The Sunflower: On the Possibilities and Limits of Forgiveness, by Simon Wiesenthal, with a symposium edited by Harry James Cargas and Bonny V. Fetterman. Revised and expanded edition (Schocken, 271 pp.; $24, hardcover, $TK, paper). Reviewed by L. Gregory Jones, dean of the Divinity School at Duke University and author of Embodying Forgiveness (Eerdmans).

The story is gripping, moving, yet harrowing: a dying Nazi confesses his complicity in mass murder to a Jew imprisoned in a concentration camp, and even asks the Jew for forgiveness. How should the Jew respond? How could he be expected to respond?

This might make for an ingenious piece of fiction; alas, it is a true story that happened to none other than Simon Wiesenthal, the remarkable man most noted for his work tracking down Nazi war criminals. He is also noted for The Sunflower, his account of an encounter in 1944 with Karl, a Nazi, and Karl’s deathbed confession.

The Sunflower begins with Wiesenthal, an educated Jew, as an inmate in a concentration camp in Poland. He is part of a work detail that is sent from the camp to do cleanup work in a makeshift hospital for wounded German soldiers, a building that had once been the school that Wiesenthal attended. Along the way, Wiesenthal notices a cemetery for deceased Germans; he notices that each grave has a sunflower on it. For Wiesenthal, the sunflower signifies many contrasts between the fate of the Nazi dead on the one hand, and his anticipated fate and those of Jews like him on the other: individual graves, decorated with sunflowers, versus mass graves, unmarked and unmarkable. Continual connections to the living world versus a loss of all such connection.

Upon arriving at the hospital, Wiesenthal is ordered by a nurse—indeed, a nun—to follow her into the building. He is taken down the hallways, and then brought into a room where he encounters a dying Nazi, a 21-year-old ss man named Karl. Karl’s body is wrapped in bandages, covering even his eyes and head, and he is barely able to speak. Yet before he dies he wants to confess a crime that has been “torturing” his memory, and more specifically, he wants to confess to a Jew. He wants to confess his shame at having become a Nazi.

Even more, he wants to confess a particular episode in which he killed a family trying to flee a building, crammed with hundreds of Jews, to which the Nazis had set fire. He cannot get that family’s faces out of his mind; he covers his blinded eyes as he retells the episode to Wiesenthal. He received his mortal wounds, he tells Wiesenthal, in a later battle in which he could not bring himself to shoot another group of Jews. As the faces of the family he had killed earlier filled his consciousness, a shell exploded by his side, causing his blindness and, eventually, his death.

As Wiesenthal listens to Karl’s story, he is simultaneously attracted to the authenticity of the confession and repelled by the horrifying tale Karl is telling. Wiesenthal’s thoughts continually return to those sunflowers, signifying the different worlds of dying Nazis and Jews. As Karl confesses, Wiesennthal does not leave, but neither does he speak. Wiesennthal has no doubts that Karl’s confession reflects “true repentance”; Karl indicates that he wants to die “in peace,” and that he has “longed to talk about [his crime] to a Jew and beg forgiveness from him.” Wiesennthal is moved by Karl’s repentance, yet he concludes that the contrast between the dying Nazi and the doomed Jew is too great; “between them there seemed to rest a sunflower. At last I made up my mind and without a word I left the room.”

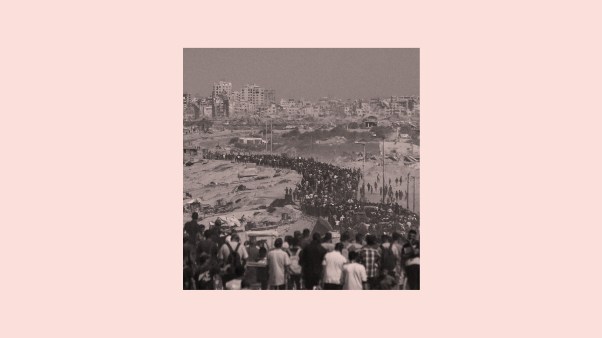

Begging for forgiveness: The dying Nazi wanted to confess his crime to a Jew and die “in peace.” Wiesenthal walked away in silence.

