As David Simpich begins his evening show, called Portraits, the atmosphere is one of edgy half-attention. Young men indulge in the boisterous and ironic laughter that lets a performer know they may be too cool for this show. Perhaps they expect a typical puppet show: the crude humor of Punch and Judy, or the maudlin comforts of the late Shari Lewis’s beloved Lamb Chop.

But Simpich works with marionettes—elaborately sculpted and jointed dolls that wear costumes rich in period detail. Using an intricate collection of strings, Simpich breathes new life into such characters as King David, Francis of Assisi, Abraham Lincoln, Pinocchio, Helen Keller, and John Merrick (the Elephant Man). When Simpich reaches the closing moments of his 70-minute show, several hundred students listen in a rich silence. He receives a lively ovation.

“There is a preconceived idea of marionettes and what they’re going to do,” Simpich tells Christianity Today the morning after his performance at Wheaton. “It’s exciting to me to have the marionettes overcome that.”

To enter the world of David Simpich is to step into a narrative spanning centuries. Many of his characters quickly gasp for breath between their sentences, conveying a greater urgency and pathos than an observer normally expects from puppets.

In addition to Portraits, Simpich takes on an array of challenging classical stories, including A Christmas Carol, Great Expectations, Pilgrim’s Progress, and The Little Mermaid. Watch Simpich working and you’ll see him at all times—he does not hide behind a curtain—and yet you may easily forget all these voices and personalities are coming from only one man. A Simpich performance is captivating because it is so intimate.

“The live experience of having the puppeteer really there, really giving the voice, will always be the most valuable, the truest form of puppetry,” Simpich says. “You know something can go wrong when you do it live, and things do, often. … But I would say that it is worth the difficulty, as opposed to just programming the whole thing where the human soul is not somewhere up there, giving, on the stage.”

From Dolls to Storytelling

As Simpich grew up in Colorado Springs, dolls were the family business. His parents launched Simpich Character Dolls in Colorado Springs in 1952. Simpich experimented with hand puppetry as he grew up, thinking that marionettes were too complicated to master.In time, though, he found that he appreciated the classical discipline and the full-bodied complexity of marionettes. By 1984, with the help of some library books, Simpich began creating marionettes. A year later, he developed Beauty and the Beast into a show.

Sophisticated puppetry appears as far back as 1573 in England and the 17th century in Japan. Two common theories prevail about the source of the word marionette. One theory says marionettes appeared in Nativity scenes in churches (the Middle French word maryonete means “little Mary”). The other theory ties the word to the Italian morio, for “buffoon” or “fool.” Neither marionettists nor other puppeteers are widespread in 21st-century America; Puppeteers of America has about 2,000 members.

Simpich now has 14 shows in his repertoire. Simpich travels often with his wife, Debby, and their four children as he performs an average of 150 shows in a year. The Simpiches use a homeschool curriculum so the family can stay together throughout the year.

The family packs 700 pounds of equipment into eight trunks and drives across the nation in a van. Touring is not lucrative—the family survives financially because the shows are only a part of the family business—but Simpich would like to tour more frequently.

Strings Are Good

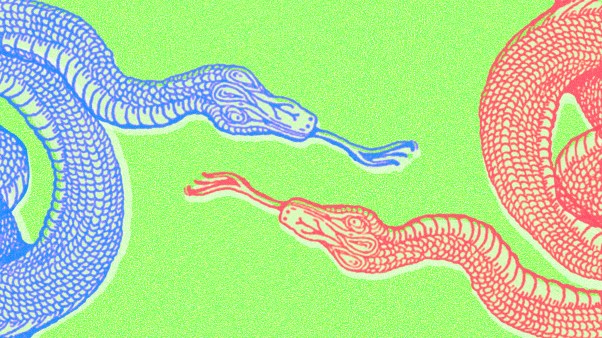

A common theme in Simpich Marionettes shows is of characters facing seemingly insurmountable challenges. In Portraits, characters meet those challenges by “remembering the strings”—realizing their lives are directed by a force much larger than themselves.He says of Francis, for instance:

“I have this simple nine-string character puppet telling me that simplicity is a good thing. It’s freedom. It’s connection. It’s being an extension of someone who knows what he is doing. I find that the complication of a lot of extra strings in my life—usually these complications don’t come from the One who is pulling the good strings. It comes from other forces that are attempting to strangle me.”

While his shows are not designed solely as vehicles for evangelism, Simpich says, his Christian faith has become inseparable from his work. “There was a time when my faith was there in my work, but it was safe enough that I could still go into public schools,” he says. “As Christian themes have emerged in my work, that has opened some doors and closed some others.”

Regardless of how often he is performing, or whatever the venue, Simpich is thankful to be part of a classical art form that has survived for more than four centuries. “It seems important that we keep something living in our entertainment—something that’s really happening and is not just manipulation,” Simpich says. “A lot of children don’t see live theater, and even a lot of adults have only a limited exposure to it.”

Douglas LeBlanc edits The CT Review.

Copyright © 2001 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

For more information, see the home sites for David Simpich Marionettes and Simpich Character Dolls. Simpich talks more about his craft in an interview on his site.

Puppeteers of America, a national nonprofit organization founded in 1937, provides information, encourages performances, and builds a community of people who love puppet theatre.