other Side of 1984: Questions for the Churches (WCC Publications, 1983). The seminal book for the gospel and culture movement.

—Unfinished Agenda: An Autobiography (Eerdmans, 1986). An expansion of The Other Side of 1984, based on his 1984 Warfield Lectures at Princeton Theological Seminary. Newbigin outlines the main contours of modern culture, exploring the idea of the gospel as public truth and its implications for contemporary culture.

—The Gospel in a Pluralist Society (Eerdmans, 1991). A rejection of the idea that the gospel is merely a matter of private opinions or personal values. Newbigin reasserts the objective, historical truth of the gospel and argues that the public life of Western culture must be evaluated in its light.

—Proper Confidence: Faith, Doubt and Certainty in Christian Discipleship (Eerdmans, 1995). A continued attack on Enlightenment assumptions about knowledge and their impact upon the churches.

—Truth and Authority in Modernity (Trinity Press International, 1996). Appearing in the “Christian Mission and Modern Culture” series, this brief book asks how the church can speak with authority in a culture that is suspicious of all claims to authority.

By Lawrence Osborn, Cambridge, England, author of Restoring the Vision: The Gospel and Modern Culture (Mowbray, 1995).

Copyright © 1996 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.