Yet Wiesenthal is troubled, indeed haunted, by questions about what he did or failed to do. When he returns to the camp, he asks his fellow inmates what they would have done. After the war ends, he takes the time to go to see Karl’s mother, wanting to find out from her more about Karl’s character. The mother’s words confirm Wiesenthal’s judgment about the truthfulness of Karl’s confession and the sincerity of his repentance. Yet Wiesenthal is also troubled by the lack of remorse shown by most of the Nazis who were brought to trial after the war. And so, at the end of the tale, Wiesenthal continues to wonder: “Ought I to have forgiven him?”

He notes that there are many kinds of silence, and he wonders whether his own silence perhaps was more eloquent than words might have been. He also indicates that “only the sufferer is qualified to make the decision” concerning forgiveness. Even so, while his own eloquent telling of the tale seems to suggest the impossibility of forgiveness and the significance of silence, he continues to wrestle with the question of forgiveness, struggling to find a way to tell the story that might offer hope that his future, and our future, might not be bound by the destructiveness of the past.

Finally, then, Wiesenthal addresses a question to the reader of his tale: “You, who have just read this sad and tragic episode in my life, can mentally change places with me and ask yourself the crucial question, ‘What would I have done?'”

What would you say in response? What could you say? After the original version of the book was published in 1969, Wiesenthal invited 32 people to reflect on the question “What would I have done?” Those reflections were included in a “Symposium” that composed the second half of a 1976 edition of the book. The symposium included novelists, theologians, lawyers, judges, and other intellectuals; Protestants, Catholics, and Jews as well as agnostics and atheists. There were some well-recognized names: Abraham Heschel, Primo Levi, Herbert Marcuse, Jacques Maritain, Martin Marty, Cynthia Ozick. There also were some provocative and moving contributions from less well-known writers, including Milton Konvitz and John Oesterreicher.

These reflections provided readers additional engagements with Wiesenthal’s story: deeper reflections, challenging questions, and pointed objections to anyone’s settled positions. Some said Wiesenthal should have forgiven Karl, and others thought he never should have; some interpreted his silence as a gesture toward forgiveness, and others thought it was a pointed refusal; some worried about the dangers of “cheap grace,” while others worried about the effects of a refusal to forgive.

In 1997, a new edition of The Sunflower was published, complete with a revised and expanded list of contributors to the symposium, and this edition is now available in paperback. Some of the additions are particularly significant, most notably a reflection from Albert Speer, a member of Hitler’s inner circle whose memoir Inside the Third Reich reflects a sense of repentance for his Nazi past. Other additions are less significant for the content of the reflections than for the writer’s stature in popular religious awareness: examples include Matthew Fox and Harold Kushner. Most notable, however, is the decision by the editors of the new edition to include reflections from people involved in other, more recent contexts of massive suffering and injustice: Sven Alkalaj, the ambassador of Bosnia and Herzegovina to the United States; the Dalai Lama; Dith Pran, the journalist whose wartime life and suffering at the hands of the Khmer Rouge was portrayed in the film The Killing Fields; and Harry Wu, imprisoned by the Chinese Communist government for 19 years in a labor camp.

The new edition reveals both the phenomenal, enduring power of the story itself and shifts in cultural and theological hopes and fears about the possibilities and limits of forgiveness in relation to massive evils and injustice.

What does this new edition tell us about how people’s thinking about the legacies of the Holocaust, and about forgiveness, has changed over the past few decades?

In part, there is a deeper despair, and even cynicism, about the possibilities of forgiveness given the recurring realities of horrifying evils around the world. After all, humanity has not seemed to learn any lessons from the Holocaust’s horrors. One needs only to mention the killing fields of Cambodia, shallow graves in Bosnia, brutal killings in Rwanda, or the cycles of violence and vengeance in the Middle East to wonder whether there is any hope for an end to unbearable, unspeakable human cruelty.

Some people simply give voice to that despair, indicating that we cannot afford even to think of forgiveness in the midst of such injustice. Yet this leads others to develop, or reinforce, a principled opposition to the appropriateness of forgiveness. World events of the last three decades seem only to have solidified judgments that forgiveness trivializes human suffering and gives license to unprincipled brutality and injustice.

Unsurprisingly, Christian contributors to the symposium, both in the 1976 edition and in this new one, seem more willing than others to speak of forgiveness. To be sure, there are risks here. After all, it was the Jews who were the victims of the Holocaust, and in many cases, the perpetrators (like Karl) or collaborators were people who had at least been raised as nominal Christians. To speak of forgiveness could be an offer of “cheap grace” that is deeply problematic for anyone, and especially for victims, to hear. Martin Marty’s contribution, found in both editions, is appropriately cautious about Christians offering either cheap grace or cheap advice to Jews and other victims of massive suffering. Even so, he offers important reflections, grounded in Christian worship of the God of Jesus Christ, on how signs of grace and forgiveness may offer hope for a future not bound by the destructiveness of the past.

Marty’s reflections may be offensive to Jews and others who have endured horrifying suffering. But they offer an important and, to my Christian mind, truthful gesture. It is perhaps a sign of the editors’ own despair that the most profoundly hopeful and moving Jewish reflection in the first edition, by Milton Konvitz, was excised from this new edition. Konvitz was appropriately worried about forgiveness, but his proposed words of compassion for Karl are remarkably poignant:

It seems to me, though I say this with diffidence and hesitation, that in this encounter the spirit of the Jewish tradition called upon the narrator to say to Karl: “I cannot speak for your victims. I cannot speak for the Jewish people. I cannot speak for God. But I am a man. I am a Jew. I am commanded, in my personal relations, to act with compassion. I have been taught that if I expect the Compassionate One to have compassion on me, I must act with compassion toward others. I can share with you, in this hour of your deep suffering, what I myself have been taught by my teachers: ‘Better is one hour of repentance in this world than the whole life of the world to come’ (Avot, IV, 17). ‘Great is repentance, for it renders asunder the decree imposed upon a man’ (Babylonian Talmud, Rosh Hashana, 17b). It is not in my power to render to you the help that could come only from your victims, or from the whole of the people of Israel, or from God. But insofar as you reach out to me, and insofar as I can separate myself from my fellow Jews, for whom I cannot speak, my broken heart pleads for your broken heart: Go in peace.”

Perhaps our culture’s, and even our world’s, cynicism needs the challenge of hope found in Marty’s and Konvitz’s reflections. We know all too well the horrors of the Holocaust, of Bosnia, of the Killing Fields, of apartheid in South Africa. But do we know as well the possibilities of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa? What might Tutu, or Mandela, or even de Klerk, say at this point about the possibilities of forgiveness in the wake of systematic injustice?

We cannot avoid the challenges, and we dare not trivialize suffering with cheap grace. At the same time, we ought not become numb to the possibilities being offered by the Spirit of God who, we are told in 2 Corinthians, is making all things new. Alas, particularly with the absence of Konvitz’s reflection, the new edition of The Sunflower seems to encourage numbness rather than hope.

Can we tell stories, and offer judgments, of compassion and forgiveness that shine personally without failing politically? Can we respond to hellish injustices in ways that offer hope for a new and renewed future? Some of us have staked our lives on following One whose life, death, and resurrection commits us to the conviction that we can. But we need a deeper engagement with the words of Micah 6 and Luke 24 to do so. Perhaps the next edition of The Sunflower’s Symposium can move our reflection in a more profound, and a more hopeful, direction.

Copyright © 1998 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.